“Without contraries there is no Progression”

William Blake

Index:

- » SUMMER MESSAGE by Sophie Bassouls-Daniélou

- » SHE OF THE THOUSAND FACES: PHOTOGRAPHY AND THE REPRESENTATION OF INDIAN WOMANHOOD IN THE WEST by Parvati Nair

- » A TESTIMONY ON THE EROTIC SIDE OF DIVINE “BLISS” by Alain Daniélou

- » RETELLING INDIAN EPICS by Samhita Arni

- » RECORDING WITHOUT END by Peter Pannke

- » WAYS OF ENGAGING – COMPELLING IMAGES BY DANIÉLOU & BURNIER by Malavika Karlekar

- » PARALLEL CINEMA IN INDIA by Himadri Ketu

- » A LETTER FROM… ITALY by Madhu Kapparath

- » A LETTER FROM… SHANTINIKETAN by José Paz

- » 2015 ALAIN DANIÉLOU GRANT PROGRAMME by Anne Prunet

- » The Alain Daniélou Foundation’s UPCOMING EVENTS 2014

- » The Alain Daniélou Foundation’s PROPOSALS 2014

SUMMER MESSAGE by Sophie Bassouls-Daniélou

Sophie Bassouls-Daniélou is a photographer and President of the Alain Daniélou Foundation’s Honorary Board

Dear Members of the Honorary Board, Dear Friends of the Alain Daniélou Foundation,

We share a detestation of obligatory formalities and academic duties. Don’t worry : this message is both short and spontaneous.

A year has already gone by since our delightful Mela in Rome and at Zagarolo, marking the birth of the Alain Daniélou Foundation, facilitating our meetings.

Celebrating anniversaries could easily become monotonous, but with this – our first – there’s no risk, since it doesn’t yet belong to the sphere of habit.

Without attempting to take stock of the Alain Daniélou Foundation’s activities, I am pleased to see that the impetus given is a lasting one, without any lessening of enthusiasm.

As a metaphor I am sending the picture of this tree: at a glance it says more about the determination, perseverance, energy and deep-rootedness of our Foundation than several paragraphs of text.

It says nothing about exchanges between artists from different cultural backgrounds or disciplines – one of the Alain Daniélou Foundation’s major aims – except that in our imagination we can hear the birds in its branches whose song reaches every point in the forest. Music and dance without borders.

Happily setting aside the factor of mischance, those working for the Alain Daniélou Foundation are plunged in innovation and the pleasure of creating.

Sincerely,

SHE OF THE THOUSAND FACES: PHOTOGRAPHY AND THE REPRESENTATION OF INDIAN WOMANHOOD IN THE WEST by Parvati Nair

Parvati Nair is Director of the United Nations University Institute on Globalization, Culture and Mobility (UNU-GCM)

This text was presented as one of the contributions to the fourth section of “The Body Conference”, which took place at The Labyrinth on June 23-24, 2013. The subject of the section was the influence of India on the West, and Parvati Nair focused her contribution on the relevance of photography as a means of rescuing the complexity of Indian womanhood beyond the entanglements of traditional (Indian and Western) representational models.

Firstly, my sincere thanks to the organizers of the Alain Daniélou Foundation for this very kind invitation to be here at this conference on the Body. I come, not as an expert on Indian culture, but as someone working in the field of Cultural and Migration Studies and who writes on photography, who is also, by chance, a second generation Indian. As such, and growing up in a family, as I did, which was both always on the move and predominantly masculine, the question of Indian womanhood has long preoccupied me. To confront this question, however, has also been to enter into the entanglements of self, body, gender, nation and identity. Moreover, the markers of identity that I found before me were worthy of analysis because of their multiplicities. With my mother as the sole model who was physically present in my intimate surroundings, the narratives, the myths and the images of Indian women that I encountered via the press, mass culture, literature and images became inordinately important in terms of attempting this construction of more collective and gendered identity that I could, perhaps, grow into or adopt as my own. To quote Alasdair MacIntyre from his After Virtue (1981:205-206), ‘the story of my life is always embedded in the story of those communities from which I derive my identity. I am born with a past, and to try to cut myself off from that past, in the individualist mode, is to deform my present relationships… What I am, therefore, is a key part of what I inherit, a specific past that is to some degree in my present.’ The question that I pursued, that I still continue to pursue, is how exactly to name in lived or bodily terms that inheritance of gender and nation that is supposedly mine.

There was, I began to see, a divergence between, on the one hand, the evident contradictions that surfaced in terms of attempting to articulate the plural and entirely contingent facets of sex, gender and nation in a single bodily frame and, on the other, the drive both in the West and among Indians, to superimpose a set of traditional values and moral attitudes on Indian women that somehow simultaneously epitomized a stereotype of identity. To begin with, and as any Indian girl with a name such as mine might quickly become aware, the female icons of the Hindu religious pantheon have not only numerous arms, but also names and attributes. In the case of my Goddess, she swung from sensuous to fierce, the perfect consort and a force to reckon with. On a more material realm, the almost forced marriages of several female relatives and the overriding evidence of patriarchy that was hard to ignore during occasional visits to India clashed with the unchallenged political dominance of India’s rather overpowering former prime minister, Indira Gandhi. Meanwhile, on screen, in films such as Mother India (1957, dir. Mehboob Khan), both nation and the female gender appeared either long-suffering, condemned by fate to poverty and melodramatically self-sacrificial or else as bodies to be desired, objectified and devoid themselves of desire or agency. On a more domestic front, I struggled to locate my own position somewhere between India and the West and turned therefore to a set of family albums in order to trace my roots. The photographic journey took me back to the early 20th century and to the incursions of occasional photography in Keralan society at the turn of the century. What I found in these albums were images of great-aunts and great-grandmothers, in the tropical settings of Malabar or Travancore, some bare-breasted still and framed within the kinship matrilineal structures of the Nair clan, the as yet tentative modernity of their surroundings ensconcing them in a spatiotemporal framework of apparent simplicity, far removed from the chaos and the choices of the present.

Photographs, imbued as they are with pathos and mystery despite depicting reality, offer a three-dimensional frame within which to pursue the ideas of body, gender and nation across time and space. In so doing, they launch the imagination into journeys of exploration and help create a mental archive of imaginations of the body as a field of multiple and multi-dimensional configurations of emergent histories. This is so as much in the context of India as anywhere else. At stake is the quest for identity, and the positioning of the self as a politicized agent, where what matters is not so much the goal of reaching any conclusions as the pursuit itself. And it is through this pursuit that a dynamics of imagination is put into force, whereby rethinking certainties and revising perceptions and perspectives may begin. In what follows, I shall attempt to trace the changing contours of the female Indian body through reference to the works of a few selected photographers, so as to indicate, althought in a limited way, the infinite possibilities for reimagining the body, and with it, questions of sex, gender, nation and identity, that come to us via photography.

Photography, both documentary and vernacular, has long acted as a window onto other times and places. A contradictory medium, it gestures to the past and, at the same time, interjects in the present, casting ambivalence on the here and now through temporal and spatial disruption. In so doing , it instills on the viewer what Marianne Hirsch refers to in her Family Albums: Photography, Narrative and Postmemory (1997) as ‘postmemory’. For Hirsch, postmemory is belated, secondary and a prerogative of the displaced, a means whereby collective memory provides routes to constructing personal memory, and hence narratives of identity. As traces of memory, photographs are prime ‘texts’ of postmemory, fragments of the past that cast shadows on the present. They are more after-images than images, for they serve not merely to represent or depict a place and a time, but also as tropes of imagined memories, allowing for orientation in the face of displacement and rupture. At the same time, an inherent contradiction lies at the core of this medium: for still photography is a fluid medium, able to cross contexts and to offer perspectives that are often based as much on the viewer’s historical mode of seeing as on what is in the frame. As John Berger has rightly pointed out in his seminal Ways of Seeing (1972), how we see is determined by our historical conditioning. How we see images of the bodies of women, then, is framed by the many historical discourses that inflect and direct our vision, frames that are at once intrinsically linked to our own collective legacies of imperialism, colonization, patriarchy and heteronormativity, not to mention the overriding effects of colonialism and the market economy on how we regard gender, sex and nation.

Perhaps it is important at this juncture to recall that photography is not so much a means of representation as it is a means of changing perceptions. Photographs bring new insights and new perspectives to the eyes of viewers. In the context of postcolonial nations, such as India, the study and the archiving of photography have yet to be fully undertaken. Yet, to examine images from the colonial period, for example, is to glimpse hidden histories, to reconsider the past in terms, not so much of grand, unbroken historical narratives, as of embodiment and lived experiences, always in the plural. In turn, this leads to a re-envisioning of the past and, thereby, to a repositioning of the self, be this individual or collective, in time. As Zahid Chaufhary states in his Afterimage of Empire (2012), ‘I read the phenomenology of photography as the phenomenology of sense perception.’ (2012:25). He goes on to state that ‘the camera… gives us the capacity to see differently, to extend our sight into heretofore unknown spaces, to note the presence of objects in a way unseen before… the camera radically changes the terms of visibility itself because of the persuasive power of images.’ (2012: 26). By the same token, photographs alter the moment, cutting into the present with the imperative to re-envision. This is evident in collections such as Visualizing Indian Women: 1875-1947 (OUP, 2006), edited by Malavika Karlekar. Through images that run to the time of Independence, Karlekar creates a visual history of Indian womanhood, seen here in terms of agency, political participation and, most importantly, physical presence. While the commonalities of sex and gender bring the women seen here together, their photographs also posit their bodies as beings in time and place. They do so against a tacit backdrop whereby the photography of India, be it by Indians or non-Indians, has largely made no conscious effort to put the individuality of women in the frame, almost always depicting them, instead, as yoked to family, marriage and motherhood.

Nevertheless, and although yet to be properly acknowledged, it is important to note that photography, with its drive to force new vision, has worked against such obscurity. In Europe, the circulation of photographs by Raymond Burnier, not of living bodies, prone to the vagaries of time, but of those immortalized in the sculptures of medieval India, present in no uncertain terms the agency of the feminine, sexualized and fleshly despite being carved in stone. The image of the female Indian body seen in Burnier’s photographs conflates the divine and the sexual, binding the body thereby to the spirit as a universal force. Larger and more enduring than life, these images of the Indian woman persist in the Western imaginary as the backdrop against which to measure and map the female Indian body. The photographs also speak eloquently to those other cultural icons of infinite India that circulate in the West, the Kama Sutra and the bodily expressions of classical Indian dance, drawn from Hindu mythology and developed over centuries by devad?s?s, who honed the art of mixing religious and sexual expression through the body. In such a frame, gender and nation become infused, turning the body of the Indian woman into a topography of endless desire. A sexual force ensues, fuelled by the imagination, that turns these photographs into testaments of feminine potential. Burnier’s images are iconic, precisely because, by representing photographically these age-old representations in sculpture of Indian womanhood and of the human body as location of desire, they shed a double light on the role of visual media in triggering imaginations of historicized identity. To photograph is to sculpt with light. Burnier’s images amount, therefore, to the creation of sculpture from sculpture, releasing the sexual force of the original carvings from their spatial moorings into the fluid dynamics of photography with its potential for global travel. In pre-and post-war Europe, these images were instrumental in constructing an imaginary of the female Indian body that was both forceful, on the one hand, and fetishized, on the other, as a location of desire.

Today, the image of the Indian woman still struggles to overcome being framed by pre-existing narratives. While Indian women seek to break free from the shackles of patriarchy, orientalism and gender normativity, violence and the abuse of women is a daily fact of Indian society. The female Indian body took on a dark and terribly disturbing light at the end of 2012. It became both the preoccupation of millions worldwide and a topography of horror. The unimaginably brutal rape and subsequent death of a student in Delhi brought to the fore, as never before, the configurations of body, sex, gender and nation. In a scheme marked by extreme sexual violence, it was notable that the fragmented body of the woman in question quickly became a space for the emergence of discourses prevalent in the mass media that turned her trauma into a heroic or noble experience. The response of the media and the and the public who assumed this rape as a national event, despite the ongoing rapes that continued to occur, even as the public poured onto the streets, were a further instance whereby the body of the woman in question became the prerogative of the prerogative of the collective, not the individual. It became a forum for debating sexual violence and national failings, evidence of a more general assumption: namely, that the body of the Indian woman seldom belongs to her. From birth onwards, it is a public space, of propriety of the group possession, one over which she herself, as a female, may have little power to determine. This, of course, is not symptomatic of India alone, as it is indeed the source of many women’s struggles. The tendency to render the Delhi rape victim noble, in the impossibility of coming to terms with the unspeakable acts that had ripped her apart, is symptomatic of a more global trend to confer on women the binary locations of good or bad, virtuous or loose, wife or whore. Either way, their individual worth is lost in the larger collective concerns. Trapped in such binary constructions, many women find themselves unrecognized, their bodily existence, their voices and their histories obfuscated by the imposition of preconceived categories. The Delhi rape case of 2012 is symptomatic of a much wider phenomenon of violence against the bodies of women in India, since rape and domestic abuse are in fact daily occurrences all over the country. More importantly, and in direct contrast to the sexual agency of the female bodies carved in stone in medieval times, these binary constructions imprison female agency within a hetero-normative and often severely patriarchal scheme, silencing the sexual and turning the woman’s body into a fertile field for the savage rampaging of an often perverted male desire.

Again, photography can intervene to loosen such strictures. In his collections of photographs entitled Moksha (2005) and Ladli (2007), the US-born photographer Fazal Illahi Sheikh offers numerous photographs of Indian women. By using the portrait as his principle medium, Sheikh traces the lives of women, born disempowered within cultural mores that confine them, so that they become subject to violence, poverty, degradation, alienation or, quite simply, the vagaries of fate. Sheikh’s portraits focus very carefully on aspects of the woman’s body, her skin, her eyes, her hands, the dust in her hair. Photography is akin to skin in its ability to brush the surface of reality. The alienation of women, a condition that affects the historical course of millions in India and accompanies them from birth to death, rises from its buried, disavowed and silenced depths to the surface of each and every image. In so doing, and though the light and shade that falls on the bodies of Indian women, always depicted in his work in the plural, Sheikh offers us not so much a portrait of Indian womanhood as a deep indictment of Indian civil society. Sheikh’s work comes with an altruism that includes the free circulation of his images, without consideration for the marketing aspects of copyright. The disregard for standard economic protection related to artwork is important to note. It cannot be dissociated from that other fervent economic market, whereby the bodies of women become subjects of sexual ownership through the dowry system that relegates them to marriage, motherhood and objectification. In a tacit way, Sheikh flings into the air and casts aside the usual, and often unquestioned, normativity whereby images and, in this case, female subjects are privy to the dictates of established structures, such as those of gender hierarchies, the dictates of the marketplace, laws and practices of control, and, ultimately, the very intimate connections between, on the one hand, the nation-state and profit and, on the other, the nation-state and patriarchy.

For those who follow questions of sex, gender and identity through photography from or on India, Sheikh’s images did not come without the backdrop of a profound questioning of sexual and gender presumptions via the medium of photography. Ever since the publication in 2001 of Dayanita Singh’s photo-essay on the eunuch Mona Ahmed, entitled Myself, Mona Ahmed, photography has served to question and even subvert established notions of sex, gender and identity. Born male and living life as a female, Mona Ahmed suffers a double exile, first from the family of birth and then from the community of hijras to whom she belonged. Furthermore, she suffers the forced removal of an adopted child, whereby she is deprived of the myth of motherhood that had for a time bestowed sense to her fractured life. Having abandoned a series of sex-change operations mid-way, she remains in the blurred border zones of male and female, neither one nor the other, her body a space of indescribable longing. Singh’s brave essay overrides the habitual divisions between hij??s and mainstream society, revealing them to be both intimately connected and lacking articulation. Further, her images trace the shape of desire, in all its highs and lows, as a sexual force that runs through the body, be this masculine of feminine or, indeed, neither. For Mona Ahmed’s indeterminate body, hovering in the interstitial sexual spaces between masculine and feminine, is a third space, one from which, as Homi Bhabha noted as long ago as in 1994 in his Location of Culture, is a dialectical space for rethinking the horizons of the imaginary with regard to the body, sex, gender and nation. Photography, too, is a third space, an aestheticised sculpture of light that hovers in the borderlines between reality and representation. From this ambivalent location, ambiguities ensue, and with them, questions. This is the political prerogative of photography: to trigger questioning and to release preconceptions, prejudices, presumptions, from their ideological moorings. Most importantly, the body of Mona Ahmed, as seen here, is deeply human, throbbing and alive despite her ultimate self-imposed exile to a graveyard. Singh portrays her in terms of her pain, so that her body becomes a nerval junction where the ideologies of nation, sex and gender cruelly collide. Ironically, it is through such pain and through the language of longing that she achieves her dream of coinciding with the bodily and lived realities of many Indian women, who also live their lives in overriding contexts of patriarchy in terms of pain and longing.

Less than a year after the untimely loss of one of India’s most indisputably important photographers of women, Prabuddha Das Gupta, it seems apt to end this paper with a consideration of what his photographs have brought to bear on conceptions of the female Indian body – if such a thing exists. As someone who categorized himself as a fashion and art photographer, rather than as a documentarian, Das Gupta inevitably chose urban women as his subjects. Many are prominent figures in the world of fashion, film or media. Through the often very stylish filter of black and white, his Indian women are seen in dire contrast to the subjects of, for example, Fazal Sheikh. At ease in their bodies, often beautiful or elegant, Das Gupta’s subjects rise above the confines of nation to slot often into indeterminacies of sexual preference and gender politics that make them synonymous with well-heeled global subjects anywhere in the world. They are a class apart from the gritty and gutted likes of Mona Ahmed. Das Gupta’s lens is selective. However, precisely through the almost pristine elegance of black and white, his images enter into dialogue with the question of how Indian women are seen, of what Indian women may seek, and of what may be within their reach, proposing photography as a means to revising history. In this sense, his work is important. As a fashion photographer, much focus lies, of course, on the body of Indian women. Through his nudes and semi-nudes, which trace the body as a site for the self, he proposes a different equation from what tradition, patriarchy and supposed Indian ‘values’ have long imposed through subsuming the agency of women into patriarchal agendas. By uncovering the body, he uncovers also both potential and agency. His photographs release the image of the Indian woman into a different sphere, one where the subjects and their viewers become free to make choices and to reinvent themselves, although always apparently within the supportive zones of capitalist comfort, of which, indeed, his fashion images were part and parcel of. This may be troubling, and indeed an aspect of the globalized, shining India that continues to elude the masses, but it is also a counterpart to reality, a suggestion of reality lived otherwise, on the wing of what, at the very least, appears as one’s own terms. Many questions ensue from Das Gupta’s photographs, questions around agency, capital, photography as merchandise, glorification and the distancing of representation from reality. Even so, his work is important, not only for its inherent visual grace, but also because he, for one, frames the female body in terms of both ease and potential.

Photographic attempts to frame the female Indian body revert inevitably into questions of how to begin even visualizing such a concept. As ever with photography, multiple and often contradictory perspectives unfold. Always elusive, a photographic exploration of the body of the Indian woman leads not so much to a sexual knowing or to any kind of certainty, as to a conceptual un-knowing, to dissolving the preconceptions of imperialist, patriarchal or orientalist vision that frame the notions of sex, gender and nation as solid, bounded entities. Indeed, the body itself appears as in flux, changeable, contingent upon time and space, a space for questioning and not knowing.

References

» Mona Ahmed and Dayanita Singh, Myself: Mona Ahmed, Zurich: Scalo Publishers, 2001.

» John Berger, Ways of Seeing, London: Penguin Books, 1990.

» Homi Bhabha, Location of Culture, London: Routledge, 1994.

» Zahid Choudhary, Afterimage of Empire, Durham, North Carolina and London: Duke University Press, 2012.

» Alain Daniélou, L’Erotisme Divinisé : Les Photographies de Raymond Burnier, Paris: Editions Buchet/Chastel, 1962.

» Malavika Karlekar, Visualizing Indian Women: 1875-1947, Oxford: oxford University Press, 2006.

» Marianne Hirsch, Family Albums: Photography, Postmemory, History, Createspace Independent Publishing Platform, 2012.

» Mother India (film, 1957, dir. Mehboob Khan).

» Fazal Sheikh, Fazal Sheikh, Madrid: Fundación MAPFRE, 2009.

A TESTIMONY ON THE EROTIC SIDE OF DIVINE “BLISS” by Alain Daniélou

Introduction and translation: Adrián Navigante, the Alain Daniélou Foundation’s Intellectual Dialogue

Introduction: Daniélou at the “Musée égoïste”

The article reprinted below was written by Alain Daniélou on January 10, 1986 for a special column of the French newspaper Le Nouvel Observateur called “Le musée égoïste”. This newspaper section had the purpose of inviting some prominent personalities to comment on a work of art of their choice. Unlike the “public” museum, the “egotistic” variant was centered on individual experience and particular judgments of taste. The work of art to be presented was the result of a choice related to the singular story of the author being invited to write for the newspaper column. This does not mean that the subject was limited to the boundaries of private taste, quite the contrary: the very prestige of the authors assured the universal quality of the testimonies printed in the newspaper column. In other words: the “egotistic” modality combined the sensible nature of aesthetic reception with the category of pure pleasure –something that goes far beyond subjective arbitrariness and becomes an organ of living culture. Alain Daniélou, at that time 79 years old, decided to write a concise text related to the publication of the book Visages de l’Inde médiévale (Paris, 1985). This volume consists of an essay written by Daniélou on Indian arts and their relationship to different aspects of the Hindu religion and 76 impressive photographs taken by Raymond Burnier at different mediaeval temples showing a side of Hindu aesthetics that until then was not only unknown to most of the public but also considered decadent by Indian historians of art. From this ample variety of images, Daniélou chose – as iconographical motive for his newspaper article – a sculpture representing maithuna, which is part of his collection of Medieval sculptures.

Even if this Sanskrit word is to be understood primarily in the context of Tantric ritual as one of the pañcamak?ra (the five “m’s”: m??sa: flesh, matsya: fish, mudr?: parched or fried grain, madya: wine and maithuna: sexual union), Daniélou refers in this case to a much ampler semantic layer of this term. In fact, maithuna differs from the other elements of Tantric ritual inasmuch as it is no substance (like “flesh”, “fish”, “grain” and “wine”) but an act, and this act has to do with transgression. Viewed from the point of view of ritual, sexual union can be seen as an offering to the gods: two mortal individuals transform themselves by means of a performative sacrifice of their own mortality (precisely the contrary to the sexual function as reproduction and perpetuation of biological species). It is precisely because of the modality of this sacrifice that they go beyond their own limits and thus “communicate” with the sphere of the divine. From a symbolic point of view, the act contains much more than a transgression of conventional and ultimately mortal limitations: it is in fact the reproduction of something taking place on the divine plane, an erotic intensity at a cosmic level that is very often denied by convention, moral rules or simply a misunderstanding of the nature and the dynamics of what is called “creation”. In a short essay on Hindu erotic sculpture, Daniélou writes the following: “According to Tantric Shivaism, it is only when love and pleasure are accepted as a divine gift and as participation in the divine bliss that the living being reintegrates itself in the work of the Creator” (Alain Daniélou, Yoga, Kâma. Le corps est un temple, Paris 2005, p. 153). At the same time the intensity of the union and the symbolic aspect of transgression should not be understood in the sense of a destructive expenditure – as for example in the writings of the French thinker Georges Bataille. According to Daniélou, eroticism in the arts, in the field of religion and also in human experience has to do with measure, proportion and an expanded perception of cosmic correspondences: “One should also learn to contain and redirect the energy developed and expanded by means of eroticism with the aim of achieving inner realizations, one should be able to guide this sense of bliss that in sexual orgasm lasts but one instant in the direction of a mode of realization implying the liberation from the limits of individual existence and thus the experience of permanent bliss or divine union” (Alain Daniélou, Approche de l’hindouisme, Paris 2007, pp. 112-113). In translating the term ?nanda into “voluptuousness”, Daniélou does not deny the blissful aspect of the divine within the religious Weltanschauung of the Hindus, but he contributes to a better understanding of it. In revealing one side of divine bliss that mainstream religions to a great extent try to suppress, he shows that the only way to inner realization is by way of integration. It is perhaps in this sense that his testimony for Le Nouvel Observateur, dating back to the 1980s, has still today an undeniable validity and puts forward a task for future generations.

Text

Alain Daniélou: Arts, DNA and voluptuousness

Painter, musician, Sanskrit scholar and philosopher, Alain Daniélou lived in India for more than twenty years. At the beginning he worked with Rabindanath Tagore, and afterward he resided in Benares. After his return to Europe he founded the “International Institute for Comparative Music Studies” and published many books on Indian civilization, history, society, music, architecture and sculpture. His most important achievement was the rediscovery of Shivaism, the religion of the Indian pre-aryan civilization, and the theories about the nature of the world related to numerical factors. These theories also find their application in the cycles determining the evolution of civilizations and the destiny of human beings as well as in the aesthetics of proportions and musical semantics. His most recent book, “Visages de l’Inde médiévale” (Hermann, 166 pages, with 76 photographs by Raymond Burnier) presents the mythologies of the Indian pantheon, the rites, geniuses and goddesses presiding over the construction of temples, and it explains at the same time the connection between voluptuousness and mysticism.

Maithuna: photography by Raymond Burnier

Maithuna: This sculpture shown above dates back to the X century and originates from the region of Khajuraho. It is one of the most singular exponents of this style and this region to be found in Europe today. From the IX to the XII century, Khajuraho was the capital of the kingdom of Chandela, a Rajput dynasty of princes who fought with admirable courage against the Muslim invaders. It was an important cultural and religious center – toward the X century more than two thousand devadasis (sacred dancers) lived there allocated to the different temples. Are we going to see them again in Paris on March 12 in the frame of the prestigious exhibition taking place at the Grand-Palais under the title “The New Faces of Indian Arts”?

There are no barriers between love, artistic expression and wisdom. The ultimate criterion of the artist, the mystic and the lover has always been voluptuousness. It is in the most extreme moments of pleasure that we approach the divine. In the world of my childhood, every form of eroticism was regarded as something low and shameful, something to be rather hidden than shown. The discovery I made of the Khajuraho temples in the jungle of central India was something really intoxicating. My friend Raymond Burnier and I spent entire weeks locating, admiring, cleaning and photographing the innumerable and sublime images of nymphs and gods sculptured with unequalled style in their most ingenious coupling scenes and their most unexpected love phantasies, all of them depicted with a kind of insolent innocence. Back in those days nobody visited these temples, which were lost in the middle of the forest and therefore literally inaccessible to the human eye. The enigmatic and charming smiles of the goddesses was a fair response to the heartfelt connivance with which we observed their love-making scenes and by means of which we made them come alive once again. These goddesses never granted anybody such a warm smile as the one they granted to the ones who dragged them out of their millenary oblivion.

The art of the Indian sculptor is almost unique because of the balance he is able to achieve between stylization and realism. The Hindu craftsman carves a magical diagram on the stone, and with this gesture he produces deities hitherto hidden behind the stone. He catches them in the most unexpected moments of intimacy.

It seems to me that the mysterious diagrams configuring the proportions of these sculptures and permitting the works of art to achieve their stunning beauty have a certain correspondence – at an unconscious level – with the strange formulae that constitute our DNA, that is, the secret principle of our being. Each work of art, whatever its formal or abstract style, is ultimately based on a harmonic structure, a play of relations and numbers expressed in terms of colors, sounds, forms, and rendered perceptible by means of music, painting and architecture. It is this harmonic substratum and its relation to a cyphered code that constitute our nature and determine our sense of beauty, i. e. what we perceive through the mirror of the arts. Beauty is a bird to a bird, a serpent to a serpent. We explore the divine realm from which we descended within the mirror of the beauty of the other. The intensity of the pleasure we receive is perhaps the parameter to measure our success in life.

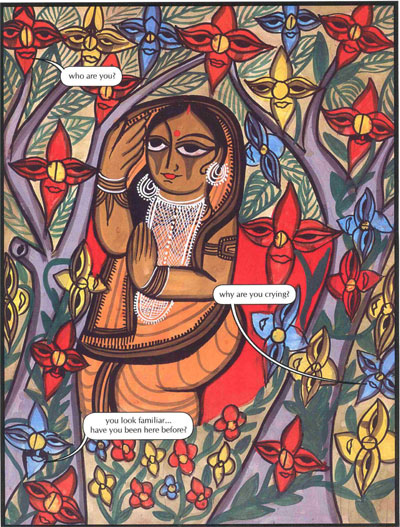

RETELLING INDIAN EPICS by Samhita Arni

Samhita Arni is a writer and screenplayer www.samarni.com

As a child who accompanied a diplomat father on various overseas postings – Indonesia, Pakistan and Thailand – the one constant in all the cultures I spent my childhood years in was the Ramayana. In Indonesia, a largely Muslim country, we watched the ‘Wayang kulit’, the shadow puppet Ramayana. In Pakistan, I was told as a five-year-old, that “Lahore’ came from Lavapuri – from a legend that claimed that Lahore was founded by Ram’s son Lava. In Chennai, my birthplace and the city my mother comes from, stories are still told of the founder of the Dravidar movement, E. V. Ramasami Naiker, Periyaar, who wrote a banned version of the Ramayana casting Ravana as a tragic hero, and – in an inversion of what happens at Dusshera – gathered hordes on the beach to burn images of Ram. In Thailand, one finds the Ramayana in many places – in the names of its kings, in Ayutthaya (from Ayodhya), and in a beautiful poem inscribed on the walls of a Wat, in which Ravana declares his undying love for Sita. Further afield, traces of the Ramayana still linger – in Angkor Wat in Buddhist Cambodia and Laos – like Lahore, also supposedly named after Lava.

And yet the Ramayana that is in ascendence today in the popular imagination – the Ramayana that was repeated to me by my Hindu family – was stripped of all these delightful cadences and associations that I could relate to. From a story inhabited with magic, sorcerers, demons, talking animals and flying monkeys, it shrunk to a hagiography, a story about an ideal man/God, and his ideal wife. This version perpetuated the notion of the Ramayana as exclusive Hindu property, and ignores the fact that the Ramayana has been retold – and is still being retold – by Muslims, Buddhists, Jains and people of other faiths. It was a story that prescribed roles for men and women, and told in such a way that it failed to grasp my imagination as a child. What could a girl – encouraged to think and question, to want and aspire to more than her mother and grandmother had ever had – admire in the silent, suffering, self-sacrificing Sita of popular imagination?

Five years ago, I re-discovered the Ramayana. I returned to India after almost a decade abroad, and I found a country where the Ramayana is still frequently referred to. Recently the supreme court mentioned the Lakshman-Rekha in the 2G case, and the term Ram Rajya made a frequent appearance in a school debate which I recently judged. A reality show on a Kannada channel, named a line that participants could not cross (the Lakshman-Rekha.) Moreover, the Ramayana was (and still is) part of a discussion about Indian identity and the state. And when I delved back into the Ramayana as an adult, I was surprised by what I found.

Just to speak of Sita, I was astonished to discover that, in one version, Janaka found Sita, as a child, playing with Shiva’s bow, and watched her lift it. Hence, he devised the test for her Swayamvara, for if Sita could lift the bow as a child, then the man who would marry her should at least be able to string the bow.

This Sita was physically strong.

Reading Arshia Sattar’s masterful translation of Valmiki’s Ramayana, I discovered that Valmiki’s Sita is one who says that Dharma is sukusma – subtle, intangible. This Sita advises Ram, in the forest, to give up his weapons for the duration of exile and live a lifestyle in keeping with the peaceful, non-material dharma of the forest and Vanaprastha.

This Sita was wise.

I became fascinated by the Ramayana and the many ways in which it was retold. This fascination has led to two books: The Missing Queen, a speculative fiction thriller published by Penguin and Zubaan, and Sita’s Ramayana, a graphic novel that develops a unique and compelling retelling by Patua Artist Moyna Chitrakar.

In the process of working to create a text to accompany Moyna’s fabulous artwork in Sita’s Ramayana, I explored the folk traditions, where women, singing in Sita’s voice, voiced their own problems in their descriptions of her suffering. In her voice, they express their own lives. The Missing Queen was inspired by many questions: What is the Ramayana? Is it a tale of love found and lost, of separation, or a narrative of war and empire? Is it an epic that prescribes roles for men and women, that describes the character of an ideal King and the ideal state that he rules over? But in this ideal state – how can one ever justify Suraphanakha’s mutilation, or Valin’s murder? In trying to explore these questions, I drew upon the multiple retellings of the Ramayana, to explore the differences in versions and perspectives – and to provoke the reader to ask questions about the epic (if they hadn’t before). In doing so – I hoped that the reader would question the primacy of the version of the epic we are most familiar with — and thus also query the narrative of modern India as it is told to us today by the media and our politicicans.

The Ramayana has been re-told, re-cast many, many times. This polymorphic tradition is precisely what A. K. Ramanujan’s essay explores. Here is Ramanujan’s account of my favorite anecdotes:

“To some extent all later Ramayanas play on the knowledge of previous tellings: they are meta-Ramayanas. I cannot resist repeating my favorite example. In several of the later Ramayanas (such as the Adhyatma Ramayana, 16th C.), when Rama is exiled, he does not want Sita to go with him into the forest. Sita argues with him. At first she uses the usual arguments: she is his wife, she should share his sufferings, exile herself in his exile, and so on. When he still resists the idea, she is furious. She bursts out, “Countless Ramayanas have been composed before this. Do you know of one where Sita doesn’t go with Rama to the forest?” That clinches the argument, and she goes with him.”

What emerges from Ramanujan’s essay is not just that the Ramayana is a polymorphic tradition – it’s also a many-sided conversation, that spans cultures, languages, centuries and religions. There are Buddhist and Jain versions of the Ramayana. (The Patuas, an itinerant storytelling tribe, which my collaborator on Sita’s Ramayana, Moyna, belongs to, are a mixture of Muslims, Buddhists and Hindus who retell the Ramayana.)

There have been revolutions in the way the epic has been told. Retelling the Ramayana has sometimes been a subversive act, a political act – Molla, a Telegu poetess and a potter’s daughter, retold the Ramayana in simple language (in contrast to the ornate, inaccessible Sanskrit used by Brahmins) and thus made it accessible to everyone. The Kannada writer Kuvempu, who was also a Ram devotee, struggled with the treatment of Shambukha (the shudra who Ram beheads in the Uttara Kanda for performing tapasya, which causes the death of the Brahmin’s son) and wrote Shudra Tapasvi, which inverts the episode. Michael Madusudhan Dutt pioneered the use of blank verse in Bengali literature in the Meghnad Badh Kabya, a poem on Ravana’s son Meghnad (aka Indrajit).

I’ve been to shadow puppet performances and watched audiences laugh uproariously as retellers interpolated references to contemporary events (and even characters from the Arabian Nights) into their retellings. Scholars speculate that the story of Hanuman, traveling on the silk route centuries ago, inspired the tales of the Monkey God, Sun Wukong, the hero of the sixteenth century Chinese epic Journey to the West.

If we cease to acknowledge multiple retellings, we will forget the many reasons why the Ramayana is important, and forget how the story has travelled and the new forms it has taken. We will also discourage further retellings – and for the epic to remain alive and relevant to every generation – it must be retold in a way that reflects the anxieties and issues of that society.

A society that finds the idea of multiple retellings offensive and preserves only one version of the Ramayana silences inquiry into the epic, puts it on a pedestal. We cease to engage with the epic, its characters and their dilemmas.

It’s not in talk of a fabled golden era, an ideal state, or idealized, prescribed roles for men and women that I find a reflection of all my hopes for India. It’s in the polymorphous tradition that Ramanujan describes, in the many voices, retellings and languages of so many Ramayanas, that I find the best of what I love about India – a place of many voices, opinions, cultures, faiths and languages.

RECORDING WITHOUT END by Peter Pannke

Peter Pannke is a writer and also a musician and musicologist

for Alain Daniélou

Nada bheda aparampara para hu na payo guni

Gaye gaye thake sabe sura nara muni jana deva

Kete guni ghandarva kinnara thake thake brahmacari hare

Ina kina dou na payo tero sakala marama saba bheda

The knowledge of sound is without limit, even men of quality could not attain it.

They sang and sang, and in the end became tired, heroes, saints, and even gods.

So many experts, Gandharvas and Kinnaras became tired and failed in their discipline.

They, too, could not reach the eternal mystery, the completeness of knowledge.

In the medieval Dhrupad composition quoted above, we find expression of the idea, that the knowledge of sound is without any limit – even the gods could not reach the other shore of this vast “ocean of promise“ stretching beyond the horizon of audibility, much less so human beings.

What we are concerned with here is not the quest for inaudible sound, the ultimate aim of an Indian musician, but the transmission of audible sound from one culture to another. When we look back today on Alain Daniélou’s life and try to understand how he became a living link between two civilizations, there emerges the profile of a man who was a pioneer in many different fields, all of which seemed to be interrelated. As I want to deal here with the role recordings have played in his life and work, the ingenious way he has used them to promote an inter-cultural dialogue seems to be especially striking. He was in fact the first person to really understand the role the new medium of LP recordings would have to play, not only for the West but also for the East. He used recordings as catalyzers of cultural change at both ends. As the time was right for this, nobody was very surprised when he did it, but it was in fact something completely new. Up to the end of th 19th century, the medium of dialogue between cultures – other than trade and war, of course – had been the printed page. In the 20th century, cultural communication has been enhanced and put on a much broader basis through the development of the media, from wax cylinders to the phonograph, LPs, CDs, Video, DVD, TV, satellite communication systems and the Internet, which give us real time live contact with each other. As it is this development that provides us with the basic clues for the continuation of this encounter, I believe it is worth taking a look back at the situation Daniélou was confronted with when he began.

Alain Daniélou started his musical research by investigating the nature of sound, its organization and expression in intervals and musical scales. It was certainly no coincidence that his research finally led him to India – as it is probably India that has thought about this question most deeply and provided him with his most valuable clues. It was not his aim to describe an ethnic musical system. Right from the beginning he approached Indian music from a very different angle than all western ethnomusicologists before him.

The establishement of the academic discipline of comparative musicology was in fact triggered by Edison’s invention of the phonograph in 1877. Only seven years later, in 1885, Alexander J. Ellis published his treatise “On the Musical Scales of Various Nations“. Although he relied heavily on the evidence offered by non-European musicians and musicologists, he discarded their methods and findings as unscientific. Valuable musical abstractions should henceforth be based on “objective“ and “scientific“ research undertaken by Western scholars, as opposed to the “subjective“ perceptions and mythological conceptions of non-Western musicians and musicologists. The new science would primarily rely on Ellis’ invention of the cent system for measuring frequencies and the “objectivity“ it offered in analyzing phonograph recordings and musical instruments. Ellis concluded his paper with the comment that his research required “completion by the long and careful observation and study of many physicists who have some notion of music, rather than of musicians whose ears are trained to particular systems but with slight knowldge of physics”. It was clear from the beginning, that musicians and non-Western musicologists would be, for the greater part, excluded from this type of research. Nevertheless Ellis’ successors found his work so important and valuable that he was unanimously acclaimed as the founding father of comparative musicology.

It is interesting to see – just as Alexander J. Ellis had done before him – that Alain Daniélou started his investigation with a comparative study of musical scales. He explained the singularity of his approach very clearly: “The real problem is not to know how human beings may have acquired the knowledge of musical intervals, which always brings us back to a question of myth, ancient or modern, but to discover the real nature of the phenomenon by which some sounds combined to represent ideas, images or feelings. This we obviously cannot discover by experiments nor decide by vote. So we shall have to draw upon the data of traditional metaphysics which, under the divers forms which they may take, present always the same logical and coherent theory“. Before he wrote these lines in the opening chapter of his “Introduction to the Study of Musical Scales“, Alain Daniélou had settled in India, studied with traditional Indian musicologists, collected and translated musicological literature, learned to play the music himself and had virtually “gone native“ in order to, amongst other things, understand the way of thinking and living which underlies Indian music. Although this peripheral method was not the accepted approach in Western academic circles, it was not the only reason for the controversies he eventually stirred up in the field of musicology. His procedure, as we will see, questioned the very raison d’être of the whole discipline.

Comparative musicology, as pointed out by Warren Dwight Allan in his “Philosophy of Music History“ (1939), was built on modern myth: “By collecting, transcribing and analyzing recordings, comparative musicologists thought it would ultimately be possible to create an evolutionary classification system with “primitive“ music on the lowest branches of the tree, ancient and “oriental’ music somewhere in the middle and European art music at the top“. This was of course the Darwinistic doctrine of evolution, a product of the 19th century, and although Darwin himself believed that he “worked on true Baconian principles, and without any theory – collected facts on a wholesale scale“, the model underlying his thought was that of the tree of life, a mythic image familiar to us not only from Genesis, but also from Egyptian, Buddhist and Greek sources, among others. By the middle of the 20th century, the Baconian empiricism adopted by Charles Darwin – and after him the founders of comparative musicology – was no longer adequate to the idea of nature that science had developed. Einstein and Heisenberg made it clear that mind and nature – subject and object – are involved in each other and as a result of that cannot be seen as separate empires. An “objective“ world – or for that matter, music – that can be “observed“ and “understood“ if only imagination can be held in check is something that simply does not work.

Alain Daniélou had sensed these ideas long before they found their way into scientific theories and certainly long before they had respercussions in the field of musicology, Since the 1950s the term “comparative musicology“ was replaced by “ethnomusicology“ and the focus shifted from the laboratory to the field, from “primitive“ to urban and popular music and from the “quest for origins“ to the process of change and acculturation. But its basic premises have remained untouched. The reason for this is not lack of reflection, since ethnomusicology has tried to re-define and re-invent itself over and over again, but rather the structure of Western academic studies itself. When the founders of the discipline established themselves in the framework of European universities, they they were aware of their peripheral status and located their own discipline in an inferior position on the tree of knowledge, silently agreeing that Western musicology was superior.

This, of course, was beyond all question for Alain Daniélou. He gave a very vivid description of the spirit in which he conducted his inquiries: “We always appeared to be poking fun at everything“, he wrote, “not because we were frivolous, but in an attempt to discredit false thinking and get to the bottom of things“. This quality he so much admired in his companion Raymond Burnier. Having freed himself from the burden of Western academic concepts, he was able to approach the area of his interest from the most diverse angles. Actually he worked out a model of intercultural studies, which might have served as an example for a curriculum if hadn’t been such a challenge to the academic world. The real dilemma of comparative musicology lies in the fact that it simply could not deal with living music and living musicians, since it had never learned to speak their language and understand their beliefs.

Alain Daniélou went exactly in the opposite direction, not only by establishing himself in the field of his research and by sharing the life of the musicians, as no ethnomusicologist had ever done before him, but also by regarding the function of recordings. His first book on Indian music, published in 1943 by the Indian Society in London, remained virtually unnoticed by the public and was scarcely reviewed by the scientific community. It was only after World War II that it became possible to find sound reproduction systems that used other devices than the phonograph or cylinder engravings. Alain Daniélou immediately recognized the value that an actual recording of the music he had talked about would have: a value not only for researchers, but also for the public in general, and – last but not least – for the musicians themselves. It is quite charming to read in his autobiography how he acquired one of the first steel wire recorders and how he rushed from Benares to New York in order to buy the best available new magnetic tape recorder, the “Magnecorder“, a very bulky machine with two compartments that required a current adapter. As soon as he returned to Benares, he began to record some of the best classical musicians, Vedic chants and traditional popular songs of India. The immediate result was the publication of the first “Anthologie de la musique classique de l’India, by the French recording company Ducretet-Thompson. At the same time these recordings laid the foundation for the UNESCO collection, which became a monumental and pioneering work in the history of ethnomusicology. Alain Daniélou tells us in his autobiography that “for the first time since its creation, UNESCO, which until then had done little more than supported the Addis Abeba Philharmonic or the Teheran Opera, became involved in non-Western music.“ After the completion of this collection he learned to his great satisfaction “that the general director of this noble organization had declared the record anthologies one of its most important achievements“, even if UNESCO made no financial contribution to it at all.

“For Asian and African musicians, the UNESCO label carried a great deal of prestige and represented a kind of international consecration,“ wrote Alain Daniélou. Once they had been recorded, they became “international-class musicians“ and ceased to be neglected, scorned and ignored by their own governments. Radio stations began to play their music and their financial situation rapidly improved. In fact, these musicians became his allies when he established the International Institute for Comparative Music Studies and Documentation in Berlin in 1963: “I soon realized that my goals were so far removed from those of the university-trained folklorists and musicologists that no real cooperation was possible“, he wrote in his autobiography. “Our most valuable colleagues were the musicians and not the ethnologists and musicologists from the university. Musicians are instantly sensitive to the quality of music, its artistic worth, and the personality of the artist, even when the system is foreign to them“.

Even more significant than that – and this is the point I want to make here – is the fact that Alain Daniélou used a new medium, the LP, in order to bridge the division between the recording and the artist, whereas musicologists before him had separated music from the musicians in order to analyze it in their laboratories. Alain Daniélou gave music back to musicians, and in doing so, he initiated a cultural change we can still experience today.

Although he stated that he was “far less interested in attracting the attention of Westerners to Oriental music than in helping musicians maintain their traditions“, the effect that the publication of the UNESCO collection had on the Western public should not be underestimated. The records published by Alain Daniélou became a tool of cultural change that went far beyond the scope of music as such and participated in a process of social change characterized by the Vietnam war and the subsequent disenchantment of a whole generation of young Westerners with the accepted values and patterns of their own society. When they started to question the responsibilities of their governments, it was as if a spell had been taken away. Alain Daniélou had contributed to this process by managing to transport something of the essence of Oriental cultures to the West, not as much through his writings as through his endeavours to let the musicians talk, sing and play for themselves, and be listened to. By consciously stepping out of the role of a detached observer and accepting the responsibility of an agent of cultural change, he made an invaluable contribution and participated actively in the creation of a background for genuine cross-cultural dialogue.

Even if the prospects for this dialogue seem to be somewhat bleak at present, it has already shaped our lives to such a degree that we seem to take it for granted. Today, when CDs with recordings from almost every corner of the world fill the shelves of record shops and concerts of non-Western musicians have become part of our daily life, it is hard to remember that the publication of the UNESCO collection back in the 1960s was an epoch-making breakthrough into unknown musical territories. Before this publication, recordings of non-Western music were buried in ethnomusical archives. With the UNESCO collection – an enterprise only paralleled (to some degree) by the Folkways Collection build up in the United States by Moses Ash, though on very different lines – Alain Daniélou had, almost single-handedly, opened up a whole new dimension of musical experience for a much larger group of people than a circle of academicians.

In order to keep my observations short and yet establish a profile that in my opinion has scarcely been noticed, I have deliberately left out any discussion on Alain Daniélou’s achievements in other areas. We know, of course, that his book on “Ragas of Northern Indian Music“ proved to be a valuable and pioneering collection of materials from the Benares tradition, even more valuable today due to the fact that this tradition has virtually died out.

When we look back today on Alain Daniélou’s life, I think we should not only ask what he did, but also what he left for us to do. The imminent closing down of the institute he established in Berlin more than 30 years ago – recently announced by the Berlin Senate – only underlines the fact that a redefinition of the role that music can and must play in our present situation is long overdue. It is quite ironic that the arguments Alain Daniélou developed as UNESCO adviser in his passionate pamphlet on the situation of music and musicians in countries of the Orient are being carried out by ethnomusicologists today only as an empty rhetorical exercise devoid of any practical consequences. In fact, ethnomusicologists seem to be more endangered than musicians themselves. In radio departments or print media there are hardly any ethnomusicologists to be found, and for the TV industry traditional music does not even seem to exist. Record publications and the organization of concerts have been taken over by a new brand of young world music enthusiasts, but the cross-cultural dialogue initiated in the 60‘s with the explicit aim of putting the traditional artists of the Orient on an equal standing with the classical musicians of the Western world seems to have declined and shifted to the mingling of cultures on the level of contemporary urban pop music. Traditional musicians are in need of a spokesman on this global scene of cultural change more than ever. What is lacking today is a coherent line of argument in order to convince politicians and the powers behind the media of the value of and the need for these musicians in the context of the present social and political upheaval surrounding us.

The answer to this can be probably found on a horizontal level rather than on a vertical one. Rather than new institutions, what we need is a global network connecting individuals – musicians, scientists, media people, social workers as well as institutions from the most diverse fields. The investigation into the nature of sound, to which I alluded at the beginning of this text, could and is about to reveal very astonishing results in the field of applied physics. We can definitely learn a lot from the structure of traditional performance and living spaces for the planning and construction of concert halls, museums and cities. And certainly the contact between composers and musicians has to be continued. More than anything else, it is the media which has to come into the picture and vice versa, as it is the media which has shaped and changed our lives in the last 50 years to a degree we hardly realize.

It is quite amazing for me to see that we have not even begun to understand the real nature of an acoustic document. In the 19th century it took people quite some time to learn how to differentiate between a photograph and the object or person depicted. And when the first films were shown, exactly 100 years ago, the audience left in panic when they saw a train engine apparently entering the hall from the screen. By now the differentiation between an object and its image has become a part of our cultural perception. But recordings of music seem still to be taken for the real thing instead of being recognized as a magnetic shadow on a tape or a digital code on a CD. As long as it is convenient for people to replay these acoustic shadows or digital codes (devoid of any spatial information) for entertainment, it is fine. The fact that there are still people who believe that it is possible to arrive at any valid conclusion about the nature of a music by analyzing a mere recording of it, is on the other hand quite amazing.

In order to provide a memento of this talk, I have produced a little objet d’art which is intended to contain the essential spiritual and material elements that brought us here today. It is a CD with a recording of the elder Dagar Brothers, N. Moinuddin and N. Aminuddin Dagar, the first Indian musicians Alain Daniélou invited to Europe when he had established the International Institute for Comparative Music Studies and Documentation and the first to be published in the UNESCO collection. This is also a tribute to the fact that, without Alain Daniélou, the Dhrupad would not have survived and experienced the modest revival it has gone through since this first LP appeared. It is also a very personal “thank you”, since it was this very recording that persuaded me to follow Alain Daniélou’s footsteps to India and trace these musicians myself.

However, when he played these recordings in October 1964 in Berlin, all of a sudden the tape ran out before the singers had finished their last and most beautiful rendering of a Dhamar composition in Rag Jayajayavanti. Shortly afterwards N. Moinuddin, the eldest of the Dagar Brothers, died. As a result of that, the last recording of the elder Dagar Brothers was never published, but Alain Daniélou preserved it in his private archives and I present it to you today as a beautiful poetic symbol of our never-ending efforts to capture sounds and of the dis-synchronicity of technological and musical time. It is encased in a marble plaque carved in India in the area of Braj, the sacred “forest of love“ mentioned in the composition. The plate bears the Hindu name of Alain Daniélou and the number of the copy, as this object has been published only in a limited edition of 27 copies. 27 of course, represents 108, the number of completeness in the Hindu tradition and, amongst many other things, the number of prayer beads in an Indian mala. It is covered by a plexiglass plate manufactured in Berlin, the other geographical end of Alain Daniélou’s way through the labyrinth of sounds. The golden screw, connecting these two material elements of east and west, which you loosen to take out the recording and listen to it, symbolizes the golden alchemical thread Alain Daniélou has woven between east and west.

“Registrazione senza Fine“ is written on it, in an attempt to remind you that Alain Daniélou’s work is not completed yet and has to be continued by us. Let me close with the text of the Dhamar composition which is sung on it by N. Moinuddin and N. Aminuddin Dagar:

Raga Jayajayavanti – Dhamar

Hom cita cahata piya ke milanako

Hom to nírasa bhai Brindavana basake

Kara curi phora darun moti mala tora darun

Kajara main dhoye darun Jamana me dhasake

(Author: Baiju Bhavra, 16th century)

My heart is waiting for the return of my beloved,

Since I live without hope in the garden of love.

I will break my bracelets and tear off my necklace

And wash away my mascara by throwing myself into the river Jamuna

WAYS OF ENGAGING – COMPELLING IMAGES BY DANIÉLOU & BURNIER

by Malavika Karlekar

Malavika Karlekar is the editor of the Indian Journal of Gender Studies

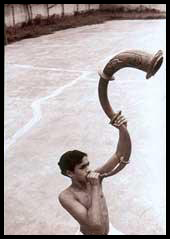

Ravi Shankar blowing on the ransin

As the camera moved in to share visual space with the sketch book, crayons and water colours, professional photographers as well as eager amateurs became accomplished recorders of a changing India. Among the foreign photographers whose images are perhaps best remembered are Margaret Bourke-White and Henri Cartier-Bresson. Apart from the sheer brilliance of many of their visuals, they were recording the cataclysmic India of the mid-1940s, and therefore they find a place in public memory. Some of these images have an immediate mnemonic resonance for many Indians, like Bourke-White’s iconic image of Gandhiji spinning in half-light and, as she wrote, that of the “dramatically handsome” Jinnah, the many horrific and at times poignant photographs of 1947, and Cartier-Bresson’s testimony of the easy camaraderie between Edwina Mountbatten and Jawaharlal Nehru.

Some photographers had official approbation, others worked away quietly – their work barely known at the time. And then there were those whose images were displayed in the early years of Independence, succeeded by a period of hibernation and afterwards a re-emergence in the 1990s, as the world became increasingly aware of the value of the archival photograph. In 1948, at the first photographic exhibition held at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, the first images of Khajuraho were on display. These photographs had been taken by the young Swiss photographer Raymond Burnier and the Frenchman Alain Daniélou, a musicologist, artist, writer and, of course, also a traveller and photographer.

In 1932, the two men came to Shantiniketan, where they spent four years at the invitation of Rabindranath Tagore. They soon became an integral part of the syncretistic vision of the institution; Burnier’s Leica framed the poet, the unique buildings of the educational complex, its students and the general ambience, which subtly merged the lushness of rural Bengal with understated structures Daniélou on his part actively collaborated in a musical enterprise. In his autobiography The Way to the Labyrinth: Memories of East and West, he wrote that as “the poet was a great universalist and wanted his musical works to be known outside India”, he asked the Frenchman to undertake the job of transcription and arrangement of some of his songs “so that they could be performed by Westerners”. Spending many days “lying on the grass… hummering [sic] the melodies and attempting to find French or English words that could be inserted into the melodic form”, Daniélou pursued a task that required “endless rephrasing and readjustments”. After the death of “Gurudev, the Divine Master, with whom I had spent my first years discovering India”, he was asked by the poet’s son, Rathindranath, to provide an orchestral version for Jana Gana Mana. Aware of the sensitive nature of the task, Daniélou adds that he “made a quick trip to Paris to ask my old friend and master, Max d’Ollone, to check over my work. We rapidly composed arrangements for orchestra and brass band”.

By the end of the 1930s, when Daniélou and Burnier moved to Varanasi, they began a fascinating process of visually documenting Indian society. There was e very good exhibition of their oeuvre — India through the lenses of Alain Daniélou and Raymond Burnier —, recently held at the India International Centre in New Delhi. Organized primarily by the Alain Daniélou India committee, this selection of 42 black-and-white photographs from the many thousands in the Alain Daniélou/Raymond Burnier photo collection represent the various phases in the life of the two artists. While the curatorial team points out that “authorship” of individual photographs is not always clear, Daniélou’s images with his Rolleiflex concentrated more on social aspects whereas Burnier focused on sculpture and temple architecture.

Their usual mode of conveyance for over hundreds of miles was a car with a trailer imported from the United States hitched to it. Rewa Kothi, a palace rented from the Maharaja of Rewoverlooking Varanasi’s Assi Ghat, became Daniélou and Burnier’s home, “a palace hospitable to musicians, prestigious personalities, wandering monks as well as migratory birds and monkeys”. While these figures are not represented in the present exhibition, the intricate tapestry of life in the Kothi is brought alive by many photographs that invite the viewer to participate. A long top shot by Burnier captures Alain studying in what appears to be the baithak khana, aglow with sunlight pouring in from the French windows. Daniélou sits comfortably on a takht with bolsters all around, and the camera doesn’t miss a corner of the horizontal cloth pankha as well as the gallery above — perhaps used by ladies of the zenana in an earlier life of the Kothi.

Conventional shots of Varanasi, its ghats, and the wildly billowing sails of boats during the monsoons are offset by powerful images of the male body. In the entire exhibition there is not a single image featuring a woman or a girl. There is Ramprasad, the boatman, cheerfully oblivious of the fact that the world will see him clad in only a langot, and the sculpted Kelo Nayar, a Kathak dancer, as he poses on what appears to be a precarious parapet. His well-oiled muscles that ripple with an unmistakable sensuality mesmerize the viewer, as does his direct and almost arrogant gaze. Photographer and subject had clearly spent considerable time in composing the image where the dancer puts his weight on his right hand and his left leg and arm are stretched taut, glistening in what was possibly a hot north Indian day. He too is is also wearing a langot’.

Daniélou’s musical background attracted a number of young performers to Rewa Kothi and the camera is used to reach out to the intense concentration in a group of kirtan singers and the furrowed brow of a young flautist, a sadhu with ringlets and wisps of hair flowing through his long fingers that wind delicately around his instrument. Qawals, veena and shehnai players are represented, usually in semi-profile, in compositions using background, light and shade imaginatively. Hira Lal and Shyam Lal lean against each other as they play their flutes, a synergy flowing through their lithe bodies. Rewa Kothi was now a salon de musique, hosting the youthful Ravi Shankar, Alla Rakha and the Dagar brothers. Daniélou did the first recording of Ravi Shankar, and there is a somewhat formulaic composition of him playing the esraj whilst he leans against a pillar, a half smile on his lips. On the other hand, in this far more dramatic image of Ravi Shankar blowing on the ransin (picture), the photographer has taken the shot from a slight elevation, absorbing into the frame the entire sweep of the large Himalayan trumpet as also the paved area — maybe a courtyard — sloping away into the distance. Ravi Shankar occupies only about a third of the photograph, and though the huge trumpet dominates somewhat, the curve of the ground cover at the edge of the image – which was not cropped –, gives a sense of infinity.

The Rewa Kothi photo studio continued till 1954, and during these years Daniélou and Burnier travelled widely, consolidating their growing portfolios with detailed photographs of temple architecture and sculpture. In many of them, the focus was on musical instruments, in others it was eroticism that absorbed them. Neither Burnier’s camera nor Daniélou’s paints and pencil were ever far away. A viewing of even a fraction of their work enables us to enter the world view of two men who were born Europeans but adopted India as their home for a good part of their creative lives. Though by the mid-1950s the two men were back in Europe and lived separately, their earlier joint photographic work is a significant contribution to portraiture: in many images, it is as though the subjects imaginatively composed and placed within frames were seeking to engage — if not converse — with the viewer. The era of the “mould of the mugshot”, if one can put it that way, was clearly over.

PARALLEL CINEMA IN INDIA by Himadri Ketu

Himadri Ketu is Hindi Teacher and researcher at the University of Munich, Germany

A still from the film Pather Panchali (1955), considered the first Parallel Film of India.

Indian cinema completed its centenary last year since the release of its first feature film Raja Harishchandra by D.G. Phalke in 1913, but in fact the history of Indian cinema goes back to 1897, when short films were already being made on India’s freedom movement. Since then the Indian film industry has grown enormously and has become the third largest in the world: it releases over 1000 films every year in several languages (Gopalan 2009: 1). Bollywood is the popular name of the commercial Indian film industry and is mainly focused upon Hindi cinema. India has several hundred languages, out of which only 22 are recognized in the constitution, but since Hindi is the lingua franca, it is widely understood in all states across India. For this reason Hindi cinema enjoys its status of being Indian cinema, whereas films in regional languages (like Bengali, Bhojpuri, Guajarati, Kannada, Malayalam, Marathi, Oriya, Tamil, Telugu, etc) are in general low-budget movies with limited viewing due to the language barrier.

This article intends to give an introduction to Parallel Cinema in India, a phenomenon emerging first in regional cinema and then in Hindi cinema during the 1960s as a protest against commercial Indian cinema, i.e. popular Bollywood, which has been identified as “escapist entertainment and street busters” (cf. in Saari 2009: vii). Despite its popularity among the masses the film critic Chidananda Dasgupta refers to Indian cinema as being neither Indian nor cinema (Dasgupta 1969: 28). The trouble he sees with Hindi cinema is not that it is commercial; something that can be applied to all film industries in the world, but that Hindi cinema does not equate commercial films with artistic productions, something which other film industries do. The success of an Indian film depends first of all on the stars playing in it, the music director, to some extent the script writer and finally the director. The impersonality of the film, which implies the minimal role played by the director, makes films too bland and formulaic (Dasgupta 1980: 36).

On the other hand regional films show a greater sense of reality and deal with contemporary social problems that Dasgupta regards as pretty much Indian – though not quite cinematic. In general Indian cinema replaces regional characteristics with subjects of wider acceptability, although till 1960 Hindi cinema was equally sensitive to social issues and portrayed the evils of the caste system and exploitation of poor peasants in films like Achhut Kanya (Untouchable Girl, 1936) and Neecha Nagar (Lowly City, 1946). These films were deeply influenced by social realism and depicted the problems of rural India. The 1950’s are considered the ‘Golden Age’ of Indian cinema due to the films of Guru Dutt, Bimal Roy and Raj Kapoor who addressed the problems of ordinary people in modern Indian cities. In contrast to this, the 1960s represent deterioration in the aesthetics of Indian cinema, because films started to function only as dream factories and provided an escape from poverty and daily problems. This change was due to a striking increase of freelance film producers who turned socially conscious movies into mass consumer goods.

It is as a reaction against this tendency in Indian cinema that the ‘Parallel Cinema’, also called ‘New Wave Cinema’ or ‘Art Cinema’, was launched in the 1960s by a few young film makers from the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), an autonomous body set up by the government. The leading filmmakers of this new cinema were Mrinal Sen, Mani Kaul, Shyam Benegal and Govind Nihalani, although Satyajit Ray remains the father figure of Parallel Cinema with his Bengali film Pather Panchali (Song of the Little Road, 1955) which showed the personal touch of Ray in every aspect, devoid of any songs or stars. In the 1950s and 1960s the directors Satyajit Ray, Ritwik Ghatak, Tapan Sinha and Tarun Majumdar transformed Bengali cinema and became the pioneers of the so-called ‘Parallel Cinema in India’. Thus the Parallel Cinema movement started in the regional cinema first and then extended afterwards to Hindi cinema.