“Without contraries there is no Progression”

William Blake

Index:

- » NOTE ON THE DEPARTURE OF DIRECTOR ION DE LA RIVA

- » AMBASSADOR ION DE LA RIVA, RECOMMENDS…

- » MANIMEKHALAI, THE DANCER WITH THE MAGIC BOWL a glance at the Italian edition by Petra Lanza

- » THE BODY IN INDIAN ART: Erotic art: propitious, apotropaic, sensual or transformative? by Heather Elgood

- » SHARPENER OF SOULS by Aveek Sen

- » THE TEMPLE AND THE BODY: DANIÉLOU ON THE VERTICAL AXIS OF EXISTENCE by Adrián Navigante

- » THE KATHPUTLI COLONY DIARIES by Sunayana Wadhawan, on behalf of the Kathputli Colony residents

- » RABINDRANATH TAGORE: CENTENARY OF A NOBEL PRIZE (1913-2013) by Prithwin Mukherjee

- » THE BODY CONFERENCE Alain Daniélou Foundation’s – Talks at the Labyrinth 2013

- » 50th ANNIVERSARY OF THE FOUNDATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE

- » A LETTER FROM… LA HAYA by Ashok Patak

- » A LETTER FROM… INDIA by Manu Chao

- » Alain Daniélou Foundation’s 2014 RESIDENCY PROGRAMME

- » Alain Daniélou Foundation’s UPCOMING EVENTS 2014

- » Alain Daniélou Foundation’s PROPOSALS 2014

NOTE ON THE DEPARTURE OF DIRECTOR ION DE LA RIVA

An announcement by Thierry de Boccard, Alain Daniélou Foundation’s President, and Ion de la Riva, Alain Daniélou Foundation’s former Director, was sent last January 30th to the members of our Honorary Board and Advisory Committee, as well as to our close collaborators and partners.

The letter noted Ion de la Riva’s admirable work in launching a new phase of the Foundation last year. In addition to this, the Board of Directors thanked Ambassador de la Riva for his decisive actions in giving the Foundation visibility at international level and starting this new phase of its activity.

Jacques Cloarec, the legal representative of the Alain Daniélou Foundation in Italy, has taken on the management of the Foundation, which will continue this year with the same staff. In keeping with its mission and objectives, Alain Daniélou Foundation will continue to promote and foster artistic and cultural activities between India and Europe.

For information regarding events, projects and residency programmes scheduled for this year, please consult our website: www.fondationalaindanielou.org or contact us at the following email address: info@fondationalaindanielou.org.

AMBASSADOR ION DE LA RIVA, RECOMMENDS…

I hope you have had a great start to the Springtime!

For this inspiring season, I strongly recommend reading Revolution from Above, by Dipankar Gupta. It’s a short essay which appropriately coins the term “citizen elite” to describe reforms by the bourgeoisie which help bring about social change and progress. Gupta first illustrates the case of such reforms in Victorian England and Prussia – two countries that were neither socialist nor revolutionary. He argues that it is not only in prosperous economic cycles that the elite classes feel more generous towards the disfavoured, and that it is not only as a reaction to pressure from the underclasses that the elite classes act to create a fairer society of true citizens. He argues these two points brilliantly and provides a lot of documentary evidence.

He then turns to the case of India, with regard to which he explains why essential welfare reforms are feasible and could work to achieve the general progress of the country. I should like Dipankar Gupta to analyse why nowadays some European countries are dismantling their welfare states, not just because of the global crisis, but because they are deemed to have given rise to abuses and dysfunctions. Some people, such as the Dutch socialists, advocate a new kind of social deal, no longer based on the traditional welfare state but on another formula. Dipankar Gupta takes the example of the Basque Country, straddling along the western Pyrenees between France and Spain, to showcase some of his hypotheses on the citizen elite. As a Basque, I feel his insight into my country’s efforts to make life more prosperous and fairer for all since Franco’s death is very accurate and well-explained. Thanks, Dipankar.

Gupta recently presented his book in Bilbao as well as in Delhi and Kolkata. We Basques love this book, which has put us on the map of India in a good light. The book can be strongly recommended to anyone interested in India and the dilemmas it faces with growth and progress. This is particularly pertinent as we approach election time in India and see the BJP and Congress parties’ with their different proposals to overcome poverty and injustice. In my opinion, Modi and Rahul would both benefit from reading this excellent book!

I also recommend the new edition of Saleem Kidway’s book on same-sex relationships in India. These are sad and shocking times for the GLTB community with regard to Supreme Court decisions on homosexual relations. The country that gave the world the Kama Sutra should not take a bigoted and puritanical stance on relations that have existed and will exist as long as men and women relate erotically and sexually to their own sex.

Concerning music, those of you who are not able to see Phillip Glass’ opera Satyagraha, should try and get a copy on DVD. And for our Indian friends, here are some books from the West that I recommend: Love and Intimacy, by John Armstrong, in order to understand our Western dilemmas of love and marriage; Edward St. Aubyn novels (an insight into sexual abuse and black humour from one of the finest living European writers), and Going Sane by John Phillips, to understand to what extent we are all misfits in one way or another. Other good reads are Javier Marias’ last novel Los Enamoramientos (now available in English) and Indignez-vous by Stéphane Hessel.

Finally, if you happen to be in Europe, please go and see Dayanita Singh’s show at the Hayward Gallery in London. And if you are in India, watch out for exhibitions at the wonderful Kriti Gallery in Varanasi and for performances organized the Neemrana Group, founded by recently deceased Francis Wacziarg. Francis did a wonderful job in rendering Western music more accessible in India, and we count on Jordi Savall to do the same for Indian music in the West.

Have a wonderful time with these musical and literary suggestions!

Ion de la Riva

Ambassador Ion de la Riva, former Director of the Alain Daniélou Foundation, is now in the Basque country as an advisor to the Global Board of the President, where he intends to develop academic and corporate links to India. He is also,c ourtesy of Agustín Pániker and Javier García de Andoin, at the Honourary Board of the Bilbao-India 2015 Programme of events and preparing a new book.

MANIMEKHALAI, THE DANCER WITH THE MAGIC BOWL a glance at the Italian edition by Petra Lanza

Casadeilibri Editore, an Italian publishing that has mainly focused on Eastern traditions ever since its birth in 2004 (this year is its tenth anniversary) has always stood out for its Italian translations of Alain Daniélou’s books; indeed, its first publication was La Via del Labirinto in 2004 (Eng. The Way to the Labyrinth). The latest of Daniélou’s works Manimekhalai, la Ragazza con la Ciotola Magica, was printed in late November 2013 in collaboration with the Alain Daniélou Foundation and was officially released at the beginning of 2014, along with La Fantasia degli Dèi (Eng. While the Gods Play). But let’s take a step back before introducing the Italian edition.

Fig 1: Cover of Manimekalai’s Italian edition by Casa dei Libri

Fig 1: Cover of Manimekalai’s Italian edition by Casa dei LibriAlain Daniélou first translated Manimekhalai in 1985 from Tamil into French, his mother tongue. No European language translations existed until then and even nowadays the book and the story it tells are little known even in India, unlike the Shilappadikaram, which is quite popular and which now boasts a museum dedicated to the Epic; the Silappathikara Art Gallery in Puhar, houses a series of sculptures and pictorial scenes from the saga. Both these epics were translated by Daniélou from Tamil into French; the French translation of Shilappadikaram was commissioned by UNESCO and paved the way for other foreign language translations of the book (there is even a Japanese translation, published in 1991.

The English preface of the Manimekhalai by Alain Daniélou (Eng. translation 1989), which represents the sequel of the Shilappadikaram, begins thus:

“Almost nothing is known of India, its daily life and institutions, in the troubled years of the first centuries of Christian era. The Manimekhalai, one of the masterpieces of Tamil literature, gives us, in the form of a didactic novel full of freshness and poetry, a delightful insight into the ways of life, the pleasures, beliefs, and philosophical concepts of a refined civilization. The story relates the adventures of a dancing girl who becomes a convert to Buddhism, a rather new creed at the time in South India. Tamil is the main pre-Aryan language still surviving today. The Manimekhalai calls into question many of our received ideas concerning ancient India as well as our interpretation of the sources of its present-day religion and philosophy. In its clear accounts of the philosophical concepts of the time, the Manimekhalai presents the various currents of pre-Aryan thought (mainly preserved by the Ajivika ascetics and Jain monks) which gradually influenced the Vedic Aryan world and became an essential part of it and, through Buddhism, spread over the whole of the Far East and Central Asia.”

More than one book was referred to when preparing the Italian edition of the text. This same technique—known as collation—was also used for the Italian translation of Manimekhalai. The Italian translator Pietro Faiella stated that French edition accompanied him throughout the main part of his adventure as a translator, nonetheless he relied on the English edition for some passages pertaining to Indian philosophy.

The Italian publisher’s note in the new edition by Lorenzo Casadei begins as follows:

Manimekhalai follows the epic novel of Shilappadikaram, published in 2011. Manimekhalai constitutes one of the most relevant compositions of ancient Tamil literature that has endured throughout the centuries, besides being one of the two most ancient examples of novel of universal literature. Manimekhalai, signed by the Merchant-Prince Shattan (or Sithalai Sattanar), was brought back to life in 1898 by U. V. Swaminatha Iyer (1855-1942). Being the only Tamil written Buddhist epic surviving from ancient times—perhaps thanks to its natural relationship with Shilappadikaram—, Manimekhalai represents a one-of-a-kind composition.

Both works were translated into French for the first time by Alain Daniélou with the assistance of two Indian pandits. R.S. Desikan contributed to the translation of Shilappadikaram, while for the translation of Manimekhalai, Daniélou was assisted by T.V. Gopala Iyer, widely considered as a first-rate Indologist and who passed away in 2007. Their edition of Manimekhalai is the most recent Western language version of the book. The publication of these two classical Tamil literary works occurred within a surprisingly short lapse of time (Éditions du Rocher 1985, Flammarion 1987), yet Alain Daniélou’s two introductions differ in dating the original works. As Jacques Cloarec explained, Daniélou cared more about the beauty of these works rather than in providing a precise dating of them.

Daniélou had already come across various passages of Manimekhalai while translating La Fantasia degli Dèi (Eng. While the Gods Play), recently published as part of the same collection, and in so doing he relied on the partial English translation by S. Krishnaswami Aiyangar. An attentive reader will certainly notice that the two versions differ significantly from each other. In the French editions of the text, The Teaching of Aravana Adigal from verse 38 to verse 472 of canto XXIX and from verse 20 to 255 of canto XXX are included in the Appendix so as to lighten the book somewhat. On the other hand, we chose to include these verses according to the original text, so that thyou will find them contextually within the chapters, alongside the lines of the English edition (New Directions).

For the French edition, Daniélou eventually decided to add the following subtitle: Le Scandale de la Vertu, presumably rewording the Marquise De Sade’s famous work Justine, ou les Infortunes de la Vertu. Indeed, Manimekhalai represents an apology for righteousness from a Buddhist perspective and righteousness itself becomes embodied in the graceful shape of the virtuous female main character.

This book seems to be at the basis for a deeper comprehension of the ancient Indian Buddhism of the Great Vehicle, as well as the spectrum of different traditions with which Buddhism would come in contact with in its journey through the Asian continent, while fading away in its homeland. The tiny island of Manipallavam (better known as Nainathivu or Nainatheevu, named after the famous Naga people, who according to Dravidic traditions were snake-worshippers) is where Manimekhalai manages to dispel the gloom of ignorance at the sight of Buddha’s footprints. Located further north than Sri Lanka, it is a sacred location of Shakti worship or, more precisely, one of the 64 shati pithas revered by Shaivas. Hence, traces can be conjetured of the intimate relationship between Tantric Shivaism and Mahayana tradition, to which the Nagarjuna legends seem to refer.

Finally, it seems worth noticing that the recurrent subject of the transmigration of souls, which forms the background to this tale, is presented through a fictional lens in the Manimekhalai and cannot be confused with the phenomenon of reincarnation as it has subsequently been perceived in Western countries and cultures. In Mahayana Buddhism, the concept of a permanent self does not exist, nor that any individual soul can be reincarnated in a another body. It is the continuum of consciousness (Chit) which is passed down from one life to another, just like the reader’s mind in a novel.

It took the Italian edition of Manimekhalai — based on Daniélou’s first translation — nearly 30 years to come to light. We hope that many other translations will follow ours, as this timeless book can tell us much about the millennial Indian culture, by often questioning our Western clichés and dispelling as did Manimekhalai the gloom of ignorance and prejudice.

Fig 2: Tamil palm leaf

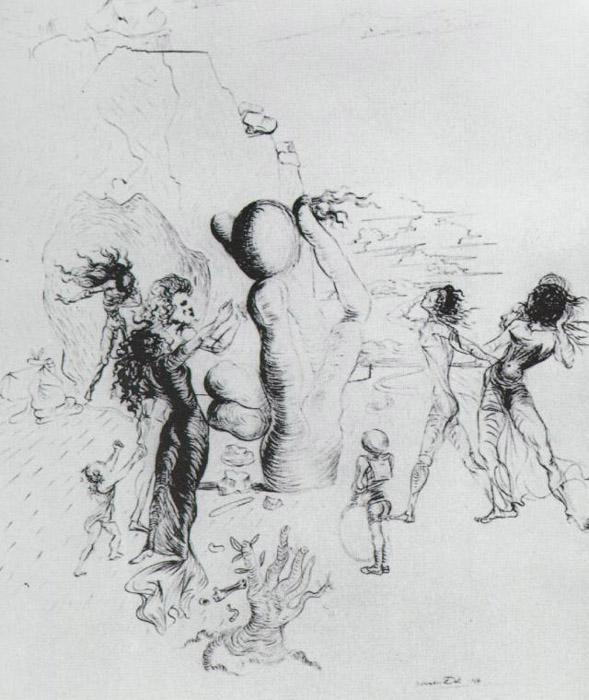

THE BODY IN INDIAN ART: Erotic art: propitious, apotropaic, sensual or transformative? by Heather Elgood

This paper will explore some attitudes to the human body in the Indian subcontinent through the development of erotic imagery from the second century BC to the twelfth century AD.

» Click here to see all the illustrations

The human body can be defined not only by its visible anatomy but also by the existence of a hidden body or self that is referred to by the Svetasvatara Upanishad (3.11-20) – “subtler than the subtlest, greater than the greatest is the Self (Atman) that is established here in the heart of a living being” (1). From the fifth century AD the inspiration of the Agamas, Samhitas (ritual texts) and Tantras led to a perception of the inner body as a network of fine psycho/sexual energies or substances which were channelled between the sexual region and the cranium through the spinal column. The basic yogic posture and techniques of breath control were mentioned in the Svetasvatara Upanisad (2.8-13) and the Chandogya Upanisad (8 6 .6) referred to nadis (veins or nerves) alongside the spinal column. Tantrics believe that the pathway to enlightenment is through the transformation of man’s subtle body and psychic energies. There are a number of different practices and rituals, some distinctively sexual, which are referred to collectively as “Tantra”. This is not to be confused with texts that call themselves Tantras which are a collection of animal stories and fables, not in themselves prescriptive, known as the Pancatantra (literally the five treatises). Much controversy surrounds the definition of Tantrism. David White defined Tantra as “a body of beliefs and practices which, working from the principle that the universe we experience is nothing other than the concrete manifestation of the divine energy of the Godhead that creates and maintains that universe, seeks to ritually appropriate and channel that energy, within the human microcosm, in creative and emancipatory ways” (2). While Gavin Flood strongly argues for the significance of power or siddhas as an objective of Tantric practice and a link between this and the divinisation of the body (3). Archaeological evidence from the second millennium BC and some textual references suggest an ancient substratum of beliefs from Harappan, Vedic, Iranian and indigenous traditions. For example, Figure 1 shows the cross-legged image from a Harappan seal which by virtue of its posture suggests yogic practices, and by extension breath control (4). Evidence of states of ecstasy can be inferred in references to “wild men” in the Rg Veda (10.1 36). These men known as munis or seers were believed to experience altered states of consciousness and to have magical powers including the ability to fly.

Fig 1

Fig 1

The origins of Tantra are difficult to discern, but it has been suggested that it emerged from the North Indian elite some time in the middle of the first millennium BC. White suggests a strong link between Tantrism and the Hindu alchemical tradition, arguing that Tantrism may, like alchemy, may have arisen in the Himalayas and Vindhyas, the mountains extending from Afghanistan and Baluchistan in the West to Assam in the East (5). The form of Tantra which was developed in northern India between the sixth and seventh century AD is the final phase of an earlier canon which referred to itself as “Kula-Dharma or Clan Practice”. This initially involved adherents such as the Kapalikas, whose rituals centred on the worship of Siva-Bhairava and his consort (6) on the cremation ground. The Kula sect was first mentioned in seventh century Hindu and Buddhist sources. This cult was reformed in the ninth century by Macchanda-Matsyendra who became the founding guru of the Kaula sect and author of the ninth tenth century Kaulanananirnaya (7).

Kaula rituals favoured the erotic elements of the yogini cults over the mortuary aspects of Kula rituals. Sexual intercourse became the means for generating the sexual fluids that were offered to the tantric deities. Prescriptive texts referred not only to sound (mantras) and visual diagrams (yantras) but also to the literal or metaphorical transmission and transformation of bodily fluids or substances. Kaula rituals sought power and immortality through the exchange and transmutation of bodily substances by means of sexual union, while the mobilisation of sexual fluids was dependent on yogic breathing, mantras and the visualisation of yantras and deities. Menstrual or female sexual fluids were believed to be initially absorbed through the phallus after which they united with semen within the male body. This mixture then rose like sap from the abdomen, passing through the channels along the spine and being purified in its passage through the cakras. Its ultimate destination was the ajna cakra, the sixth of the yogic centres, located in the cranial region behind the eyebrows, the seat of the nectar of immortality (8).

In the eleventh century AD, Abhinavagupta and his disciple Ksemaraja established a right-handed tantrism called Srividya Kaula, which reduced the physical aspects of left-handed Tantra to the status of a symbolic metaphor. In right-handed Tantrism the sexual emphasis and the literal transformation of fluids or substances, which was such a feature of left-handed Tantric tradition, became transformed into a more cerebral search for an expanded consciousness with an emphasis on sound vibration and transcendental awareness. During this period, left-handed Kaula adherents continued to engage in sexual ritual, made blood offerings and strove for worldly powers and immortality. The right-handed practitioners aimed at a theoretical interiorisation of the male/female union in their own physical bodies. They emphasised the refinement of energies or prana in the body, through the control of breath, the use of mantras, the vibration of sound, body heat, control of the mind and visualisation (9). Left-handed Tantrikas sought to obtain magical powers or siddhas including bodily invulnerability (kaya-siddhi) or immortality (deva-deha) and a range of sexual powers. Contrary to this, the aim of the right-handed Tantrika was moksa, that is release from reincarnation and the realisation of God (10). This shift in emphasis to the less literal made Tantric practice more widely acceptable, while the initiated adherents still observed many of the original early practices in secret (11).

This paper explores firstly the development of sexual imagery in ancient India from the second millennium BC to the first century AD, interpreted as apotropaic (magico-protective), propitious or generative. Secondly, it considers the significance of terracotta plaques from the second century BC which depict mithuna (loving couples) and maithuna (explicit coupling) (12), an art form popular among town dwellers in the burgeoning urban mercantile communities. Thirdly, it examines the architectural and textual evidence from the first century AD, which reveal dionysiac-inspired cults, a practice originating from the third century BC Greco-Bactrian community of the North West Indian region of Gandhara. It argues that these cults suggest a growing interest in sensuality and pleasure or bhoga. Fourthly, it considers the impact of Tantrism on tenth to twelfth century temple architecture, temple ritual and figural sculpture from Orissa and Central Indian temples. It shows that Tantric ideas inspired drama and secular literature such as the Kama Sutra and it focus specifically on the erotic sculpture found on the juncture walls of the shrines and halls of certain temples, for example in Orissa, as well as on the Lakshmana (tenth century) and Kandariya Mahadeo (eleventh century) temples at Khajuraho. Finally, it considers these images in the light of left- or right-handed Tantric practice and, at the same time, it bears in mind the extent to which these phenomena paralleled the science of alchemy.

According to the scholar Partha Mitter “in Great Britain there was no history of the appreciation of the visual arts of India…. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, multi-armed and multi-headed gods of Hinduism were perceived as unnatural, and likened to the serpent or Pan-like images of the Devil” (13). Mitter suggests, however, that a rise in the scientific interest in paganism during the eighteenth century led to a more serious study of Hindu mythology, which drew on Indian literary sources and popular paintings (14). Despite a strong puritanical backlash from 1837-1901, the discovery of Sanskrit marked a more systematic approach to the study of Indian art and architecture. Ram Raz, for example, was encouraged by an English resident Richard Clarke to translate some prescriptive texts known as the Silpa Sastras (15).

”I found… seven Hindoo temples, most beautifully and exquisitely carved as to workmanship……… indeed some of the sculptures here were extremely indecent and offensive, which I was at first much surprised to find in temples that are professed to be erected for good purposes, and on account of religion. But the religion of the ancient Hindoos cannot have been very chaste if it induced people under the cloak of religion to design the most disgraceful representations to desecrate their ecclesiastial erections. The palanquin bearers, however, appeared to take great delight at those, to them very agreeable novelties which they took great care to point out to all present” (16).

In the early twentieth century, Havell stated with rare insight that “Indian artistic expression begins from a starting point far removed from that of the European. Only an infinitesimal number of Europeans – even of those who pass the best part of their lives in India make any attempt to understand the philosophical, religious, mythological and historical ideas of which Indian art is the embodiment (17).

A common theme in Indian art from the first century AD was the Mithuna or loving couple. Sanskrit texts such as the Agni Purana or the Silpasastras (18) refer to the Mithuna as mangala or auspicious and raksartham-varanartha, protective-defensive. The Brhat Samhita specifically refers to “obscene figures preventing the temples from being struck by lightning” (19). Coomaraswamy suggests that the significance of the representation of mithunas lay in the auspicious progenitive significance of “pairs”, an essential feature of all vedic sacrifices (20). Up to the fifth century AD we have archaeological evidence of a variety of terracotta and ivory images of the mother goddess type, (fig 2) and plaques with sexually explicit maithuna imagery (figs. 3 and 4), a continuation of those dating from the second millennium BC Indus valley culture. A further image from the first century BC shows a grotesque dwarf coupling with a female with a ram’s head (21). Many scholars see an interrelationship between the ritual practices of the Indus Valley and Vedic Brahmanism (22). Archaeological evidence from Harappa relating to generative iconography can be seen on a seal depicting a female figure with a lotus stem emerging from her vulva (23) or the sexual union of a buffalo and a woman, themes such as the worship of the Lajja Gauri fertility symbol from the third century AD (24). Donaldson refers to the importance of the female in agricultural societies where naked women served as sowers of crops and brought rain in time of drought (25). Doris Srinivasan describes the burial of a hermaphrodite pot with male organ and female breasts beneath vedic sacrificial altars as a generative totem (26). The emphasis on fluids in the Kaula tradition may have its origins in the ritual pre-eminence of water suggested by the archaeological evidence of the central bath in Harappan cities (27). Figure 5 provides further archaeological evidence of the continued important link between water and the goddess in a ritual terracotta tank with goddess and shrine attributed to the second century BC. Can we establish a link between the generative iconography of the ancient Indus Valley culture, the magico – protective mithuna and maithuna images from the second century BC and the transmutation of fluids referred to in seventh century north Indian Kaula Tantric practice?

From the fourth century BC to the fourth century AD, there was in North India an expanding urban population and an increasingly prosperous merchant class. Extensive Buddhist pilgrimage resulted in a trade of goods and ideas. The emphasis on gifts given in exchange for spiritual merit developed into community patronage (28). There is growing evidence of this in large-scale Buddhist viharas and stupa sites. An image on the ceiling of cave 17 at Ajanta dating from the fifth century AD is an early example of this growing sensuality (fig. 6). Mithuna images appear on ceilings or on the thresholds of these viharas. Concomitant with this patronage of Buddhist sites, there is archaeological evidence (fig. 7) of the growing popularity of cults of Dionysiac type. Urban affluence encouraged the fashion for sringara, a taste for sensuality and its depiction. The continued use of the mithuna motif as a magico-protective device can be seen in the early sixth century cave of Badami (fig. 8) and the earliest surviving sixth century temples of Orissa, from the Sailodbhava period, although they are small in size and appear in subsidiary niches.

From the fourth to the seventh centuries there was a gradual reduction in city populations due to the decline in the popularity of Buddhism and the trade associated with Buddhist pilgrimage (29). There was a regeneration of magico-religious beliefs through the infiltration of Tantrism. Patronage ceased to flow from wealthy townsmen who were replaced as sponsors by feudal chiefs (30). These warrior chiefs severed links with the towns and drew their wealth from the land rather than trade. This brought about a decline in devotional cults (bhakti) and led to a ruralization of the ruling classes. These chiefs made relations with local tutelary deities, particularly clan goddesses (31). This was reinforced by Brahmanical colonization of tribal areas through the process of land grants (32). In the seventh to eleventh century these Tantric ideas and practices were so compelling that they won the adherence of some of the great royal houses of the period such as the Somavamsis, Chandellas and Kalacuris, whose kingdoms stretched across the Vindhya range and beyond, from Rajasthan to Assam (33). From the ninth century onwards there was a consolidation of power and a rise in artistic patronage in the great courts of the Palas, Rashtrakutas and the Pratiharas – from the tenth to the thirteenth century under the independent dynasties of the Chandellas, Chedis, Cholas and Chalukyas and their feudatories.

During this time, the temple became a feudal organization, the centre of society, with an amassed wealth as a result of donations, included in the celebration of festivals the staging of dance dramas and the reciting of the Puranas and other texts. Tantrism infiltrated temple ritual and feudal courts. This inspired architects to elaborate and prescribe complex designs. These were referred to in Silpa canons such as Virahamihira’s Brhatsamhita and in texts such as the Matsya Purana, and the Vishnu Dharmottara Purana, etc (34). The Brhat Samhita prescribed that mithunas together with creepers, ganas and swastikas should decorate the temple door (fig. 9):

“A door consisting of three, five, seven or nine sakhas (posts or bands in the frame on each side) is highly commended. Now, one-quarter of the door-jamb height at the bottom should be occupied by the two figures (one on each side) of door-keepers. The remaining space should be ornamented (in several of the bands) with the carvings of auspicious geese, auspicious tree motifs, Svastika, Full vases, Mithunas, foliated scrolls and dwarfish figures.” (35)

By the ninth century, small scale mithuna couples became commonplace, often placed on the surrounds of the temple door or on the plinth above the threshold of the sanctum. Protection from demonic forces was obtained not only by mithuna or maithuna imagery but also by various forms of Tantric practice. The growth of prosperous and sophisticated courts gave rise to court drama, literature, and a highly elaborate use of language. Double meaning (sandhyabhasha) and punning (slesha) were as popular as the glorification of bhoga seen in secular texts such as the Kama Sutra. The sophistication of the newly introduced Tantric ideas and magical practices, such as use of the mandala, yantra and the chanting of mantras, was matched by sophisticated linguistic games requiring knowledge of their multiple and layered meanings: a concept repeated in the double-entendres of visual language. Sculptors and men of letters replied to each other’s puns (36).

Fig 11

Erotic imagery became commonplace as a part of the iconography of temples inspired by Tantrism, where the beliefs and tastes of the patron or warrior chief came into partnership with Brahmanic temple requirements. Small scale mithuna imagery remained, used as an apotropaic device on doorways or sanctum thresholds (see fig. 10), Sachiya Mata temple from the ninth century. Larger in scale and more complex are those seen in the tenth century Rajarani Temple and other temples at Bhubanesvar (fig. 11) or the Laksmana (Vishnu) temple, built in 954 AD (fig. 12). Other examples are the Vishvanatha (Siva) temple built in 999 AD and the Kandariya Mahadeo (Siva) temple built in 1030 AD (fig. 13) at Khajuraho. Under the patronage of the Chandella Rajput kings, their feudatories and Jaina ministers as many as 25 temples between 900 and 1150 were constructed at Khajuraho.

The Lakshmana, Vaishnava and Kandariya Mahadeva temples (fig. 14) in Khajuraho possess a variety of erotic sculptures (see figs. 12 and 14). Interpretations offered regarding these sculptures have been varied and fanciful. Krishna Lal argued that the images were there to induce the war-torn and decimated populace “to indulge freely in both explicit and obscene sexual poses… so that soldiers should be available to the king” (37). Danielou wrote that they were touchstones by which the man of renunciation can test if his will to chastity is genuine (38). More philosophical in its interpretation is the idea that the maithuna represented the union of the individual and the world soul, or supreme bliss (39). Other suggestions include the sexual education of the young, initiation of young brides, representations of ritualistic orgies or yogic postures, erotic activities of devadasis or courtesans – more banally implemented to attract people to the temple – or just representations of human activity (40).

More recent studies suggest that this sculpture owes its existence to the growing influence of Tantrism during the early medieval period. According to some scholars, the sculpted depictions of naked ascetics engaged in sexual activity on Orissan eleventh century temples (see fig. 14) and those sculptures seen on the lower level of the Laksmana temple in Khajuraho are evidence of the Kaula-Kapalika cults, powerful throughout India from the eighth to the eleventh century particularly in the areas around Khajuraho and Bhubaneshwar (41). Other scholars such as Desai argued that images on the tenth century Lakshmana temple at Khajuraho are not the expression of an extreme Kula Kapalika Tantric sect but of a moderate Siddhanta sect – a sect which reconciled Tantric with Brahmanic world views. Desai suggested that the figures did not depict the usual extreme practices expected in goddess worship associated with the left-handed Tantric sects. As evidence of this, she refers to the depiction of a Ksapanaka (one of the left-handed Tantrics), engaged in oral-genital relations on the lower plinth of the Lakshmana temple (see fig. 12). She argued that this was a practice condemned in the Sastras and even ignored in the otherwise explicit Kama Sutra and that this image was an illustration from a popular play of that period which mocked extreme sects such as the Kapalika and Kaula sects. She refers to an inscription on the south wall of the Lakshmana temple, below an image of a man engaged in bestial practice, which refers to a “Sri Sadhanandi Khanaka”, the name of a character in a local play possibly a prototype of Krishna Misra’s allegorical play the Prabodhacandrodaya. (fig. 15). This play, popular in the time of the Chandella kings in the eleventh century, supported the orthodox Vedic order, Upanishadic teaching and Vishnu-Bhakti and mocked the non-vedic sects of the Kapalikas, Kshapanakas and Vajrayana Buddhists. This evidence strongly supports the view that the temple patrons were opposed to extreme Tantric rituals (42).

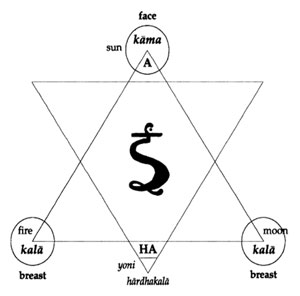

In addition to the scenes on the lower level of the Laksmana we find further images with a more refined, less explicit sensuality on the higher levels of the Vishvanatha temples and on the Laksmana temple. Here we see a swaying beauty and cadence in the ecstatic union of the figures. An example on the Laksmana temple is a standing man and woman in an embrace (fig. 16). A further depiction is one with a man standing on his head engaged in coitus with a woman, who is supported by two attendant figures (fig. 17). The interpretation of figures 14 and 17 is controversial. The diagram which most closely allies with the composition and arrangement of these figures is known as the Kamakala Yantra (43).

Fig 18 (43)

A ninth-twelfth century AD text called the Silpa Prakasa may well hold the key to the interpretation of this complex maithuna image. The Silpa Prakasa manual on Orissan temple architecture was discovered by Alice Boner and Sarma in the twentieth century. The manual signed by Ramachandra Kulacara identifies the author as a left-handed Tantric (44). The text refers to the construction and consecration of the temple. It refers to placing various yantras in the foundations, below various other parts of temples, beneath or behind sculpted images and statues since the Kamakala Yantra, concealed by a love scene, was compulsory on temples dedicated to Siva or Rudra. The manuscript also states that the jangha wall should be subdivided into a number of horizontal sections, one of which, known as the kama-bandha, should display love scenes (45). (see figs. 10 and 20)

“The evil spirits will flee far away at mere sight of the yantra…

In the best temples dedicated to Sakti and to Rudra, this yantra must certainly be placed.

Then the monument will stand unmoved forever… this yantra is utterly secret, it should not be shown to everyone.

For this reason, a love-scene had to be carved on the lines of this yantra… the kamabandha is placed there to give delight to people”

Silpa Prakasa 2.535, 538-9

According to Desai and White the text interprets the form of the Yantra describing how in figure 18 Siva symbolizes the upturned triangle, Sakti his consort the downward pointing triangle. Other details refer to the Sanskrit grapheme A at the apex of the upward triangle with the sun and the mouth of the maiden, while the two breasts of the maiden at the two base angles of this triangle are identified with the fire and moon. Located between these two and pointing downward is the apex of the downturned Sakti triangle, which is the yoni of the maiden and the locus of the grapheme HA (46). The yogic tradition and the silpa text imply that female or serpent energy, which dwells in a tightly coiled form known as kundalini in the lower abdomen, can be awakened through yoga, breath, deep meditation and the power of certain vibrations in the form of mantras. The result of this awakening is a rise of the kundalini or Sakti which is believed to unite with male energy or in the cranium or ajna cakra behind the eyebrows.

Fig 10

In the conclusion to her interpretation of the erotic imagery on the walls of the temples of Khajuraho, Desai argued that the Sutradhara (priest/architect) of the temple expressed the highly structured Vaishnavite metaphysical order in the Lakshmana and the Saiva Tantric system in the images and their placement in the scheme of the Siva Kandariya Mata temple. She goes on to conclude that the architects deliberately chose erotic motifs to act as a coded language, sandhya bhasha. This concealed the yantra from non-initiates but had profound significance to Tantric practitioners; the king himself and his subjects. Desai’s conclusion that the patron belonged to the right-handed variety of Tantrism has however to be seen in the context of left-handed Tantrism. The text of the Silpa Prakasa, which shed such light on the significance of the Kamakala yantra was written by a left-handed Tantric of the Kula clan. The use of a Kaula image on a temple which otherwise exhibits evidence of the right-handed sympathies of the patron reveals the difficulty of making any sharp division between left and right in our interpretation of this imagery. Perhaps the Kamakala yantra can be likened to the right-handed Tantrika who professes to be orthodox while secretly practicing the old ways and can be understood by the initiate and the outsider on various levels of sophistication and understanding.

The sexual exchange of fluids and their refinement within the body described by the Silpa Prakasa, a process visualised in the kamakala diagram, involves an evolution of substances as they pass through the spinal channels to the head of the practitioner. Like Hindu alchemy this may be expressed as the permeation of the denser with the finer, or in other words a material grading of bodily substances and a ladder of consciousness (47). Similarities can be seen between the alchemical refinement of mercury and other metals and the transmutation of the man in his own material body. “The body stripped of impurities becoming denser, shining and immortal perfected hard as a diamond” (48). In other words, the finer is believed to have the potential of permeating the dense matter until it becomes immutable, capable of blending with the highest level of vibration. Texts such as the Atharvaveda refer to a physiological chemistry of the body in which there are numerous references to the effect on the relationship between vital processes and breath or prana, the latter seen in an ancient knowledge of breath control, where states of mind were evoked by mantras. These were thought to assist the focus of attention and reinforce the link between breath and a man’s soul or Brahman (49). We see a digestion of substances, a spiritual biology with the assistance of heat, yogic breathing, the vibration of sound, in other words a complex transmutation of inner invisible energies. The body is seen as a crucible or temple for this process, requiring in Kula or Kaula Tantra the introduction of female fluids for effective transformation. In the twelfth century practices involving sexual fluids were replaced in some cults by abstract concepts, perhaps inspired by Buddhist logic. This earlier practice defined by the use of mantras and breath, sexual orgasm or bliss as an end in itself was replaced by the expanded awareness of the vibration of sound towards silence and the experience of a higher level of consciousness. In other words it might be expressed as the subtler to the subtlest, the denser to the densest in the individuation of the soul (50).

Conclusion

Archaeology revealed the earliest use of explicit sexual imagery in the Indus Valley civilization from 1500 BC, an urban culture dependent on agriculture. These erotic figures were found beside a large number of female goddess images, suggesting fertility magic or protection. Reference to the magico-protective function of the mithuna/maithuna imagery was also seen in texts such as the Agni Purana and the Brhat Samhita. From the second century BC mithuna imagery appeared on thresholds of Buddhist viharas and stupas and some terracotta plaques. Scholars have suggested that these images may be generative by virtue of their being sexually explicit. From the seventh century onwards, there was an increase in the infiltration of Tantrism on ritual and architecture in temples and in the feudal courts of India. In addition to the absorption of certain Tantric practices there were a growing number of Tantric practitioners, engaged in secret practices outside the mainstream of Hindu society. Kula Tantra was an early form of Tantric practice. There was a rise in the number of yogini temples and worship of the goddess became rapidly more widespread and popular. Clear parallels were revealed between Hindu alchemy and the Tantric refinement of bodily substances.

Through the Puranas which assimilated Tantric elements, Tantrism penetrated temple rituals. From the eighth century onwards, Tantric ideas also began to inspire courtly drama and literature mostly notably the Kama Sutra. In the twelfth century Abhinavagupta, perhaps inspired by Buddhist logic and monastic discipline, reformed Tantric practice and revised its concepts.

Tantrism, now known as right-handed practice, became a celibate discipline, still however involving breath control, mantras and visualisation. The practitioner aimed at a subtle permeability in mind and body not just to achieve magical powers and immortality, but in order to realise the highest power of the cosmos. The goal of right-handed Tantrism was the realization through direct knowing of what had been the object of knowledge, or in other words the withdrawal of the manifest into the non-manifest.1 Brahman and Atman were still related, however, God was no longer perceived only as the divine nectar or Sakti, but as a refined and heightened awareness. God was no longer moving in the waters, but beyond the earth and in the stars.

Unlike western attitudes in the nineteenth century, we are closer today in understanding the purpose of the maithuna and mithuna’s own temples such as those in Khajuraho. We might grasp the significance of the sexual act as union, delight in the sensual or even understand the fear of the spirit world from which they sought protection. However, it is much more difficult to understand the intention of the complex sexo-yogic Tantric imagery from the great monuments in Orissa or Central India. Secrecy was perhaps the aim of the craftsmen. The concealment of meaning was essential to fulfill the purpose of experiential initiation. Perhaps the craftsmen chose to portray a sensual image which would both delight and dissemble thereby protecting the secret formula from the uninitiated.

To sum up: what does the development of erotic imagery tell us of the attitude to the body in India? Despite a long tradition of live offerings, knowledge of dissection and anatomy was apparently non-existent until after the third century BC.2 What was surmised in the body as subtle channels or veins on either side of the spine was intuited and imagined together with a belief in a complex hierarchy of the ingesting of substances and their potential to prolong and provide life. This transmutation of energies was also applied to the science of alchemy in India. Alchemical practices related not only to metals but also to the evolution of the human body and soul.3 In ancient India one can observe a specialized knowledge of the body developed alongside ascetic practices.4 In Tantrism man and god were likened to metals in their potential for transmutation. Man was believed to become transformed, become identified with, absorbed by, permeable to the divine through the transforming nature of consciousness. In other words the soul (atman) and God (Brahman) were somehow on a certain level material and realisable.

The understanding of erotic sculpture involves not just the ability to read the relevant texts or the imagery but to directly experience and envision this inside oneself. Hinduism teaches the West not to turn our eyes to heaven to search for God, but to look and listen to our own bodies and inside the silent places of our minds. If this is possible, what the sculpture reveals would be sensed, the invisible seen, unity experienced. To understand the significance and meaning of the mithuna images requires in the Western audience an openness to double meaning and an acceptance of the juxtaposition of the obscene and the sublime. One must dissociate sin from sexuality and see rather that bhoga –enjoyment- is a form of yoga– union, or in other words: the dissolution of the boundaries between the phenomenal and the numinous in the experience of the bliss of sexual union. One needs to know the experience of a place beyond ordinary time, a place which is silent, clear, still and yet with a quality of vibration, a journey through breath, pulse, heat, intensity and the light of the inner union of energies.

Notes

(1) The Svetatasvatara Upanisad and the Chandogya Upanisad date from the middle and early first millennium BC. See also D. Lorenzen: 2002, 27.

(2) D White: 2000, p. 9; also D. White, 2003, 1-26.

(3) G. Flood: 2006, 9.

(4) T. McElvilley: 1981, 47-48; The interpretation of this seal is however highly controversial. See D. Srinivasan “Unhinging Siva from the Indus Civilization”Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, No. 1 (1984), 77-89.

(5) D. White: 1984, 46. This is known in the alchemical case from the descriptions of the places in which various elements were to be found and because of the fact that many such elements (such as cinnabar) only exist in these mountainous regions. In the Tantric context, it was in the same regions that the pilgrimage sites peculiar to these sects were to be found.

(6) Bhairava’s consort (Aghoresvari, Uma, Candi, Sakti).

(7) D. White: 1998, 190-191.

(8) D. White: 1997, 77.

(9) D. White: 2000, 12.

(10) T. McEvilley: 1981, 56-58.

(11) D. White: 1998, 174 “This eleventh-century development was Tantra (Srividya Kaula a highly semanticized version) a religion of dissimulation”: text – the Yonitantra 4.20 in JA Schoterman ed., 1980.

(12) H. Elgood: 1999, 105-6; T. Donaldson: 1975, 88.

(13) P. Mitter: 1977, 1-2 and 9-10.

(14) P. Mitter: 1977, 2 and 105.

(15) P. Mitter: 1977, 180-183.

(16) J. Keay: 1981, 99.

(17) P. Mitter: 1977, 271.

(18) Scholars date these texts approximately as fifth to sixth century AD although they doubtless include earlier oral traditions.

(19) U Agarwal: 1968, 260, also cited in T. Donaldson: 1975, 93 fn 81.

(20) T.P Bhattacharya: 1967, 49; Coomaraswamy, Yakshas, Washington, 1928, 30 cited by T. Donaldson: 1975, 93.

(21) N. Ahuja: 2001, (fig. 3.272) see list of illustrations.

(22) A. Parpola: 1993 ; B. Sergent: 1997, 121-23.

(23) N. Ahuja: 2001 (fig. 3.276), Woman giving birth to vegetation. Chandraketugarh 1st century BC – 1st century AD. Private collection, London.

(24) Lajja Gauri refers to the Goddess with spread legs and a lotus instead of a head, worshipped as a fertility symbol. D. White: 2003, 28.

(25) T. Donaldson: 1975, 85 fn 35 cites W. Crooke: 1926, 71.

(26) Elgood in S. Mittal and G. Thursby ed., 2008 7; D Srinivasan: 1997, 190.

(27) A. Parpola: 1993, 9 and 179.

(28) R. Thapar: 1987.

(29) R.S. Sharma: 1983, 105-157also see R.S. Sharma: 1987.

(30) D. Desai: 1990, 7.

(31) L. Harlan: 1992, 10-12.

(32) D. Desai: 1990, 8 fn. 30.

(33) D. White: 1998, 198.

(34) D. Desai: 1990, 21.

(35) Brhatsamhita 56, 14-5.

(36) D. Desai: 1987, 384, and see D. Desai, 1990, 26. According to Desai the earlier Vishvanatha temple mentions its sutradhara Chhichha by name who was “well versed in visvakarmasastra”. Desai argues that these sastras as well as the Pancharatra texts are more detailed regarding the placement of images than the Vastu or Silpa texts.

(37) K. Lal: 1967, 63.

(38) A. Danielou: 1948, 88.

(39) F. Leeson: 1965, 31.

(40) T. Donaldson: 1975, 75-100.

(41) T. Donaldson: 1975, 76.

(42) D. Desai: 1984, 149-151.

(43) A. Avalon: 1961.

(44) A. Boner and S.R. Sarma: 1966, vii. Some claim this is a pastiche of medieval manuscripts and that there was no single manuscript entitled Silpa Prakasa, however the scholars Thomas Donaldson and Devangana Desai continue to accept the authenticity of this source in their writings.

(45) D. White, 1998: 186-7. Jangha wall is a “pilaster-like projecting wall-element between two chamfers, reaching from the pancakarma to the upper bandhana illustration in Boner and Sarma: 1966, 147.

(46) D. White: 1998, 178 cites fn. 17 KKV verse 25a.

(47) D. White: 1984, 51.

(48) D. White: 1984, 54-57.

(49) K. Zysk: 1993, 202 citing the Atharva Veda (AV 15.11.5, 14.11)

(50) D. White: 2000, 16 cites A. Sanderson: 1988, 679-80.

(51) A. Avalon: 1961.

(52) K. Zysk: 1986, 691 “The evolution of Anatomical knowledge in Ancient India, with Special Reference to Cross Cultural Influences” in Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 106, No 4 (Oct – Dec, 1986), 687-705.

(53) D. White: 1984, 67-68.

(54) N. Ziegler: 1973, 77-78.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

» U. Agarwal, “Mithunas: Why Obscene ‘Sculptures?” Oriental Art XIV, 1968

» N. P. Ahuja, Early Indian moulded terracotta: the emergence of an iconography and variations in style, PhD Thesis, SOAS, University of London, 2001.

» J. N. Banerjea Pauranic and Tantric religion, Calcutta, 1966

» T.P Bhattacharya, “Mithuna figures in Indian art”, Lalit Kala XIII , 1967

» W. Crooke, Religion and folklore of Northern India, London, 1926

» A. Daniélou “An approach to Hindu Erotic sculpture” Marg 11, 1948

» D. Desai, “Placement and Significance of Erotic sculptures at Khajuraho”, in Discourses on Siva, ed. Michael Meister, Philadelphia, 1984

» D. Desai, Erotic Sculpture of India – A Socio-Cultural Study. Second edition 1985.

» D. Desai, “Social Dimensions of Art in Early India”, Social Scientist, Vol. 18, No.3 March, 1990, 3-32

» D. Desai, The Religious Imagery of Khajuraho, Mumbai: Franco-Indian Research Pvt. Ltd., 1996

» D. Desai, “Puns and Intentional Language of Khajuraho” in Kusumanjali: new interpretation of Indian art and Culture: Sh. C. Sivaramamurti commemoration volume, ed. M.S. Nagaraja Rao, Delhi, 1987 383 – 389

» T. Donaldson “Propitious-Apotropaic eroticism in the art of Orissa”, Artibus Asiae, vol 37, 1975, 75-100

» T. Donaldson, “Erotic Rituals on Orissan Temples”, East and West 36, nos. 1-3 Rome, September, 1986, 137-182

» H. Elgood Hinduism and the Religious arts, Cassells, London, 1999

» H. Elgood in ed. S. Mittal and G. Thursby Studying Hinduism: Key concepts and methods. Routledge, 2008, 3-18

» G. Flood, The Tantric Body: The Secret Tradition of Hindu Religion, I.B. Tauris, London, 2006,

» L. Harlan, Religion and Rajput Women: The Ethic of Protection in Contemporary Narratives, (University of California Press) 1992.

» Kama-kala-vilasa by Punyananda-natha with the Commentary of Natananda-natha, 3d ed., trans. With commentary by Arthur Avalon (Sir John Woodroffe) (Madras: Ganesh & Co., 1961 .

» K. Lal, Miracle of Konarak, New York ,1967, p.63

» S. Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, Calcutta, 1946

» D. Lorenzen, Kapalikas and Kalamukhas: Two lost Saiva sects, Delhi: Thomson, 1972

» F. Leeson, Kama Shilpa, Bombay, 1965

» D. Lorenzen “Early Evidence for Tantric religion” in ed. K.A Harper and RL Brown The Roots of Tantra, 2002

» J. Keay, India Discovered. The Recovery of a Lost Civilization, Harper Collins, London, 1981

» Y. Krishan. “The Erotic Sculptures of India”, Artibus Asiae, XXX1V, 4, 1972, 331-343

» T.McEvilley “An Archaeology of Yoga”, RES:Anthropology and Aesthetics, No 1 Spring, 1981, 44-77

» P. Mitter. Much Maligned Monsters: History of European reactions to Indian art Oxford: Clarendon, 1977

» A. Padoux: Vac: The Concept of the word in selected Hindu Tantras. Suny Press, 1990

» A. Parpola, Deciphering the Indus Script, Cambridge University Press, 1993

» A. Sanderson, “Saivism and the Tantric Tradition” in The World’s Religions, ed. S. Sutherland et al. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1988, 669-79

» A. Sanderson, “Meaning in Tantric Ritual” in Essais sur le ritual, vol.3, Colloque du Centenaire de la Section des Sciences Religeuses de l’Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, ed. A. Blondeau and K.Schipper, Louvain and Paris : Peters, 1995

» J.A. Schoterman,ed. and introduction the Yonitantra , Delhi, Manohar 1980

» B. Sergent, Genese de l’Inde, Paris: Payot & Rivages, 1997

» R.S. Sharma Perspective in Social and Economic History of Eary India, New Delhi, 1983, 105-157

» R.S. Sharma Urban Decay in India (c. 300-c. 1000), New Delhi, 1987

» Silpa Prakasa: Medieval Orissan Sanskrit text on temple Architecture by Ramacandra Kulacara, trans. and annotated by Alice Boner and Sadasiva Rath Sarma, Leiden; Brill, 1966

» D. Srinivasan Many heads, arms, and eyes: origin, meaning, and form of multiplicity in Indian art. Brill, 1997

» D. Srinivasan “ Unhinging ?iva from the Indus Civilization”Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, No. 1 (1984), 77-89

» M. Strickmann Mantras et Mandarins: le bouddhisme tantrique en Chine Paris : Gallimard, 1996

» The Tantraloka of Abhinavagupta with the Commentary of Jayaratha, ed. R.C.Dwivedi and N. Rastogi 8 vols. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1987

» R. Thapar, Ancient Indian Social History, New Delhi, 1978,

» D. White, “Why Gurus are Heavy”, Numen, Vol. 31, Fasc. 1, July, 1984, 40-73

» D. White “Mountains of Wisdom: On the Interface between Siddha and Vidyadhara Cults and the Siddha Orders in Medieval India”, International Journal of Hindu Studies, Vol. 1, No 1, April, 1997, 73-95

» D. White The Alchemical Body, Siddha traditions in Medieval India, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996, reprinted New Delhi:Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 2004

» D. White “Transformations in the Art of Love: Kamakala Practices in Hindu Tantric and Kaula traditions” History of Religions, Vol 38, No.2, November, 1998, 172-198

» D White, Tantra in Practice, Oxford: Princeton University press, 2000

» D. White, Kiss of the Yogini: “Tantric sex” in its South Asian contexts, (Chicago, Ill.: London: University of Chicago Press, 2003

» D. White, Sinister Yogis, Chicago; London: The University of Chicago Press, 2009

» D. White, Yoga in Practice, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2012

» Yonitantra 4.20 in JA Schoterman,ed. And Introduction to the Yonitantra Delhi: Manohar, 1980

» N. Ziegler , Action, Power and service in Rajasthan culture: A social history of the Rajputs of Middle Period Rajasthan. PhD Dissertation, Chicago. Submitted in August 1973.

» K. Zysk, “The evolution of Anatomical knowledge in Ancient India, with Special Reference to Cross Cultural Influences” in Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 106, No 4, October – December, 1986, 687-705

» K. Zysk, “ The Science of Respiration and the Doctrine of the Bodily Winds in Ancient India” in Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 113, No 2 , April – June, 1993, 198-213

List of Illustrations

» Click here to see all the illustrations

1) Indus Valley Seal 1750-1500 BC “Cross-legged masked Figure” National Museum of Delhi

2) Enshrined goddess with 10 Ayudhas and attendants. Chandraketugarh 1st century BC (26.7 x 20 cms) Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (1990.281) also cited N. Ahuja N. P. Ahuja, Early Indian moulded terracotta: the emergence of an iconography and variations in style, 2001. (fig 3.187)

3) Maithuna image on terracotta panel. Chandraketugarh 1st BC (5×4 cms). Private collection. Also cited N. Ahuja (fig 3.25)

4) Maithuna couple Chandraketugarh (5×4 cms) Private collection. Also cited in N. Ahuja (fig 3.262)

5) Ritual terracotta tank with Goddess and shrine (cited in Marshall: 1951: pl 136, fig 158) and N. Ahuja, op.cit (fig 3.2) The British Museum (11.12×11 inches)

6) Mithuna couple in ceiling painting. Ajanta cave 1. ca 468AD

7) Mithuna couple dancing on red sandstone vedika railing, Mathura 1st century AD.

8) Mithuna couple in ceiling on cave temple of Badami, 578 AD

9) Mithuna couples ornamenting doorway of Gupta temple of Nachna Kuthara, Madhya Pradesh early 6h century AD

10) Maithuna couples engaged in sexual intercourse, a small panel above the shrine threshold, Sachiya Mata temple, 9th century, Osian, Rajasthan.

11) Maithuna couple engaged in sexual orgy, Rajarani Temple, 11th century Orissa.

12) Couples engaged in sexual orgy, lower plinth Laksmana temple, (954 AD) Khajuraho

13) Kandariya Mahadeo temple, (1030 AD) Khajuraho

14) The upper wall of the Kandariya Mahadeo temple, Khajuraho

15) The male committing bestiality with the horse, lower plinth, Laksmana temple, Khajuraho.

16) The upper level of the Laksmana temple, Khajuraho

17) The Kamabandha wall with the figures engaged in the sexual act of intercourse

18) The Kamakala according to Yoginihrdaya 2.21 illustrated in D. White “Transformations in the Art of Love: Kamakala Practices in Hindu Tantric and Kaula traditions” History of Religions, Vol 38, No.2, November, 1998 179

19) The Kamakala yantra according to Silpa Prakasa 2.508-29

20) Jangha of the ca. 1000 AD Kandariya Mahadeva temple at Khajuraho with the Silpa Prakasa kamakala superimposed on it. The image is found in Devanagana Desai, The Religious Imagery of Khajuraho (Mumbai: Franco-Indian Research Pvt, Ltd., 1996), p. 195.

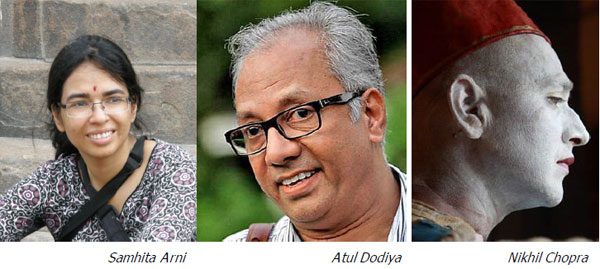

SHARPENER OF SOULS by Aveek Sen

A version of this article was first published in The Telegraph, Calcutta, on March 9, 2014

Study for Metamorphosis of Narcissus, by Salvador Dalí

Conversations, those that remain, are of three kinds, I used to think.

First, the ones you have sitting by flowing water. Think of Benaras conversations on October afternoons, when the buffaloes come to bathe in the river. The langots and linen drying on the ghat blow about in the breeze, and Manikarnika seems to have burnt itself down to a few well-done whiffs. As you half-gaze at the water and talk, you begin to notice that it does not quite flow in a single direction. At different places on the river, there are pools of fine chaos making complicated weaves as depths and surfaces pull in different directions. And if you gaze long enough, and wide enough, at these patterns, it is possible to think that the river is not moving at all, but the ghat is — in tiny, barely perceptible shifts that make you feel slightly, ever so slightly, dizzy. It is as if with each such movement, you sense for a split second the Earth’s rotation. It is at such moments that the flow of talk, its deeps and shallows, twists and spirals, start becoming indistinguishable from the movement of light on the face of the person you are talking to, and from that dim half-sense of time passing yet not passing, the river flowing yet not flowing.

Then, there are conversations by still water. I remember one at sunset, sitting by an immense reservoir of stone, filled to the brim with water, in the vast, ruined compound of a great temple. There was a half-submerged minaret in the middle of the water, which looked as unreal as it was unreachable. There were giant boulders all around us, their power to destroy indefinitely suspended. There is something immeasurably ancient, almost pre-temporal, about the combination of still water, rocks and stone, especially if the water happens to be clear. It has to do with being able to see straight down to the bottom, but through the reflection of the sky on the surface. This is a visual realization of depth, of height held inside depth, which lends itself to comparisons with the way we imagine the human mind — with reflection, in the other sense.

But here, too, if we look long enough, and close enough, we realize, as we begin to make out the little ripples on the surface of the water, that what we are looking at is not stillness, but a ‘moving still’. And the words spoken beside the still waters, as the psalm puts it, have to make room for distance and silence, the gifts of trust.

Once, during a particularly irritating junket tour, rattled by my fellow travellers and exhausted by continual sightseeing, I found myself inside a 50,000-year-old limestone cave. Walking about listlessly in its echoing dankness, and trying to tell the stalactites from the stalagmites, I turned a corner and, all of a sudden, opening up in front of me was an enchanted world that took my tiredness away in a trice. I was in an eerily lit grotto of strange rock-forms and clear spaces that came together to create a magical effect of two-tiered replication. Then, in that subterranean stillness, one of the stalactites let fall a single drop of water, and the widening ripples on the surface of where it fell suddenly made me realize that one half of that miracle of symmetry was a reflection in water, the illusion now shattered by the droplet, but already beginning to form again. I had lost the others by then, and as I lingered in the slow time of this glimmering cavern, I watched that mirror being made, unmade and remade over and over again. I stood mesmerized while another memory began to rise up in me: I had seen this pool and these rocks before — this dreamed-up world of precarious doubles. “Dalí, of course!” I must have exclaimed to myself when it came to me at last — the Metamorphosis of Narcissus.

Finally, there is the sea — which is about the impossibility of conversation. The person who understood best the sea’s sublime indifference to human laments or chatter was, of course, Fellini. Only three of his creatures manage to resist being reduced to nothing by the sea; none of them speaks, and only one of them is human. Saraghina, with her thunder thighs and flashing eyes, dances her wordless, immortal rumba on the beach for the truant schoolboys of 8½. But she is more force of nature than woman — like one of those Big Bang giantesses in the Cosmicomics by Fellini’s countryman, contemporary and kindred soul, Calvino. Yet, as the children are chased back by their killjoy masters against the shimmering backdrop of the sea, the roaring of the waves drowns that Siren-music and the children’s cries; and the only creature to survive the sea-changed funeral party in E la Nave Va — And the Ship Sails On — is a mute, lovesick rhino in a lifeboat.

But the greatest conversation-stopper in Fellini is the monstrous jellyfish, with its deathly, one-eyed stare, that is heaved out of the sea at the end of La Dolce Vita. All the desperate talk in the film, serious and unserious, must end up at the edge of this sea, where, suddenly, an angelic young waitress from an earlier scene returns, like a promise of redemption, only to give up on trying to say what she wanted to say to Marcello across the endless watery flats of the beach. They are too far away from each other, and the sea too loud, for her to be heard. Marcello’s gesture to her — somewhere between a wave, a shrug and a sigh — is like a last toast raised in mock-helpless exasperation to the grand futility of human attempts at communication.

I thought I had worked out my own taxonomy of conversations, until, a few months ago, I met up with a loquacious and long-lost friend in that exquisite old city of the nawabs. The Gomti is too smelly for conversation. So we climbed up to one of the upper storeys of the Bara Imambara, and sat in an arched alcove on the terrace all day, looking out on the city with the Bhulbhulayah behind us. And it occurred to me then, surrounded by austerely errant Islamic-Rococo, that I would have to invent yet another category for a conversation that fitted none of the other kinds — the conversation beside a labyrinth.

We are so used to thinking of a labyrinth as metaphor, or as fictional device or setting, that it is unsettling to be actually confronted with one. So, as we sat in front of a real labyrinth and did our catching-up, the genius of that elaborate folie began to control our sense of what we called, rather grandiosely, “the intrigue of life”. Like the maze of passages and stairways behind us, everything began to connect with everything else in a treacherous half-light that prevented us from knowing for sure whether the patterns we saw, and helped each other see, were real or just figments of talk. We gazed, as we spoke, at Lucknow’s many domes, each a little different from the other, one of them changing from ivory to grey and back to ivory again as the sun went in and out among the swiftly moving cloud-forms. It was as if all of Calvino’s Invisible Cities were gathered in a single, semi-substantial skyline.

What made us descend from those heights to the streets below was hunger. As we made our way towards the heady aroma of burning flesh — which I tried not to connect with those autumnal whiffs from Manikarnika — we came upon a scene that flashes upon the inward eye, and tortures the inward ear, as I try to order my thoughts on the afterlife of conversations. We heard the unbearable sound of metal being sharpened against metal — possibly the most inhuman noise that human beings can produce, antithesis of the voice. Then, as we turned into an alley, we saw an emaciated man pedalling away intently on what looked like an antique but stationary bicycle. The pedalling caused a large wheel fixed to the front of the contraption to rotate. He held a long knife to the edge of the wheel, and even when it shot a constant shower of sparks at his eyes, together with that high metallic hiss, his gaunt, almost cruel, face remained perfectly still, and the knife in his hands began to glint more visibly in the failing light.

“A sharpener of knives,” I said to my friend. And the man’s unmoving concentration on his task began to turn him into another kind of figure in my eyes. “What if you put yourself in his hands when you feel blunted by the world, so that he gives you back your edge?” I asked my friend, with quickening pulse, “Don’t you need someone like this in your life from time to time?” “You mean a sharpener of souls?” he caught on at once, “I wonder if there’s enough steel in me.”

THE TEMPLE AND THE BODY: DANIÉLOU ON THE VERTICAL AXIS OF EXISTENCE by Adrián Navigante

If we think of a Christian temple, the main aspect of it seems to be a house where an assembly takes place (domus ecclesiae), the assembly of God’s people, of the ones who are called together in order to perform a special cult and strengthen the bond between them and God. The emphasis on this aspect, which dates back to Cyril of Jerusalem’s notion of convocatio (in his Catecheses from the IV century c. E.) and lends itself to parallels with the Jewish tradition (for example in the idea of “synagogue”), has led over the centuries to a neglect of the sacred character of the very building known under the name of “church”. Most probably as a result of this the ex-pope Benedict XVI, in a recent book on liturgy, reminds the reader of the essential distinction between the Christian place of adoration and the temples of other religions, a distinction consisting precisely in this aspect of “assembly of the faithful”, does not reverse or suppress the character of “temple” contained in the very idea of domus ecclesiae (cf. Joseph Ratzinger, Der Geist der Liturgie, 2013, p. 55). In other words: a temple remains fundamentally – and even beyond the peculiarities both of Christian secularization and the secularization of Christianity – the abode of the divine and is therefore to be delimited from the profane processes and actions of everyday life, where the existence of man does not follow a pattern of creativity, dynamic variation and intensity, but rather one of bare repetition, routine and inner enfeeblement.

It is precisely this aspect that Daniélou stresses in his books on the Hindu temple and erotic sculpture in India. After explicitly rejecting the idea of “temple” merely as a place of reunion or assemblage of worshippers, he emphasizes some esoteric aspects concerning not only the purpose of the construction of a temple (“picking up subtle influences”, Daniélou, Le Temple Hindou, 1977, p. 11), but also the living architecture, the symbolic pregnancy and the religious function of it. The architectural essentials consist of geometric figures (yantras and maṇḍalas) that stand for the subtle aspects of the cosmic energy – an energy concentrating itself on specific places (tīrthas, kṣetras, piṭhas, cf. Daniélou, L’erotisme divinisé, 2002, p. 63). However, no architecture can be said to “breathe” or “live” if that which is built proves to be separated from cosmic rhythms i. e. not entrusted in its very roots by a dynamic principle governing the diversity of creation as a whole – since the sacred geometry is not made of abstractions, but of subtle levels of manifestation where the true nature of things (tattvadarśin) unconceals itself. The symbolic pregnancy has to do with the aesthetic counterpart of the subtle tendencies and energies contained in the diagrams of the temple architecture. Taken as counterpart to the subtle dimension, this material layer of manifestation displays faces, names, forms and movements adapting themselves to the rhythmical core of human perception. This is one of Daniélou’s explanations and justifications of Indian iconographic polytheism (for example the presence not only of yantras and maṇḍalas, but also of Śiva, Rudra, Pāśupata, Satī, Pārvatī and Kālī images in different temples). Nevertheless, if we understand by “symbol” that which casts together two orders of being (the immanence of the profane world and the transcendence of the sacred, the immediately perceptible and the intuitive ideational), we can say that the very power of transcendence is contained in the anthropomorphic features of the Indian gods, or even more precisely: that the human-like form of the godhead implies at the same time a divinization of man. As to the religious function, Daniélou points to the connection between universal manifestation and voluptuousness (“The fundamental nature of every existing being is voluptuousness”, Daniélou, Yoga, kâma: le corps est un temple, 2005, p. 132), something which according to him has been misunderstood and distorted by the historical development of religious doctrines, especially since the consolidation of monotheism as a system based on what he calls conventional morality, that is, a morality based for the most part on prejudices and therefore prone to a drastic restriction of the path to self-realization.

Daniélou defines the Hindu temple as a center of communication between two worlds essentially related to each other that nevertheless ignore themselves (Daniélou, Le temple hindou, p. 11). This lack of connection is due to the limited scope of human perception. According to classical Hinduism, the energetic rhythm of creation is ultimately free from the constraints of individuated sense qualities (like sight, hearing, taste, smell and touch); the rhythm of organized energy bound to the crystallization of ego-consciousness (ahaṃ-kāra) implies necessarily a perception detached from the source of all being and life. Scientific research may widen this horizon of experience, but the mode of cognition belonging to it remains relative, relational and fragmentary. In other words: the expansion of knowledge by means of gradual appropriation and manipulation of objects does not change the quality of cognition. In the tradition of yoga there is another mode of knowledge, to which Daniélou devoted not only part of his book Yoga, Method of Reintegration (1949), but also a very interesting essay published in France-Orient under the title Le yoga ou la perception de l’unité (1950). In the latter essay he gives some helpful clues to a proper understanding of this singular dimension of experience. If knowledge based on sense-perception is a distortion of the source and intellectual knowledge only an infinite approximation to it, there is only one way of knowing absolutely: the identification of the knower with the thing known. Identificatory knowledge implies joining oneself to the source of all experiential registers. This process of joining the source does not occur without yoking one’s consciousness to the very center of one’s own being. Both words “joining” and “yoking” correspond to the Sanskrit root yuj-, from which the term “yoga” derives. According to Daniélou, there are sensory and intellectual instruments consciousness resorts to in everyday life, but from which it can also detach itself in order to grasp its very source. The techniques of yoga lead to this accomplishment of knowledge by identification or metaphysical knowledge (sayujyam, vidyā) by purifying the energy centers (cakras) from their sensory, mental, emotional and ideational frames, being each one of these frames a kind of dam preventing consciousness to flow freely, an obstacle to the ultimate reintegration of the One in the many or the ultimate realization of the many as the One. In this sense we can say that the expanded perception of purified consciousness, symbolized in each stage of the gradual ascent of the kuṇḍalinī śakti through the main subtle channel of the body (suṣumṇānāḍī), is an open door to a vertical axis of existence.

The architectural disposition of the chakras pointing and leading to divine union reveals the body as temple, and the transmission belt of the divine is for Daniélou mainly erotic – as indicated by the term mithuna, symbolically related to the union (coitus) of the two fundamental principles in the Saṃkhyā philosophy: puruṣa and prakṛti (cf. Daniélou, Le temple hindou, p. 79). The profusion of erotic iconography that characterizes many Hindu temples can therefore be seen as the symbolic counterpart to the motif of androgyny in various mythological sources. In the Skanda Purāna, where Śiva is shot by Kāma’s arrow, he declares he can find peace (śanti) only with Pārvatī. The solution to sexual desire as lack or deprivation is according to this myth satisfaction instead of chastity. Śiva’s cure to his sexual fever is symbolized in the union of liṅgam with yoni, where the structure of “thirst” (endless repetition of something in the end frustrating, corresponding to the Buddhist term tṛṣṇā) is replaced by a plenum of voluptuous affirmation. According to Daniélou, a passage from one of the primary Upaniṣads provides a cryptic analogy to the myth of Śiva and Pārvatī: “As a man embracing his beloved woman knows nothing within or without, so the one embracing the divine knows nothing within or without” (Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad 4. 3. 21). The message of this passage is that the form of the divine is not purely formal, but the most substantial content providing absolute fulfillment or inner bliss (ānanda) beyond all desire, anxiety and sorrow. Daniélou sees in this passage two levels of desire: the first one is egoistic, possessive and destructive, that is desire trapped in the field of individuated perceptions and mental processes. The second one is the realization of the desirable as an absolute act, an experience of wholeness related to the intensity of the experienced beyond the frame of individual restrictions. As a result of this, Daniélou understands by ānanda “voluptuousness” rather than any kind of (ascetic) bliss. In his book L’erotisme divinisé, he summarizes his view on this subject: “According to the Hindus, sexuality appears as the principal means through which nature keeps us enslaved, but at the same time as an instrument to free ourselves from this slavery” (Daniélou, L’erotisme divinisé, p. 172). The positive or negative character of sexuality is a matter of expanded or restricted perception (symbolized in the number of “awakened” cakras). It all depends on the question whether the body has remained a profane abode or has been redressed to the vertical axis and transformed into a temple. In this sense Daniélou remains faithful to the Tantric equation yoga–bhoga: self-realization or integration through the expansion or divinization of pleasure.