“Without contraries there is no Progression”

William Blake

The ALAIN DANIÉLOU FOUNDATION’s Honorary President, Jacques E. Cloarec,

lights the candle at the Inauguration Ceremony

(Zagarolo, June 22nd, 2013)

Index:

- » The ALAIN DANIÉLOU FOUNDATION’S SUMMER MELA 2013 by David Gimbel

- » IMPRESSIONS OF A SPEAKER AT “THE BODY CONFERENCE” by Joseph S. Alter

- » The ALAIN DANIÉLOU FOUNDATION’S SUMMER MELA IN THE ITALIAN PRESS

- » The ALAIN DANIÉLOU FOUNDATION’S DIRECTOR, ION DE LA RIVA, VISITS EUROPEAN & INDIAN INTERLOCUTORS

- » THE BODY IN INDIAN ART by Naman Ahuja

- » MANY-SIDEDNESS: THE NON-VIOLENCE OF THE MIND by Aidan Rankin

- » WHICH HINDUISM? ALAIN DANIÉLOU AND THE PRIMORDIAL TRADITION by Adrián Navigante

- » NO VIOLENCE WILL FORCE US BACK by Ruchira Gupta

- » TALKING TO MICHELANGELO – From letter to conversation to gift by Aveek Sen

- » FIND US… IN GERMAN: DAS INTERNATIONALE INSTITUT FÜR TRADITIONELLE MUSIK BERLIN 1963-1996 by Lars Koch

- » FIND US… IN SPANISH: LA CATÁSTROFE DE UTTARAKHAND by Álvaro Enterría

- » THE PHOTOS AT THE LABYRINTH by Alex Mene

- » A LETTER FROM… DELHI by Dagmar Bersntorff

- » A LETTER FROM… MADRID by Pradeep Bhargava

- » SAMUEL BERTHET, MEMBER OF The ALAIN DANIÉLOU FOUNDATION’S HONORARY BOARD, HONORED IN DHAKA

- » The ALAIN DANIÉLOU FOUNDATION’S UPCOMING EVENTS 2013

- » The ALAIN DANIÉLOU FOUNDATION’S PROPOSALS 2013

The ALAIN DANIÉLOU FOUNDATION’S SUMMER MELA 2013 by David Gimbel

David Gimbel is the founder and Director of Archaeos and a member of the Alain Daniélou Foundation’s Honorary Board

Sophie Bassouls-Daniélou, President of the Alain Daniélou Foundation’s Honorary Board

The Alain Daniélou Foundation continues the oldest long-distance intercultural dialogue that we know to have existed. Long before there was either an ‘India’ or a ‘Europe’, the distant ancestors of those two civilizations were already communicating. Symbolically laden artifacts and writings,bearing the Sumerian and Indus Valley scripts, discovered at Ur in Mesopotamia, demonstrate that a set of complex economic and social relationships that were already occurring between the two regions by the end of the 3rd millennium BCE. Even with the earliest cities, the dimension of ‘culture’ moved, along with material goods, between East and West. The 2013 ALAIN DANIÉLOU FOUNDATION MELA is one of may continuing steps in that ancient dialogic relationship—an intellectual interchange between two geographically distant civilizations that have always held a fascination with each other.

The Alain Daniélou Foundation serves a vital purpose. The further that we move into an imponderable future—one in which we are all bound tightly together into the human family by the ability to travel, to speak and to communicate across vast geographical spaces, but where we may also struggle to survive in a world of diminished resources and a changing biosphere—the more that the facility and ease with which we form interpersonal and intercultural connections is vital. Ultimately, there are more common aspects, loves, and human concerns that bind us together as one people living on a single green and blue planet, than there are differences that might separate us and continue to yield crimson conflict and subsequent ashen greyness. The Alain Daniélou Foundation promises a dialogue between civilizations—hopefully one of many—and it is this type of promise that creates abundance and peace, crafting in its wake that type of future world that we all deserve and shall one day inhabit.

The Alain Daniélou Foundation ’s Director, Ion de la Riva at the inauguration ceremony

Anne Prunet, President of the Alain Daniélou Foundation’s Advisory Committee

Suresh K. Goel, Director General of ICCR, India

Malvika Singh, Director of Seminar and member of

The Alain Daniélou Foundation’s Honorary Board

IMPRESSIONS OF A SPEAKER AT “THE BODY CONFERENCE” by Joseph S. Alter

Joseph S. Alter at The Body Conference,

Zagarolo June 23-24 2013

Joseph S. Alter is a researcher, writer and professor

at Pittsburgh University

The Alain Daniélou Foundation’s Summer Mela was a marvelous event, combining cultural performances, sumptuous receptions, and wide ranging intellectual stimulation – truly a feast for the body and the mind! I have never participated in an event as wide ranging, entertaining and dynamic. It was superbly organized and perfectly executed. The cross-cultural integration of art and culture framed the intellectual conference on the The Body in a manner that perfectly reflected Alain Daniélou’s profound influence.

Ashis Nandy, Isabella Thomas, Joseph S. Alter and Aveek Sen

at The Body Conference

Ashis Nandy speaking at The Body Conference

Shekhar Kapur, member of The Alain Daniélou Foundation’s Honorary Board,

attended the conference

Subodh Gupta, member of The Alain Daniélou Foundation’s Honorary Board,

participating at The Body Conference

ALAIN DANIÉLOU FOUNDATION’S SUMMER MELA IN THE ITALIAN PRESS

The ALAIN DANIÉLOU FOUNDATION’S DIRECTOR, ION DE LA RIVA, VISITS EUROPEAN & INDIAN INTERLOCUTORS

After the Mela, our Director set out to Berlin to prepare the 50th Anniversary IISMC with Lars Koch and Riccarda Kopal in the Etnologisches Museum of Dahlem. He also met our delegate Dagmar Heuer and Silvia Ferhmann, Head of the Communications Department of the House of Cultures of the World, a marvellous multicultural centre for the arts where he discussed with Silvia Fehrmann about music and cinema from India for next year. Dr. Shiva Prakash offered a dinner in Potsdamer Platz and a very inspiring conversation ensued on a project about Shivaism for the future and The translation into Hindi of Shiva and Dionysus.

Berlin will host on November 14th a concert and seminar to mark the 50th Anniversary IISMC and we encourage our friends to be there and enjoy the music and the unique “Berliner luft” which makes the German capital one of the most exciting places in the world today after decades of division and drama. Berlin bleibt doch Berlin… as the song goes, and it discovers its Indian passion. An edition of The Way to the Labyrinth into German is due for nest year too, so we are “echte berliners” at the Alain Daniélou Foundation … One of the most enjoyable recitals was at a private home in Grunewald to welcome the sunrise with dhrupad from Peter Pannke, a true Indian Berliner with a voice and stories to tell. A real treat!

Then London, where the Director met up with Lady Mohini Kent Noon and discussed a project on yoga. A day in Cardiff, Wales to visit the exceptional Indian miniatures exhibition and experience Cymru -India affinities, an interview on the radio with Rakesh Mathur near Trafalgar, with lots of good advice from him, a Visit to the Nehru Centre where one feels at home like a desi FiNDer and very inspiring conversations on India and the UK with brilliant Shefali Malhoutra (it runs in the family) who came up with very good ideas for traditional tribal artists to know more about our Foundation.

Paris after London felt like “le sud”: most people where “en vacances” but our director met very important (and good knowers of Daniélou) interlocutors at the IRCAM, Hugues Vinet, at the IMEC, Yves Chevrefils, and at the Cité de la Musique, Philippe Brughière. We prepared the Nobel Prize to Tagore project with Indian Ambassador to UNESCO, Vinay Oberoi and Apoorva Srivastava, Cultural Counsellor of the Indian Embassy, as well as with the remarkable writer P. Mukherjee during high-tea at his residence. Save the date for Paris: 28th November at the Indian embassy near the Eiffel Tower (yes, we aim high).

Finally, a Swiss grand tour to visit our friends and have our Board of Trustees in Geneva. Great meeting at The Rietberg Museum in Zurich with Albert Lutz, Director and Johannes Beltz, Curator; inspiring talks with Andrew HOLLAND-Director of PRO HELVETIA and Chandra Grover from Pro Helvetia India; enthralling conversation with Alexis Georgacopoulos, Director of ECAL, very interesting meeting with Stéphane Decoutere from the EPFL, an enjoyable encounter with Laurent Aubert from ADEM; highly motivating discussion with Sam Strourdze, Director of the Elysée Museum; and good talks with Charles Kleiber at Le Chateau d’Ouchy Daniélou’s favourite restaurant, where we discussed our official presentation at La Manufacture on April 2014 with indian music and dance. Mind the date too!

And soon to India! The Director will be in India to attend the RIFF and THINK Goa 2013. At the RIFF, Alain Daniélou Foundation will present Manu Chao in concert, first time in India. The Director will host a working lunch for our counsellors in Delhi and will also travel to Varanasi and Lucknow on invitation of Museum Rietberg-Zurich and Muzzafar Ali respectively.

It’s been a hectic summer, but a very rewarding one and we thank all our interlocutors for their enthusiasm and support. Let’s hope Sole finds the same kindness when we go fundraising this autumn…. but we surely will not give up easily, friends are tough cookies!

THE BODY IN INDIAN ART by Naman Ahuja

Dr. Naman P. Ahuja, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi

Naman Ahuja at The Body Conference, Zagarolo June 23-24

‘The Body in Indian Art’, ‘Corps de l’Inde’, ‘India Belichaamd’ will be one of the largest exhibitions of classical Indian art staged in the past 25 years. It is to be inaugurated by the Heads of States of India and Belgium to mark the inauguration of Europalia.India 2013 at the Bozar Galleries in Brussels on October 4th this year. Sourced from 56 museums and private collections in India and Europe, the exhibition is presented in eight thematics. These explore how Indian civilization has contemplated (i) death, the end of the body; (ii) birth and of course re-birth; (iii) the place of astrology and cosmology in determining the fortunes of the body; (iv) the nature of divine bodies; (v) heroism and ideal bodies; (vi) asceticism and the development of practices of healing and yoga; and (vii) it explores the body in rapture, possessed, by art, by nature.

It is not without reason that India is known for its extraordinary love for images. Magnificent sculptures proliferate, covering every available surface of towering temples; paintings, photographs, and prints are used to inform people of their mythology, as subjects of worship in themselves, and as talismans to ward off any malefic force. It is important to note, however, that there is an equally important and enduring history of Indian philosophy which abstains from representing and worshipping bodies altogether. This is the subject of another gallery, (viii) which explores the resistance to the representation of the body.

Naman Ahuja & Kristine de Mulder

from Europalia at The Body Conference

The artworks are put together to provoke larger questions: Where do society’s archetypes of heroism and valour rest, for example? What motivates abstinence and asceticism? How does a civilisation view the rites of passage, death, and birth? To what extent do Indians believe that the body’s fate is destined or predetermined, and to what degree is fortune in the hand of those people who shape it for themselves? Through art, the exhibition shows the body as a site for defining individual identity, negotiating power and a richly layered exposition that also re-examines the weight of classical history in light of our changing views of social exclusion, gender and sexuality. Each of the eight galleries in the exhibition juxtaposes classical Indian art and ideas, with concerns manifest in contemporary art providing both a contemporary counterpoint to the past, as well as civilizational continuities.

Ranging from monumental stone sculptures located in the storerooms of provincial small-towns, to Chola bronzes from Tanjore, and manuscripts about magic painted for the Mughal Emperor Akbar from the fabled library of the Nawabs of Rampur; the exhibition provides the spectator with examples of artworks of unparalleled excellence, many of which have never before been publicly exhibited, nor published.

The exhibition is complemented by a rich array of video documentation of rituals and dance traditions of diverse traditions as well a specially recorded soundtrack of classical music.

The exhibition will close on 5 January 2014

MANY-SIDEDNESS: THE NON-VIOLENCE OF THE MIND by Aidan Rankin

Aidan Rankin is a writer

‘Many-Sidedness’: The Non-Violence of the Mind

Say the word ‘Jainism’ to a well-informed westerner and you are likely to conjure up images of ascetics who cover their mouths and sweep the ground before them with small brushes. They do this to avoid doing injury towards the most minuscule forms of life. Some are also aware of the Jain-owned animal sanctuaries where even the sickest, most deformed birds and beasts are protected and cherished. These overt manifestations of an ancient faith challenge the comfortable – and near-universal – assumption of human precedence over other creatures. For the benefit of lay Jains, and the wider human community, they dramatize the doctrine of Ahimsa: non-violence or, more literally, the avoidance of anything that causes harm.

More than that, the actions of the ascetics, which appear extreme to secular observers, illustrate the idea that all life is interdependent, each life form, however ‘small’ in human terms, is unique but plays a critical role in the natural order. The insights of modern science confirm this insight of the Jain seers. Oceanographers remind us of this principle when they reveal the value of plankton in controlling the temperature and structure of the sea. From the science of ecology, we know that the Earth is a living system made up of many parts, all of which ‘need’ each other. Ahimsa is therefore at once a primal intuition, a personal ideal and a rational programme for life on Earth. The Jains have a motto, Parasparagraho Jivanam, which means ‘all life is bound together’.

Ahimsa is one of the one of the most ancient ideas in Indian culture and is the basis of all the significant Indic philosophical schools. It is arguably India’s greatest contribution to human civilisation, because although not unique to India (the Australian Aborigines have similar concepts, for example) it is most powerfully concentrated in Indic thought. Alain Daniélou was profoundly influenced by the idea, although he rejected the somewhat simplified ‘Ghandian’ definition that was exported to the west during the twentieth century. Rather than exalting meekness and humility, he saw Ahimsa as a sign of intellectual strength and inner composure. The Ram Rajya Parishad (RRP), a party founded in 1948 by Swami Karpatri, promoted Ahimsa as the first principle of its projected ‘dharmic’ political order. Daniélou, who was initiated into Shaivism by Karpatri, served as a political adviser to the RRP and helped to shape its programme and ideology.

Although a frequent critic of Jainism, it is possible that Daniélou might have recognised the Jain equation of non-injury with inner strength. The Jinas, revered by Jains, are spiritual victors, Jina meaning ‘conqueror’, the Jain path signifying the path of conquest. The conquest in question is not external, as in military conquest, but internal. To borrow a phrase from William S. Burrroughs, an author with very different priorities, the Jain is asked to become a ‘cosmonaut of inner space’.

The process of inner conquest is where Ahimsa extends to the intellectual arena. In Jain dharma, the non-violence of the mind is known as Anekantavada. This multi-faceted word is sometimes rendered as Anekantvada or Anekantwad and usually abbreviated to Anekant! It means ‘Many-Sidedness’, or more literally the absence of Ekant, or one-sided, doctrinaire thinking. Anekant provides an inoculation against fundamentalist rigidity and also tempers the strong puritanical current in Jain doctrine that was criticised by Daniélou.

Unlike post-modernist doctrines it superficially resembles, Anekant does not deny the existence of objective truth or suggest that every subjective ‘truth’ is equally valid. Its position is subtler than that, viewing objective truth as such a powerful force that it needs to be approached with humility and care. All humans – and non-human species – are on the same journey towards truth and it is likely to take us many lifetimes to grasp it. The more dogmatically certain someone is the further he or she is likely to be from enlightenment. The more rigid the dogma, the greater the obstacle to spiritual progress becomes.

Accordingly, truth can be approached from different angles, as the summit of a mountain may be reached by different paths, some straight, some winding. But knowledge grows with an understanding that many paths exist and that one’s own is not necessarily the most correct. Our beliefs are mere facets of reality, not reality itself. Jain devotees also liken objective truth (equated with absolute knowledge or full consciousness) to a diamond with multiple facets. Each of these is distinct, but through them the same clear light may be appreciated.

For the modern (or, for that matter post-modern) western consciousness, this approach is radical in the literal sense. It challenges at the root both our thinking and the way we organise our thoughts. In Many-Sidedness, there is no ‘battle of ideas’, because this is considered to be a form of intellectual Himsa or damage, leading quite logically to physical violence and war. The adversarial method gives rise to sterile “debate”, entrenched positions and artificial polarities.

Anekant is a form of mental meditation, whereby attachments to fixed ideas are surrendered. Such attachments are regarded as being at as dangerous and ultimately limiting as material attachments. The goal is a state of equanimity and a sense of proportion, which corresponds to the material aim of living more lightly on Earth. To use a fashionable phrase, Anekant is a process of ‘de-cluttering’, but applied to the contents of the mind and spirit.

Within the Jain tradition, the division between spirituality and science that still dogs so much of western thought simply does not exist. They are seen as part of a continuum, reliant on each other rather than opposed. So “scientific” is Jain thought that Albert Einstein is widely believed to have expressed a wish to be reborn in India as a Jain. George Bernard Shaw, despite his Fabian rationalism, declared explicitly that ‘I adore so greatly the principles of the Jain religion that I would like to be reborn in a Jain community’.

Anekant has enabled Jain communities to survive as minority traditions in India and the Diaspora, adapting without surrendering a distinctive identity. Although Jainism is a non-theistic creed, for instance, Jains in India will frequently worship or focus their meditation upon Hindu deities, especially those closely associated with their localities. From the standpoint of Anekant, there is no contradiction between these two positions. The deities are honoured because they express facets of the truth, as well as representing continuity, rootedness and connection to a wider human community.

In today’s world, the limitations of the adversarial, either/or form of argument are increasingly apparent. Even the mounting ecological crisis is linked to adversarialism, because it arises from a false division between humanity and ‘the rest’ of nature. ‘Either you’re with us or against us’ has been the maxim of the Neoconservative faction in the Anglosphere. It has contributed to a state of perpetual war in which cultural misunderstandings become entrenched. The words themselves were uttered by former US President George W. Bush and perfectly express the adversarial mentality. That mentality, however, is by no means confined to the political or religious ‘right wing’. All too often, as Alain Daniélou well understood, self-styled ‘progressive’ movements apply the same rhetoric of anger and inflexibility and are among the strongest of all purveyors of Ekant.

The principle of Many-Sidedness is by no means confined to Jain dharma. Yet Anekantavada has been built by the Jains over millennia into a complex intellectual system resonating well beyond their other religious and cultural practices. It is part of a larger Indic tradition of tolerance, which Daniélou acknowledged in the polytheism of the Rig Veda. Each deity reflects one of the many aspects of nature or principles of the cosmos. It is also an expression of the divine principle beyond such limited human concepts as ‘one’ and ‘many’. Daniélou compares the polytheistic consciousness to the aesthetic appreciation of a sculpture:

We can look at a sculpture from different angles. We grasp its whole form only when we have observed the front, the back, the profiles. Each of these views is different from the others; some of the elements of their description may seem incompatible. Yet from these contradictory reports of our eyes we can build up a general conception of the sculpture which we could hardly do if we had seen it from one angle only. (1)

What is this other than the principle of Many-Sidedness, expressed with clarity and wisdom?

Note

(1) Daniélou Alain (1991) [1964] The Myths and Gods of India [Hindu Polytheism] Inner Traditions International, Rochester, Vermont. 5

WHICH HINDUISM?

ALAIN DANIÉLOU AND THE PRIMORDIAL TRADITION by Adrián Navigante

Adrian Navigante is a philosopher and writer

One of the most interesting aspects of Daniélou’s work consists in his approach to a very complex and to the modern mind rather polemical subject: the “primordial tradition”. Whoever happens to come across this expression would immediately think of authors like René Guénon, Frithjof Schuon, Julius Evola, Ananda Coomaraswamy and Martin Lings. There is no doubt that Daniélou shares with these authors some basic ideas on the subject. First of all, he conceives knowledge – in the deepest sense of the Greek word gnosis and the Sanskrit term vidyâ – to be inextricably bound to a very particular kind of experience that leads the individual to an ultimate realization of his being. Secondly, he affirms that the transmission of this knowledge is only secondarily bound to a contingency principle affecting form and content of that which is transmitted and related to the finitude of the human condition (like any modern hermeneutics would avow), and primarily linked to a transcendental principle of impersonal nature which is to be traced back beyond existential parameters subjected to time, place, causality and relation. Lastly, he speaks of “initiation” as the proper modality of transmission of this knowledge, and also on the fact that the content to be transmitted does not lend itself to any “profane” manipulation, neither as scientific object of study nor as article of faith – both of which are the result of a general de-sacralisation of experience. Within the frame of his kinship with Perennialism, there’s no denying that the works of René Guénon (of all traditionalists) influenced Daniélou’s early approach to Hinduism. In spite of the fact that Guénon spent the last twenty one years of his life in Cairo and towards the end of his life obtained the Egyptian citizenship, it is known that Hinduism remained for him a more important reference than Islam with regard to the idea of primordial tradition. In his remarkable book Against the Modern World (2004), which is a reconstruction of traditionalism within the intellectual history of the twentieth century, Mark Sedgwick points to the fact that Guénon’s private library in Cairo contained four times more books on Hinduism than on Islam. As Daniélou clearly explains in an interview conceived as introduction to the book Le Mystère du Culte du Linga (1993), the idea of “tradition” he entertained before meeting Swami Karpâtrî was actually that of Guénon, and Daniélou’s interest in some aspects of Guénonian traditionalism led to a very interesting exchange of letters between these two French authors towards the end of the 1940s, which was published in Italian with the title La Corrispondenza fra Alain Daniélou et René Guénon (2002).

However, the interesting aspect of Daniélou’s approach to the subject of primordial tradition does not lie in the similitudes to Guénon and eventually to some other perennialists, but rather in the differences. In fact, Daniélou’s defense of an orthodox type of Hinduism was the fruit of a very original and even controversial approach to Indian philosophy and religion, his rigorous treatment of some aspects of Shaivism was surprisingly intertwined with an artistic (perceptual and symbolic rather than conceptual and systematic) modus operandi, and his conception of inner realization was far away from the metaphysical (or perhaps more exactly: Brahmanic) asceticism propounded by René Guénon. According to Daniélou, bearing witness to the primordial tradition does not have to do with a passive reception of a transcendental magnitude transmitted from generation to generation by means of “initiatic chains” and fragmentarily codified in different “sacred books”, but rather with an active participation of each human being in the immanent manifoldness of a cosmic play encompassing different planes of existence. This active participation introduces an element of innovation and individual creativity within the path of inner realization and depotentiates the role of institutionalized authority (sacred texts, churches, sects and secret societies) in a considerable way. One could say that Daniélou’s approach to Hinduism is aesthetic and religious at the same time, if by “aesthetic” we understand a theory of transcendental perception – instead of the submission to any law alien to the field of experience – and by “religion” an inner transformation of human nature – as opposed to any form of submission to a rigid dogma. In this sense, the primordial tradition reveals an uninterrupted stream in which the macrocosmic and the microcosmic aspects of reality are essentially and reciprocally bound together in a kind of cosmic play, and it is the task of human beings to become aware of this dynamics from the inner side of it, that is, to be able to fully and openly respond – within the frame of one’s own individuality and yet challenging its own limitations – to the magnificence of an all-encompassing, impersonal and never fully understood source of all existence.

A very difficult question that arises as soon as the reader is confronted with Daniélou’s work is that of the relationship between the primordial tradition and Hinduism. René Guénon identified the term Hinduism with a very particular stream that has imposed itself over the last two centuries in the imaginary of Western spiritual authors and seekers: Advaita (non-dualistic) Vedânta. In fact, when he speaks of “Hinduism”, he means brahma-vidyâ, that is, the doctrine of the knowledge of brahman propitiated by the Hindu philosopher and sage Shankara. This doctrine propounds a unity of being (sat) and consciousness (cit) that transcends all forms of relational cognition in order to make the individual aware of the identity of his own living soul (jivatman) with the universal and transcendental Self (brahman). The main question is in which sense this theory of Shankara, which was conceived in the eighth century A. D. and presupposes a long period of Indian intellectual history, can be related to a primordial tradition even prior to the first codified attempts to ascribe an abiding meaning to human experience. According to Guénon, the philosophy of Vedânta, systematized in the writings of Shankara, is not only a compilation but also a distillation of the secret doctrine of the Vedas, the origins of which are not human and surpass the horizon of writing culture, organised religion and even historically individuated parameters of experience. If we follow Guénon’s train of thought, we can see that his approach to Hinduism differs from that of mainstream Western scholarship in two aspects: 1. His affirmation of the transcendental validity of the Hindu doctrines as expression of a universal Gnosis, something that was also a focus point of Fritjhof Schuon’s research, for example in books like De l’unité transcendante des religions (1979) or L’esotérisme comme principe et comme voie (1997). 2. His reduction of all Hindu doctrines to the system of non-dualistic Vedânta, something which results in a regrettable exclusion of Vishnuism and Shaivism from his field of research and enthrones Brahmanism as the only path to the realization of primordial knowledge. Daniélou’s position is in this sense more radical but at the same time more integrative and differentiated. In the affirmation that sanâtana dharma, the unchanging and universal law that accounts for Hindu religiosity (irrespective of the cultural, social and regional variants of it), finds its oldest codification in the written collections of hymns, mantras and magical formulae called “Vedas”, Guénon does not differ from the views of Western indologists in the matter concerning the cornerstone of religious authority on the Indian continent. The so-called “shruti (heard or revealed) literature” of Brahmanic origin stands at the beginnings of Hinduism and for the Indian religious mind constitutes its a-temporal core, while all other religious movements of the Indian subcontinent, from Vishnuism and Shaivism to Jainism and Buddhism, are chronologically to be ordered as historical derivatives of the Vedic tradition. The peculiarity of Daniélou’s approach to Hinduism consists in questioning scholarly truth criteria based on historical documents as the only source of reliability. This does not mean that his conception of a primordial tradition identified with sanâtana dharma is a purely subjective invention. In fact, Daniélou considers his own approach as an unprecedented interrogation of some aspects of mainstream scientific research within the field of Indology that are always taken for granted and practically accepted as unquestionable. In some of his writings like Histoire de l’Inde (1971) and Shivaisme et tradition primordiale (2003), though most explicitly in La fantaisie des dieux et l’aventure humaine (1985), Daniélou attempts a periodization of sanâtana dharma in which the Vedic tradition has neither the oldest place nor the leading role. Taking the status of Sanskrit as a artificial language, that is, a language created for specific purposes of assimilation, transmission and preservation of religious and cultural contents, he affirms that in the beginning was not Vedism but Shaivism, and that Shaivism is in its origins a Dravidian, that is a pre-Aryan religion. This Shaivite canon, which for Daniélou originally consisted of âgamas and purânas written in Dravidian language, did not survive intact in its original version, but since almost the whole pre-Aryan culture was assimilated in the Sanskrit mainstream, fragments of it can be still found in post-Vedic texts, and another part of it appears to a great extent in the Tamil literature of South India. Even if Daniélou distinguishes the Southern tradition of Shaiva Siddhânta, which constitute a remarkable anti-Brahmanic stream of Hindu religiosity, from the Dravidian bearers of the ancient pre-Vedic Shaivism, the native element observable in Tamil religiosity contains in itself a series of elements Daniélou resorts to in order to explain that the Proto-Shaivism of the Dravidians is far away from any doctrine based on moral constraints, asceticism and denial of life. The worship of the phallus, the sacralisation of sexuality and the a-moral or transgressive character of ritual practices are recurring subjects in Daniélou’s treatment of Hinduism. In this sense, the primordial tradition of Proto-Shaivism can only be exhumed by means of a very subtle and highly complex hermeneutical reconstruction. This reconstruction is not based on the same parameters of intelligibility that scholars and historians use in their investigations. For example the Puranic literature, which is for indologists a mixture of mythological invention and historical events, appears in the eyes of Daniélou as a testimonial continuum encompassing not only human, but also divine and cosmic history. This amplified notion of history presents a logic of its own to which Daniélou adheres, especially when it comes to the formulation of a cyclical time encompassing different layers of duration. Actually this manifold duration does not reduce itself to the distinction between kalpa (as cycle of world creation and destruction), manvatara (as a period associated with a group of gods) and yuga (as a measure of human time and social interaction); it presents a very complex schema of different (and simultaneous) levels of existence, perception and consciousness. Although any indologist would characterize the Puranas as belonging to the Vedic tradition – in as far as smriti (“remembered”, i. e. not directly revealed transmission) can be understood as Veda in the broadest sense of the term –, Daniélou insists on the pre-Vedic nature of these writings and maintains that they can be related to the word veda only if the latter is understood as that which is permanent (akshara) and underlies every aspect of created being, as opposed to religious texts in which Brahmanic teachings are fixated and legitimated. With regard to the Agamas he has a similar view: such doctrinal treatises related to the Tantric tradition are reputed to have arisen in the fourth century A. D. or even later, but Daniélou locates the Shaiva-Agamas in the pre-history of the Indian continent, that is at a time previous to the Aryan invasions. To sum up: if Guénon tried to extract perennial contents from the Vedantic treatises of Shankara and affirmed that very stream of Indian soteriology as the esoteric part of Hinduism containing the message of a universal Gnosis, Daniélou claims that Vedic religion stands for the primordial tradition only for those who haven’t established any contact with pre-Aryan Shaivism, where true Hindu esotericism is really to be found. This reaction against Guénon’s reductive method, which appears in Daniélou’s essay René Guénon et la tradition hindoue (1984), is no elitist gesture of someone who spent some time in close contact to spiritual masters of the Shaivite tradition and is bent on showing the exclusive authority of his own path. On the contrary, it is a request for another type of approach to primordial tradition and its relationship to Hinduism – an approach that may lead to a broader understanding of both. The transmission of the primordial tradition is mainly of oral nature and takes place in a milieu where the values of a philosophy of life based on a cosmocentric and integrative view of the universe are actively practised and preserved in spite of the general human tendency to ignore and sabotage this order. Daniélou relates this tendency to the fact that, according to the Puranas, we find ourselves in the last fraction of the Kali Yuga. Surprising as it may sound for those who are not familiar with cyclical time in Hinduism, the Vedic religion is also part of the Kali Yuga, because the mere necessity of fixing a truth which in itself is dynamic by means of scriptural codification is a sign of the estrangement of human beings from the deepest source of their being, and by means of mechanical reproduction of abstract truths the human spirit cannot attain the level of inner realization which was once accessible to the Shaivite religion – even before the beginnings of the documentary legitimated “history of India”.

We should emphasize the fact that Daniélou’s thesis on the Dravidian origin of Shaivism is neither a sheer invention of his own nor can it be reduced to a Perennialist deformation of Hinduism. Eminent authors like Sir John Marshall, responsible for the excavation which led to the discovery of Mohenjodaro and Harappa in the 1920s, George Uglow Pope, the Christian missionary who spent many years in Tamil Nadu und wrote in 1859 the first Tamil Handbook, and the thinker and poet Maraimalai Adigal, founder of the society Shaiva Siddhanta Mahasamajan in Madras and translator of Kalidasa into Tamil, were of the opinion that Shaivism has pre-Aryan origins, and this line of research extends itself until nowadays. At the same time, it is archeologically proved that the Dravidians, as Daniélou indicates in his books, had their own tradition of writing, that they were of African origin and had kinship with Elamite and Sumerian people, and that they introduced their writing system in the Indus Valley before the Aryan invasions and the invention of Sanskrit. What’s more, some Indian scholars, like Chintaharan Chakravarti or Narendra Nath Bhattacharyaa, hold the thesis of an extra-Indian substratum of Tantra still identifiable in some relevant ritual or religious practices like Vâmâcâra, Kulâcâra and the worship of the goddess Târâ. In connection to this last point the Tibetan religion plays a very important role; for this reason it is not at all surprising to read Daniélou’s remarks on the importance of Mahâyâna, especially his observation that the Tibetan variant is the only branch of Buddhism that has preserved Shaivite elements along its own history. Last but not least, Daniélou’s thesis that Vedic religion rejected in the first place the phallus cult of the Shaivites, and that this ancient religiosity of freedom and integral realization was condemned by Brahmanic morality, is something that can be attested through a reading of Vedic texts, for example in the Rigveda the Aryan Rishis express a striking antipathy towards Shishna-Deva (“worshippers of the phallus” i. e. the native people of the Indus Valley).

In his book La fantaisie des dieux et l’aventure humaine, Daniélou makes his point quite clearly: “If we want to understand Indian thought, we have to go to its sources, that is to the great civilization prior to the arrival of the Aryans”. The religion of this civilization was Shaivism in its primordial form, something that according to Daniélou fully expresses the perennial and living tradition called sanâtana dharma. One could say that his approach to Hinduism is so radical that it goes beyond the commonly accepted denomination of Hinduism as a manifold spectrum of religious practices, rituals, ideas and norms of conduct beginning with the Vedas and reaching up to the expansion of the so-called Neo-Hinduism, whose most important exponents are among others Ramakrishna, Ramana Maharshi, Paramahansa Yogananda, Swami Shivananda and Sri Aurobindo. The fidelity to the primordial tradition of Shaivism requires in this sense the acknowledgement of a fracture of time before the Vedic period and the reconstruction of everything that comes afterwards with an eye to re-establishing a past in the past, a pre-history disseminated in the whole course of Indian religion that waits to be discovered and experienced. The human beings who attain this level of experience are able to perceive the nature of the universe without the distortions and veils of an individuated being trapped in the web of its own ego.

NO VIOLENCE WILL FORCE US BACK by Ruchira Gupta

Ruchira Gupta, is the founder of an anti-trafficking organization,

Apne Aap Women Worldwide

Ruchira Gupta participating at The Body Conference

in the Tagore Hall, Zagarolo

As long as I can remember I have always longed for equality, an addiction I owe to my Gandhian socialist father and courageous mother. My home was like a salon, with politicians, writers, journalist, poets, academics and artists, all converging, to talk about how they would create a fairer and more just India.

In my quest for equality I decided to be a journalist and expose all that was unfair in the world. I had the privilege of working with successive progressive male newspaper editors. I was given the dangerous assignment of covering the ULFA armed struggles in the north-east. Blindfolded I hopped onto a scooter with them to meet their leader and scooped a story on how they lived and what they wanted just before Rajeev Gandhi as Prime Minister signed an accord with them.

On another occasion I went into the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya as it was being demolished to see “what was really going on.” And in Mumbai, where the 23 year old photojournalist was raped, I went into a brothel with a camera in the red-light district of Kamatipura.

On the first occasion the ULFA was hospitable and kind, simply sharing a few songs and pamphlets and sending me on my way, but on both the other occasions I was physically attacked. In the brothel a knife was pulled out on me by a customer or a pimp, who said he would not let me film and it was the women in prostitution, who surrounded me and protected me by saying that, “ We want to tell our story. You have to kill us first.” The pimp thinking it was more dangerous to kill 23 women than letting one woman make a film, slinked away and I went to win an Emmy for outstanding investigative journalism for field producing the documentary, The Selling of Innocents. I also went on to found an anti-trafficking organization, Apne Aap Women Worldwide, which has supported more than 15,000 girls and women to access schools and livelihoods.

On the second occasion inside the mosque, my attackers sexually assaulted and then tried to kill me. Someone dragged me to a trench outside and pulled my shirt off. But a passerby jumped in and fought off the attackers. Later, when I testified in court against the attackers, their lawyers asked me questions that inferred I was to blame for the attack. “Did I smoke, what kind of clothes was I wearing, did I believe in God? Why did I go to cover the demolition?”

But none of these deterred me. I considered myself fearless, following the story and reporting on news in the “same” way that my male colleagues would. My desire to prove myself, was perhaps a reaction to all the slights I had heard in the newsroom-that women could not deal with tough assignments, would get tired or scared, were too much of a responsibility and should be sent home early, were always having babies and had to take maternity leave and so should not be given key posts etc.

These slights often translated into a glass ceiling-with mostly men occupying decision making posts. I was ambitious and wanted to be editor, not for the money or the fame, but to take decisions, which would shape the news and in turn my society and country.

When the 23 year old photojournalist was attacked, I heard and read comments that female journalists should not be given dangerous assignments. But it is not due to the nature of our assignments that our clothes are ripped off, or we are sexually assaulted, it is because our very presence in public places angers men, who would love to push us back into the home.

In any case, homes are often the most dangerous places for females from the time they are conceived till the time they die-from foeticide, to incest, child marriage, dowry deaths, domestic violence, maternal mortality and marital rape.

The sexual violence is an outcome of misogyny and can only be stopped by uprooting the deep-seated patriarchy that it is embedded in. This can only be done if more women are in public spaces and more men in private spaces, more men who will take care of child rearing and more women who will be breadwinners. When even in the very newspapers we work in, politics is no longer defined as what happens to men and culture to women. When gender inequalities are reported on with as much vigour as caste, religious and class inequalities.

For example, as a reporter I noticed that famine and farmer suicides was routinely reported, but no investigation is done on the fact that more girls would go to bed hungry on a daily basis, than boys. If I researched murder, I would find that a man’s murder was taken more seriously than dowry deaths and honor killings by the judicial system. In caste conflict, women were the special targets of abuse: rape had become a weapon of war.

No amount of violence is going to force women back into the home. In fact more freedom is the answer, not less.

TALKING TO MICHELANGELO – From letter to conversation to gift by Aveek Sen

Aveek Sen is a journalist and a writer and member of the Alain Daniélou Foundation’s Honorary Board

Aveek Sen speaking at The Body Conference

At an art critics’ conference, recently, I had to talk about whom I write for when I write about art, how I write and, finally, why. This is what I said.

Three years ago, I spent a long summer’s day on my own at Roni Horn’s show, Well and Truly, at the Kunsthaus in Bregenz. Very soon after I entered the Kunsthaus, I knew I wanted to write about the work. This intuitive and thrilling sense of having found a subject is usually the starting point of writing for me. On most occasions when I write on living artists, such as this one, my primary imagined reader is the artist himself or herself. All other readers are necessary and valued eavesdroppers. So, to the question of whom I write for, my answer is simple: for the artist. He or she is the principal addressee of my essay, which I often think of as a letter or an email, but without the sentimental trappings of one, and without the hope of a reply. Yet, the fact of writing to a specific, but imagined, addressee gives a shape and direction to the energy of writing that is invaluable. Sometimes, as it was with the piece on Horn, a reply does come, and becomes the closing of a circuit of communication or, just as often, the beginning of an ongoing conversation, which then produces more writing. This shift of template from letter to conversation is crucial because conversation, the actual exchange of talk, is the medium that I feel most at home in.

I think of conversation as an essential aesthetic and critical medium, and a starting point for a great deal of writing and other forms of making. Like drama and musical performance, it is in the nature of conversations to be ephemeral, perishable events. Their afterlife is in the effect they have on those who make them, listen to them or overhear them. Conversations cannot be captured without being changed fundamentally, but they can be remembered, forgotten, absorbed, resisted or realized. When I write primarily for the artist, I also imagine what I write as a gift that may or may not reach the artist. So, another shift of template: from letter to conversation to gift. Yet, the voice of the writing need not — indeed, should not — be one of direct address; the over-familiarity of such a tone would be presumptuous, intellectually dubious and insufferable for everybody concerned.

It is this impulse to engage with, and implicitly address, the artist directly that is increasingly making me write with art rather than about art. Or write off, rather than of, art. The former is an associative, reflective, idiosyncratic and, sometimes, even fictive form of writing, or a combination of all this, often only tangentially or obliquely related to the subject of the art-work. It inclines me towards artists who are themselves profoundly influenced by, or create their own, reserves of writing — Horn is an important example — and who often think of themselves as creators or authors of books, though not necessarily just “artist’s books”. But this kind of collaborative, rather co-conspiratorial, writing moves in a different direction from, say, the essay on Horn, which was written from a distance, and without getting to know the artist personally, although it may have built the foundations for such an encounter.

To prepare myself for this, more solitary and impersonal, kind of writing, the genres of primary material that I find particularly helpful are the artist’s own writings and interviews. Then, literary fiction and poetry — the poems of W.H. Auden and Wallace Stevens, for instance, Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, Patrick White’s The Vivisector — are, for me, a richer source of ideas, approaches and critical idioms than are overtly theoretical or art-historical texts. This blurring of the distinctions between literature, art, criticism and theory, leading to the use of works of art or literature themselves, or even of music or cinema, as cognitive, analytical and historical tools for understanding other works of art, is crucial to a form of interdisciplinarity that I would describe as unabashedly promiscuous. Such promiscuity demands both rigour and precision, though, which need not be academic or pay excessive heed to the fastidious historicism of a critical practice based strictly on art history and aesthetic philosophy. It is important to address and engage with, yet remain obliquely positioned in relation to journalism, academia and the art-world, so as not to get enmeshed as a writer in the protocols, politics and vested interests of each. So, putting art-writing on the editorial pages of a daily becomes not only a way of making such writing integral to serious public discourse, but also an attempt to challenge and complicate the idea of a ‘serious public discourse’ by an infusion of pleasure and imagination.

Finally, why do I write? To put it plainly, I write on art because I am interested in life, in human beings, in the forms and content of the human experience of time, space and emotions. I want to look at the particulars and specificities of such experience as well as its larger structures — how things repeat or elaborate themselves, how they connect, unravel, loop and spiral, or shoot off in unexpected tangents in our consciousness and in the ordinary, and sometimes extraordinary, lives that we live within ourselves and with people, places and things. I would want my writing on art to be centrifugal rather than self-reflexive, to move outwards from the work and from the writing itself to forms of perception, memory, feeling and consciousness, and towards a heightened and expanded understanding of these forms that is sometimes like a kind of anagnorisis or recognition — a re-cognition, getting to know again what we already knew. So, everything I read, watch and listen to — the books, pictures, films and music — must live in the myriad forms of life that surround me and are absorbed into, and transformed by, my inner life. This inner life is situated in its immediate context, but can never be reduced to a limited understanding of the notion of ‘context’ merely in terms of national, sexual or racial identities — packaged categories that suggest themselves with such alarming readiness in the currently available global discourses on art.

When a venerable American art magazine asked me to write for them, they made it clear that I could only write on ‘Indian’ or ‘Asian’ art. When I wanted to write on Ed Ruscha, Adam Fuss or Graciela Iturbide, they politely tilted their heads and raised their eyebrows. Then, an even more venerable British literary supplement asked me to review books for them, and kept sending me novels by Indian writers writing in English. When I asked for J.M. Coetzee and Geoff Dyer, they politely tilted their heads and raised their eyebrows. While my writing on art is not overtly political, I cannot shake off very easily the blinkeredness of this regionalism, and how it might obstruct writers for whom intellectual and geographical mobility is essential. It makes me sceptical about the much-celebrated idea of the ‘globalization of art’ dissolving stereotypical understandings and perceptions of place. What should we make, for instance, of the fact that the only international magazine that actively encourages me to write on European and American artists happens to be published from Japan?

I want to end by talking about two specific influences on the way I create and structure prose as a vehicle of looking and thinking. First, the idea of writing with one’s ears, and not just with one’s eyes and fingertips, of listening to the voice of one’s writing and shaping its flow musically. In this, the music of Mahler — the symphonies as well as the songs — are a constant inspiration and accompaniment as I write, weaving itself into the deepest structures of my thinking and of the expression of these thoughts.

I use the word, structure, with some deliberation, for structuralist anthropology, most notably the writings of Claude Lévi-Strauss and Clifford Geertz, has profoundly taught me how to think and write. Lévi-Strauss explains, in a series of remarkably lucid lectures called Myth and Meaning, how his notion of the structural analysis of myth as weaving together the simultaneous and the progressive — what is revealed when time is arrested and what unfolds in time — owes itself to a sustained understanding of the structures of Western music, especially to the operas of Richard Wagner.

Such a reading of the interlaced structures of music, experience, consciousness and writing is further embodied, for me, in Proust’s great novel, in which aesthetic philosophy, critical reflections on actual or fictional works of art, and musical elaborations on time and memory are inseparable from the minutiae of love and loss. But its relentless accumulation of these particulars of experience across the six volumes builds up to a larger, colder and more distanced vision of unity — an integrity of structure and of voice. This is a vast system, but it never allows the flow of life and consciousness to harden into rigid structures of representation and analysis. In Search of Lost Time is acutely aware of its own existence in language, but its self- consciousness never becomes a hall of mirrors that traps aesthetic experience in the endless corridors of a Palace of Art.

It is impossible to live in a cork-lined room in Calcutta today as Proust did a century ago in Paris, shutting out the madness, beauty and violence of the real for the sake of the preciousness of mortal time. For me, that impossibility is a consolation — history and geography separate his Paris from my Calcutta. But here I am, in a city far away from home, talking about a 21st-century American artist inspired to produce work by a 19th-century poet, Emily Dickinson, whom she read for the first time in Iceland, of all places — a homeland of the spirit, formed by shape-shifting bodies of lava, water, snow and steam. This web of connections is what writing must try to grasp or set free, in the elusive theatre of an escape-artist’s work, where word and image defy the gravity of place and identity, and make, with delight, their leaps of faith.

FIND US… IN GERMAN

DAS INTERNATIONALE INSTITUT FÜR TRADITIONELLE MUSIK BERLIN 1963-1996

by Lars Koch

Dr. Lars-Christian Koch is the Director of the Phonogram Archiv, Statlische museen zu Berlin

Das Internationale Institut für Traditionelle Musik wurde 1963 in Ber lin mit Unterstützung der Ford Stiftung gegründet und vom Senat für Kulturelle Angelegenheiten Berlin gefördert. Prägende Persönlichkeiten dieser Gründung waren Willy Brandt, der französische Maler und Musiker Alain Danielou – der Gründungsdirektor war -, der indische Sitarspieler und Komponist Ravi Shankar sowie der Geigenvirtuose Yehudi Menuhin.

Das Ziel des Instituts war die Dokumentation von Musikkulturen, die allgemein als traditionell bezeichnet wurden, um diese zu erhalten und Kenntnisse über sie der Öffentlichkeit zugänglich zu machen.

Der Gründungsdirektor des IITM war Alain Danielou, ein bretonischer Intellektueller und Kenner asiatischer Kunst und Musik. Nach einem langjährigen Indienaufenthalt kehrte er nach Europa zurück und arbeitete als Berater für die Musikabteilung der UNESCO in Paris. Danielou. Er übernahm die Direktion des IITM und leitete dies zehn Jahre lang. Sein engster Mitarbeiter war Jaques Cloarec, der auch nach dem Ausscheiden Danielous aus dem IITM diesem eng verbunden blieb und seine Ideen und Ideale weiterführte und seinen Nachlass verwaltete.

In der Zeit bis 1973 entstanden zahlreiche Tonaufnahmen und Fotos, deren Inhalt geprägt ist durch Forschungen über indische, kambodschanische und indonesische Musikkulturen. Ab 1973 übernahm zunächst Ivan Vandor die Aufgabe des Dirktors am IITM, er hatte einen Forschungsschwerpunkt auf die Musik Tibets gelegt. Nach seinem Ausscheiden aus dem Amt wurde eine vorübergehende Vertretung durch einen Senatsangehörigen eingerichtet, bis1986 der Schweizer Musikethnologe Max-Peter Baumann die Leitung übernahm. Baumann arbeitete eng mit den Musikethnologen Hassau Habib Touma und Ulrich Wegner zusammen, man engagierte sich verstärkt für den Bereich der Publikationen, wie etwa der Zeitschrift „World of Music” und zahlreicher Musikveröffentlichungen.

Mit Gründung des Internationalen Institut für Traditionelle Musik entstanden in Berlin die wegweisenden Metamusik- und Horizonte-Festivals wie auch die vom Institut initiierte, europaweit vernetzte Konzertreihe »Festival Traditioneller Musik«.

Bedenken wir die sehr spezielle politische Lage Berlins während des Kalten Krieges von 1963 bis 1990 und die damit verbundene Rolle des IITM, kam es trotz weltweiter Proteste nach der Wende 1996 zur Schließung des Instituts, es hatte seine politische Rolle gespielt.

Diese Schließung hatte Auswirkungen auf das Musikleben Berlins, denn seit Mitte der 1990er Jahre sind „traditionelle“ musikalische Formen im Veranstaltungsbetrieb unterrepräsentiert.

Mit der Rückkehr von Max-Peter Baumann nach Bamberg, siedelte auch das gesamte Archiv des IITM (Bibliothek, Tonband-Sammlung, Geräte) an die Universität Bamberg um. Der Berliner Senat blieb aber weiterhin Eigentümer der Bestände des IIT-M. 2006 sollte infolge der Verlegung der Professur Baumanns nach Würzburg auch der Bestand des ehemaligen IITM nach Würzburg gebracht werden.

Die zuständige Senatsstelle nahm nach Rücksprache mit der Abteilung Musikethnologie, Medientechnik und Berliner Phonogramm Archiv des Ethnologischen Museums Berlin und der Gesellschaft für traditionelle Musik e. V. Verhandlungen auf. und veranlasste in Abstimmung mit Baumann den Umzug der gesamten Bestände des IITM nach Berlin. Seit 2008 ist nun die Musikethnologische Abteilung des Ethnologischen Museums zu Berlin im Besitz dieses Teils des Nachlasses des Internationalen Institut für Traditionelle Musik.

Bis heute ist das IITM als einzigartiger Ort im Gedächtnis aller Musikinteressierten geblieben. Sir Yehudi Menuhin drückte dies 1975 folgendermaßen aus: “Eine der faszinierendsten Ein richtungen in der Welt ist das Internationale Institut… in West-Berlin.- Heute können wir in einer stillen Villa eines Vor orts derselben Stadt durch die ganze Welt der Musik reisen, womit kulturelle menschliche Wünsche erfüllt werden, von denen man in meiner Knaben zeit noch nicht geträumt hätte.”

FIND US… IN SPANISH

LA CATÁSTROFE DE UTTARAKHAND by Álvaro Enterría

Álvaro Enterría is the founder and publisher of Indica Books

A mediados de junio de 2013, una gran catástrofe se abatió sobre una zona de los Himalayas. Es asombroso que esta tragedia apenas llamara la atención de los medios de comunicación españoles.

El 16 de junio, una gran cantidad de lluvia cálida cayó encima de Kedarnath, a más de 4000 metros de altura. Por efecto de la lluvia, una gran cantidad de hielo de un glaciar se derritió, precipitándose sobre el templo de Kedarnath. El templo resultó indemne, pero las construcciones a su alrededor fueron barridas. En todos los ríos de la zona, inmensas riadas arrastraron todo lo que estaba a su paso. En plena temporada de turismo, varios miles de personas murieron y varios miles más quedaron aisladas. Más de dos semanas después aún siguen los trabajos de rescate. Frente a la ineptitud del gobierno para hacer frente a esta emergencia, ha destacado el gran trabajo que ha hecho el ejército, que rescató a más de 90.000 personas. Los daños materiales son inmensos, y se necesitarán varios años para recomponer la zona.

El estado indio de Uttarakhand contiene una gran cantidad de templos y lugares de peregrinación. Durante la última década, el “turismo espiritual” interno se ha multiplicado por diez. La clase media india combina religión y vacaciones en las montañas, fuera del calor agobiante de las llanuras; a éstos se suman los turistas extranjeros. Todo esto hace que el estado reciba (la mayor parte en los meses de verano) 26,8 millones de turistas, frente a una población local de 11 millones. Para hacer frente a esta avalancha, hoteles sin número, caros y baratos, se han construido, a menudo ilegalmente, en lugares peligrosos como los bordes de los ríos. El tráfico motorizado se ha multiplicado por diez en los últimos siete años. En los años anteriores, varias voces se habían alzado para prevenir de la posibilidad de una catástrofe, pero no se hizo nada: el gobierno del estado estaba muy contento con el dinero que fluía y daba trabajo a la población local.

Por otro lado, la deforestación es galopante, se construyen cada vez más carreteras (a menudo al borde de los ríos), se da carta abierta a empresas de minería y se aprueban innumerables proyectos hidroeléctricos, enormes presas o pequeñas turbinas que necesitan sin embargo que el agua se saque de su lecho para ser llevada en túneles subterráneos. En total, el 70% del agua de la región está en manos privadas. Todo ello alegremente y sin estudios serios de impacto ambiental, y especialmente, de su impacto conjunto y convergente en una zona frágil y de alta peligrosidad sísmica. Hay que tener en cuenta que el Himalaya, la más joven de las montañas del planeta, continúa creciendo.

Esta ha sido la mayor catástrofe en India desde el tsunami de 2004, y representa una llamada de atención para India y para el resto del mundo. El calentamiento global es más perceptible en el Himalaya que en otras regiones. Y la actividad humana, motivada sólo por ganancias a corto plazo, no hace más que empeorar las cosas. Según Maharaj K. Pandit, director del Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies of Mountain & Hill Environment en la Delhi University: “El desastre fue provocado por acontecimientos naturales, pero la catástrofe —la trágica pérdida de vidas humanas— fue provocada por el hombre”.

La calamidad que se ha abatido sobre estos lugares de peregrinación y sobre tantos peregrinos ha causado muchas interpretaciones religiosas: la catástrofe sería una respuesta a la comercialización y banalización de los tirthas (lugares sagrados), unos lugares alejados del mundo en plena naturaleza, a los que antes se acudía con gran devoción a lo sumo una vez en la vida. Y, quizás, una respuesta de Alaknandá y Mandakiní, los ríos que forman Gangá (el Ganges), frente a los intentos de encerrarlos en presas. Para construir una inmensa presa en Srinagar, el gobierno quería desplazar el templo de Dhara Devi, una forma de Kali. A esto se opusieron muchos líderes religiosos, pues el emplazamiento de los templos no es casual, y éstos no pueden ser trasladados sin más a otro lugar. El gobierno desmanteló el templo de Dhara Devi justo el día anterior a la catástrofe. Las diosas hindúes, como la Naturaleza, tienen dos facetas: amorosas y maternales, pero también, cuando se las irrita, terribles y destructoras.

Por otro lado, en un paralelismo digno de asombro, por las mismas fechas la ciudad de Lourdes, en el sur de Francia, sufrió también una gran inundación que la sumergió bajo 1,40 metros de agua, causando grandes daños, y la gruta del santuario fue evacuada.

Se explique en términos religioso-mitológicos o ecológicos, la tragedia de Uttarakhand supone un toque de atención —uno más— para que la humanidad comprenda que debe variar su rumbo. Un toque de atención que, mucho me temo, será tan ignorado como los anteriores…

THE PHOTOS AT THE LABYRINTH by Alex Mene

The photographic archives of the Alain Daniélou Foundation at Zagarolo largely consist of the photos taken by Raymond Burnier and Alain Daniélou during their stay in India between 1935 and 1955. Those years were an intense, deep, crucial and vital period in the life of the two artists. They left thousands of images and testimonies of the Hindu archaeological heritage and they portrayed, through these photos, daily life around the temples and throughout the country. Although most of the photos were taken by Raymond Burnier, there are others by Alain Daniélou, who acted as his assistant and made the final touches to the copies. It is consequently very difficult, in many cases, to confirm final authorship, and the images can be considered as the photographic work of both authors.

The photos that Raymond Burnier and Alain Daniélou took during their stay in India show their love for this country and their admiration and respect for its culture, heritage, history and way of life. From a technical point of view, most of them are in a really good state and manifest great technical skill. They constitute an interesting and unique display of the archaeological heritage of India, pioneering such work, and are a source of utmost importance in approaching the architectonic and cultural legacy of India. From an artistic point of view, the images show unconventional sensitivity and an absence of prejudice in the search for beauty. These exceptional photos seem absolutely contemporary. They constitute an exceptional inventory, not only on temples and sculptures, but also on landscapes, people and lifestyle at the time. This really beautiful archive contains the memory of India and its art.

Álex Mene

(Photographic Consultant)

Zagarolo, Italy. Summer 2013

Ruins of a temple. Columns doing the shape of a polygon, Bodh Gaya, by Raymond Burnier

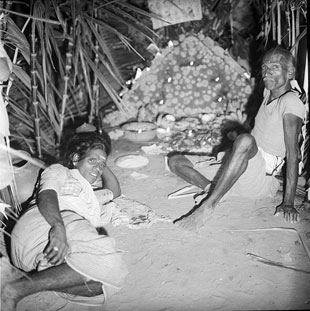

A couple, man and woman, in a hut, South India, by Raymond Burnier

People seated near a temple under the branch of a tree, Khajuraho Temples, by Raymond Burnier

Portrait of a woman standing up in front of a house, Puduchery Carnival, by Raymond Burnier

A LETTER FROM… DELHI by Dagmar Bersntorff

Dagmar Bernstorff is a writer and publisher

RAIN ACCROSS CULTURES

Dear Friends,

Monsun time – rain time: for Indians it is the best season of the year. Not so in Europe: rain is dreaded, its uncomfortable, cold, spoils your holidays. We urbanised Europeans have forgotten how important water is for farming. The people in Europe with the closest relationship to rain are the British. The BBC weather report invariably tells us where in the world it will rain in Africa, America or Asia. Remember the ‚flotilla’, the boat parade on the river Thames in honour of Elizabeth II’s sixty years jubilee as Queen on June 3, 2012? As thousands of boats big and small passed, drizzle changed into rain. Within seconds the crowds on the river bank produced a sea of umbrellas, the spectators suddenly wearing anoracs. The British don’t get defeated by rain!

In India the monsun rains are eagerly awaited to bring respite from the intense heat of the summer. Usually the South-West Monsun hits the coast of Kerala in the first week of June and travels north, reaching Delhi and surrounding states at the end of June or during the first weeks of July. It is an anxious wait, will the rains come on time, will they be late or even fail, will there be too much water or too little? Can the Monsun cover the whole of India or will some areas be hit by drought? Heavy clouds appear as messengers, they break with fury. Children run out of the house to get drenched. The majority of the Indian population still lives in rural areas and depends on agriculture.

Drought or flood threaten their existence.

Still – the weeks of the Monsun are considered to be the best time of the year. Dust has been washed away, the trees and bushes burst into new leaves, meadows are greening, growing food for the cattle. It is a time for contemplation, communication, bonding, love. A time to be at home. Travel is uncomfortable, even risky. The itinerant monks and sadhus stay put in one place at their monasteries, ashrams or in the homes of their disciples. It is a time for listening to special music, monsun ragas like Madhu Malhar or Mian ki Malhar and many others.

A lot of festivals happen during these months according to the lunar calender. Rakshabandhan – when sisters visit their brothers and tie a thread around their wrists, signifying the bond between brothers and sisters. Among Hindus brothers are obliged to see to the wellbeing of their sisters – and, of course, they have to give a present! The Teej Festival, intensely celebrated in Rajasthan with dance and music, remembers the reunion of Shiva with his wife Parvati after hundred years of separation – so the legend goes. It is observed mainly by married women. Janmashtami, the birthday of Krishna, is also due in August. He is a god with very human qualities, hence most popular and easy to identify with. In South India Onam will be observed for ten days in September. It celebrates the rice harvest. Whereas most Indian festivals belong to one or the other religious community here members of all faiths participate. Legend has it that the mythical King Mahabali visits from the underworld to look after his people. His rule is remembered as a golden era : ‚All people were equal…’

These festivals are, of course, opportunities for lavish meals with unique dishes only served during this period, like pine-apple curry or cooked jack fruit. In traditional families where alcohol would not be served, it is allowed to offer ‚bhang’ at these dinners – a drink laced with cannabis leaves and flowers, which grow wild in India.

The 5th century Indian poet Kalidas wrote:

‚May this season of manifold joys

Fulfill your hearts inmost desires’.

A LETTER FROM… MADRID by Pradeep Bhargava

Pradeep Bhargava, Consultant and FRIEND of The Alain Daniélou Foundation

“If you need a shot of energy, go to el Rastro” was one of the first suggestions I received when I first arrived in Madrid. So off I went on my first Sunday in Madrid, because Sunday morning is the only time when you can get this potent energy shot.

Not only did I leave feeling energised, I left with more books and bric-brac than from any other flea market I have been to ever. Not even the Paharganj old book market in Delhi!

The main street – Ribera de Curtidores or “riverside of tanneries”- is where it all is said to have started way back in the 15th century. El Rastro means “the trail” and the market probably owes it’s name to the tanneries (some still stand) that were once located in Ribera de Curtidores. Close by, on the banks of the Manzanares River, was an abattoir and transporting the slaughtered cattle from the abattoir to the tannery left a trail of blood along the street. And this trail – el rastro – is where the current flea market has come to stand.

But, dear friend, I suggest you give the main street a miss. It is full of brand new made-in-China stuff. Go to the by-lanes, get lost. That is where you will get a glimpse of a Madrid rarely seen elsewhere. Go to the Calle Fray Ceferino Gonzalez where you can buy domestic animals. Or the Calle San cayetano, full of paintings and an ocassional painter. If it is old and rare books you are after, don´t miss the Calle Carnero and thereabouts. Plaza de Campillo de Nuevo Mundo is where I go with my son to swap and trade cards or look for old comics. And then there are the gypsies – los gitanos – who trace their origins to Rajasthan selling right from socks to antiquities, or so they claim.

To top it all thee are some very nice age-old bars around the area where you can con only let your taste buds go crazy over tapas and cañas but also rub shoulders with very cool people!

Being from India, you know what is the best part? So much of humanity and of all hues makes you feel really at home!

SAMUEL BERTHET, MEMBER OF THE ALAIN DANIÉLOU FOUNDATION’S HONORARY BOARD,

HONORED IN DHAKA

» “Adieu, Dr. Samuel Berthet”, The Daily Star, Monday, September 2, 2013: read the press article

ALAIN DANIÉLOU FOUNDATION’S UPCOMING EVENTS 2013

- » JODHPUR RIFF. The Alain Daniélou Foundation introduces French-spanish musician Manu Chao in one of best festivals in India.Jodhpur, India. 18th OCTOBER 2013

- » 50th ANNIVERSARY of the INTERCULTURAL INSTITUTE FOR COMPARATIVE MUSIC STUDIES (founded by A. Daniélou, 1963)Berlin, Germany 14th NOVEMBER 2013

- » COMMEMORATION OF THE CENTENIAL OF TAGORE’S NOBEL PRIZE (1913)Paris, France 28th NOVEMBER 2013

The ALAIN DANIÉLOU FOUNDATION’S PROPOSALS 2013

» WHERE TO GO…

- » JODHPUR RIFF – October 18-20, 2013 – Jodhpur, India

- » EXTRAVAGANT INDIA – Festival international du film Indien – October 15-22, 2013 – Paris, France

- » RIVER TO RIVER – Florence Indian Festival – November 22-28, Florence – November 29-December 1, Rome

- » THINK FESTIVAL – November 8-11, 2013 – Goa, India

- » EUROPALIA INDIA – October 4, 2013-January 5, 2014 – Brussels, Belgium

» WHAT TO READ…

- » REVOLUTION FROM ABOVE: INDIA’S FUTURE AND THE CITIZEN ELITEby Dipankar GuptaRupa Publications, 2013

- » EL MISTERIO DE LA DIOSA TRIPURA (Tripurā Rahasya)

Anonymous, translation by Javier Ugaz and Jesús Aguado

Editorial Olañeta, 2009 - » THE BLUE-NECKED GOD

Indira Goswami, Translated by Gayatri Bhattacharya

Zubaan Books, 2013 - » INDIA, A PORTRAITPatrick FrenchKnopf, Borzoi Books, 2011

- » YOUNG TAGORE: THE MAKING OF A GENIUSSudhir KakarPenguin Books, 2013

- » WOMEN CHANGING INDIAUrvashi Butalia and Anita Roy (Ed)Zubaan Books, 2010

» WHAT TO SEE…

- » VISIONS OF MUGHAL INDIA: THE COLLECTION OF HOWARD HODGKIN National Museum Cardiff, Wales, UKFrom 27 Jul–3 Nov 2013, free entry and family activities

- » ‘THE IMAGINARY ORDER OF THINGS’ by SUBODH GUPTA CAC MALAGA, Málaga, SpainUntil 10 October 2013

- » 55th ART EXHIBITION, BIENALE DI VENEZIA 2013 Dayanita Singh at the Deutscher Pavillion Until 24 November 2013

» WHAT TO LISTEN TO…

- » ASIAN DUB FOUNDATION New Album “A History of Now”

- » SUSHEELA RAMAN Extraordinary voice

- » RIZWAN – MUAZZAMQawwali music

» ON LINE RESOURCES…

- » Interview to Director de la Riva by Rakesh Mattur at Sanskriti (ResonanceFM-London)

- » Pradhan Mantri, politics based TV serie narrated by Shekhar Kapur

Published by the Alain Daniélou Foundation .

| Representative Bureau – Paris: 129, rue Saint-Martin F-75004 Paris France Tel:+ 33 (0) 9 40 48 33 60 Fax : + 33 (0) 55 48 33 60 |

Head Office – Lausanne Place du Tunnel, 18CH-1005 Lausanne Switzerland |

Residence – Rome: Colle Labirinto, 2400039 Zagarolo, Rome – Italy Tel: (+39) 06 952 4101 Fax: (+39) 06 952 4310 |

You can also find us here

For contributions, please contact: communication@fondationalaindanielou.org

© 2013 – Alain Daniélou Foundation

hhttps://www.facebook.com/FondationAlainDanielou

hhttps://www.facebook.com/FondationAlainDanielou  https://vimeo.com/fondationalaindanielou

https://vimeo.com/fondationalaindanielou