“Without contraries is no progression”

William Blake

Index:

- » EDITORIAL, by Jacques Cloarec

- » LILARASA, by Adrián Navigante and Sarah Eichner

- » LEWIS THOMPSON AND ALAIN DANIÉLOU: POETRY, MUSIC AND LEVELS OF PERCEPTION, by Adrián Navigante

- » LIFE AND ART, by Madhavi Gore

- » THE MANY ASPECTS OF THE DIVINE, by Sarah Eichner

- » INDIAN TELEVISION: A FAMILY AFFAIR, by Himadri Ketu

- » INFLECTING THE FOREIGNER’S DISCOURSE, by Samuel Buchoul

- » Alain Daniélou Foundation: UPCOMING EVENTS

EDITORIAL, by Jacques Cloarec

Dear Friends and Collaborators of the Alain Daniélou Foundation,

On October 4th we commemorated Alain Daniélou’s birth, which took place 107 years ago. Until his death in 1994, Daniélou never stopped writing and transmitting his perception of Indian civilization in its entire spectrum.

It is at this point – twenty years after his death – that the Foundation has the opportunity of counting among its staff Adrián Navigante, who has the right qualities and competences not only to do justice to the heritage Alain Daniélou handed down to us, but also to initiate an intellectual dialogue with India, something essential for us because of the very name of the Foundation and also because of the new orientations we wish to embark upon.

In this way we can re-establish a balance between two different but complementary poles, the presence of which permeates the whole of Daniélou’s work: the intellectual and the artistic. Adrián Navigante and his assistant, Sarah Eichner, lead the first pole. The second has for seven years been under the guidance of Riccardo Biadene and his assistant, Petra Lanza.

As part of his assigned duties at the Alain Daniélou Foundation, Adrián Navigante has immediately taken charge of the Newsletter and fashioned this number with an eye to revealing to our readers something of the new impulse coming from his area – not only with regard to this specific number of Indialogues but also to the whole sphere of intellectual dialogue. It is for this reason that you will find a clear emphasis given to such contents, and we hope very much that you appreciate them.

As to the sphere of artistic dialogue, its visual and auditory nature are integrated in this case from within the intellectual reflections, as for example in the considerations about poetry and music or in the mandalic symbolism (both Indian and Chinese) as a metaphor for the integral work that constitutes the Alain Daniélou Foundation’s initial goal and desideratum. These contents call all be found in this issue of our newsletter.

We have still many projects to come from Adrián Navigante as well as Riccardo Biadene. Both of them fill us with enthusiasm and all members of the team are projecting their energy in these initiatives.

There is still one very important point to be mentioned concerning the balance of the whole and the importance of a reciprocal form of dialogue. Since the Alain Daniélou Foundation regards it as a priority to work in this direction, we are determined to open a centre in India that may run parallel to our centre in Italy (which is perhaps too “westernized”), all this in spite of regrettable financial limitations due to the over-expenses of 2013, something which reduces our material possibilities not only for this year but also for 2015.

There is no doubt that we are facing a renewal with very well defined contours, which makes me very happy and want to share my best hopes for the future with you all.

Good reading and best wishes,

Jacques Cloarec

Acting General Director

LILARASA, by Adrián Navigante and Sarah Eichner

Alain Daniélou Foundation’s motive force: līlā rāsa

The story about rāsa līlā is perhaps too well known to be repeated here: from the Bhagavata Purāna to Kathak dance, one can find all sorts of elaborations, variations and combinations of one of the main thematic complexes of Indian culture: the combination of loving devotion, aesthetic playfulness and the experiential level of embodiment. But on this occasion the chosen mandala serves as a motif and perhaps also as a sign of hope for the team-work of the Alain Daniélou Foundation from now on.

So we take the liberty of inverting the terms and begin with līlā, a word that introduces a delightful difference between European and Indian tradition by emphasizing the playful (aesthetic, creative and joyous) dimension of creation in the latter – from which Europeans can learn a lot. Not only do we have Krishna (who appears in the image above playing the flute as a symbol of an ever-lasting dancing community), but also Shiva, an oftentimes violent and terrible deity (for example in his Bhairava aspect) associated with destruction. He acts according to cosmic rhythms – those of his own dance (hence his name Nataraja), so that the universe, as we can read in the Shiva-Sutras, becomes in this sense his own work of art. It is the manifestation (ābhāsa) of his power (shakti) that dictates the destiny of the world in which not only a place but also a specific task as human beings is assigned to each one of us.

Alain Daniélou understood this task as active participation in the beauty of creation. If we bear in mind the whole scope of his message, participating in the divine play with the degree of consciousness Daniélou demanded is perhaps one of the most difficult challenges. It requires openness, creativity, inner balance, discipline and above all a mature and humble awareness of our limited range of action as individuals in this never-fully understood experience called “life”. In other words, it requires not only the presence but also an active awareness of others – and even of diversity beyond the human scope.

From this perspective we can say that rāsa in the mandala above symbolizes the harmonic union of a group, the “embodiment” of experiences that surpass the range of an encapsulated individual who is hardly aware of the playfulness of the whole and remains as a result alien to every true form of communication, inner growth and realization of essential tasks. The dancing body of the group seems to us not only an essential element to analyze perception changes taking place in the world around us, but also a symbol of the way in which the participants of the Labyrinth at the Alain Daniélou Foundation should engage in their own task: to keep Daniélou’s multidisciplinary heritage alive at the highest level of vibration (spanda).

Adrian Navigante (director of intellectual dialogue)

Sarah Eichner (assistant to intellectual dialogue)

LEWIS THOMPSON AND ALAIN DANIÉLOU: POETRY, MUSIC AND LEVELS OF PERCEPTION, by Adrián Navigante

Adrián Navigante: Alain Daniélou Foundation research and intellectual dialogue

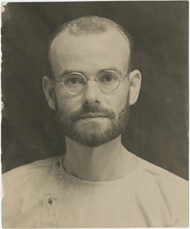

Lewis Thompson

The history of the artistic and intellectual European diaspora at the time of World War II gravitating on the Indian subcontinent (and to a great extent between the two symbolical points of Shantiniketan and Varanasi) remains a challenging task for future research. Unfortunately no comprehensive study has hitherto been published with an eye to reconstructing the context and exposing the principal traits of each one of the actors – varying from the artistically refined to the spiritually eccentric – involved in this singular Indian adventure. The list of names is at first glance quite heterogeneous and includes spiritual seekers of Vaishnavite affiliation like Ronald Henry Nixon (who after serving as a British pilot in World War I became a saṃnyāsin and changed his name to Krishna Prem), artistically and intellectually talented Buddhists like Ernst Lothar Hoffmann (better known as Lama Anagarika Govinda after his conversion to Tibetan Buddhism), female painters and dancers with a radical bent to Hindu arts and religion such as Alice Boner and Stella Kramrisch (the latter being perhaps the only Western woman to have experienced the drastic Aghori test of śāvasādhanā), spiritually multifaceted personalities like Blanca Schlamm (an Austrian Jewish aristocrat who was involved in Theosophy and the Krishamurti school and later on became a devotee of Anandamayi Ma, being renamed Atmananda), the eccentric “Danish sadhu” Alfred Sorensen (who named himself Shunyata and claimed to have been initiated after receiving a telepathic message from Ramana Maharshi) and the poet Lewis Thompson, whose inner voyage from the ego to the Self was dramatically expressed not only in his own writings but also in the different stages of his short life (1).

Alain Daniélou

It wouldn’t be exaggerated to say that a lasting symbolic trace of this intellectual and artistic diaspora was the Rewa Kothi palace at the center of Varanasi, where Alain Daniélou and Raymond Burnier lived from 1937 to 1954. This place was on the one hand impregnated by the Indian spirit of wandering monks who were permanently welcomed (2), while on the other it had an artistic significance because of the combination of activities incarnated in the figures of Daniélou and Burnier: music, literature, photography, painting and the presence of Shaivism permeating the whole specter of their artistic and intellectual enterprises. It might be an exciting task for future researchers to establish the manifold connections among all the abovementioned figures of this pioneering diaspora in India, most of whom shared a sojourn at Rabindanath Tagore’s college Visva Bharati (today a University) and a deep immersion in the main aspects of Hindu or Buddhist religion and way of life. One of these connections, to which we shall refer in this article, is the one between Lewis Thompson and Alain Daniélou.

There is no denying that the lives of these two eminent artists differed from each other to the extent that they even appear as opposites: Thompson was an Englishman of Protestant upbringing – which left negative traces in his soul throughout his whole life – who became fascinated with the combination of Neo-Hinduism and Christianity, chose to follow the way of tapas and vairāgya and went through a Rimbaudian “season in hell” of self-discovery and self-purification up to the end of his short life; Daniélou was a Frenchman who grew up in a conservative Catholic milieu, freed himself early enough from it, embraced the particular ethos of orthodox Hinduism in its manifold aspects (āśrama, varṇa, jñāna, etc.) – rejecting as a result of that the influence of Neo-Hinduism (especially its ascetic message) on the Western spirit –, lived a long and very productive life and succeeded in developing an ars vivendi integrating what he had learned in India with aspects of the Western pre-Christian (Greek and Roman) heritage. Taking this image of opposites as a starting point, one is almost forced to ask what might have brought these two personalities to a certain point of time in the “City of Light” . But what at first sight seems surprising turns out to be evident and even a kind of logical consequence if one goes beyond the surface of convention and takes a look at the deepest layer of artistic commitment (where “commitment” and “existence” become indistinguishable): Lewis Thompson was a poet, Alain Daniélou was a musician, and they shared a singular intuition concerning Hindu metaphysics and its consequences on the level of artistic performance. Such intuition can be articulated in many ways, by different methods and with varying intensities, but we can summarize it in a few words: there is an aesthetics of the Indian spirit with which Western culture is not familiar, and there is a concrete experience to be gained from this type of aesthetics, an education of the spirit whose very conditions usually escape the modern Western mind.

Although Lewis Thompson’s two-volume journals do not abound in references to Daniélou, they do contain entries that enable the reader to reconstruct not only concrete circumstances concerning their lives (for example the fact that, due to his extreme austerities, Lewis Thompson – often undernourished and ill – had to be assisted by Daniélou when he was in need of food, medicine and shelter (3)) but also affinities related to the experience of poetry and music. Perhaps the most interesting point of these affinities revolves around the notion of perception, its different fields and manifold levels, especially with regard to music. Two journal entries from Lewis Thompson (dated 17.II. and 27.II.1944) are of particular relevance in this respect, because they concern shared experiences with Daniélou. In the first they listen to a Barcelona gipsy canto by Manuel Villejo and the first and second movements of César Franck’s violin sonata in A major. The poet’s impressions on Franck’s sonata after a dose of bhāṅg are not precisely benevolent: “every note was in fact flattened, and degraded, half-muted, the vertical column of overtones stifled and distorted, and these mutilated resonances knotting in the air into an ugly, damping, almost sinister tangle” (4), and he adds an interesting comment: “Daniélou says that after his practical and theoretical work on ‘traditional’ music he normally perceives this now” (5). In the second entry Thompson comes back (ten days later) to his experience with Franck’s sonata: he listens to it once again – this time without bhāṅg – and concludes: “I find exactly the same monstrous distortion and impurity” (6).

These impressions seem to confirm intuitively what Daniélou elaborates in his study of musical scales, a book published in London a year before Thompson’s journal entries (7). According to Daniélou, one of the main problems of Western music is the generalized use of equal temperament, which led to an over-simplification of musical structures and a complete disregard of the most elementary acoustic realities. Daniélou’s verdict on this aspect of Western music reminds us of Thompson’s impressions upon listening to Franck’s sonata, since he says that it “rendered the meaning of chords vague and unclear” (8) and adds by way of general comment: “The result is that Westerners have more and more lost all conception of a music able to express clearly the highest ideas and feelings. They now expect from music mostly a confused noise, more or less agreeable, but able to arouse in the audience only the most ordinary sensations and simplified images” (9).

Daniélou’s reference to the pitfalls of Western music is likely to be misunderstood if it is taken in a simplistic way. In fact, when he speaks about the clear expression of the highest ideas and feelings, he actually points to something quite different from what Western readers might be prone to interpret, something that is at the antipodes of an expressionist affirmation of sublime intensity (10). A possible key to understanding this aspect seems to be given in Daniélou’s explanation of the two main approaches in the Indian theory of sound: mārga (directional) and deśī (regional): the first is a “systematic application of the universal laws of creation common to sound and other aspects of manifestation”, whereas the second is based on “the empirical usage of physical peculiarities in the development of sound” (11). The expression of human feelings and passions belong to the second type of approach. The mārga approach is based on a very complex metaphysics of vibration and sound according to which the perceptible quality of sound – a quality audible to the rudimentary ears of normal human beings – is only the gross level of a much ampler spectrum. This very aspect of the Hindu metaphysics of sound is related to Daniélou’s affirmation of the higher expressive value of modal over harmonic music. The reason for his affirmation concerns the absence of physical frictions between different sounds (something that make all types of musical relations possible) and of course the expressive value of intervals. Although the modal system offers a more limited number of possibilities of producing considerable sound masses, it turns out to be much more powerful than the harmonic system because of the infinite combination of expressive intervals it allows. In spite of its magnificent descriptive and architectural capacity, the harmonic system reduces intervals to a few neutral scales and loses in this way a kind of “magical power” still present in modal music (12).

In his epoch-making book The Golden Bough (1922), the Scottish ethnologist James George Frazer defined magic as “a spurious system of natural law as well as a fallacious guide of conduct […], a false science as well as an abortive art” (13). Understandably enough, his judgment was based on the positivistic conviction that the principles applied by the magician in the practice of his art in no way correspond to any other realm than the human psyche of that very individual (the magician himself). Inanimate nature (matter in general) appears from this perspective as something absolutely separated from and alien to energetic processes (a frequency, a vibration, an idea). Almost a century after the publication of Frazer’s book we can declare that we have gained not only some historical distance from the virulent scientific reaction of positivism against any theory challenging the logic of reductive causality, but also deeper and clearer glimpses into the complexity of reality (including a drastic revision of the notion of matter in Western classical physics). In this sense we can say that scientific denial of meta-empirical correspondences has proven to be almost as unilateral and prejudiced as the superstitious expansion of physical phenomena beyond every logical and coherent frame. Daniélou’s recourse to the integral approach of Hinduism can be seen as an attempt to avoid extremes (unbounded superstition and scientific dogmatism) and try to understand the enigmatic tissue of being called “reality”, beyond the veil of prejudice. In this sense mythology, metaphysics, aesthetics and science are not to be seen as separate compartments with no connection whatsoever. Quite the contrary: human beings should work on the interstices of those seemingly independent fields and find analogies and correspondences. In Daniélou’s view, there is a phenomenological side to the magical power of music which can be described quite accurately, for example by considering the effect of modal music on the human ear: expressive intervals belong to the same tone during the execution of a rāga. The human ear associates the tone with the corresponding expression, since it is permanently affected in the same way. What from the point of view of harmonic music might be seen as monotonous and boring – i.e. the establishment of a fixed sound or tonic to which all the sounds of the melody are bound (14) – turns out to be something very powerful on the level of a perceptive and emotional effect. How far can this effect extend in the case of human reception and how transformative can it be for the listeners?

In his treatise on musical scales, Daniélou gives an answer to that question: “Our ears can apparently be satisfied by a very approximate accuracy. Yet a perfectly accurate interval not only acts on our ears but also produces a transformation in all the cells of your body – a slowing down or an acceleration in the movements of every molecule in ourselves and in the surrounding matter” (15). Lewis Thompson seems to confirm this view when he writes (after listening to a 5th on Daniélou’s vina): “I now understand that there is a physiological base for the remark of Hindus about the confused nature of Western music” (16). Confusion means for Thompson subjective (mental) projection, whereas the physiological aspect refers to an ability to refine perception and thus avoid falling back into emotional abstractions, since refined perception goes far beyond limits considered to be “empirical”. In a similar fashion Daniélou quotes an Indian mystic of the XV century, Kabir, when he introduces the subject of “pure sounds” in his treatise on musical scales: pure sound is absolute, “inaudible music”, as Kabir points out. It “cannot be perceived by our ears”, but it may “be perceptible for more delicate musical instruments” and is at the same time “one of the stages in the practice of yoga” (17). The last aspect of Daniélou’s remark is central, since it relates on the one hand the highest speculative exposition of the manifested order of the universe as a mutual correspondence between a principle of naming (the praṇava ōm) and a principle of forms (the generation of the world as jagat – “that which moves”) (18), and on the other hand the highest stage of perceptual experience within the yogic path, that is the moment when the yogi surpasses the limitation of sound perception in terms of the effect (i.e. separated result) of a previous movement or friction on the level of matter (19). Sound is in this sense not only a perceptible quality, but something intrinsic to the primordial level of vibration. From this perspective of the mysterious intertwining brahman-shakti, the dynamics of the universe appears as something different from a multiplicity of fragmented beings in permanent and chaotic expansion, and the evidential aspect of a harmony of the spheres alluded to in Indian classical music lies in the refinement of perceptual experience. Music appears in this sense not only as the possibility of bridging the gap between the physical and the metaphysical, but also as a particular form of spiritual education, whereas yogic sādhanā reveals itself as belonging to the sphere of arts and restitutes an aesthetics of the spirit beyond mere subjectivation techniques. This particular kind of aesthetics encompasses many levels and even goes beyond what is normally understood as “artistic existence”; it includes the sphere of spiritual self-realization. That was both Thompson’s and Daniélou’s view, as the former writes in a journal entry dated 22.II.1944: “[…]as Daniélou agrees, a poem that is more than cerebral condenses into seed or yantra from almost endless possibilities for whose truth it is the key; and the poet need only have felt one of them directly. If he fully knew what worlds or beings fulfill or represent themselves through his work, he would be a yogin, not a poet at all” (20).

Lewis Thompson’s sublime drama is directly proportional to his ambition: being a poet, he wanted to become a yogi. He knew that this could be attained only by absolute perception, and that any other way was a mutilation of Nature. This was the paradox of his artistic life: to know that the human experience of perception involves – to a greater or lesser degree – an interaction with the “faculty of division” called mind (manas), and at the same time to be aware of the “demonic character” of every method of suppression aiming at neutralizing the exercise of division, the fragmentariness of experience itself – including Buddhism and Advaita Vedanta (21). The way to absolute perception can sometimes block the very capacity to perceive and render any expansion dynamics impossible. Within the sphere of objective arts, this mutilation can be observed in those orderly and integrated constructions whose essence contains nothing other than convention, which fall apart at the very moment in which they collide with the intensity of life. As opposed to this, organic poetry must be – according to Thompson – “pure mantra” (22): a form retracing its steps to the source of all meaning – prior to the very division between substance and form, between sense qualities and ideal patterns. The similarities of this conception and Daniélou’s remarks on absolute sound in his work on musical scales are evident. However, there is a difference in their attitude toward the problem: Daniélou points to the constitutive (and paradoxical) value of the imperfect constitution of both the world and human beings in experiencing creation as a kind of perception – and testimony – of diversity: “if the world were perfect it would immediately be reabsorbed into the infinite perfection. The heart is not in the center of the chest, the axis of the earth is oblique, and the solar year does not coincide with the lunar year […]. In the same way the development of twelve fifths, instead of bringing us back precisely to the octave, leaves a difference – the comma – with which we shall have to negotiate. This will complicate every calculation and prevent us from formulating those rigid and simple laws, attractive but inaccurate, in which our vain reason delights. This comma […]represents […]the essential difference between what is finite and what is infinite” (23).

Thompson’s quest for self-realization prevented him from accepting the existence of the “musical comma” – even if he could permanently feel it –, and that is perhaps one of the reasons for his tragic end: he was consequent with his conviction that the problems of poetry can never be literary, because “Poetry in its roots nature belongs to the Spirit, and to Yoga” (24), but this sense of belonging required an exercise of self-denial and even self-annihilation as individual – even when the only channel for the energy to reveal the real nature of reality to reality itself is the imagination as the “natural flexibility of the psychic” and “continual renewal” (25). One wonders whether Thompson could have followed the direction of playful imagination and accepted it at the same time as the “seed of enlightenment”, doing justice to what he calls his “own nature”. This might have been a lesson in Daniélou’s practical philosophy of life, as the poet himself confirms in an entry dated 30.IX.1944: “I should learn the fundamentals of Indian music. […]This would give form, presence and consciousness to something in my nature, too, a psychic sonority, which already, sometimes, is inclined to sing and dance, the element, perhaps, that made Daniélou say I look like a minstrel, but which at present only, so to speak, floats around me and remains oblique” (26).

Notes:

(1) Thompson died in 1949 – at only 40 years old – of sunstroke in the scorching summer of Varanasi.

(2) ”Sometimes wandering monks would ask us permission to stay in the lower rooms of the palace, directly facing the Ganges. They usually remained a few days, meditating. One of them, a young man from the south, stayed nearly two months. We used to take flowers to him for his puja; he would go out and beg for his food“ (Alain Daniélou, The Way to the Labyrinth. Memories of East and West, New York 1987, p. 126).

(3) ”Alain Daniélou brought me medicine, found me unbathed in a dusty room (no water, no servant) and took me off to Rewa Koti”. Richard Lannoy (ed.): Integral Realist. The Journals of Lewis Thompson, Volume Two: 1945-1949, Virginia 2009, p. 112.

(4) Lewis Thompson: Journal of an Integral Poet, Volume One: 1932 to 1944, edited with an introduction by Richard Lannoy, Virginia 2006, pp. 391-392.

(5) Lewis Thompson, Ibid., p. 392.

(6) Lewis Thompson, Ibid..

(7) Alain Daniélou: Introduction to the Study of Musical Scales, London 1943.

(8) Alan Daniélou: Music and the Power of Sound. The Influence of Tuning and Interval on Consciousness, Rochester: Vermont, p. 121.

(9) Alain Daniélou: Ibid., p. 122.

(10) Which is what Thompson connected with the gipsy canto of Manuel Villejo: “Pure passionate intensity, direct as seed or blood“ (Lewis Thompson: Journal of an Integral Poet, p. 391).

(11) Alain Daniélou: Music and the Power of Sound, p. 59.

(12) Alain Daniélou: Origines et pouvoirs de la musique, Paris 2003, p. 48.

(13) Sir James George Frazer: The Golden Bough. A Study in Magic and Religion. Part 1: The Magic Art and the Evolution of Kings, Volume 1, London 1936, p. 53.

(14) Alain Daniélou: Origines et pouvoirs de la musique, Paris 2003, p. 57.

(15) Alain Daniélou: Music and the Power of Sound, p. 8.

(16) Lewis Thompson: Journal of an Integral Poet, p. 392.

(17) Alain Daniélou: Music and the Power of Sound, p. 4.

(18) In this respect Daniélou relies on Swāmī Karpātrī’s essay on the fundamental interdependence of sounds and forms, Śabda aur Artha (in: Siddāhnt, 1. 45, Varanasi 1941), cf. Alain Daniélou, Ibid., p. 3-4.

(19) One cannot avoid thinking of the meaning of the expression nāmnānāhatasaṁjñakaṁ in the description of anāhata chakra belonging to Purnananda’s Ṣatcakranirūpaṇaṁ, verse 22, where an allusion is made to śabda-brahmamaya, that is “sound whose substance is brahman”, produced by no cause (ahetuka) (cf. Arthur Avalon (ed.): Tantrik Texts, Volume II: Shatchakranīrupana and Pádukápanchaka, edited by Táránátha Vidyáratna, Delhi 2003, p. 30.

(20) Lewis Thompson: Journal of an Integral Poet, p. 393.

(21) Few testimonies are so sincere and radical as the following reflection contained in the entry of 25.VIII.1940: “it is only the cruel, demonic mind (Buddhism, Advaita as philosophies) that would override the heart’s love of charm and beauty. But this abstract equality prematurely forced upon a hierarchical manifestation only blasphemes the whole meaning of creation, and by sterile spiritual pride would seek to deny one’s place in it” (Lewis Thompson: Journal of an Integral Poet, p. 229).

(22) Lewis Thompson, Ibid.

(23) Alain Daniélou: Music and the Power of Sound, pp. 7-8.

(24) Lewis Thompson: Journal of an Integral Poet, p. 229.

(25) Lewis Thompson: Journal of an Integral Poet, p. 449.

(26) Lewis Thompson: Ibid., p. 446.

LIFE AND ART, by Madhavi Gore

Madhavi Gore: artist

We had been conducting workshops for a few years together, Nikhil Chopra and I, mainly with college-level art students in Mumbai and Kashmir, and also, on occasion, with students in Berlin, La Rochelle in France, and other places outside India during similar artist-residency invitations. The aim of these workshops is to introduce students to new practices within the visual arts in five- to ten-day planned academic interventions and interactions. The idea of the body as an archive of embodied memory, as site, medium and material is introduced. We want young artists in zones of conflict like Kashmir (political unrest) and Mumbai (sensory overload) to exert their talent as artists. We are clear though, this is not art activism or art therapy, it is a curricular intervention. We begin with seeing and drawing exercises, and move on to creating found-object sculptures, move off-campus into the city-streets and have a walk-about while students discuss the possibilities of public performances in highly-policed locations. Such significantly successful workshops in Srinagar were generally self-funded, with some support from the premier non-profit arts organization based in New Delhi, KHOJ.

Jana Prepeluh, a traveller, a dear old friend, and fellow performance artist from ex-Yugoslavia and India, introduced us to La Pocha Nostra’s Live Art Lab (Exercises for Rebel Artists: Radical Performance Pedagogy (Routledge, 2011) co-authored by Guillermo Gomez-Peña and Roberto Sifuentes), which she had recently attended in her hometown, Ljubljana.

Of course the work of Chicano artist Guillermo Gómez-Peña, founding member of the La Pocha Nostra collective, was well known to us. Pocha is a collective of multi-cultural, multi-disciplinary, migrant ‘rebel-artists’, and it makes radical Live Art works (http://www.pochanostra.com/). Thus with Jana’s intervention we were able to incorporate their completely copy-left pedagogic module for Live Art in order to develop The ‘BodyWorkShop’, a systematic approach and a more focused engagement with the body as a primary tool of expression – as opposed to our previous workshop modules. Through a series of planned exercises, attempts are made to break out of what we understand as the ‘normal’ workings of the body, its automatic responses and coded behavioural patterns.

We proposed the first BodyWorkShop at the Sunaparanta Center for the Arts in Panjim, Goa, India, and the second at Il Labirinto at Zagarolo, the enchanted Villa that houses the Alain Daniélou Centre. Two contrasting institutions located in contrasting environments, one in urban India and the other in the Roman countryside. Of course, the participating group, the duration of workshop days and the response of each group in relation to how much ‘breaking-in’ time we needed, differed greatly. On previous occasions we worked with a variety of processes, but with the BodyWorkShop the question of how one experiences transformation as an adventurous journey was dealt with in a more intensive and decidedly non-discursive way. Tools for performance practice were offered, inhibitions were broken within the format of closed-group exercises and sensory games using props and costume items were implemented to generate heightened and hybrid states of being and becoming.

Through the Alain Daniélou Foundation we were introduced to the life and work of Alain Daniélou, and we were repeatedly awed. Our constant question was, why did the sense of adventure back in those days, in Alain Daniélou’s world, at that time without the internet, seem so spirited? To travel by road from India to Europe in the 1930’s, to be one of the first to ‘discover’ Khajuraho, to sleep in the jungles of the man-eating tiger in the first ever camper-van designed, to immerse oneself in Banaras, to study Sanskrit philosophy and Indian classical sound, having already been an accomplished dancer in the Western tradition, all that was amazing! How on earth did figures and people like Alain Daniélou achieve and accomplish so much in such a short time with so much concentration, dedication, focus, urgency? Even complex studies of dance, music, Indology… To walk through the Villa Il Labirinto was such a maze of ideas and processes! It was marvellous to see the beauty of original Khajuraho sculptures sitting alongside Daniélou’s metronomic electronic inventions and his numerous self-created bold homo-erotic paintings in a predominantly French house in Italy, luxuriating in the fine cuisine of the chef Maurizio and the tender hospitality of Jacques and Sylvain, nestled in the outskirts of Rome, layer upon layer of time found and unearthed through the ages. And, here we are now, with deliberation and meditation, in the middle of a workshop, struggling to gain access to that spirit of adventure, that baby and child within us, untainted, to shed the grips of Puritanical, or Catholic, or Hindu conservatism and religious morality of any sort, dependency on the age of information technology, to feel suppressed and repressed by and attached to the so-called ‘points of access’ that it appears to open. Why not examine nature instead, slow down, deepen one’s gaze inward? How is a fine balance between interdisciplinarity and discipline achieved? To see Alain Daniélou’s catalogue of photographs as a dancer in costume alongside pioneering bohemian greats like Nijinsky and Diaghilev, to see Burnier’s photographs, all that was transporting. Even when the world was fraught by bloody wars, ugly battles and grave oppressions of indigenous populations by colonizers, the artists were there, the brotherhood or sisterhood of artists. The nostalgic and romance of the Alain Daniélou story was set before us, re-told with delightful enthusiasm by the charming President of the Alain Daniélou Foundation, Jacques Cloarec, seducing us back into a lost time of purity in practice, angst and true search for expression that would shake-off the shackles of all that was wrong and hateful in the world.

Is it true that we have so little time these days, or have we just forgotten to sit? How does one find one’s rigor and rhythm in these times? The BodyWorkShop is a space one enters to experience transformation and self-empowerment via live art. At Villa Il Labirinto at Zagarolo, rolling in the fields where foxes strut, hugging the linden trees, being chased by bees, amongst the lyrical olive groves, produced a markedly different experience in the final performance by the participants. In Panjim we were accused of disruption by the city police and the guardians of the church. Yes, perhaps our human caterpillar masquerade in public spaces was an act of reclamation; perhaps there were hints of dissent, yet hardly a violent disruption. The BodyWorkShop attempts to ask the question: how and from what point does one begin to move, activate oneself and shed ones fears and inhibitions? If one cannot find the courage to accomplish this in everyday life (as I, too, personally catch myself smoking in the closet in front of my elders in India), one can give oneself so much artistic license and freedom in spaces where transformation is approved, within the spaces of performance, aesthetically transformed into morphed identities that draw attention, yet also help us slip through the cracks, where body and mind align and converge. In the “here and now” of becoming is the point of rupture.

We were very pleased to be the first in the workshop series at the Villa Il Labirinto! Thank You!

THE MANY ASPECTS OF THE DIVINE, by Sarah Eichner

Sarah Eichner: Alain Daniélou Foundation research and intellectual dialogue

Remarks on Daniélou’s critique of Monotheism in the light of primordial Androgyny

“Divinity can only be reached through its manifestations, and there are as many gods as there are aspects of creation. The gods and the universe are two aspects (…) of an indefinite multiplicity.” (1)

“The initial principle can be conceived of either masculine or feminine, as a god or as a goddess, but in either case it concerns an androgynous or transsexual being.” (2)

In the first chapter of his autobiography The Way to the Labyrinth, Alain Daniélou tells us how he came to discover the divine dimension of reality in his early childhood. The context of this experience may contribute to an understanding of Daniélou’s deep and lasting conviction that the divine is not to be found outside the horizon of worldly experience but rather in the multiplicity of the cosmic manifestation and within the field of concrete experience. So it was neither the church nor the temple, but the lonely forest (worshipped in many cults as a sacred place and considered the dwelling place of the gods in different cultures) that exercised a magical influence on Daniélou as a child and where he experienced his initiation into a hidden level of reality: “Here, alone I could sense a mystery far greater than that of the ordinary human world. I created small sanctuaries and adorned them with sacred objects, symbols of the forest gods (…) through which I could communicate with the higher mysteries” (3). Not only the creation of that sacred place of his childhood, but also the painful experience of its desecration at the hands of his parents was essential for Daniélou’s further journey of self-discovery. Because of their own fixation on the presence of Christian relics, Daniélou’s parents overlooked the integral significance of the place and gave the four-year-old child the first hint of their one-sidedness in linking his religious sensibility exclusively to Christian iconography: “They found the crosses and the images of the Virgin, paying no attention to the pebbles. Now they had to consecrate this small doomed saint. (…) All this left me sad and indifferent (…). I already sensed that the religion of men had nothing to do with the divine reality of the world” (4).

This ostensible misunderstanding, to which Daniélou refers in his autobiography, may explain a whole series of prejudices on the part of monotheism when it confronts the polytheistic intuition existing in many archaic cultures. One of the main characteristic of these cultures is recognition of divine entities in the most diverse forms and aspects of cosmic manifestation (sun, moon, trees, stars, etc.); in other words: the recognition of nature in the broad sense of the word (animals, plants and also minerals) as a numinous reality and the development of forms of worship according to varying feelings in apprehending the numinous. While monotheistic one-sidedness affirms the singularity and exclusivity of only one god, the polytheistic vision displays a limitless openness to the divine and its different forms of worship. Daniélou’s experience expresses in this sense not so much the discovery of a “supernatural” instance that lies beyond nature – something cut off from the world of human beings and things – but rather a very special sensitivity for a world that is more than just human (5), a mode of perception closely related to mystical participation with the whole of the cosmic reality.

If we consider the evolution of homo sapiens, polytheism seems an inherent component of our nature, since it reflects the experience of human beings in contact with their natural environment. As opposed to it, monotheism must be seen as a very late form of religious experience taking place only in a very small part of the world. Precisely for this reason monotheistic traditions are always drawn to a kind of self-defence against the natural human tendency (clearly observable in archaic cultures and still present in modern forms of worship) of relating functionally to different numinous entities (6). What characterizes monotheistic religions is a negative demarcation from polytheism, a kind of denunciation consisting in an affirmation of their own superiority over polytheistic creeds and, at the same time, laying emphasis on the pitfalls and problems existing in cultures with identifiable polytheistic tendencies (7). But since polytheism represents a human and cultural norm of evolution, it doesn’t need any drastic self-definition in terms of demarcation – as its counterpart does (8). In this sense, polytheism is a construction of monotheism rather than a positive self-determination of the cultures associated with it. From this perspective, polytheism can be seen as a delimitation concept, the function of which is to sustain monotheistic self-understanding by providing an “image of the enemy” as “the incarnation of falsehood” – thus feeding the self-affirmation impulse crystallized in the one, unique, omnipresent and superior god. However, the question arises as to whether the interpretation of a multiplicity of divine essences related to polytheistic conceptions is not more capable of doing justice to the diversity of cosmic phenomena and human dimensions of experience, respectively nature in general (embedding human nature) as multiplicity and totality.

According to Daniélou, monotheistic religions are a “projection of the human individuality into the cosmic sphere, the shaping of ‘god’ to the image of man” (9). He draws attention to the danger of postulating one single god as absolute and elevating it above all other deities, since this attitude lays the foundations of intolerance and enmity by denying the specific cultural (and thus limited) character of the deity in question to the detriment of all the coexisting others: “Intolerant, the so-called ‘only god’ is, in fact, only the god of one tribe. Monotheistic religions have served as an excuse for persecutions, massacres, and genocides; they fight each other to impose the dominion of their heavenly tyrant on others.” (10) Since for monotheism there is only one truth, there can also be only one true belief and only one true culture, which is why monotheism in its very core demands an extreme form of ethnocentrism. The projection of monotheism Daniélou describes is not only dangerous but also very partial and biased. This becomes evident mainly in two aspects.

The first aspect concerns monotheistic reduction: as a creed, monotheism means a reduction of the natural multiplicity of gods to only one. Within the frame of polytheism, the divine encompasses all aspects of creation, while at its centre takes place the reintegration of creation in the sphere of the divine and of the divine in the sphere of creation. This reintegration occurs above all on the level of concrete experience. Human beings have direct access to the divine sphere, and since human experience is varied by nature, the divine itself appears as manifold. Different personalities and modalities of experience lead to encounters with different gods, each having specific attributes. If human beings remain at a safe distance from the constraints of a monotheistic creed, they experience the fullness of the numinous dimensions, and such dimensions are not static: they vary in form and content according to the levels of individual development. This variability produces a higher degree of freedom and acceptance in the face of the other(s): “The seeker chooses at each stage the deities and rites which are within his reach as he progresses on the path that leads toward liberation (…) He is constantly aware of the coexistence of different approaches to divinity, suitable for people at stages of realization different from his own” (11).

The second aspect has to do with the effect of monotheistic reduction: the separation between creator and creation – the consequence of which turns out to be a desacralization of the earth, nature and human beings (as part of nature). In fact, the scope of the problem Daniélou refers to with regard to monotheism does not only concern the point that human beings create God in their own image. There is something still more problematic: human beings create only a partial and one-sided image of themselves as God, in so far as the gender attributed to God is only the male aspect of the divine. The complementary image of heaven and earth, which can be found in quite a number of cultures, becomes in the frame of a monotheistic religion a one-sided preference for the upper half of the cosmos (“heaven” as the only seat of God and the divine sphere) and a dissociation of the lower half (the female “earth”, which is degraded to a place of evil). Considered negatively, monotheism is an aberration: the removal of the mother from the divine couple and the enthronement of the father as representative of absolute power (12).

Some early cultures (among which the Chinese constitutes a very special case) understand the creation process as the result of a permanent erotic and sexual union of complementary deities. In the Yijing (Book of Changes) this union is exemplified as a sign structure consisting of weak (yin) and strong (yang) lines. The sign kun ![]() (the earth) consists of six divided yin-lines and symbolizes the vagina; its movements are therefore opening and closing. The sign qian

(the earth) consists of six divided yin-lines and symbolizes the vagina; its movements are therefore opening and closing. The sign qian ![]() (heaven), on the contrary, consists of six undivided yang-lines und symbolizes the phallus; its movements are respectively contraction and extension. From a microscopic perspective, the cosmic play as a dynamic whole is presented in the 64 hexagrams of the different junctions and copulations of earth and heaven, yin and yang. It is from this intermingling and polar complementarity that the myriad things come into being. Their permanent union constitutes the gateway of change: “The constant intermingling of Heaven and Earth gives shape to all things. The sexual union of man and woman gives life to all things. The interaction of one Yin and one Yang is called Tao (the Supreme Path or Order), the resulting constant generative process is called ‘change’. ” (13) During sexual union, the order of heaven and earth is preserved and the divine play that creates cosmic diversity realizes itself. In a passage of his book Shiva and the Primordial Tradition entitled “The Monotheistic Error”, Daniélou describes sexual union as the most immediate mode of experiencing the divine: “The union of bodies in the act of love, a reflection of the union of cosmic principles, is perhaps the highest, the most direct experience that we can have of beatitude, of the limitless joy that is the nature of the divine state” (14).

(heaven), on the contrary, consists of six undivided yang-lines und symbolizes the phallus; its movements are respectively contraction and extension. From a microscopic perspective, the cosmic play as a dynamic whole is presented in the 64 hexagrams of the different junctions and copulations of earth and heaven, yin and yang. It is from this intermingling and polar complementarity that the myriad things come into being. Their permanent union constitutes the gateway of change: “The constant intermingling of Heaven and Earth gives shape to all things. The sexual union of man and woman gives life to all things. The interaction of one Yin and one Yang is called Tao (the Supreme Path or Order), the resulting constant generative process is called ‘change’. ” (13) During sexual union, the order of heaven and earth is preserved and the divine play that creates cosmic diversity realizes itself. In a passage of his book Shiva and the Primordial Tradition entitled “The Monotheistic Error”, Daniélou describes sexual union as the most immediate mode of experiencing the divine: “The union of bodies in the act of love, a reflection of the union of cosmic principles, is perhaps the highest, the most direct experience that we can have of beatitude, of the limitless joy that is the nature of the divine state” (14).

In this context, attention is drawn to the fact that monotheistic repression of the female element goes hand in hand with a demonization of eroticism, desire and everything related to human instincts and drives. Both levels (the female and the erotic) are symbolically associated; the exclusion of the female element from the divine sphere thus implies an exclusion of the erotic dimension and the sensual desires related to it. This repression of the female and also the loss of sexual complementarity – the copulation of heaven and earth – also means a fundamental change with regard to the nature of opposites, which in the context of monotheism appear as absolute opposites (and therefore antagonistic). Since human existence develops between heaven and earth and both depend on their permanent union, it is quite natural to regard them as our cosmic parents. Although the relationship between yin and yang as opposites is not antagonistic in character but rather complementary and both poles are to be regarded as androgynous deities instead of forms merely corresponding to the categories “male” and “female”, the model of the couple “heaven/earth” produces an asymmetric dynamic of forces in which (in the case of the Yijing) heaven (yang as the male principle) becomes dominant and the earth (yin as the female principle) is subordinate. A significant reason for this seems to lie in the interpretation of the polar relationship based on a heterosexual model, by means of which the originary androgyny of the divine (which should actually be the starting point) and a number of sexual means of self-development, especially the homoerotic, are ruled out from the very beginning.

While polytheistic interpretation of the divine (based on the primacy of the many over the one) is able to do greater justice to the variety and diversity of (human) nature and its dimension of experience than the assumption of a unique god and also of only one gender, and that, compared to monotheism, polytheistic intuition offers more variability as well as equality of values in general, the relationship between male and female attributes as in the very well-known model of the divine couple is not necessarily to be seen as equal and variable. Transferring the primordial androgyny of the divine, which is found in the union of cosmic principles (in Hinduism Dyava-Prthivi or Shiva-Shakti, in the Yijing heaven and earth), into a heterosexual model of human relations is a problematic reduction of sexual diversities. This reduction does not only imply the repression of the female but also the subjugation of every polymorphous form of desire under a single model of normativity. In this sense, it is important to understand Daniélou’s insights into the androgyny of the divine as they appear in his book The Phallus, Sacred Symbol of Male Creative Power in terms of a diverse model including all possibilities of matching both masculine and feminine qualities: female-male, female-female, male-male and male-female. This type of transference inevitably follows a binary structure on the level of the individual, but if the dissipation tendency is taken into account, a dynamics of diversity may result and, together with it, a counteraction avoiding reductive models like heterosexuality. Removal of the fixation on a reductive model of relationship and the opening to a diversity of erotic forms of relationship may contribute to expanding views on the problem of eroticism beyond a biological model of reproduction. Reintegration of the female aspect, which is generally ruled out in monotheistic religions, may lead to an integral expansion of the dimensions of experience contemplated in polytheism, i.e. to a total liberation and amplification of sexual-erotic forms of relationships.

This is also significant since no matrilineal culture known in our own times has ever adopted any form of monotheism, and there is no denying that extreme forms of patriarchal culture are closely related to monotheistic creeds. From a polytheistic point of view, monotheism is a kind of perversion, inasmuch as a religious focus on only one gender implies the reduction and even elimination of half of the spectrum of humanity and human experience (15). As opposed to this, consideration of the divine sphere in terms of a primordial androgyny – to which Daniélou in many cases refers and of which we have very clear examples in Chinese mythology and in the different images of the Hindu pantheon – might not only produce a higher degree of balance between the male and female aspects of creation but also do greater justice to the sexual-erotic diversity corresponding to the complexity of human nature and of nature in general. Nevertheless, this perspective remains problematic and demands further critical investigation.

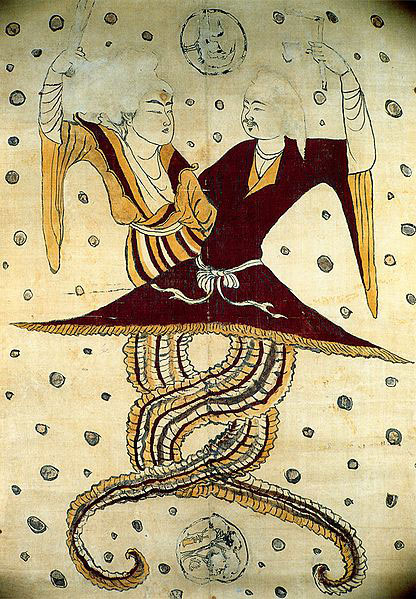

Picture of the complementary deities Fu Xi and Nü Wa (regarded as ancestors of humans) encompassed by Moon and Sun (Yin and Yang) with interwoven coloured snake tails. They hold a compass and a square (Nü Wa holds the compass, which is a male symbol of power, whereas Fu Xi holds the square, which is a female symbol of power). Both represent the order of the universe, which can only emerge through their unified work.

Notes:

(1) Alain Daniélou: The Myths and Gods of India: the Classic Work of Hindu Polytheism, Inner Traditions International, Rochester, Vermont, originally published: Hindu Polytheism, Bollingen Foundation 1964, p. 9.

(2) Alain Daniélou: The Phallus: Sacred Symbol of Male Creative Power, transl. by Jon Graham, Inner Traditions, Rochester, Vermont 1995, p. 88.

(3) Alain Daniélou: The Way to the Labyrinth, Memories of East and West, transl. by Marie-Claire Cournand, New Directions Book, 1981, p. 5f.

(4) Alain Daniélou: The Way of the Labyrinth, p. 6.

(5) David Abram: Im Bann der sinnlichen Natur, Die Kunst der Wahrnehmung und die Mehr-Als-Menschliche Welt. (The spell of the sensuous), übers. v. Matthias Fersterer u. Jochen Schilk, Klein Jasedow, 2012, p. 32.

(6) Jordan Paper: The Deities are Many, A Polytheistic Theology, State University of New York Press, 2005, p. 2f.

(7) Cf. Jordan Paper: The Deities are Many: In his book Jordan Paper develops a hermeneutics of polytheism from a comparative perspective: “A sympathetic rendering of the hermeneutics of polytheism may be some value to a hopefully more tolerant contemporary Western civilization in gaining a non-pejorative understanding of non-Western traditions”. (p. 5)

(8) Jordan Paper: The Deities are Many, p. 104.

(9) Alain Daniélou: The Myths and Gods of India, p. 10.

(10) Alain Daniélou: Shiva and the Primordial Tradition, From Tantras to the Science of Dreams, transl. by Kenneth F. Hurry, Inner Traditions, Rochester, Vermont, 2007, p. 4.

(11) Alain Daniélou: The Myths and Gods of India, p. 9.

(12) Jordan Paper: The Deities are Many, p. 21.

(13) Yijing, translated by Van Gulik, in: Sexual life in ancient China, Leiden, E.J. Brill, 1961.

(14) Alain Daniélou: Shiva and the Primordial Tradition, p. 5.

(15) Jordan Paper: The Deities are Many, p. 126.

INDIAN TELEVISION: A FAMILY AFFAIR, by Himadri Ketu

Himadri Ketu: Hindi teacher at the University of München

A still from a popular Indian soap opera Sath Nibhana Sathiya (Fulfil this Companionship) on Star Plus

Indian television, one of the huge industries of the country, occupies the third position in the world market after the USA and China, with more than 823 channels and millions of faithful viewers. With thousands of programmes broadcast in many languages, Indian television rules the heart of its audiences and is the most popular medium of entertainment for Indian families. A survey conducted by Jaspal Singh and Namrata Sindhu What interests the Indian Television Audience: An Empirical Study (2011) reveals the popular and unpopular television programmes among Indian audiences. The five most popular programme categories are soap operas, infotainment, news, reality shows and movies, whereas the five most unpopular are teleshopping, travel shows, supernatural thrillers, programmes for children and sports (both categories mentioned in descending order of popularity). The survey showed a slight deviation from the TRPs (Television Rating Point), according to which historical/mythological programmes are always among the most popular top five. The fact that remains unchanged in both cases is that soap operas dominate the Indian small screen and are viewed by families in urban as well as rural areas. Indian soap operas are a colourful amalgam of melodramatic emotions, perfectly fitting the description by Alessandra Stanley, chief television critic of The New York Times, “Speed-clicking the remote after 8 pm is like watching a Power Point display of passion in hot pink, glimmering tears and the occasional stinging slap across the face” (The New York Times, 2012).

For a better understanding of the phenomenal success of soap operas on the small screen, I shall first of all go briefly through the history of Indian Television. India began broadcasting in 1959 through its state television network ‘Doordarshan’, the only network available at that time. “Doordarshan’s programming carried educational messages that addressed such development themes as health, family planning, adult literacy and agricultural development” (Malhotra; Rogers 2000: 408). In 1984, telecommunications minister Vasant Sathe, inspired by soap operas in Mexico, introduced this type of programme both to educate and entertain the public (Lecuyer 2013). Hum Log (We the People), the first soap opera with themes such as sexual equality and national integration, was broadcast for the first time on 7 July 1984 on Doordarshan and it soon became very popular among the masses. Following the success of this soap opera, two mythological serials, Ramayana and Mahabharata – both based on the Hindu epics – were launched on Doordarshan. These audio-visual adaptations of great Indian sagas were huge hits due to their “familiarity and subject of religiousness” (ibid.). The serials were worshipped by their Hindu spectators and perceived as a religious experience. “The actors became cult figures, indistinguishable from the gods whose roles they were playing, since darshan, a concept fundamental to Hinduism, sees divinity as existing within the very image representing it” (Deprez 2009: 425). Even pujas were organized when these serials were broadcast on Sunday mornings and everyday life came to a standstill to watch the shows. The dramatized versions of Indian epics brought millions together beyond cultural and linguistic diversity and set a still unrivalled viewership record. Our generation of the 1980s has grown up with both these serials and I can vividly recall the reverence we all had for these myth-based programmes.

In the 1990s Doordarshan allowed private companies to produce fiction-based programmes for prime-time broadcasting. With the launch of STAR TV (Satellite Television for Asian Region, a privately owned network in Hong Kong) in 1991, the commercial television industry in India was established. Fully aware of the big market and success of the commercial industry, private companies launched their own Indian networks from 1992 to 1996. (Malhotra; Rogers 2000). The transmission of American soap operas through satellite programmes and their successful reception by urban audiences inspired Indian producers to make their own soap operas in order to attract a larger audience in both urban and rural areas. The arrival of soap operas (the so-called family tales) on the Indian television landscape, pushed mythological shows down the popularity chart, although mythology still enjoys the status of a favourite television genre among Indian audiences. Private channels produce many serials based on the Hindu gods, but have not been able to match the success of Ramayana and Mahabharata. The cartoon serials describing the life of Krishna and Ganesha were originally aimed at a mainly juvenile audience, but came to be watched by the whole family.

Soap operas brought a new trend to television programs and changed the whole televisual landscape. In a country like India, where the concept of the extended family is still the ideal one, it became the centre of all soap operas. Family relations and conflicts, especially conflicts between mother-in-law and daughter-in-law, became the backdrop of all serials. The major cable and satellite networks (Zee, Sony and Star) air soap operas all day for Indian housewives who make up the largest viewership for such shows. The boom in regional channels has resulted in more Saas-Bahu (Mother-in-law – Daughter-in-law) serials in regional languages with socio-cultural specificity for the particular region.

The Indian production company Balaji Telefilms has set a standard concept for television serials. Since 2000 it has produced many serials and turned housewives into heroines with stories based on conservative lines (Lecuyer 2013). The serial Kyunki Saas Bhi Kabhi Bahu Thi (The Mother-in-law was once a Daughter-in-law too) produced by Balaji Telefilms is the longest-running serial (2000-2008) in the history of Indian television. The super-hit Saas-Bahu formula has been copied by other production houses and turned into innumerable soap operas telecast in the evenings from Monday to Friday and on some channels even on Saturdays, and are repeated once or twice a day. Consequently the whole family sits together in the evenings and watches the show, making it a genuine family affair.

“Soap operas here are outlandish — some so stylized and wildly melodramatic that they verge on camp. But they are also oddly prosaic; expressions of duty, deference and parental obligation that inform everyday lives” (The New York Times, 2012). Soap operas that create identifiable characters for viewers, with values such as self-sacrifice and respect for elders, are highly popular: these middle-class values are paradoxically propagated by displaying a wealthy family living in a mansion with women draped in expensive traditional saris and jewellery. Lecuyer characterises the female figures of serials as personifying the qualities of Helen Keller and Mother Teresa, since the female protagonist always sacrifices herself for her family’s happiness and suffers in silence. The actresses Ankita Lokhande in Pavitra Rishta (Sacred Relationship) on Channel Zee and Devoleena Bhattacharjee in Sath Nibhana Sathiya (Fulfil this Companionship) on Channel Star Plus are exemplary daughters-in-law, standing out as the most loving and forgiving characters in the serials. Such stereotypical characters are repeatedly shown in every soap opera and are adored by the public. The stars of the small screen are household names and enjoy great popularity no less than big screen stars.

Soap operas receive a lot of criticism for being conservative and regressive in their subjects. Independent and ambitious women are generally shown as negative characters who bring harm to the family. Some channels have broken the trend of traditional family sagas and their soap operas have themes bringing social awareness to the viewers, such as Balika Vadhu (Child Bride) on Channel Colors, a soap opera that discourages the Indian practice of child marriage. Some such serials have been received well and achieved their purpose, but most of them returned to the same old formula for fear of losing TRPs. The article Satellite Television and the New Indian Woman (2000) argues that Indian programmes revert to traditional gender roles and at the same time try to break out of them in other ways. The popularity of women-based programmes and the diversity of gender-role constructions indicate a positive step towards construction of such roles. The report of the National Bureau of Economic Research (2007) studied the effect of satellite television on gender attitudes and came to the conclusion that its introduction has improved the status of women, especially in rural regions, and as a result of that has brought about some positive changes: it has increased women’s autonomy, female school enrolment and has reduced son preference.

Even mythological serials have adapted to the contemporary style of soap operas and also deal with issues relevant to society. The serial Devon ke www…Mahadev (Lord of Lords…Mahadev) based on the legend of Lord Shiva was launched on Channel Colors in 2011, and Mahabharata on Channel Star Plus in 2013. Both were an instant hit due to the change in the narrative mode. Contemporary issues such as parenting and honouring women as well as essential human values such as love, arrogance and hatred are included in the narratives (Business Today 2014), again helping to win audience ratings.

A still from the mythological serial Devon ke www…Mahadev (Lord of Lords…Mahadev)

The relevance of Indian soap operas and mythological serials remains debatable, but their popularity in India and even abroad among the Indian diaspora is undeniable. Soap operas with tricks such as double roles, jumping a few years, keep introducing new characters into the serial to make it more interesting, so that serials now run for years on end. Soap operas have become an integral part of the life of middle-class families, and generations grow up on them.

Bibliography:

» Awaasthi, Kavita (2013): Mythological shows a hit on TV. In: Hindustan Times, 22.04.2013

» Deprez, Camille (2009): Indian TV serials: between originality and adaptation. In: Global Media and Communication, Vol. 5, No. 3. 425-430

» Jensen, Robert; Oster, Emily (2007): The Power of TV: Cable Television and Women’s Status in India. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 13305

» Lecuyer, Helene (2013): Soap operas dominate prime-time television in India. In: Ina Global, 16.05.2013

» Malhotra, Sheena; Rogers, Everett M. (2000): Satellite Television and the New Indian Women. In: International Communication Gazette, Vol. 62, No. 5. 407-429

» Moorti, Sujata (2007): Imaginary Homes, Transplanted Traditions: The Transnational Optic and the Production of Tradition in Indian Television. In: Journal of Creative Communications, Vol. 2. 1-21

» Shashidhar, Ajita (2014): Grace of God. In: Business Today, 19.01.2014

» Singh, Jaspal; Sandhu, Namrata (2011): What Interests the Indian Television Audience? – An Empirical Study. In: Asia-Pacific Business Review, Vol. II, No. 3. 134-145

» Singhal, Arvind; Rogers, Everett M. (1988): Television soap operas for development in India. In: International Communication Gazette, Vol. 41. 109-126

» Stanley, Alessandra (2012): On Indian TV, ‘I Do’ means to honor and obey the mother-in-Law. In: The New York Times, 26.25.2012

INFLECTING THE FOREIGNER’S DISCOURSE, by Samuel Buchoul

Samuel Buchoul: writer, editor and designer of LILA Foundation (New Delhi)

Every discourse requires an inward reminder, a word of caution, a self-warning. What is the background, the hidden context of a reflection? The foreigner, this foreigner, and his voice, must step down from the podium of philosophy proper to dare the ‘I’, anxious that he might stumble into the pitfalls of a philosophized diary. But this is necessary: to legitimize bending forward – the reflection – the precaution of a bending inwards is required – an inflection. As a compromise to secure, through barter, the philosophical digressions of outrageous generalizations, this voice, the familiar, ideal, universal anonymous voice of the written, acknowledges its identity as my voice. Native French of the late 1980s; a short exchange programme in the USA two decades later; and residence in India for the last six years and still on-going – three in the capital, two in a small university town of the western Deccan and now back in Dilli. Sufficient introduction.

What is this foreigner talking about? The lucky owner of a lenient timetable, and subjected to no pressing financial needs, the foreigner finds himself turning into a full-time, large-scale secret ethnographer. Without even the pressure of having to come up with scientific results. The curious mind, still under the high of this enigmatic cultural discovery, takes every occasion to keep eyes, ears and lips wide open, and every slow evening or calm Sunday to gather observations and attempt to write disproportionately ambitious treatises on cultures, society, religions, civilizations, politics or history. The readership is modest but faithful, enthusiastic and encouraging, behind each online publication, as rhetoric and narrative quality steadily grow. The foreigner writer is soon re-christened ‘the Indian’, an eternal enigma to him, which even his local acquaintances adopt: “You have become fully Indian now!” “You are more Indian than us!” His fragile social life back home stagnates even further, so his language of expression shifts, a few years later, in order to be understood by the locals, his new, real nears-and-dears. The regularity of his opinion pieces slows down, as his daily occupations increase in intensity, now that he is more than an observing witness – as a student, first, and later, as a working professional. Progressively less numerous, too, are the lenient excuses to justify his impatient and generalizing speculations. The foreigner is not so sure anymore.

Indeed: what could the foreigner be talking about? Reflective, existential outlines suffice for a time only; the new environment affects him too fundamentally: it must, in fact, become the focus. The foreigner-writer is happy to come slowly to see himself as a bridge, as the convenient observer and interpreter of that faraway, exotic land. A translator of the outside for his co-nationals who stayed at home, he simultaneously becomes, eagerly, but also with a sense of modesty, a dissenting and inspired voice for his local network. Coming from the outside, he kicks and slaps local standards and norms quite gracefully. Before realizing he is, in the end, only a drop in the ocean of a definitely transcending social, cultural and historical terrain.

So, what is left for the foreigner? To talk about India? To talk about ‘the Indian’, in its fantasized ideality? To talk about Indians? Which Indians? And from which angle? The question of authorship is fundamental to the foreigner becoming a resident alien. He even discovers around him, within his dual terrain of observation-action, the echo, the inward reflection of his asymmetric, hypocritical, almost schizophrenic voice. Remembering what is known in the social sciences as the Standpoint Theory, the foreigner discovers and acknowledges the local structure of sociality, noticing that, indeed, the Brahmin can and should hardly speak of or for the Dalit. There too, the pattern of the foreigner, his different background and problematic voice, are visible, but this time national borders are nowhere to be found. And the legitimacy of his initial, naïve, diplomatic-like visit seems utterly lost. Like the Brahmin, should the foreigner speak of the local? Speaking: vocalizing an ‘understanding’ of the local, i.e., reducing the latter to the limited set of concepts and feelings he has access to. At home, the epistemic challenge seemed much more accessible: first finding one’s inspiring figures, and then, choosing one’s targets, one’s opponents in today’s battle of worldviews, in order to be able to make sense of one’s country and its culture as a movement to which one somehow belonged. At home, the intellectual could live in peace, protected by the camp he decided to side with. Abroad, behind the veils warning of modesty, the intellectual project altogether seems, suddenly – to say the least – ambitious. What if interacting with the other as the other would mean precisely interrupting the intellectual project, the project of ‘knowing’ altogether? What if the foreigner stopped being foreign only once he decided that he has truly exhausted the standpoint of the foreigner?

But will this be a peaceful journey? A beneficiary of the comfortable welfare states of today’s modern European societies, this western subject is tempted to see in his taste for existentialist worldviews the intuitive proof that human existence is history-less. That the elements that make up an individual’s life are, fundamentally, independent of space and time. But the subject has a history, and in this privileged situation, perhaps only his migration and sustained residence abroad can truly remind him of this. Indeed, the newly reborn foreigner is now liberated from all that his family, surroundings and national culture expected of him. And he has proudly short-circuited the impositions of what Heidegger saw as an unbreakable existential condition: one’s thrownness, one’s undeniable initial attachment to one space and one time only. But, in fact, the foreigner is truly subject to another imposition, and one that is of a different kind: an ethical imposition. The foreigner cannot remain passive, as before, waiting in his environment to ensure his survival and much more, his self-realization. He cannot be integrated by default, as he used to be in his native land. Living cannot be taken for granted anymore.

And while all that may be true for every host nation, the statement must be further inflected to account for the historical dynamics at stake in this present scenario. In the post-colonial world, the foreigner as westerner is directly implicated, ethically speaking, in his new situation in the non-west. Perhaps due to a certain Christian heritage, the westerner’s presence in a post-colonial society starts with a sense of guilt, with a prejudice, with a deficit that he will have to balance. In the post-colonial world, the Romantic existentialist of the Old World enters history, enters the troubled waters of humanity’s bloody interactions across centuries and millennia. And at this particular juncture, the westerner in the post-colonial country owes something, comes after, always after the historical turning point of the western colonialist’s visit. Some locals differ as to the outcomes of this historical turn, and evaluate – sometimes even praise – the positive fruits of the British Raj. But, by and large, the period was more than a historical contingency – it was an invasion, an unjustifiable imposition of one’s culture and economic scopes onto the millions of lives of another civilization. Has the descendent of the invader always felt such a sense of guilt throughout history, when visiting the freshly liberated territory? Would the Ottoman soldier feel like apologizing when returning to France, decades after Charles Martel? Maybe not: at that point, the individual was viscerally aware of the necessary compromises of violence that come in making borders, in one form or the other. But, since then, the scene has changed on the surface. This violence has undergone a metamorphosis, disappearing from sight but still kicking within cultures. While the west colonized the world, its world, its very philosophers, back home, were laying the foundations of the very transformation of imperial ambition, reformulating Christian evangelism into softer and subtler forms of cultural and moral dissemination. And soon an Edward Saïd would remark the pervasive and silent, and therefore expanded western incursion through the discourses of culture, leaving its marks decades after the last governor returned home. Not to mention the massive diplomatic, military and especially economic architecture in force around and through those post-colonial societies, confirming to the foreigner not his personal implication in the contamination, or of a Manichean play of powers on passive victims, but of the true, historical implications of the philosophy of his civilization. Of, in fact, the tragic outcomes of all that he had ever benefitted from, back home. Of what, too, made possible the very comfortable conditions of his migration to the non-west, in an age when the opposite movement is immensely harder and more controlled. Thus, stepping inside the doorway of another, tangential and intersecting history, the foreigner repents, excuses his presence, his interlocution, to say: ‘I came after, therefore, perhaps, I should not have come.’ And he demands: ‘but it is your hospitality that I require, and to it, finally, I surrender’.

But generations pass, generations forget, and generations accept. And the foreigner is granted hospitality. Soon, comical episodes of street encounters or interactions with nationalist spirits remind him of the historical baggage that follows him on his prolonged visit. On the whole, the foreigner is welcomed, cherished, praised from afar, but yet, also, sometimes, treated with indifference from nearby. Still, he cannot complain, when, two or three months after stepping onto the tarmac, he ends up at the birthday party of the posh South Delhi residence of his classmate, whom he will discover years later to be the son of a scam-ridden Congress minister of commerce, turned law and justice, turned external affairs. And his drive, on the way, was guarded by six or seven security employees, spread over two SUVs – he asks the other passengers: “Is Madhav famous or something?” – chuckles. A few days later, he learns he danced the twist with the Prime Minister’s grandson. The flashing lights of a foreigner in the capital, rehash of a fantasized Paris of the 1960s where intellectual migrants could mingle with the cream of the country’s journalists, thinkers and politicians. A superficial introduction, too, years before the slow awakening of a deeper political consciousness, making him realize how, in India perhaps more than anywhere else, it is always the outside gaze that is necessary, the out-look, the reminder of the reality check, especially when it comes to national decisions made in the capital – the (urban) capital of a country only 30% urbanized. In India, outside is always bigger. The foreigner enters politics, thus, and, more: a particular branch of national politics. Second figure of the inflection.