BOOK REVIEW

CHIARA POLICARDI’S DIVINE, FEMININE, ANIMAL: A GUIDING THREAD THROUGH TANTRIC PALIMPSEST OF YOGINĪ CULTS

Chiara Policardi. Divino, femminile, animale. Yoginī teriantropiche nell’India antica e medievale, Alessandria, Edizioni dell’Orso, 2020. 290 pages with 3 tables, 65 images and a thematic bibliography.

Tinged objectivity: the ‘female thread’

Let’s suppose that scientific research is not exactly what it claims to be: an objective approach delimiting substantiated description from arbitrary speculation. Even if we grant it a ‘will to objectivity’ (which, according to authors like Paul Ricoeur, distinguishes the historian from the story-teller), we know that no will is homogeneous and straightforward – let alone transparent. The history of scholarship is a history of positions, interests, modes and strategies of power and legitimation; and sometimes such strategies betray the asymptotic objectivity envisaged by the scientific will. The inevitable tension between will-to-knowledge and will-to-power permeates the noble exercise of historical reconstruction. For the will-to-knowledge there is little or no distinction, if one proceeds ‘scientifically’, of race, gender, political orientation or subjective tendencies. For the will-to-power, on the contrary, knowledge is an excuse, and objectivity standards have not fallen from heaven, but are extracted from the conflict-laden arena of intellectual exchange. In this arena, the position – or disposition – of the researcher counts, and the more conscious he or she becomes of it, the richer the style and denser (but more unstable) the objectivity-plot.

For the Summer issue of 2017, I made an exception to the general editorial tendency of Alain Daniélou Foundation’s online publication (where book reviews are excluded) and wrote an article on Gioia Lussana’s La Dea che Scorre (The Flowing Goddess), a book published that very year. Sometime later Gioia Lussana became one of Alain Daniélou Foundation’s grantees, and her research activity and practice gave their fruits even outside academic circles. This year comes the second exception: Chiara Policardi. Her book Divino, Femminile, Animale (2020) deserves the same treatment as that of Gioia Lussana’s book. Both of them are doctoral theses. Both authors, of Italian origin, conducted their research projects under the guidance of one of the best European Sanskritists: Prof. Raffaele Torella. Both of them approach the question of female divine agency in the Hindu Tantric tradition showing a singular disposition: they are aware that their female condition cannot – and should not – be neutralized by scientific standards. They are determined to read between the lines, knowing that the eyes of a woman – when it comes to the power of the Female – cannot remain fully indifferent to the ‘object of study’ – because the object of study, in this case, is not severed from a certain ‘real presence’ and power of influence: the Goddess Kāmākhyā in the case of Lussana, the Yoginīs in the case of Policardi. This subjective marker, which can be seen as a token of arbitrariness, is actually the guiding thread in both books.

It is not about declaring devotion to a Goddess or pronouncing oneself hermeneutically vulnerable to non-human powers. George Steiner spoke of ‘real presences’ to underline the aura of Western classics (rendered invisible in poststructuralist Cultural Studies). Mircea Eliade observed a gradual change of personality in the historian of religions who deals with the sacred (something to which other authors like Raffaele Petazzoni and Ernesto de Martino seemed to be rather impermeable). In their own way, Gioia Lussana and Chiara Policardi show that a guiding thread in the Tantric territory, if it is the result of a female gaze can reveal other aspects – because another disposition is at work. Of course, these aspects will probably be cornered into the suspicious enclave of ‘speculation’, but the most important point is that the type and even the horizon of speculation inaugurated by such researchers is another. In his controversial The Psychological Stages of Women’s Development (1959), Erich Neumann points to the fact that women are naturally reconnected with the (essentially maternal) Uroboric Self in such a way that they don’t need to go through the stage of full detachment from it – as men do, disclosing the everlasting polarity between cultural achievement and neurotic symptom. Such a statement about female psychodynamics may alarm feminists who think that the only type of ratio – to be conquered by women – is what has crystallized on a cultural level out of masculine psychology, but it should interest researchers in the field of Tantric studies. This is no question of ‘essences’, but of dispositions, tendencies and ways of looking – we may add: ways of reading and experiencing. ‘Logocentrism’ is a cross-cultural feature of male dominance, but as such it cannot be eradicated, since it is part and parcel of deep-rooted intelligibility processes. Transformations should be rather silent and enduring. What should become visible are the unseen inscriptions of the cultural palimpsest we once thought homogeneous and one-stringed, and the gender optic – here to be distinguished from the hard-core political question of feminism – is a very important reference to introduce significant differences and broaden the field.

A multidisciplinary approach: doing justice to the complexity of the Yoginīs

Policardi’s book is a very solid piece of research dealing with at least three fields of knowledge not so easily brought together in a coherent manner: philology, iconography and a combination of ethnology and history of religions. In order to approach the question of these enigmatic beings within the Tantric tradition called ‘Yoginīs’, Policardi plunges into the earliest Tantric texts of Vidyāpīṭha Shaivism (where the Yoginīs are first mentioned), such as the Brahmayāmalatantra and Siddhayogeśvarīmata (both of which can be dated back to the VII century CE), as well as into the most important Kaula texts concerning the subject, like the Kaulajñānanirṇaya (between IX and XI centuries CE) and the Ṣaṭsāhasrasaṃhitā (XII century CE). This choice already bears witness to the courage of the author: apart from exegetical problems concerning the partial edition of the Sanskrit manuscripts in question and their linguistic peculiarities (esoterically upgraded by means of the emic terms aiśa and ārṣa), the earliest Tantric texts demand a consideration of their immediate past, which is that of local and tribal cults. One cannot think of the Yoginīs without bearing in mind this effaced layer of the Tantric palimpsest, but the problem arises as to how to read coherently pre-Brahmanic references of an extra-textual nature in a Sanskritized textual corpus. This aspect inevitably forces Policardi to widen her research parameters to ethnology and history of religions. In the same way, some Kaula texts, like chapter XV of the Ṣaṭsāhasrasaṃhitā, inevitably lead to an extension of the research field from Tantric to Purāṇic territory. In taking this step, the author is faced with a mythological universe interacting with ritual prescriptions and rendering visible the complex integration of marginal esoteric trends within the orthodox Brahmanic mainstream. At the same time, the Kaula corpus contains detailed descriptions of Yoginī-pūjā, whose visualization techniques introduce contents related to temple iconography. For Policardi, iconographic representations of the Yoginīs are an indispensable complement to textual sources and should therefore be integrated into the scope of her research. She courageously plunges into an analysis of the Orissa temples of Hīrāpur, Rānīpur and Jharial as well as the Bherāghāṭ temple in Madhya Pradesh. But not only that. She also bears in mind the portals of Dabhoi and Jhinjhuwada in Gujarat and, following Purāṇic traces, some Yoginī-drawings in a pictorical map of Kāśī dating back to the early XIX century. Such references permit her not only to gain a comprehensive and integral view of the hybrid beings called ‘Yoginīs’, but also to reinterpret the status and value of local deities and their subsequent incorporation into iconographic canons.

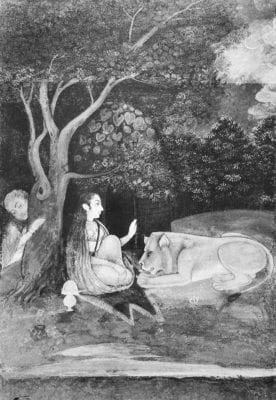

Yoginī and lion: miniature on paper; late XVIII century. Salarjung Museum, Hyderabad. Source : Dehejia, Yogini Cult and Temples: A Tantric Tradition, 1986, p. 12.

Yoginī and lion: miniature on paper; late XVIII century. Salarjung Museum, Hyderabad. Source : Dehejia, Yogini Cult and Temples: A Tantric Tradition, 1986, p. 12.This methodological decision shows how sceptical Policardi remains in the face of an interpretation of the Yoginī cult as merely based on the medieval Shaiva textual canon. Her references to the demonization of ḍākinīs in the Siddhayogeśvarīmata (26.40.), a form of subordination to the god Shiva, as well as the association of composite, fluid and forest-related beings (gaṇas, yakṣiṇīs and mātṛs) with a strong discontinuity tendency in the face of Brahmanic inclusivism reveal that she is engaged in highlighting the religious and socio-cultural value of female divine agency, not only as one more element in the Hindu medieval landscape, but also as a heterodox tissue whose potentialities still have to be displayed and could – to a certain extent – change perception of the Shakta realm.

Evasive content: fluidity and antinomic power

The question of Policardi’s approach to the Yoginīs, which I have sought to present from the perspective of method, can also be tackled from the point of view of content. Every reader will notice the problem of knowing what Yoginīs actually are; the spectrum of possibilities for any definition is so broad that it may generate a sense of disorientation or even confusion. Are they goddesses, female demons, supernatural agents, intermediate beings, forest spirits, female adepts [śakti, sādhikā], tribal witches, chakra-deities, hypostases of a Shakti-principle or symbolic supports of an ascetic imitatio animalis? Of course, each aspect, as long as it appears in (or can be plausibly deduced from) textual or iconographical sources, is valid, but instead of going into the one and the other characterization (risking an incoherent compilation of roles and functions), Policardi seeks a guiding thread by pointing to the Yoginīs’ hybrid nature, expressed in a double-bind sort of complementary duplicity: they have human and animal features; they have divine and demonic powers. This is also the reason why the author prefers to focus on the therianthropic rather than on the theriomorphic component. Such a distinctive feature of the Yoginīs is chosen not only because it has been barely researched, but also because it provides an articulation of spheres. For example, the already-mentioned divine-demonic [deva-nāraka]coupling bears an essential relation to the thematization of animal features as representing alien powers, which means that the religious content of the Yoginī cults is alien to the village [kṣetra]and rather close to the forest [vana]. In the village there is the codified pantheon, while in the forest the ‘otherness’ (in the sense of the alien or foreign: araṇa) comes to the fore – and it comes in a concrete manner, joining antithetic poles and questioning the fixity of values. Yoginīs are the ritual and mythical concretion of that otherness that humans encounter in natural settings, where conventional forms of socialization (even with divine beings) do not play a dominant role. Out in the forest, deities are not tame. Perhaps they are demons. Perhaps they are coupled with the reverse-side of the brahmanically-socialized feminine. Policardi shows that Yoginīs are the incarnation of an exteriority that cannot be objectified – since otherwise the ritual encounter [yoginīmelaka]would never take place – but has to be channelled from the very field of experience that constitutively includes it. Such an encounter, the expressions of which vary from possession [āveśa]to copulation [maithuna], vehiculates the whole power of that exteriority in the life of conventionally socialized humans.

If the fluid character encompassing the human and the non-human is essentially related to the feminine, Policardi shows that heroic status in the ritual Tantric context is ascribed to male adepts who manage to bear, channel and harness those powers. Of course, there is a considerable difference between the ritual orthopraxy of a Brahmin who separates the pure [śuddha]from the impure [aśuddha]and the antinomic practice of a tāntrika with a non-dual behaviour facing the metamorphic powers of Yoginīs or Mothers. However, if we take the liminal, fluid, transgressive and excessive character of female divine agency seriously, that distinction is relative. Policardi’s book gives the reader some hints for further reflexion on what I would call the ‘dilemma of Shaktism’. What does it consist of? If we consider the tribal roots of Shakti cults (of the type related to mātṛs and yoginīs), they transcend the textual evidence in which they are inscribed. A purely philological approach would not question the only reliable framework in which such beings come to presentation, and this is what Policardi acknowledges with citations of André Padoux on the Shaivite character of terrible female deities and Alexis Sanderson on the construction of the Shaiva canon and the characterization of Shakta variants as constitutive parts of it. However, an attentive reader will notice that Policardi highlights not only the ambivalence of Mothers and Yoginīs from the point of view of their intrinsic nature. This ambivalence is a kind of pivot around which different world-configurations rotate – one of which seems to be dominated by female agency, even when the center of the ritual maṇḍala is occupied by Shiva-Bhairava. This pivot manifests itself in expressions like siddhipradāyakā (referred to devīs and yoginīs) in the Brahmayāmalasāra (12.1b) and Brahmayāmalatantra (73.47d). That these beings have the ability of granting special powers can be regarded from two different optics: 1. As source of power to be harnessed by male practitioners (this end justifying the manipulation of the means), 2. As a sign of the expansive power of female agency permeating the universe of male dominance (and enfeebling the manipulative homogenization). Once again, the second optics does not oppose the female to the male in the way feminism opposes male domination. The expansive power of female agency means many things at the same time: first of all, the center of the ritual maṇḍala dominated by a god (as a unifying hierarchical and metaphysical principle) fades before a multiplicity of natural powers interacting with ritual practitioners. Secondly, the limits of the human and the non-human are re-defined within a non-vertical continuum of forces, that is, a spectrum in which the animal and the divine not only coexist but are also interpenetrated. Lastly, ‘logocentric’ attempts – always a result of patrilinear structures – may build structures of ‘the spirit’ (which means, at a social level, a scholastic elite), but such cultural and even soteriological refinements are incapable of containing the fluid matter of life, overflowing limits which are ultimately blurred and not at all impermeable.

Yoginīs are the ritual and mythical concretion of that otherness that humans encounter in natural settings, where conventional forms of socialization (even with divine beings) do not play a dominant role.

The dilemma of Shaktism

View of yoginī along the portico, with horse-faced Śrī Eruḍi, in foreground and pig- or deer-faced yogini.

View of yoginī along the portico, with horse-faced Śrī Eruḍi, in foreground and pig- or deer-faced yogini.Temple of Bherāghāṭ. Photo by Chiara Policardi

Policardi expresses the ‘dilemma of Shaktism’ by means of the question as to whether the cult of female deities like Mothers and Yoginīs has actually become Tantric or whether the Tantric phenomenon emerged from those practices and cults. This question may be purely speculative from the point of view of textual interpretation, but it is legitimate if we bear in mind the multidisciplinary approach followed by the author. Neither ethnology nor history of religions is any longer dominated by the standards of European humanism, according to which ritual, cultic and religious phenomena are subordinated to a normative notion of ‘high culture’ and in many cases to a teleology of secularization (the previous stage of which is scholastic metaphysics). Perhaps the most interesting aspect of Policardi’s book is that her insistence on the liminality, the otherness-character and the fluidity of hybrid beings like Mothers and Yoginīs goes beyond the usual interpretation of animals’ features as instances of symbolization – since symbolization processes are a passage from a gross (primitive, local, tribal, material and exterior) form of ritual practice to a much subtler or more refined (developed, widespread, unifying, interior and spiritual) one. Although the author makes it clear that composite deities (with intertwined human and animal features) are manifold in the classical Hindu pantheon, the relationship of Yoginīs with the tribal background of Shakta Tantra calls for an interpretation that may do justice to a world-configuration significantly different not only from Vishnuism as a recipient of devotional and personalistic forms of Brahmanic worship, but also from the scholastic systematization of different Shaiva cults. Policardi is quite aware of this. She highlights the cultural centrality of female deities, the existing bridge between their nudity [nagnarūpa]and their power of transmutation [rūpaparivartana]as well as the embodied hybridization of human and non-human as one of their intrinsic features (expressed in composite terms like kharaṅgāvasthitā, śvānāṅgāvasthitā, uṣṭrāṅgāvasthitā, etc.). Therianthropy is, stricto sensu, no representation, no symbolic instance of something that lies beyond ritual performance and cultic techniques. Were it so, the symbolic instance would have the function of ‘elevating the animal’ to something that it is not. Even if we think of the mask-like delimitation of animal faces in Yoginī temple sculptures – where the rest of the head is clearly human (for example, the hair style), they do not merely ‘symbolize’ animal-power. They express the absence of ontological disjunction between human and non-human – which can be traced back to the animistic setting of forest rituals. They de-limit, in the sense of joining and blurring ontological boundaries. As Policardi says: even if we think of these ‘masks’ as ritual tools, they do not ‘separate’ two natures (the real human and the imaginary animal) but join the human and animal elements in a logic of becoming in which the distinction between real and imaginary as we usually conceive it is not valid. Theriocephalic de-limitation of the human seems to be the ultimate consequence of the Yoginīs’ nakedness, that is, revelation of their transformative powers to the point of questioning already-established and even naturalized values – including those shaping a vertical distribution of beings.

In the Yoginī tradition, the value of the female-animal pair is reversed from a status of metaphysical inferiority to that of esoteric singularity.

Needless to say, the world-configuration that opens through the Shakta lens of the Yoginīs cannot be grasped by means of the usual diairesis between subtle and gross, transparent and obscure, beneficial and detrimental. If one considers the powers in question and their effects, conceptual devices that seem obvious become altogether questionable. This is the only point in the book with regard to which I would express a critical note of dissent. Policardi masterfully leads us into the universe of Yoginī cults to the point of showing its reverse side, and she seems to indicate that at least an important part of the Tantric tradition should be (re-)read from that reverse side. She points to male practitioners harnessing the power of female deities, but she highlights their being possessed as a sign of subordination to that female power. She points to the male standpoint in the construction of the Tantric corpus, but she does not renounce another map of reading, where the female perspective may gain the upper hand. She reverses the value of the female-animal pair from a status of metaphysical inferiority to that of esoteric singularity. Such operations indicate that many things would undergo a significant change if one were to pursue that cursory glance into the reverse-side of Tantra as śākta kulamārga from tribal domains: 1. Animal power would not appear inferior but is amalgamated with the divine in a deep horizontal structure. 2. Symbolism and internalization would not be associated with a distillation of an unmanageable prima materia, but rather with the domestication and even suffocation of specific ritual and ecstatic practices connected with natural powers. 3. So-called ‘natural’ powers would encompass what is usually called supernatural, with the fading of the notion of ‘nature’ as something substantially external or alien to (human) culture. The type of ‘culture’ arising out of such tribal elements in the cult of female deities is one in which nothing is objectified as ‘external’ – since that would mean depriving it of its power. The animal-divine is from the very beginning incorporated and elaborated in a theater of cruelty (and beauty), not very far from a shamanic scenario, where ontological barriers become chaosmotic thresholds. But this approach also requires a new conceptuality, even if the process is slow and will probably meet much resistance. In this sense, some terms and references in Policardi’s book should be reconsidered and perhaps eliminated altogether, such as the taken-for-granted universal validity of the opposition between ‘nature’ and ‘culture’ (even to highlight the value of the former as ‘transformative exteriority’), the understanding of siddhis as supernatural powers (at least within the context analysed in the book), or the affordance theory of James Gibson as theoretical support to explain the interaction between human and non-human in the Yoginīs. This last point seems to me especially important, since the parameters of the affordance theory presuppose a natural determinism that can only be affirmed if one cancels out the universe as shown by the most singular elements of the Yoginī cults. However, the solution to such problems is also contained in nuce in Policardi’s book. In her ample bibliographical spectrum, she quotes, among many other authors, Tim Ingold, who may well serve as a key to re-read the interaction of the human, the animal and the divine beyond the usual hermeneutical adoption of a ‘natural setting’ from which different (cultural) representations – among which symbols – are built. Tim Ingold questions that assumption from a phenomenological point of view, in a similar way to Philippe Descola’s questioning of it from a rather structuralist optics. For these authors, the rigid scheme of ‘nature’ as given factual setting and ‘culture’ as representational construction built upon it reveals much more the domination of the modern Western lens than any universal intelligibility standard about reality. And it is precisely a consideration of pre-metaphysical, local and tribal cultural complexes (like that analysed by Chiara Policardi) that may contribute to detecting other world-configurations even when they appear already inserted in analogical or metaphysical systems tempting us to think of them as synchronic architectural units. This is no specific ethnographic matter, but an invaluable hermeneutic tool to South Asian Studies in general.

Chiara Policardi’s Divine, Feminine, Animal guides us through the abyssal palimpsest of Yoginī cults with a sense of safety. As Raffaele Torella points out in his foreword, the author sails through the tempests of fragmentariness, irregularity and overflow of material on the textual and iconographic level with remarkable intelligence and self-confidence. I would add the following: she leads us to another shore, the landscape of which is barely visible, since we are still dependent on the lens used to observe and participate in the previous one. I hope she does not abandon us at this stage and pursues her extraordinary research work with the same determination and diligence – as if driven by the śaktipāta of her hybrid deities – to shed more light on this barely explored territory.