Adrián Navigante

DALAIN DANIÉLOU: USER’S GUIDE

Owing to its multifaceted and transversal character, Alain Daniélou’s work seems to call for an interpretation free from canonical standards of knowledge reproduction, as also from any form of dogmatism. However, using some of the author’s heterodox aspects to justify amateurish and superficial opinions turns out to be the opposite of what emanates from his work and heritage. This essay is a tentative response to opposite extremes in the reception of his thought: excessive (and stagnating) philological rigor and vulgar (and parasitic) amateurism.

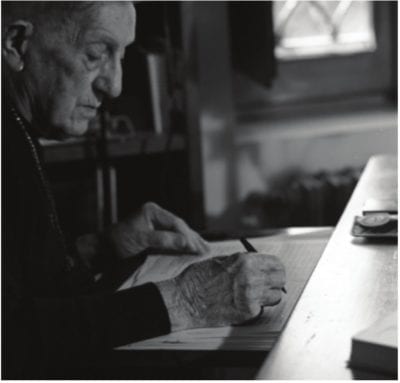

Alain Daniélou at the Labyrinth in 1992, photo by Jacques Cloarec

Alain Daniélou at the Labyrinth in 1992, photo by Jacques CloarecFrom interpretation to use, and back again

In his books Lector in Fabula (1979) and The Limits of Interpretation (1990), Italian semiotician and writer Umberto Eco clarifies the difference between the notions of ‘interpretation’ and ‘use’ of texts. We can talk of ‘interpretation’ when the reader tries to do justice to the intentio operis, whereas the superposition of the intentio lectoris should be defined as ‘use’1. What is the advantage of ‘interpretation’ over simple ‘use’ of a text (and by extension: of any culturally codified product)? An interpretation goes beyond the reader’s tastes and preferences, guides him/her in the process of understanding and prevents his/her reading-process from being fully spontaneous and arbitrary. The interpreter wants to do justice to a source. The user, on the contrary, plays with that source, as if it were both too close to him and too far. He may therefore disregard its authority as a whole, as well as its power to guide – to the point of denying the very concept of ‘source’ and the related question of origins –, transforming the source into a simple pretext. The unprejudiced nature of pretextual readings can result in creative interpretation-games (like the transformation of a Sophoclean tragedy into a universal key to understanding the human psyche) or in presumptuous falsifications (like the transformation of the Vedic tradition into a monotheistic religion of the book), but these two poles hardly ever appear in their pure form. In the same way, the question of limits does not revolve around ‘interpretation’, but rather around the crystal-clear distinction between ‘interpretation’ and ‘use’ – which proves to be utopian if we consider the complex history of effects related to the textual character of myths, gods, liturgies, societies or traditions in general. Umberto Eco makes a point of it: “use and interpretation are certainly two abstract models”2.

Some examples should help illustrate the blurred boundaries between ‘interpretation’ and ‘use’. The monumental project of reconstructing Indo-European language and culture3 could not be called an interpretation in the strict sense of the word, since the cultural (that is, categorial, discursive and pragmatic) ‘source’ happens to be the product of mainly phonological and morphological speculations. The idea is simultaneously to create the cultural texture one is supposed to reconstruct. In spite of its logical procedure4 and pretension of strictly scientific method, the question of origins in this case does not lead back to a terminus ab quo but reveals – or rather produces – a terminus ad quem. As to the ‘use’ of a text, there are of course good and bad instances. Good ones, even in the hands of essay-writers (whose work is detached from criteria of objectivity), have sometimes more cognitive value than the results of exacting interpretations driven by a respectable ‘will to truth’. There is little or no doubt that one can learn much more from Roberto Calasso’s approach to the Torah in his book Il libro di tutti libri (The Book of all Books, 2019) than from some exegetic comments pursuing the intentio operis in a literal – as opposed to a literary – way. At the same time, a regrettable misunderstanding persists with regard to the idea of ‘artistic’ work: the category of art is thought to differ entirely from (epistemic) knowledge in so far as the former is related to pure invention without any regard for facts, whereas the latter concerns facts and rejects any subjective interference. This viewpoint poses many problems. Are the Homeric poems fictionally detached from the historical facts leading to the Trojan war and the consequences of it? One could ask the same about the Mahābhārata and the Kurukṣetra war, or the Rāmāyaṇa and the vicissitudes of the Kośala Kingdom during the reign of Daśaratha. The answer is negative. Homeric poetry is a work of memory making use of history. This use is based on a conception of time and remembrance (mnêmosynê) that is not quite the same as ours. Memory in the Homeric age does not only have a relationship with past events and figures on a horizontal axis. It also implies the presentification of such contents and their rearrangement with a future perspective, as in the art of divination5. This means that any historical ‘interpretation’ of ancient Greece dealing with Homer is based on material emerging from a poetical ‘use’ of history. Something similar can be said of the Indian genre called itihāsa, which is not only what we understand by history, but is embedded in a much broader scope in which a vertical axis (mythic, cosmic, divine) coexists with a re-telling of past events that are difficult to situate between the limits of chronology and a past beyond the past (illud tempus). In the case of itihāsa, the reader can glimpse not only history, but also a stage with human and non-human agents, ranging from canonical gods and their ontological fluctuations (Viṣṇu, Rāma-Kṛṣṇa) to cows and monkeys embodying the whole power of the earth and natural landscapes (Pṛthvī, Hanumān)6. It is there that we find – quite paradoxically – fundamental elements to reconstruct the logic of past events out of a dis-placed source related to poetic remembrance. ‘Interpretation’ is sometimes (re-)born out of ‘use’, which means that ‘use’ is perhaps closer to the source than ‘interpretation’ claims to be – and that the idea of ‘source’ is always tricky.

Alain Daniélou and Shiva: Western interpretation, Hindu use

There are few authors so difficult to classify as Alain Daniélou. This difficulty goes hand in hand with the creation of pre-texts justifying the one or the other approach to his thought. A man without academic credentials, he cultivates a principle of uncertainty with regard to the location of his own ideas: musician, painter, dancer, writer, and translator; Shaivite initiate with a Dionysian bent; libertine homosexual with traditional ideas. If we resort to Umberto Eco’s classification, he was a man of ‘use’ rather than of ‘interpretation’, that is, a playful and even subversive reader. At the same time, he was fully committed to the preservation of traditional cultures and displayed conservative opinions that shocked forward-looking intellectuals of the post-Second-War period. Some quotations may illustrate this point: “Most of the problems of the modern West have been caused by maladjusted members of the petite bourgeoisie who spend their lives daydreaming instead of trying to learn”7. “The Indian system [here: the caste system], like any other, has its faults, but it deserves to be examined in depth instead of being portrayed as an abomination by people who have never been in contact with its happy victims”8. “Egalitarianism leads to bloodshed. All people are supposed to be equal but only according to the model of the average, pseudo-Christian European. No one thinks of being equal to the Pygmies, the Santals of India, or the Amazonian tribes”9.

There is no way of understanding Alain Daniélou without a taste for paradox, but a distinction imposes itself: paradox is not exactly the same as contradiction. In the case of Daniélou, it is part of a perspectivistic way of thinking stemming from his experience in the traditional Hindu setting of the pre-Independence period (in the 1930s and 1940s), when “it was possible to discuss any problem without ideological interference or limited preconceived notions; one could think and try to go to the heart of things according to different value systems, without the prejudices or limitations that are created by set beliefs”10. Paradox, in this sense, does not rule out consistency. Daniélou went through different periods: 1. His childhood in Brittany, where he experienced the sacred in nature and its negation in the institution of the Catholic church11. 2. His travel period, when he freed himself from the constraints of his own milieu12. 3. His Indian period, when he was re-educated in an alien culture to the point of familiarising himself with it13. 4. His last period, when he sought to integrate his Indian experience by relating it not only to pre-Christian cultures in Europe, but also with non-European cultures in other parts of the world (Africa and South America)14. However, there is a binding thread (sūtra) uniting each one of those dissimilar phases: his relationship with nature and his attention for the sacred. This begins in his childhood with his experience of the sacred in the woods; it goes on with his liberation from the Catholic heritage of his family (which fell altogether upon his brother’s shoulders, Cardinal Jean Daniélou); it becomes fully structured with his study of Hindu polytheism and his strong bond with Shiva (who, in the thought of Daniélou, is related not only to Rudra but also to Paśupati)15, and it is consolidated with the re-integration of a forgotten past in the history of mankind, a past in which human and non-humans (gods, animals, plants) were closely related and religion was not reduced merely to the self-proclaimed verticality of the human element (man as ‘crown of creation’). The questions are manifold: how did Daniélou read Shaivism? How did he retell his own life-story in the light of it? How did he expand it to create a new philosophy of life far beyond the Indian context?

To begin with, Daniélou’s Shaivism is not reduced to the solid place scholars assigned it in the almost undefinable religious and cultural complex called ‘Hinduism’. Since it is not scholarly reliable to speak of a Hindu god until his documented appearance, the consolidation of the god Shiva – focusing on textual evidence and maintaining a certain fidelity to the intentio operum16 – presupposes the decline of the Vedic god Rudra and the rise of the trimūrti (Brahmā-Viṣṇu-Śiva). This happens in the epic period (from 200 BCE to 300 CE), paradoxically enough in the context of Vishnuite texts: the role of Shiva (as the great destroyer) in the outcome of the battle that forms the central core of the Mahābhārata equates in a certain scene that of Krishna (the preserver of dharma)17, just as Shiva’s epiphany granted to the sage Upamanyu (in the same epic poem) bears witness to an elevation of that god that seems to go even beyond Krishna18. If one resorts to consolidated theological literature and the archaeological evidence of temples, the Shaivite religion can be said to have been constituted some centuries after the epics, that is towards the year 600 CE19. The Hindu point of view is different, since the transformations of a deity are not viewed as socially conditioned by the dynamics of human groups, but rather as relating to different aspects of the same non-human power. In this sense, the different names of Shiva (Paśupati, Hara, Rudra, Bhairava, Kapālamālin, etc.) are manifestations of his power in different contexts within the same tradition – which is not only horizontal (historically-related), but also vertical (ritually or mythologically codified) and does not depend on human, but on divine will. The reading logic ensuing from this attitude is quite different, since the opera to be dealt with demand transversal and creative (rather than linear and reconstructive) use, and the elements borne in mind are arranged and combined in a different form according to religious symbols (the tiger skin as the embodied power of prakṛti; the spear pāśupata as the symbol of pralaya; a club with a skull at its end [khaṭvāṅga]standing for his power over death [mṛtyum-jaya]), attributes of the god codified in mythology (the three eyes related to sun, moon and fire; the erect phallus standing for the unlimited life-force; the matted hair pointing to the uninterrupted flow of sacrificial offering balancing creation and destruction) and analogical relations with natural forces (Rudra and Paśupati with fire – with its synthesis in ‘fiery-breath’ [āgneya-prāṇa]–, Shiva – as archer [śarva]and all-pervading nourisher or ruler [īśāna]– with earth and wind).

‘Interpretation’ is sometimes (re-)born out of ‘use’, which means that ‘use’ is perhaps closer to the source than ‘interpretation’ claims to be – and that the idea of ‘source’ is always tricky.

Daniélou deals quite extensively with the Hindu reception of Shiva in his monumental book Hindu Polytheism20, where it becomes clear that uses and scholarly interpretations of the ritual, mythological and theological aspects of the god produce two different universes – each with its legitimate aspects. Hindu use of the sacred corpora plays with the whole transversal flow of creative associations, partial analogies, principles of belief and devotional overtones. In such a context, the reader’s fidelity consists in a sort of hermeneutic amplification that, from the point of view of strenuous textual ‘interpretation’, detaches itself from the intentio operum. In other words, Daniélou shows that if one bears in mind the dynamics of oral transmission, the ‘use’ imposes itself on the ‘interpretation’, but the user cannot be defined as possessing a free and playful subjectivity (as one may think from a Western point of view). What appears to be purely subjective is in fact a hidden aspect of the objective structure amplifying itself. In other words: the intentio lectoris is inscribed in a much broader canonical structure that seems to be rigid but is in fact more flexible than the hermeneutic freedom attached to an isolated (reader-)subject.

On use and misuse: the reverse-side of “orthodoxy”

Hindu Polytheism shows the native comprehension of the divine in terms of phenomenal multiplicity: “Existence is multiplicity. That which is not multiple does not exist. We may conceive of an underlying, all-pervading continuum, but it remains shapeless, without quality, impersonal, nonexistent. From the moment we envisage divinity in a personal form, or we attribute to it any quality, that divinity belongs to the multiple, it cannot be one; for there must be an entity embodying the opposite of its quality, a form complementary to its form, other deities”21. Alain Daniélou’s emphasis on polytheism is on the one hand a protest against ethnocentric prejudices22, while on the other it is a critique of the notion of unity applied both to an instance of radical transcendence and to the sphere of world-immanence. In fact, from a Hindu point of view, neither the one nor the other is true: “To speak of a manifest form of a unique God implies a confusion between different orders. God manifest cannot be one, nor can the number one apply to an unmanifest causal aspect. At no stage can unity be taken as the cause of anything, since the existence implies a relation and unity would mean existence without relation”23.

Daniélou’s use of Hinduism presupposes the affirmation of a polytheistic world-view against two tendencies that turned out to be a misuse of Hindu tradition (very often under the aegis of orthodoxy and primordiality): 1. The equation of Hinduism and monotheism, usually related to Vedic literature, carried out in the colonial context mainly for ideological and political purposes. This equation forgets that non-duality is not unity, that the Rigveda is, strictly speaking, quite different from a sacred text like the Torah or the Koran, and that – as Daniélou says – “a simplified system (monism) could never accommodate the multifaceted, complex unity that characterises the Hindu pantheon, where, although every element can, from a certain point of view, be equated with every other, the whole can never be brought back to numerical unity”24. 2. The esoteric invention of a universal Vedānta (a radically monistic metaphysical doctrine), against which Daniélou clearly pronounces himself: “In the general picture of later [i. e. modernized]Hinduism, an exaggerated importance has been attributed to some philosophical schools of monistic Hinduism which developed mainly under the impact of Islamic and Christian influences and which aim at reinterpreting Vedic texts in a new light”25. In spite of the manifold problems that can be found in his writings, René Guénon (who undeniably influenced the young Daniélou) represents the subtlest and most creative version of this simplification – in the face of which the mediocrity of his contemporary acolytes is quite striking. The most vulgar version of this simplification is carried out by contemporary managers of spirituality claiming knowledge of Hinduism out of a concoction of commonplaces varying from decontextualized quotations from the Rigveda and some principal Upaniṣads to a kindergarten interpretation of the Bhagavad Gītā and truncated or indirect quotations of Śaṅkarācārya’s philosophy. This ideological dilatation of Vedānta betrays some central aspects of any hermeneutic operation within the classical Indian context: a sense of perspective, argumentative subtlety and the propaedeutical acceptance of the opposite point of view. Since René Guénon had a talent for invention (the myth of his own initiation into Advaita Vedānta, the doctrinal complex of his Primordial Tradition, his oppositional categories ‘East-West’, etc.), we can say that the exercise of his intentio lectoris deserves the category of ‘use’. All the other attempts mentioned above aimed at reducing the richness of Hinduism to a watered-down carbon copy of monotheistic theology should be regarded as misuses, since the intentio lectoris is in such cases so poor that it cannot renew, reshape or even partially bring to light the aspects of the opera or textual corpora they claim to treat with orthodox fidelity.

As we can see, the main problem is not the difference between ‘interpretation’ and ‘use’, that is, the problem of ‘use’ as conscious transgression of any hermeneutic operation led by a ‘will-to-truth’, but rather the impossibility of contributing – even transgressively and subversively – to a certain history of effects by means of enriching the symbolic pregnancy of the tradition(s) in question. Misuse begins with the denial and even degradation of both opera and intentiones through the dissonant improvisations of an utterly ignorant or dangerously fanatic reader.

The transcultural sphere of ‘use’: Daniélou’s heritage in the XXI century

While Daniélou is an author who, already due to his own way of approaching the traditions he deals with, practically forces his readers to an exercise of (creative) ‘use’ rather than of (rigid) ‘interpretation’, his amplification, based on an elaboration in thought and experience of the different life periods mentioned above – childhood in Brittany, travel, Indian-sojourn, return to Europe – excludes and even forbids misuse. The sense of the sacred arising in his early childhood was reaffirmed first in Benares and then in the context of his researches on archaic pre-Christian religions. His connection with Nature that took place in the first period became, in the last part of his life, the key to his most inspiring thoughts on ‘religion of Nature’ (one of his definitions of Shaivism)26 and the ‘animistic attitude’27 that could save the world from imminent catastrophe. His archaeology of the sacred is approached not only with a sense of rigour, but also with the necessary artistic freedom (mainly gained in his period of travel and profoundly refined during his Indian period28) to let imagination play its part in consolidating received and elaborated ideas into a concrete philosophy of Life. Any (rigid) interpretation of Hinduism would not have allowed him to reflect on the possibility of a ‘Dravidian difference’29, that is, the idea that the type of world-configuration codified in the Shiva cult might have originated before the Vedic period and might have been, as such, the Indian version of a much broader religious substratum extending far beyond the Indian subcontinent.

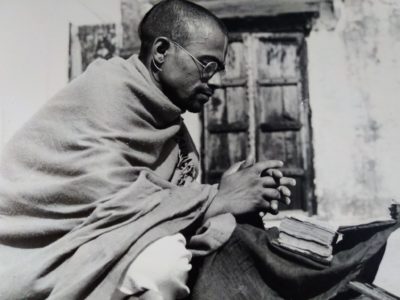

Brahmin reading Vedic hymns, photo by Alain Daniélou

Brahmin reading Vedic hymns, photo by Alain DaniélouSober ‘interpreters’ consider Daniélou’s ‘use’ of Shaivism extending beyond the Indian territory, especially his programmatic amalgamation of it with the Dionysian religion, as an abuse in the field of comparative religion. They also reject the opposition between Aryans and Dravidians in terms of ‘foreign invaders’ and ‘autochthonous groups’ as unacceptable speculation in the light of contemporary archaeological research (which contends the invasion theory as an explanatory key to the Indo-Aryan migration phenomenon)31. Both arguments miss the point of Daniélou’s ‘use’ of Shaivism, since not only its scope but also the consequences of his readings are quite different from what is assumed by his detractors. Daniélou’s interpretation of Shaivism has, of course, its problems, but they are not located where ‘interpreters’ condemn his ‘use’ as a transgression of acceptable intellectual standards32.

On taking a closer look at it, we see that the amalgamation of Shiva and Dionysos is no mere exercise in comparative religion, but a hypothesis based on Daniélou’s experience, as he explicitly declares in his book Shiva and Dionysus. This experience includes four central elements: 1. His own tendency towards a religion of Nature (as opposed to the abstract postulation of a transcendent being as source of all manifested reality). 2. His initiation into Shaivism in the orthodox context of Benares. 3. His research on the transmission of knowledge among the Sadhus of India as well as the difference between this special (ritual, cosmological and doctrinal) knowledge and the institutionalized aspects of Hinduism. 4. His increasing conviction of an archaic religious substratum encompassing pre-Vedic India, sub-Saharan Africa, ancient Europe (Minoan and Thracian culture) and America. What is the relevance of this ‘use’ and how can it become a misuse?

Although comparative tendencies in the study of religions have fallen from favour in the field of specialised research, they can still be an incentive for interdisciplinary attempts to free scholarly thinking from its increasingly monolinguistic straitjacket. Alain Daniélou was a man of his time, but he also had intuitions ahead of his time. He inherited the vocabulary and theoretical framework of a generation of thinkers pursuing the question of origin, identity and primordiality – a question that, for many reasons, is no longer tenable. For a certain time, he remained one-sidedly attached to an Indian metaphysical and cultural framework, thinking that it was a real alternative to Western models (which it is not), and that Western models were empty (which is not always the case). He believed in the purity of traditions, thus disregarding the complex processes leading to the formation of an apparently homogeneous cultural group. Is his extensive (and in many ways culturally transgressive) use of the Shaivite corpus – beyond geographically bounded and theologically well-defined parameters – a good use or a misuse? The amazing fact is that Daniélou permanently surpassed the limits of his own thoughts and convictions. He widened his perspective without incurring in dogmatic abuse; he remained creative without losing his fundamental basis, thus avoiding misuse of sources. In this sense, he was able to reverse not only the commonplace opinion on questions like difference, otherness, man and nature, perception and cognition, religion and life, etc., but even the contextual limitation of his own arguments.

Interpretation begins with ritual performance and displays multiple uses. Kālī sacrifice among peasants in Annapūrṇa, photo by Adrián Navigante

Interpretation begins with ritual performance and displays multiple uses. Kālī sacrifice among peasants in Annapūrṇa, photo by Adrián NaviganteIt is especially in his last writings, notably in Shiva and Dionysus, that one appreciates this reversal of thinking and the role of this reversal for a transcultural debate in this century. Daniélou did not abandon former arguments but reshaped and extended them to extract the core of what he had known as ‘Shaivism’ in India. The book is not about two deities (Shiva and Dionysus), but rather about what these two deities paradigmatically show from other (forgotten or repressed) world-configurations. He coined the compound ‘Shaivite-Dionysian’ to summarise the common features of a world-view that challenges the pitfalls of modern civilisation: the separation of human beings from Nature, the impossibility of access to an invisible world of entities, moral condemnation of erotic and ecstatic rituals, the constitutive role of sacrifice in the dynamics of manifest reality, the view of matter as devoid of spirit and of Nature as the perishable order of being separated from the divine34. The main task of the later Daniélou is not to reach liberation [mokṣa]in radical transcendence [puruṣa, brahman], but to understand, as deeply and realistically as possible, the divine play [līlā], the labyrinth of the universe, the fantasy of the gods in which human beings have to find their own way and make the best of their own lives35.

Alain Daniélou’s emphasis on polytheism is on the one hand a protest against ethnocentric prejudices, while on the other it is a critique of the notion of unity applied both to an instance of radical transcendence and to the sphere of world-immanence.

In his postface to Ailton Krenak’s book Ideias para adiar o fim do mundo (Ideas to Delay the End of the World)36, Eduardo Viveiros de Castro relates the idea of the end of the world in the context of the Anthropocene to the failure of a certain idea of humanity, a humanity focused on a metaphysical depreciation of the world that ignores the fundamental question of relations37. Our ‘humanity’ is ecocidal and ethnocidal, because its own hubris (in the form of an emancipation project) has uprooted and detached it from all other (visible and invisible) living beings. Viveiros de Castro calls this regrettable fact “ontological disjunction”38 and does not limit it to the modern period of Western industrialisation but extends it back to the transcendental breakthrough of the axial period39, a time most humanists were proud of, since it was thought to be the era of the ‘main world-religions’ (Hinduism, Buddhism, Zoroastrism, Judaism, Christianity, Islam). But in the light of the manifold catastrophes nurturing the idea of a final disaster, human beings begin to realise that these cultural achievements were only one side of the coin – and, in fact, the wrong one. Traditions have worked on the past and the future, but now it is all about the present, and the key-issue is space, not time, since our immediate space (the natural environment) is severely endangered. In this sense, the timeline-based struggle between tradition and progress, backward-oriented and forward-looking world-views, has become obsolete. All ideas about development and growth, together with ideas about gods, spirits, and other forms of subtle existence must be redirected to Nature. Shamanism has become the treasure-trove that Hindu soteriology used to be a century ago, since human beings need to learn how to reconnect with the inaccessible parts of Nature, to compensate for the major loss caused by their own God-complex. “Delaying the end of the world”, writes Viveiros de Castro, “means to defer the final battle between […]the ‘humans’ or ‘moderns’ – that is, the arrogant slaves of the empire of transcendence – and the ‘earthlings’ or ‘terrestrials’, that is, the multitude of humans and non-humans whose simple existence is a form of resistance”40. The transcultural challenge of this century is essentially related to this problem, and to the position we take with regard to it.

Daniélou’s position, which emerges from his reading of Shaivism, is quite clear. His pagan-polytheist philosophy of Nature, which some ‘interpreters’ of Hinduism may condemn as misunderstanding or even falsification, is perhaps the best ‘use’ of the Indian heritage one can make in this period, since it stands the test of a time-crisis and a change of epochal axis. It also shows that the least interesting aspect of Indian thought today lies in attachment to simplified models of transcendence (like those portrayed by acolytes of a watered-down Neo-Vedānta) that miserably fail to relate the problem of humanity to the problem of relations, the problem of the sacred to the mystery of (a re-animated) Nature, and the experience of that mystery to a world-vision in opposition to what Western modernity arrogantly thought of as the only valid model for all humans.

- Cf. Umberto Eco, I limiti dell‘interpretazione, Milano 2016 (first edition 1990), p. 49.

- Umberto Eco, Ibidem., p. 55.

- Consider, for example, the following remark by Émile Benveniste: “the notion of ‘Indo-European’ has in the first place a linguistic value, and if we can broaden the scope and reach aspects of culture, it will happen only on the basis of language”, Le vocabulaire des institutions indoeuropéennes, Paris 1969, Vol. I, p. 8.

- Logical procedures can begin with false premises (which in et per se do not at all betray their rational character on a formal level) and reach convincing conclusions, as long as the reader follows the procedure without questioning the slip between premise (and inference) and axiom (and self-evidence).

- Cf. Homer, Iliad I.70, the reference to the diviner Chalcas, “who knew all things that were, those that were to be and those who had been before” (hos hêdê tà t’eónta tà t’esomena pró t’eónta). Marcel Detienne refers to the amplified conception of memory in the context of archaic poetry in comparison with the understanding of it in modern times, cf. Marcel Detienne, Les maîtres de vérité dans la Grèce archaïque, Paris 2006, especially pp. 66-67.

- For the association of Hanumān with yakṣas cf. Philip Lutgendorf, Hanuman, in: Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. I: Regions, Pilgrimage, Deities, Leiden 2009, pp. 579-586)

- Alain Daniélou, The Way to the Labyrinth, New York 1987, p. 316.

- Alain Daniélou, Ibidem, p. 319.

- Alain Daniélou, Ibidem, p. 318.

- Alain Daniélou, Ibidem, p. 308.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Ibidem, pp. 5-6.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Ibidem, Chapter 4: The discovery of the world, pp. 61-85, and also Alain Daniélou, Le tour du monde en 1936, Monaco 2007 (first edition: Paris 1987).

- “For several years, I read nothing but Hindi and Sanskrit, no book, newspaper, or article besides those I had to translate. I found this very difficult at first, but the discipline I imposed on myself allowed me to grow accustomed to another mode of thought, a different conception of life and the world” (Alain Daniélou, The Way to the Labyrinth, p. 135). His learning process did not limit itself to the Shastric tradition, but encompassed a complementary side rejected both by the British administration and by the pseudo-intellectual vulgata of some modern Hindus: “For several years, I was daily in contact with Brahmanand, a very strange and ugly young man who was mostly interested in the magical forms of tantrism. […]Through him I became acquainted with some very arcane details of tantric rites, particularly those relating to the significance of the labyrinth and the predictions that can be read in the bowels of the sacrificial victims” (Alain Daniélou, Ibidem, pp. 135-136).

- The main contribution of Alain Daniélou’s later period is his book Shiva and Dionysus (1979), but the composite construction of the divine power explored in that book as well as the cultural substratum related to it reappear in essays like Relations entre les cultures dravidiennes et négro-africaines (1978, in: Alain Daniélou, La civilization des differences, Paris 2003, pp. 151-165) and Les divinités hallucinogènes (1992, in: Alain Daniélou, Yoga, Kâma: le corps est un temple, Paris 2005, pp. 121-125).

- Alain Daniélou, Shiva et Dionysos, Paris 1979, p. 67 (in connection with the definition of Rudra as lord of animals in Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa XII.7.3.20).

- The plural (opera, genitive plural operum) refers to the textual corpus in which Shiva is alluded to or treated in detail, from Rāmāyāṇa and Mahābhārata to some Mahā-Purāṇas and Tantra-Āgamas.

- Cf. Peter Bisschop, Śiva, in: Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. I, pp. 741-754, especially p. 744.

- Since Upamanyu tells Kṛṣṇa to worship Shiva himself (cf. Mahābhārata. 13.14.48-50).

- Cf. Ysé Tardan-Masquelier, Un millard d’hindous : histoires, croyances, mutations, Paris 2007, p. 140.

- Namely in chapters 15 (Śiva, the Lord of Sleep), 16 (The Forms of Rudra-Śiva) and 17 (The Image of Śiva), cf. Alain Daniélou, Hindu Polytheism, pp. 188-203, 204-212 and 213-221 respectively. Daniélou adds a chapter about the metaphysical aspect of manifestation, in which the relationship between the god Shiva and the conception, symbolic and worship of the liṅga plays a central role (cf. Ibidem, pp.222-231).

- Alain Daniélou, Ibidem, pp. 7-8.

- “In our times monotheism is often considered a higher form of religion than polytheism. […]Monotheism is always linked with a culture, a civilization. It is not through its forms but in spite of them that gifted individuals may reach spiritual attainment. […]Monotheism is the projection of the human individuality into the cosmic sphere, the shaping of ‘god’ to the image of man” (Alain Daniélou, Ibidem, p. 10).

- Alain Daniélou, Ibidem, p. 7.

- Alain Daniéliou, Ibidem, p. 11.

- Alain Daniélou, Ibidem, p. 11.

- Cf. “Shaivism is essentially a religion of Nature”, Alain Daniélou, Shiva et Dionysos, Paris 1979, p. 20.

- Alain Daniélou, Ibidem, p. 34.

- Alain Daniélou always combines the free exercise of artistic expression in the modern sense of the word with disciplined existence in the milieu of traditional arts. The first aspect becomes clear especially in his short-stories (for example the community of friends he depicts in La partie des dès who live quite independently of all conventions, cf. Alain Daniélou, Les bétails des dieux et autres contes gangétiques, Paris 1983, pp. 169-194), the second – which he made much more explicit during his life – in essays like Les arts traditionnels et leur place dans la culture hindoue (in: Approche de l’hindouisme, Paris 2007, pp. 49-90).

- “Some of the most profound aspects of Hindu thought have been linked in the past, as they are still now, with the philosophy of Śaivism. This philosophy, originally distinct from that of the Vedas, belongs to another and earlier stratum of Indian civilization, which was gradually assimilated by the conquering Aryans” (Alain Daniélou, Ibidem, p. 188). “Shaivism, the religion of the ancient Dravidians, was always the religion of the people. Its metaphysical, cosmological and ritual conceptions were preserved by communities of wandering ascetics living on the fringe of the official society, whom the Aryans scornfully called Yatis (wanderers), Vrâtyäs (untouchables) or Âjîvikäs (beggars)” (Alain Daniélou, While the Gods Play, Rochester: Vermont 1987 (first edition in French: La fantaisie des dieux et l’aventure humaine, Monaco 1985), p. 15.

- Which did not stop further attempts in that direction, for example Bernard Sergent’s remarkable book Le dieu fou: essai sur les origines de Śiva et Dionysos, Paris 2016.

- Such counter-arguments are nevertheless not based on substantial evidence, but on a more plausible conceptual framework for current research trends revolving around notions like ‘gradual immigration’ and ‘acculturation’. Interestingly enough, the nationalist agenda in India rejects the invasion theory as ‘Eurocentric’, whereas Daniélou’s affirmation of an indigenous substratum – as opposed to an alien Indo-Aryan element – was part of his anti-ethno-centric reaction- strategy against the Orientalist constructions of primordiality attached to an Indo-European (in the sense of Indo-Aryan) cultural complex.

- In dealing with this problem I leave aside the esoteric critique of Daniélou based on a vulgar appropriation of René Guénon and his idea of Tradition, since it does not deserve even a succinct analysis.

- Basing his speculation on arguments by M. R. Sakhare on a Lemurian origin of the Dravidian people (which would also connect them to Madagascar and Indonesia), Daniélou sees the summit (but not the cradle) of that culture in Mohenjo Daro and Harappa. He also relates the divine pair Enki (Lord of the Earth) and Ninẖursanĝ (Lady of the Sacred Mountain) in the Sumerian pantheon with Paśupati and the Harappan Mother Goddess, thus relating the culture of the Indus Valley to ancient Mesopotamia (cf. Alain Daniélou, While the Gods Play, pp. 6-8). His reflections on Śiva-Paśupati and Murugan, whom Daniélou associates with Zagreus (the Great Hunter) and Dionysos (the God of Nysa), include the possibility of a link between these deities and the sacred images of Lagba Yoruba (cf. Alain Daniélou, Relations entre les cultures dravidiennes et négro-africaines, in: La civilisation des differences, p. 158). Speaking about the pre-Aryan origin of Basques, Sardinians and Berbers, he points to the fact that they share their blood type (type O.) with American Indian groups. The typological language feature of agglutination as well as the religious symbols of these cultures permit him to venture the hypothesis that “they apparently belong to the same human species [as the Dravidians]” (Alain Daniélou, While the Gods Play, p. 9).

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Shiva et Dionysos, especially the preface and the introduction (pp. 11-16), where most of these features are programmatically mentioned anticipating his programme for the future in the last part of the book (The Return of Dionysus, pp. 292-295).

- This is clearly expressed in a lecture dating back to the 1980s held at Aix-en-Provence, in which Daniélou delineates the main aspects of what he called ‘shaivite philosophy’, the main purpose of which is “to understand the nature of the world, the role and the destiny of living beings”. This universe, writes Daniélou, “can be seen as a play, a fantasy stemming from a transcendent being. But this being conceiving the world is necessarily external to it. It precedes the rise of space, time and existence” (Alain Daniélou, Cosmologie shivaïte et polythéisme, in: Shivaïsme et tradition primordiale, Paris 2003, p. 37-42, here p. 37). One can see quite clearly that the use of Shaivism that Daniélou displays distances itself considerably from soteriological systems and focuses on a participation in the mystery of manifest reality – as a sphere of interdependence from which humans cannot detach themselves. This position is also expressed in Daniélou’s opposition between Shaivism and Jainism: “Eversince prehistory, India knew two great religious trends: the first one is Shaivism, a religion of Nature aiming at perceiving the divine in its work and integrating itself into that order; the second one is Jainism, an anthropocentric religion essentially focused on moral and social values” (Alain Daniélou, Le renouveau shivaïte du troisième au dixième siècle, in: Shivaïsme et tradition primordiale, pp. 43-67, here p. 43).

- My quotations stem from the French edition of that book: Ailton Krenak, Idées pour retarder la fin du monde, Paris 2020 (first edition in Portuguese: São Paulo 2019).

- Cf. Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, Le monde a commencé sans l’homme et s’achèvera sans lui, in: Ailton Krenak, Ibidem, p. 55.

- Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, in: Ibidem, p. 58.

- The term ‘axial period‘ (Achsenzeit) was coined by Karl Jaspers in his book Vom Ursprung und Ziel der Geschichte (1949) and was inspired by the epochal observations carried out by Abraham- Hyacinthe Anquetil Duperron (1731-1805) with regard to the relationship between the spiritual situation of Persia at the time of Zarathustra and that of Egypt, Greece, Rome, India, China and Israel. In postulating a holistic movement of humanity towards transcendence that does not reduce to the Christocentric view, Jasper’s reflection attempted to go beyond a monogenetic view of the development of humanity. But at the same time, it proclaimed a universally valid ‘becoming aware (bewusst-werden)’ of humanity after a specific codification of experience occurring in the dominant cultures to which such an awareness- process of the totality of being was ascribed (basically the cultures mentioned by Anquetil Duperron, obviously reshaped after the Orientalist propensity of the post-Second-World-War period).

- Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, in: Ibidem, p. 59.