Anand Mishra

VEDIC SCIENCES AND OUR CHANGING PERSPECTIVE TOWARDS THE VEDAS

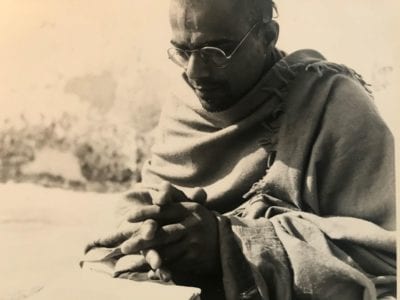

Brahmin reading an ancient text on the terrace of Rewa Kothi in Benares. Photo by Alain Daniélou

Brahmin reading an ancient text on the terrace of Rewa Kothi in Benares. Photo by Alain DaniélouIn the Brahmanic tradition, Vaidika Vijñāna (knowledge of the Veda) has been exercised to preserve the wisdom contained in the Vedic corpus. The modern interpretation of it by Indian scholars has transformed this concept into a “Vedic science” aimed at reading the whole development of Western modern science into the Vedic corpus. Anand Mishra traces this transformation back to Svāmī Dayānanda Sarasvatī and the roots of Hindu Nationalism and shows the pitfalls of that enterprise through Svāmī Karpātrī’s critique of Dayānanda Sarasvatī. The essay poses the question of tradition, its preservation and the conflict-laden dynamics of change and legitimation also in dealing with modern culture and the universalist project of Western science.

This essay is an English version of a talk given by the author in Hindi in the “Lecture series on Vedic Science“ (Veda-vijñāna-vyākhyānamāla) organised by Sampurnanand Sanskrit University, Varanasi on 24th December 2020.

Vaidika-vijñāna and ‘Vedic science’

Vaidika-vijñāna — the term used for Vedic Sciences – would normally mean knowledge (jñāna) or special understanding of the content of the Vedas and the Vedic literature. By the term Veda, one understands primarily the four collections — Ṛgveda, Sāmaveda, Yajurveda and Atharvaveda. Vedic literature primarily consists of the texts belonging to the six ancillary disciplines associated with the Vedas, namely — Śikṣā (phonetics), Chandas (prosody), Nirukta (etymology), Vyākaraṇa (grammar), Kalpa (instructions on ritual practices) and Jyotiṣa (astronomy). It also includes such branches of knowledge as Āyurveda (medicine), Dhanurveda (archery), etc. One can say that a large part of Indian scholarly effort, since several centuries before the Common Era, has been a continuous and continuing effort to understand the knowledge and wisdom contained in the Vedic literature. These efforts are also generally directed towards preserving their content. Thus, the great grammarian Patañjali (II century BCE) instructs “Grammar should be studied for the purpose of preserving the Vedas.”1

Feelings of responsibility towards preserving the meaning of the Vedas, and anxiety that they might become meaningless and purposeless are so strong that Śabarasvāmin (III century CE) is even ready to turn down the injunctions of the tradition! At the very beginning of his commentary on the Mīmāṃsā-sūtras of Jaimini (III century BCE), he reacts to the charge put forward by his opponent that:

“They (i.e. the elders) recite the following — ‘after having learned the proper recitation of the Veda, the student should take the bath’2. Here, a student taking a bath and at the same time desiring to know the Dharma (and hence prolonging his status as a celibate) would override the above injunction (to take a bath, marry and enter into the next stage of life). And one must not override an injunction.”3

To this objection by his opponent that on the basis of the above injunction one should rather finish study of the Vedas, which consists of their proper recitation only, and immediately enter into the next stage of life as a householder – leaving aside the desire to know the meaning and the purpose of the Vedas, the answer of the Ācārya Śabarasvāmin is clear:

“We will override this injunction! If we do not override this injunction, then we will be rendering the meaningful and purposeful Veda meaningless and purposeless.”4

One can therefore consider Vaidika-vijñāna to be the knowledge or sciences developed to preserve the Vedas, such as the six ancillary disciplines of phonetics, prosody, etymology, grammar, ritual sciences and astronomy, as also to ascertain the meaning and purpose of the Vedas such as the Mīmāṃsā, or the science of interpretation, etc.

Vaidika-vijāna or ‘Vedic Sciences’ is, however, a phrase used nowadays to convey very different ideas. According to intellectuals who use this phrase frequently, it is meant to express the following aspects:

1. The principles and knowledge of modern science are also present in the Vedas, though in a coded and cryptic manner. Contemporary scientists and Veda-scholars (especially from India) should make concerted efforts to recognise, decipher and discover modern scientific knowledge in the Vedic literature.

2. Since the Vedas are an infinite source of knowledge, therefore, the discoveries and truths thus far undiscovered by modern scientists can also be distilled from the Vedic corpus.

3. One reason for this is also that in comparison with the modern sciences, the vision of the Vedas is more comprehensive. Here, not only the physical world, but also the realm of consciousness as well as the spiritual world are taken care of.

Svāmī Dayānanda Sarasvatī, founder of the reformist movement Ārya Samāja. Source: Wikimedia commons

Svāmī Dayānanda Sarasvatī, founder of the reformist movement Ārya Samāja. Source: Wikimedia commonsThe above way of looking the Vedas as the repository of modern scientific knowledge is followed by several prime institutions of learning in India. Thus, the Banaras Hindu University has recently established a major Centre for Vedic Science (Vaidika Vijñāna Kendra). The School of Sanskrit and Indic Studies at the Jawahar Lal University, New Delhi, has organised several conferences and talks on this subject. Prof. Girish Nath Jha and other scholars of the same institution have also brought out an edited volume titled Veda As Global Heritage. Scientific Perspectives, recording the proceedings of the International Veda Conference held there in 2016.5

Instead of multiplying the number of examples, it would be pertinent to take a brief look at a few examples by some of the most influential and prominent exponents of this approach. Foremost among them is Prof. Subhash Kak, who teaches Computer Science at the Oklahoma State University, USA. In his book The Astronomical Code of the Ṛgveda, Subhash Kak attempts to show that the organisation of the hymns of the Ṛgveda within the divisions Sūkta and Maṇḍala, etc. is based on the secrets of astronomy6. The way these hymns are collected and organised tells us about the truths of astronomy, e.g. the course of the planets or distances of the Sun or Moon from the Earth, etc. The seers who saw the Mantras or the Ācāryas who collected them in this manner were aware of these secrets. There are many such scientific facts and truths encoded in the Vedas that can be discovered by realising the essence of Vedic thinking. Similarly, Dr. Raja Ram Mohan Roy (not to be confused with the famous thinker of the XIX century) who holds a Ph.D. in Materials Science and Engineering from The Ohio State University, USA, enounces similar ideas of recognising the truths of Particle Physics in the Ṛgveda in his book Vedic Physics: Scientific Origin of Hinduism7.

Authors like Subhash Kak and Raja Ram Mohan Roy present the view that according to the Vedas, the inner world of consciousness and spirituality is connected with the outer physical and material world. He affirms that the inner sight, full of consciousness and spirituality, can discover the truths of the outer world and material sciences in a much more comprehensive manner than the methods of modern sciences. This point of view is also put forward forcefully by Dr. David Frawley, also known as Paṇḍita Vāmadeva Śāstrī, the founder of the American Institute of Vedic Studies in the USA.

Criticism of Vedic science

There has been widespread criticism of the ideas and propositions put forward by writers such as Subhash Kak et alii. Several reputed indologists have pointed out the indiscrepancies and lack of acceptable sources, as well as methodological shortcomings in their writings. For example, the renowned indologist Dr. M. A. Mehandale from the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Pune, questions the basis of the calculations produced by Subhash Kak in his book The Astronomical Code of the Ṛgveda by pointing out that the present arrangement of the hymns of the Ṛgveda cannot be the same as in the original collection, which follows the principle of arranging the hymns in descending number of stanzas8. But strong opposition to the approach of Subhash Kak et alii is formulated by Meera Nanda in her several publications, especially in her book Prophets facing Backward: Postmodern Critiques of Science and Hindu Nationalism in India.9 In this book she contends that the movement for Vedic Sciences is not just ignorance and apathy regarding scientific enquiry, but is rather an active instrument to establish the ideology of Hindutva in India. This ideology supports the inhuman and divisive caste-based social system and promotes faith in unscientific ancient Indian knowledge systems and it stifles the establishment of an egalitarian, humanistic order based on rational and scientific thinking. In her opinion, this ideology gets its intellectual nourishment from the writings of Neo-Hinduism thinkers like Svāmī Vivekānanda and Sri Aurobindo on the one hand, who promoted and supported the idea that ancient Indian thought is also relevant for modern times, and on the other hand intellectual movements sprouting under the umbrella of postmodernism over the last few decades. Meera Nanda is opposed, not only to the ideas and approaches of Vedic Sciences, but even more so to those supporting post-modern intellectual theories and programmes that promote local, traditional and even non-scientific approaches. In her opinion, thinkers like Thomas Kuhn with his theory of paradigm shifts in the history of science, or Paul Feyerabend professing epistemological anarchism have provided a sort of ‘epistemic charity’ on the basis of which such mindless ideas as Vedic Sciences may end up propagating ideological trends like that of Hindutva.

Svāmī Dayānanda Sarasvatī’s approach towards the Vedas and Svāmī Karapātrī’s refutation

The inclination to see the Veda as the repository of the discoveries of modern science and technology is not limited solely to some contemporary individuals like Subhash Kak or Raja Ram Mohan Roy, who live in the USA or Canada but have their roots in India and work mostly in areas of modern science. Svāmī Dayānanda Sarasvatī (1824-1883), the founder of Ārya-Samaj, started interpreting the Vedas in this manner. Dayānanda’s perspective regarding the Vedas becomes clear in reading his important work Ṛgvedādi-Bhāṣya-Bhūmikā (ṚgBh) or Introduction to the Commentary on Ṛgveda etc.10 According to the editorial foreword of the revised edition, this text was composed by Dayānanda in the years 1876-1878, and its first part was first published in the year 1877 by the Lazarus Press in Varanasi. Dayānanda wrote this introduction before composing his commentary Satyārtha-Prakāśa on the Vedas in order to provide the necessary information about his view of the purposes of writing a new commentary. This introduction by Dayānanda is therefore an important document on his standpoint regarding the Vedas, put forward in his own words.

In the section regarding the subject matter dealt with in the Vedas, Dayānanda states:

“Now the deliberation on the subject matter of the Veda. In this context, there are four subject matters dealt with in the Veda — on the basis of the four parts, namely vijñāna (science, scientific usage), karma (rituals for the welfare of everyone), upāsanā (worship) and jñāna (knowledge). Among these, the first one, i.e. the subject matter of vijñāna (science, scientific usage) is the primary. As it relates to the direct understanding of all the objects beginning from the highest lord down to the smallest blade of grass.”11

According to the revised Hindi translation explaining the above passage by Paṇḍita Yudhiṣṭhira Mīmāṃsaka:

“ ‘Vijñāna’ means knowing the real meaning or purpose of all the objects. ‘Vijñāna’ is said to be that which facilitates appropriate application of the three, i.e. karma, upāsanā and jñāna, and the direct understanding of all the objects beginning from the highest lord down to the smallest blade of grass, to use them in an appropriate manner. Therefore, this subject matter is the principal among these four.”12

One can consider Vaidika-vijñāna to be the knowledge or sciences developed to preserve the Vedas, such as the six ancillary disciplines of phonetics, prosody, etymology, grammar, ritual sciences and astronomy.

In the same book, Dayānanda attempts to show the roots of the knowledge about the telephone, telegraph (“Tāravidyāyā mūlam” p. 234-236), ships and aeroplanes, etc. (“Nau vimānādi-vidyā-viṣayaḥ” p. 223-233). Thus, Dayānanda attempts to show the ‘true meaning’ or satyārtha of the Vedas. He interprets the utterances of the Veda in accordance with the discoveries and theories of modern sciences (of his time), considering the Vedas to be their source and regarding them to enjoin their application in this manner.

He explains the second subject matter of the Veda, namely its application or karma, also in a particular way. He writes:

“Of that (i.e. karma) as well, there are two types — one is for the attainment of the highest human goal, namely which unfolds to facilitate only liberation by the knowledge of praising the lord, prayer, worship, following the (divine) commands and the performance of rightful duties. The other is that which combines material possession and desire with rightful duties for the fulfilment of worldly affairs.”13

It is important to note that Dayānanda professes to perform the traditional śrauta rituals and sacrifices like agnihotra and aśvamedha in a modified manner with different material offerings and sets down different kinds of results accruing from their performance.

“In all the (śrauta) rituals beginning with agnihotra up to the aśvamedha, offerings of properly prepared and refined materials with qualities of fragrance, sweetness, nourishment and remedial for diseases are offered in the fire, for the sake of purifying the air and rain-water, and through this ritual the entire world gets happiness. And what is enjoined for eating, housing, travel, arts, handicrafts, technologies and for the purpose of establishing social order, from this mainly personal happiness results.”14

In short, according to Dayānanda, Śrauta or Vedic rituals and common righteous worldly efforts are on par, both bringing happiness. The difference between common worldly activities and Vedic rituals is that, while the former are capable of bringing happiness primarily to one who undertakes them, the latter, especially offerings of four types of material, namely fragrant, sweet, nourishing and remedial herbs, bring happiness to all by purifying the air, rain-water and the environment.

This brief exposition of the ideas put forward by Dayānanda regarding science in the Vedas and the nature of Vedic rituals makes it clear that publications by authors such as Subhash Kak on Vedic Sciences and many conferences and talks in educational institutions in India nowadays follow this view of Dayānanda. This is equally true for many talks of the type ‘The effect of Vedic rituals on our environment’, etc.

In a way, the process of rendering the Vedas scientific is also the process that renders them materialistic. The strong opposition by traditional Vedic scholars which Dayānanda faced during his lifetime is well known. Even afterwards the debate continued between traditional Vedic scholars following the Sanātana-paramparā and scholars following the Ārya-Samāj. One of the questions of this heated debate was whether modern science is in the Vedas or not. Paṇḍita Yudhiṣṭhira Mīmāṃsaka, a versatile scholar of grammar and Mīmāṃsā and follower of Svāmī Dayānanda, writes on page 77 of the first volume of his book Mīmāṃsā-Śābara-Bhāṣyam:

“From 12th till 18th November 1964 an ‘Assembly of (scholars from) all the branches of the Vedas’ was organised in Amritsar by Svāmī Karapātrī Jī, which was presided over by Svāmī Nirañjana Tīrtha Jī, the Ācārya of Śāṅkara-pīṭha of Puri. During that occasion on 16th, 17th and 18th November a scholarly discussion took place on two matters Is there science in the Vedas or not? and Are the Brāhmaṇa texts to be called Vedas or not? Regarding these questions, the scholars and seers following sanātana-dharma took the position that ‘There is no science in the Vedas and Brāhmaṇa texts are also called Vedas’. Contrary to this, my stance was that ‘the Vedas propound primarily science, and only Mantra-Saṃhitā are Vedas, not the Brāhmaṇa texts’.”15

I have been unable to obtain more literature on the above-mentioned scholarly debate as yet, but the writings of Svāmī Karapātrī are easily available. Here the voluminous Sanskrit text Vedārtha-Pārijātaḥ (VePā.) is of special significance.16 Disgruntled by the interpretation of the Vedas, mainly by Svāmī Dayānanda, and perhaps inspired by earlier efforts of scholars like Bhaṭṭa Kumārila (7th cent. CE) who mentions in the beginning of his famous work — Ślokavārttika –, “Mīmāṃsā has been predominantly considered as a materialistic point of view in our own times. This effort of mine is to bring it back to the āstika path”.17

Svāmī Karapātrī composed this voluminous text primarily to refute Dayānanda’s position on the Vedas. At the very beginning of this text, he mentions the purpose of writing it:

“After a long time passed by (once the attempts to malign the Vedas were thwarted by earlier Mīmāṃsā scholars such as Bhaṭṭa Kumārila, etc.) a person called Dayānanda spoiled the traditional system completely. Following the path of materialistic philosophy, but to show it as the āstika path, he indiscriminately collected contentless matters from here and there, and created a book, not very small but also not very profuse, and called it a ‘commentary’ (on the Veda), aiming at fame, acclaim and following for himself, while deluding the world.”18

Svāmī Karapātrī undertook a thorough and extensive refutation of Dayānanda in over 1500 pages, showing that each and every sentence of Dayānanda’s Ṛgvedādi-Bhāṣya-Bhūmikā was full with errors and contrary to tradition. He points out the different spheres of the Vedas and of modern scientific enquiry:

“Modern scholars accept science as a method involving proper observation of objects, their classification and systematization based on logical reasoning, and then testing it through experiments … Not a single postulation of scientific truth of this kind is seen in the Ṛgveda, neither have you shown that any of the Mantras set forth this kind of explanation.”19

Svāmī Karpātrī, founder of the religious and cultural movement Dharma Sangh, in the 1940s. Photo: Alain Daniélou Foundation Archive, Zagarolo

Svāmī Karpātrī, founder of the religious and cultural movement Dharma Sangh, in the 1940s. Photo: Alain Daniélou Foundation Archive, ZagaroloHe ridicules and rejects the ideas of Vedic rituals serving humanity by bettering the environment, etc.:

“Moreover, your statement that — ‘the steam which is produced during Vedic rituals, purifies the air and water and brings the whole world happiness’ — what is the source of this statement? Is it known through the statements of the Vedas or is it some human logic: which is its source? If it is based on reasoning, then it does not originate from the Vedas. If it is known through the Vedas, then the corresponding Vedic utterances should be presented. How is it possible that burning a limited amount of ghee, saffron, etc., in the ritual fire would take away the unlimited amount of stench of excreta, urine, skin, marrow, flesh, bones, etc.? Moreover, earth, water, fire, etc. take away that stench by their own nature, and if this is possible through these elements in this natural manner, then what is the reason for burning jaggery, ghee, milk, grains and herbs in the fire? The kind of cleanliness which is seen in places maintained by modern scientific systems without the help of Vedic rituals, that kind of cleanliness is not seen even in the homes of Agnihotrins.”20

Moreover, he questions, refutes and discards the fundamental hermeneutical techniques used by Dayānanda to interpret the Vedas in this wrongful manner. According to him, this would lead to a complete abnegation of the traditional system of interpretation of the Vedas:

“In Mīmāṃsā a two-fold division of the ritual actions is made in terms of subsidiary (guṇa) and primary (pradhāna). According to the manner suggested by you, all Vedic actions have to be considered as subsidiary, on the basis of their being performed for the sake of others. Therefore, the statements that teach about the primary actions would be rendered useless, as primary actions would not follow from them.”21

He points out the insufficiency of Dayānanda’s propositions:

“Dayānanda provides the description of knowledge about ships and aeroplanes in Ṛgveda 1.116 by wrongly interpreting these verses as he likes. This is also useless, since he does not describe the method of building these ships and aeroplanes.”22

The brief sketch outlined above shows beyond doubt that the contemporary approach of searching for or stating knowledge of modern sciences in the Vedas is not the traditional Indian way of looking at the Vedas, but started with thinkers like Dayānanda Sarasvatī about a century ago. This is evident by looking, on the one hand, at the works of traditional scholars on this subject, such as Śabarasvāmin (III century CE), Bhaṭṭa Kumārila (VII century CE), Sāyaṇācārya (XIV century CE), where no such enquiry is present, and on the other hand, reading Dayānanda’s works such as the Ṛgvedādi-Bhāṣya-Bhūmikā in which there is special emphasis of the Vedas having primarily scientific content, and finally by studying the Vedārtha-Pārijātaḥ by Svāmī Karapātrī, which refutes and rejects the propositions of Ṛgvedādi-Bhāṣya-Bhūmikā and seeks to restore the traditional view that there is no science in the Vedas.

The process of scientification of the Vedas is also the process that renders them materialistic. The strong opposition by traditional Vedic scholars which Dayānanda faced during his lifetime is well known.

Even if one is ready to accept that, since modern sciences have developed in the last few centuries, and since traditional scholars like Śabarasvāmin and Bhaṭṭa Kumārila are prior to these developments, the absence of such enquiries is therefore appropriate in their texts and the enquiries and approaches of scholars like Dayānanda should not be discarded, just because they are contemporary and modern; still certain problems remain.

The foremost concern, for traditional thinkers like Svāmī Karapātrī is that, if one accepts the Vedas as the source of modern sciences, then the traditional theoretical system put in place to safeguard the Vedas would fall asunder. The facts, ideas, and theories of modern sciences keep changing and advancing continuously. This is accepted by every scientist. Considering the Vedas as a collection of scientific ideas that are continuously varying, and sometimes wrong, mostly in need of improvement, would be a heavy burden on the traditional principle of considering the Vedas as the ultimate source of valid cognition.

A further concern is that of degrading the Vedas as advocating materialistic points of view. Scientific truths are based on direct perception (pratyakṣa) and inference (anumāna). The essential nature of the Vedas is that they inform us about that which only the Vedas can tell. The Vedas are the source of injunctions that originate from them in the first place, and do not provide re-renderings of scientific truths.

Even if one sets aside the above concerns worrying traditional scholars like Svāmī Karapātrī and is ready to see the Vedas as the endless source of all knowledge, including scientific knowledge, an immense problem still remains. What would then be the method of discovering these scientific truths already enshrined in the Vedas? Since the corpus of the Vedas is limited, discovery of scientific facts and principles is consequently only possible once the manner of ascertaining them is made clear. As yet, there is no evidence of arriving at scientific truths by analysing the Vedas with the help of the traditional methods of Mīmāṃsā, etc. And, in any case, if the application of Mīmāṃsā, etc. systems of knowledge to the Vedas should start delivering modern scientific discoveries, then apart from the happiness of being successful in this, one would also feel disappointed that scholars who developed and applied these systems of knowledge, beginning from Jaimini and even earlier up to Svāmī Karapātrī at present, had not discovered these truths! Dayānanda and others seem to be reading their desired sense out of the sentences of the Vedas by supplying special etymologies and associating the ideas in Vedic statements with scientific knowledge. Writers like Subhash Kak also speak of yogic visions, on the basis of which one can decipher the scientific knowledge encoded in the Vedas. It is known that sometimes intuitions lead to a significant leap in the world of science as well, and scientific method alone is not sufficient for the scientific quest. Accepting even the application of yogic vision to discover scientific truths, the question arises: would one then still need the Vedas or would the yogic vision suffice?

These and similar such traditional and logical questions creep up, once the position that the Vedas are the source of modern scientific knowledge is taken seriously. Looking at the widespread following of this point of view among the Indian academic world, as also public opinion nowadays, makes thinkers like Svāmī Karapātrī who fostered the culture of reflection and discussion on matters of importance for Indian tradition all the more relevant.

- Rakṣārthaṃ vedānāmadhyeyaṃ vyākaraṇam. (Mahābhāṣya-Paspaśāhnika 17). Joshi, S. D. (ed.): Vyākaraṇa-Mahābhāṣya, Paspaśāhnika, Poona 1986, p. 6.

- By learning is meant here proper recitation of the Veda by exactly following the recitation of the teacher (gurumukhoccāraṇānuccāraṇa). Taking the bath (snāna) is the final convocational ceremony when the student finishes his study of the Veda. He can now leave the house of the teacher and from his current first stage of life, namely brahmacarya or celibate student, can now enter into the second stage of life as a householder or gṛhastha.

- Evaṃ hi samāmananti — vedam adhītya snāyāt — iti. Iha ca vedam adhītya snāsyan dharmaṃ jijñāsamāna imam āmnāyam atikrāmet. Na ca āmnāyo nāma atikramitavyaḥ. Paṇḍita Yudhiṣṭhira Mīmāṃsaka: Mīmāṃsā-Śābara-Bhāṣyam — Ārṣamata-vimarśinyā Hindī-vyākhyayā sahitam (Prathamo Bhāgaḥ), Bahalgarh 1977, p. 6.

- Atikramiṣyāma imam āmnāyam. Anatikrāmanto vedam arthavantaṃ santam anarthakam avakalpayema. (Ibidem p. 6).

- Girish Nath Jha et alii: Veda As Global Heritage — Scientific Perspectives, Delhi 2019.

- Subhash Kak: The astronomical code of the Ṛgveda, New Delhi 2000.

- Raja Ram Mohan Roy: Vedic Physics: Scientific Origin of Hinduism, Ontario 2015.

- M. A. Mehandale: Review of the Astronomical Code of the Ṛgveda by Subhash Kak, In: Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 1996, Vol. 77, No. ¼, pp. 323-325, here p. 324.

- Meera Nanda: Prophets facing Backward: Postmodern Critiques of Science and Hindu Nationalism in India, New Brunswick 2003.

- Paṇḍita Yudhiṣṭhira Mīmāṃsaka (ed.) : Ṛgvedādi-Bhāṣya-Bhūmikā — Śrīmaddayānanda-sarasvatī-svāminā nirmitā saṃskṛtāryabhāṣābhyāṃ samanvitā, Sonipat (Hariyana) 2015.

- Atha veda-viṣaya-vicāraḥ. Atra catvāro veda-viṣayāḥ santi, vijñāna-karma-upāsanā-jñāna-kāṇḍa-bhedāt. Tatra ādimo vijñāna-viṣayo hi sarvebhyo mukhyo’sti. Tasya parameśvarād ārabhya tṛṇa-paryanta-padārtheṣu sākṣād bodhānvayatvāt. (ṚgBh p. 49).

- „विज्ञान“ अर्थात् सब पदार् थों को यथा र्थ जानना।… „विज्ञान“ उसको कहते हैं कि जो कर्म उपासना और ज्ञान इन तीनों से यथाव त् उपयोग का करना। इससे यह विषय इन चारों में प्रधान है। (ऋग्वे दादि -भाष्य -भूमि का पृष्ठ ५०)

- Tasyāpi khalu dvau bhedau mukhyau staḥ — ekaḥ parama-puruṣārtha-siddhyartho’rthād ya īśvara-stuti-prārthanopāsanājñāpālana-dharmānuṣṭhāna-jñānena mokṣameva sādhayituṃ pravarttate. Aparo loka-vyavahāra-siddhaye yo dharmeṇārthakāmau nirvarttayituṃ saṃyojyate. (ṚgBh p. 56).

- Sa ca agnihotram ārabhya aśvamedha-paryanteṣu yajñeṣu sugandhiḥ miṣṭa-puṣṭa-roga-nāśaka-guṇair yuktasya samyak saṃskāreṇa śodhitasya dravyasya vāyu-vṛṣṭijala-śuddhikaraṇārtham agnau homaḥ kriyate, sa tad dvāra sarva-jagat sukhakāry eva bhavati. Yaṃ ca bhojanācchādana-yāna-kalā-kauśala-yantra-sāmājika-niyama-prayojana-siddhyarthaṃ vidhatte so’dhikatayā svasukhāyaiva bhavati. (ṚgBh p. 56).

- नवम्ब र सन् १९६४ की १२ से १८ तिथि यों में अमृतसर नगर में स्वाम ी करपात्री जी के तत्त्वाव धान, और पुरी के शांकर पीठ के आचार्य स्वाम ी नि रञ्जन देव जी के सभापति त्व में सर्वव ेदशाखा-सम्मे लन का आयोजन हुआ था । उसमें ता॰ १६-१७-१८ तक ‘वेद में विज्ञान है वा नहीं’ तथा ‘ब्रा ह्मणग्रन्थ ों की वेदसंज्ञा है वा नहीं’, इन दो विषयों पर शास्त्रचर्चा हुई थी। इसमें सनातनधर्माव लम्बी विद्वा नों और महात्मा ओं का पक्ष था — “वेद में विज्ञान नहीं, और ब्रा ह्मणग्रन्थ ों की भी वेदसंज्ञा है।” इसके विरोध में मेरा पक्ष था — “वेद में विज्ञान का ही प्रा धान्ये न प्रति पादन है, और मन्त्र संहि ताओं की ही वेदसंज्ञा है, ब्रा ह्मणग्रन्थ ों की वेदसंज्ञा नहीं है।” Paṇḍita Yudhiṣṭhira Mīmāṃsaka: Mīmāṃsā-Śābara-Bhāṣyam — Ārṣamata-vimarśinyā Hindī-vyākhyayā sahitam (Prathamo Bhāgaḥ), Bahalgarh 1977, p. 77.

- Anantaśrī Karapātrī Svāmī: Vedārtha-Pārijātaḥ, (in two volumes), Vedaśāstra Research Centre, Kedarghat, Varanasi, 1979 (vol.1), 1980 (vol.2).

- Prāyeṇaiva hi Mīmāṃsā loke lokāyatīkṛtā, Tām āstika-pathe kartum ayaṃ yatnaḥ kṛto mayā. (Ślokavārttika 10). S. K. Ramanatha Sastri (ed.): Ślokavārttikavyākhyā Tātparyaṭīkā, Madras 1971, p. 3.

- Gate bahutithe kāle dayānandābhido janaḥ

Dūṣayāmāsa sarvā tāṃ paddhatir yā sanātanī.

Lokāyatika-mārgastha āstikyam iva darśayan

Khyāti-sammāna-pūjārthaṃ loka-vañcana-hetave,

Itastatas samānīya sārahīnam udakṣaram

Prāduścakre bhāṣyanāmnā na laghīyo na vistṛtam.(VePā. 16-18). - Ādhunikās tu pratyakṣeṇa padārthān anubhūya tarkeṇa vyavasthāpya prayogeṇa parīkṣaṇam eva vijñānaṃ manyante. … Na caitādṛśam ekam api vijñānam ṛgvede pratipāditaṃ dṛśyate, na tvayā kaścid api mantras tādṛśa vyākhyānopeto darśitaḥ. (VePā. p. 541).

- Kiñca, yaduktam — “yajñādyo vāṣpo jāyate sa vāyuṃ jalaṃ ca nirdoṣaṃ kṛtvā sarvajagate sukhāya bhavati” iti, tadapi kiṃ mūlakam? veda-vacana-gamyaṃ tarka-gamyaṃ vā? tarka-gamyatve tasyāvaidikatvam eva. Veda-gamyatve vacanam upasthyatām. Kathaṃ sīmita-ghṛta-kastūrikādi-homena aparimita-mala-mūtra-carma-majjā-māṃsāsthyādi- daurgandhyāpasāraṇaṃ sambhavati? Pṛthivī-jalāgnyādibhir api svabhāvād eva tad daurgandhyam apākriyate, tadā tair eva tat sambhavet, kim antar gaḍunā ghṛta-dugdhānna-auṣadhādi-prajvālanena? Ādhunika-vaijñānika-vyavasthāyāṃ tu homādim antarāpi yathā śuddhir dṛśyate, tathā agnihotriṇām api gṛheṣu naiva dṛśyate. (VePā. p. 563).

- Mīmāṃsāyāṃ guṇa-pradhāna-bhedena karma-vibhāgā uktāḥ. Tvad ukta rītyā sarveṣam eva vaidika-karmaṇāṃ parārthatvena guṇa-karmatvam eva syāt. Atas teṣāṃ pradhāna-karmatvānupapattyā tadbhodhaka-sūtrāṇāṃ vaiyarthyam eva syāt. (VePā. p. 565).

- Ṛgveda 1.116 — eṣā mantrāṇām āpāta-ramaṇīyam arthābhāsa vidhāya nauvimāna-vidyā-varṇana kṛta dayānandena, tad apy akiñcitkaram, nirmāṇa-vidher avarṇanāt. (VePā. p. 1408).