Amanda Viana

THE IDEA OF A RELIGION OF LIFE IN NON-CHRISTIAN TRADITIONS

In this essay, Amanda Viana examines the validity of the innovative Western philosophical trend called ‘Religion of Life’. Although ‘Religion of Life’ postulates universal validity prior to any cultural determination, the essay shows, through a consideration of Hindu Tantra and Amerindian Shamanism, the inherent difficulties of such a position, since universalism is taken as coinciding with the affirmation of a general validity of Western parameters. Since Religion of Life rests on a speculative mystic conception stemming from Meister Eckhart, Amanda Viana asks whether a discourse (however performative) about Life itself can be up to the aspiration of totality it displays without considering differences inherent to the sphere of what is deemed ‘pure experience’.

Radical Phenomenology of Life

Michel Henry (1922-2002), founder of the philosophical trend known as ‘Phenomenology of Life’, has radicalized a tendency going back to German philosopher Edmund Husserl (1859-1938), bracketing together whatever makes up so-called ‘natural attitudes to the world’ – i.e., the biases and assumptions we automatically apply in dealing with conditions in the world – in order to experience things as they are.

Whereas Husserl’s method took a step back from the constituted doxa of the world and analyzed phenomena in their own intrinsic modality of ‘appearance’1 (by means of which any notion of essence behind phenomena appears as an inessential addition), Michel Henry’s radicalization consists in taking a step back from everything that Husserl built with his science of Phenomenology. Henry’s main purpose was not to lay bare the primordial flow of (intentional) consciousness between the intuition of the ego and the constitution of the object – which for Husserl precedes both the empirical ego and the object in the world –, but to retrace the steps behind intentionality (as primal flow of consciousness) and object-constitution (as articulation and logic of this flow) back to the source of every disclosure of being, which is nothing but Life.

If ‘Life’ is the ultimate source of both the subjective and objective field of experience and knowledge, it becomes irrefutable evidence, and its autonomous manifestation is called ‘self-experience’ [épreuve de soi]. But this primal evidence cannot disclose itself to a ‘science’ (as in the case of Husserl). Where it discloses itself, there is actually no difference between content and method. In fact, Henry distinguishes two modalities of appearing: world-disclosure and life-manifestation2. The world does not express the totality of things, but only their manifestation as objects separated from a consciousness (or indirectly related to it)3. World appearance is always in a modality of exteriority, not because things are outside in the world, but because world-appearance is – if we take it as a manifestation – self-exteriority4. As opposed to it, the manifestation of Life can (phenomenologically) be called ‘self-interiority’, since it is – according to Henry – first and foremost an instance of self-related donation, that is, related to itself before any ‘otherness’ becomes present. This primordial field of Life manifestation (even before we can speak of ‘world’) is for Henry a self-experiencing revelation prior to any other disclosure of individuated beings (as or in the world)5.

In delimiting himself from the classical phenomenology stemming from Husserl, whose method concerns world disclosure out of the transcendentally reconstructed ‘intentionality of consciousness’6, Henry resorts to a logos that goes beyond every articulated flow of finite beings, which he relates to ‘Life’ in the absolute sense of this word. This logos finds itself eminently in Christianity, a religion that – in Henry’s conception – points to the radical phenomenological meaning of Life7 and sets in motion a new paradigm in Western tradition.

According to Henry, until the rise of Phenomenology of Life, Christianity had never been considered in its deepest meaning – hence all the misunderstandings by dogmatic acolytes as well as ruthless critics (like Marx, Nietzsche and Freud). For Henry, the Christian logos points to a self-manifestation of (absolute) Life endowed with relational proto-intelligibility. This intelligibility (prior to any cognitive scheme) is expressed in the relationship between Father and Son. The term ‘God’ (and hence also ‘Father’) is for Henry a religiously encoded way of addressing ‘absolute Life’. Within the relational structure of Life’s self-manifestation, the Father is the unborn and perpetually generating instance. The Son is called the ‘First Living’ – a first passive ‘I’, or more precisely a ‘me’8 – because he receives his life directly from the Father and acts in full identity with Him. The Son translates a primal affectivity as a paradox of radical passivity (or, using Henry’s term: passibility) and full power9. The idea is that Jesus Christ is not an ordinary individual subject to space, time and relativity, but an individuated revelation of Life before the self-externalization of the latter in world-finitude. In other words: Jesus Christ is, for Henry, the Absolute fully encompassed in individuated flesh. The reference to the Gospel of John (1, 14) is clear and explicit: the logos became flesh, that is, God as Life affected Himself as the First Born – which means that the self-affection of Life is uninterrupted, an eternal flow in which there is no separation between Father and Son. The Son is in this sense no abstraction, but the singular self in which God experiences and generates himself10, and ultimately there is no separation between the Son and any other human being, since the revelation of the Logos as a ‘coming of Life into flesh’ means that in the deepest dimension of my own self-affection (that is, an affection related to my living body and hence not coming from the outside) I am (like) the Son. For Henry, individuation may exist as a third person11, but individuation in a radical sense (which Henry calls ‘ipseity’) lives only in the first person and under the declension of Life (that is, as me and not as I).

The manifestation of Life can phenomenologically be called ‘self-interiority’.

On the basis of the ideas expounded above, human beings can orientate their life-experience according to the world or according to absolute12 Life. If the orientation is towards the world, the modality of appearing will be that of self-exteriority, meaning that the individual will sever him/herself from the affectivity of Life and become trapped in the realm of objectified things. For Henry, a human being is really alive only when he is in Life, which means when he (re-)discovers within himself the self-experience of the Life-pathos as self-manifestation of the Absolute. The experience of Life-pathos is by no means a mere figure of thought. Rather, it has to do with impressions, emotions, feelings, acts of will and other types of tangible life-manifestations in our most concrete inwardness, which Henry calls our ‘inner body’. The ‘inner body’, meaning everything that is me with regard of my innermost life-affections, is the threshold to the ‘flesh’; this, in turn, is the Absolute or the Father – before everything – begetting me in homologation with the First Living, who is the Son13.

Michel Henry’s philosophy is without doubt an attempt to create an access to Life. Since no modality of appearance implying self-exteriority can ever trace the way back to the deepest Life source, the method – beginning with the intentionality of an ego-based consciousness flow (codified in Husserl’s philosophy) – proves incapable of creating this access. Michel Henry seeks the immediate experience of a pre-intentional and pre-conscious Life albeit still logos-related, that is, articulate and consistent14.

Life as the core of religious experience: Towards a Religion of Life

Rolf Kühn is seen as the most radical follower of Michel Henry, especially in the German context. He translated and edited much of Michel Henry’s works and also wrote many articles and books on the question of Phenomenology of Life. In his books, Rolf Kühn equates Life with God and shows the same conviction as Henry: the evidence for God’s revelation finds itself in living beings15. In other words: the self-experience of absolute Life appears in Rolf Kühn – as it does in Michel Henry – as the ultimate ground of its immanent affection, and living individuation is a proof of that event, independently of any metaphysical argument about God. The innovative aspect of Kühn’s thought lies in the concept of Religion of Life [Lebensreligion]. With this concept he attempts to show that any religious experience is grounded in Life, so that Life becomes the only valid universal instance in considering religious experience in any cultural context16.

From the standpoint of Kühn’s Religion of Life, absolute Life imposes itself as proto-religion [Urreligion], since it describes a self-relationality, whose dynamics proves to be ultimately incommensurable with the state of affairs in the world17. At the same time, Life realizes itself in each pathic singular (i.e. living and individuated) self as an expression of simultaneous self-suffering and self-enjoyment. It is precisely in this inner pathic expression of Life – far before any belief or even transcendent instance – that lie the roots of religious experience18. In other words: every living being has a priori a religious life, because it is intrinsically re-linked to the primal source of Life itself19.

A human being is really alive only when he (re-)discovers within himself the self-experience of the Life-pathos as self-manifestation of the Absolute.

According to Rolf Kühn, all religions bear witness to the universal truth of the self-revelation of Life, as long as they express themselves from the source of Life and not from the logic of the world20. However, institutionalized religions can only indirectly be related to absolute Life, since self-experience of the latter takes place exclusively in the inner affective chamber of each living individual – rather than in institutional mediation, liturgy or dogmatic teachings. Stricto sensu, religious experience can be neither objectified nor mediated, but merely inwardly experienced through the only certainty an individual can have – the certainty of something affecting him/her deeply from within, with no gap needing to be bridged over, which takes place even before any idea, representation or concept arises out of this immanent affection. This certainty can be affirmed as long as the individual separates it from any instance of world-openness, since it takes place before the world configurates itself. In this sense, the certainty coincides with the affection, in the same way in which the affection (of the lived body) cannot be distinguished from self-affection i.e. self-manifestation of Life.

The question that imposes itself at this point is whether the certainty of the self-affection of Life can be valid for any religion. But this question cannot be answered if one remains in the immanence of Western tradition without looking beyond its two main expressions: Christianity and Enlightenment. We shall therefore consider three traditions with conspicuously different world-configurations in order to test the validity of the universal ambition of Rolf Kühn’s Religion of Life: 1. Intellectual mysticism in Christianity as conceived by Meister Eckhart. 2. Tantric tradition in Hinduism, and 3. Amerindian shamanism in the Amazonian forest. Out of these elements, we shall try to analyze and put to the test the following aspects of the conceptual framework of Religion of Life: 1. The difference between ‘Life’ and ‘world’. 2. The modality of appearance – or self-manifestation – of Life. 3. The self-affection of Life as the core of religious experience.

The Meister Eckhart portal of Predigerkirche in Erfurt. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The Meister Eckhart portal of Predigerkirche in Erfurt. Source: Wikimedia Commons.Intellectual mysticism: Meister Eckhart’s Christian path

Rolf Kühn’s Religion of Life explicitly resorts to the thought of Meister Eckhart, especially to his idea of the inner structure of the immanence of Life, meaning the effective reality of God, and to his conviction that the unity of the human soul with God can only take place if the individual renounces the world21. One could say that Meister Eckhart’s intellectual mysticism clearly corresponds to Religion of Life, since the deepest connection with God belongs to the inner experience of Life. Eckhart speaks of Life as inner movement, which can be seen in the autonomous character of life realization in each living being, but the radical interpretation of Life in the thought of Meister Eckhart equates Life (as God) with pure intellectuality22. In addition to this, Life (in the absolute sense of the word) appears as a self-sufficient act with inherent determination, an act corresponding to the self-reflection of the divine intellect23. It is precisely this aspect that can justify the definition of Life as proto-religion (in the sense of Rolf Kühn), with the difference that Meister Eckhart speaks the language of Christian theology and translates thus the metaphysical and ontological question of the primal revelation of Life in terms of the relational intricacy of God the Father and his Son. Meister Eckhart’s formula reads as follows: since Life (or pure intellect) is divine and human beings are rational living beings, human beings must know God24.

Meister Eckhart explains that knowledge of God is rooted in the relationship between the Father and the Son. The Father points to the eternal birth-act of absolute Life, while the Son is generated by the Father25 and essentially one with Him26. Since the generative act of the Father is – the Father being pure intellect – also the act of knowing the Son, the first born is no static object of knowledge, but rather a (self-)reflective realization of the generative movement of the Father. In other words: the Son is not separated from the Father; He is the very act of self-reflective knowledge of God. We could therefore say that for Meister Eckhart the human soul can only know God by becoming his Son27, which means that this soul must die to the world and return to eternal Life28. This presupposes full detachment, since the acts of the soul, being impregnated by faculties related to body, temporality and multiplicity, belong to the world and cannot possibly bring about a return to eternal Life. Apart from this, the soul possesses a theoretical power of abstraction that characterizes the ‘intellectual faculty’ of human beings in the world. This turns out to be an obstacle to knowledge of God, which can never be an act of abstraction, since it is a return to the most concrete source of Life. Indeed, God reaches the human soul when the human being attains total passivity towards Him29. He reaches the human soul by generating His Son in it, which means that the soul of the individual is reconfigured as the self-reflective realization of divine knowledge. In this way, the human soul participates in the self-knowledge of God, which at the same time is self-experience, perpetually and singularly generated.

With regard to the Religion of Life, four aspects in Meister Eckhart’s conception are essential: 1. Life is acosmic, invisible and divine. 2. The world is identified with exteriority (the faculties of the soul as ens creatum), while Life is associated with interiority (where the essence of the soul is actualized). 3. Identification of Life with the soul indicates that the soul is a priori rooted in absolute Life. 4. The unity of the human soul with God produces itself in Life, independently of the world30. This means that a living being cannot relate himself to God by means of any form of objectification, but only by reaching the core of (absolute) Life. The essence of religion does not depend on any cultural instance of creation or institution that guarantees it, but from Life in its primal modality of self-revelation31.

Both in Michel Henry as in Rolf Kühn, knowledge of God is essentially related to immanent self-experience of Life (as simultaneous self-suffering and self-enjoyment), which can only take place in a singular (that is, living, human and individuated) self32. For Meister Eckhart, the birth of the soul in eternal Life means the intellectual openness and spiritual disposition of the individual to receive the divine act in him/herself. The individual can experience life in its religious core only if he/she reaches union with God, meaning that he/she participates in the passive character of self-experience of Life – which is the highest act towards the divine33. The consequence of this conception is that Life should be lived in a state of releasement [Gelassenheit]. The junction between the intellectual mysticism of Meister Eckhart and the project of a Religion of Life lies in the role of (absolute) Life as the core of religious experience and the rootedness of the human soul in God by means of identifying God with ‘Life’ – in the absolute sense of the term.

The Tantric tradition

Can we say that religious experience in the Hindu Tantric context also pleads for world renouncement and an inward re-connection of human beings with Life? If so, this tradition could be integrated without much problem within the ‘universal’ scope of Religion of Life, but the first step is to consider how Tantra relates to Life at large and what the consequences of that configuration of experience are. Needless to say, any evaluation of Tantra as a religion of Life implies methodological decisions that are not so simple. A mere consideration of some essential aspects of this religious and cultural complex calls for speculative reduction, and this already becomes a problem concerning the reception of such trends inside and outside the Indian subcontinent. Speculative reduction has usually been made to privilege aspects of a scholastic Tantric heritage that can be related to Western religious soteriology without much difficulty34. The Tantric tradition comprises a multiplicity of different trends, the most conspicuous of which are considered rather heterodox in their orientation – especially if one takes Brahmanic conventions as the Hindu mainstream35. It stems from the cultural context of mediaeval South Asia and is originally related to clans (kulas)36, where the worship of Śakti – or Life-Energy on a rather differentiated cosmic scale – under different (Goddess) forms and names occupies a central place37, since it is the power of the Goddess that creates, preserves and destroys what we call manifested reality38.

If we consider certain features belonging to the rise and early phase of mediaeval Tantra, such as the cult of the Yoginīs and their bond with nature, the practice of blood sacrifice and the manipulation and consumption of impure substances (like menstrual blood, male and female sexual discharges, as well as meat and wine), it is not unreasonable to relate the Śākta-Tantric tradition to tribal cults and indigenous practices in the Indian subcontinent39. Indeed, the figure of the Yoginīs leaves no doubt as to their local and tribal provenance – quite distant from the divine pantheon of Brahmanic kingdoms. Many features confirm this heterodox provenance: their female character (as opposed to the patriarchal tendency of Brahmanism), their therianthropic features (as opposed to the radical separation of human and animal in Brahmanic religion) and their genealogical affinity with non-human beings essentially related to the powers of Nature, such as the personified arboreal spirits [yakṣinīs]and the ambivalent female deities called ‘mothers’ [mātṛs]40, whose powers [siddhis] can be transferred to the Tantric adept if the latter is capable, that is, ritually initiated to deal with them.

For the Tantric tradition Life is – considered in its phenomenological roots – no metaphysical abstraction, but a very concrete energy identified with the Goddess.

With the Kaula movement, especially within the line inaugurated by the mythic figure of Matsyendranāth, the Yoginīs become the focus of teachings, and even leaving aside some extreme practices like cremation ground liturgy and blood sacrifice or replacing them with erotic and yoga-related practices, the unconventional character of those teachings does not disappear, since bodily fluids – especially sexual ones – remain a central feature. Within the ritual framework, however, such power substances [kula-dravyam, lit: ‘clan fluid’]are consumed by the adepts and turned into a sacrament. Although it is true that the character of the sexual transaction in Tantric initiation shows a male dominance (the yoginī of the Tantric vīra is analogically homologated to the Yoginīs as power-spirits, but in concreto she remains a consort [dutī]), the clan fluid – as the centre of Life-power – is of a yonic character41, and the fluid character of the Goddess in the Shakta tradition is a clear sign that ‘indigenous elements’ in Tantra are closely related to the complex yoni-śakti – this complex being a problem for the mainstream discourse of priestly dominance. The impurity of the substances is ritually turned into its opposite when the adept manages to harness it, and Tantric ability and expertise will revolve around that ritual ability – coupled with intellectual domestication. If we consider the speculative development of Tantra, this inversion will be taken to the point where the fluid is homologated as divine consciousness, as the scholastic – and clearly patriarchal – systematization of Tantra later declares42. The so-called ‘right-hand path’ is a fully sublimated and interiorized transformation of all ‘antinomic’ practices, in which everything is metaphysically codified, conventionally accepted and metaphorized to the point of isolating (transcendent) meaning from concrete (immanent) procedures43.

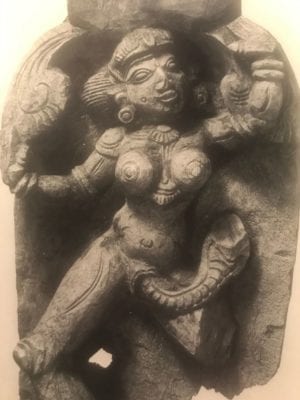

Yoginī with a serpent (Kuṇḍalinī) coming out of her vulva. South India around 1850. Source: Philip Rawson, Tantra. Le culte indien de l’extase, p. 66.

Yoginī with a serpent (Kuṇḍalinī) coming out of her vulva. South India around 1850. Source: Philip Rawson, Tantra. Le culte indien de l’extase, p. 66.In view of all these elements, we may ask how the world and Life are understood in the Tantric tradition, and for this purpose we need to take the manifold trends in the Indian context as a continuum (in spite of radical changes and the possibility of seeing opposing poles). In the first place, the world is understood in an ambivalent manner. It is simultaneously the expression of limitation in which human beings can be trapped44 and a field of (supernatural) powers that can be harnessed and used to the benefit of the adept. Life is – considered in its phenomenological roots – no metaphysical abstraction, but a very concrete energy identified with the Goddess, an energy whose perpetual actualization relinks or synthetizes the micro- and macro-cosmos. The evidence of this lies in Tantric practice, which presents a radical affirmation of a life principle becoming tangible in the manipulation of fluids (and later on in their symbolic offshoots, such as sacred sounds and images)45. Such life-substances can be easily homologated with instances of self-experience of Life in the inner space of the adept’s body, especially if one extends the notion of ‘energy’ [śakti]beyond material fluids and includes every form of emotional investment46, considering what psychoanalysis calls ‘cathexis’ as a sort of ‘mental fluid’. In this sense, we could say that the Tantric tradition attempts to go beyond the life-experience of the individuated human being and consequently to render the inner space of this individuated life-experience receptive to the irruption of the Goddess47 – the term “Goddess” being eventually susceptible to translation as “absolute life”.

In the Tantric tradition, the (self-)experience of ‘Life’ is not only rendered by the term śakti. Kāma too – in the sense of ‘cosmogonic desire’ – is an important notion, also conveying the ambivalence of the Goddess, since the energy of Her desire is always overflowing, creative and destructive, and its beneficial or detrimental declensions depend on the way in which the individual relates to it. Eros is never an obstacle however. It is rather the awakening of divine energy in the limited space of human individuality and also the possibility of attaining a kind of integration of opposites associated with ‘self-realization’48. From this point of view, there is no condemnation of sexual passions, but a tendency to take the reverse-side of its ego-centred manifestations (usually condemned by other spiritual trends) as a door to the concrete experience of divine Life.

For the Tantric tradition, the self-experience of Life manifests itself in the śakti-kāma complex and its relational (and ritually codified) concretion in the interiority of the human adept. This affirmation of an absolute power of Life in the most concrete bodily processes and emotional affections has always a correspondence in the world – so long as the world appears as the ‘articulated power (of the Goddess)’, rather than as a field of external objects. The same tendency that dissolves the separation of pure and impure in the ritual context accounts for the overcoming of the separation between inner and outer. The ontological limits of humans with regard to other beings are in this context of processual and dynamic forces no longer valid49. The Tantric tradition can be seen as a radical affirmation of Life, in which self-experience of it is characterized by unparalleled intensity and even excess – which reveals the self-relational character of Life experience in the inner space of the Goddess’s (energy) body.

Amazonian Shamanism

Can Religion of Life as expounded by Rolf Kühn encompass such a heterogeneous phenomenon as Amazonian shamanism? Is it plausible to think of shamanism from the perspective of Life-rootedness as expounded in the first part of this essay? In order to examine this, we need to put aside prejudices and false definitions concerning the complex phenomenon of shamanism. Shamanism is neither a mystic nor an esoteric trend, but rather a kind of knowledge based on a socially valid consensus with Nature50. It is also an ambivalent practice with specific techniques, which can lead to curing illnesses (in the case of so-called medicine men) or to causing them (defined as ‘shamanic witchcraft’)51. Most important of all: Amazonian shamanism is not based on any metaphysical postulate on Life, but rather on a modality of being in the world, in which the source of life, Nature, is experienced through all living beings (humans and non-humans) by means of established relations. In this sense, human experience – as life experience – has no privilege over other species, since non-humans possess not only the quality of living beings, but also a form of subjectivity equivalent to that of humans. This characteristic is conceptually explained by French anthropologist Philippe Descola: while Western ontology (that is, world-configuration) declares a unity of physicality and a difference of interiority between humans and non-humans, Amazonian shamanism (which he defines as ‘animistic’) conceives a continuity of interiority and a discontinuity in physicality. This means that for the autochthonous folks of the Amazonian basin (where shamanism is a central phenomenon), humans and non-humans have an equivalent mental complexity and rich subjectivity, and the differences lie in the bodily configuration of their souls52.

Shaman Roger López at the Ani Nii Shobo Center in Peru. Photo by José Fuentes

Shaman Roger López at the Ani Nii Shobo Center in Peru. Photo by José FuentesPhilippe Descola claims that in Amerindian myths and also in everyday life, non-humans produce culture – because essentially they are also souled subjects. This means that, in the world-configuration of Amazonian shamanism, what we call ‘nature’ – as being external to the life of the spirit – does not exist. It is neither a fact of experience nor something that can be related to the world in which autochthonous people live, since in this world (fully articulated as it is), the fact of Life and the subjective powers of Nature are intrinsically related and therefore impossible to separate from each other53. Out of this world-configuration, a perspectivistic way of living arises. Neither non-humans nor humans can be substantially determined as such: firstly, because their subjective character reconfigures them on the same level of interaction; secondly, because both of them see themselves – and other beings – from their own perspective; thirdly, because each one of them articulates an intentional point, which varies within the milieu they belong to and according to a basic modality of predator-prey relationship54. By way of example: humans see pigs as prey and jaguars as predators. Pigs (within their own ‘cultural perspective’) see humans as predators, while jaguars (who also have subjectivity) see humans as prey55. It has to be noticed that subjective-character is not the mere fact of having a perspective, but rather the ability to let a world arise out of that perspective. Within the world-configuration of Amazonian shamanism, pigs and jaguars have souls and their activities are impregnated by the activity of the soul (they hunt, they perform rituals, they communicate with other spirits, etc.). This is no mere belief, but the consequence of concrete interaction with them on different levels – where the dominance strategies created by modern Western civilization are absent.

At this point we can summarize the world-configuration of Amazonic shamanism as follows: 1. Humans and non-humans create culture. 2. Their worlds are different because of their difference in physicality (for example, the world of jaguars is not the world of humans). 3. The plurality of worlds is interconnected. 4. The limits between one world and another are fluid, since their perspectives encroach56. 5. Perspectives are no mere ‘representation’ of a world: they create other subjects57. 6. Humans and non-humans are constitutively subject to the perspective of the others, but they can change their own perspective – by means of physical transformation58. This last aspect, of which shamanic knowledge is the anthropological evidence, deserves further analysis on the basis of shamanic ritual abilities and their socio-cultural significance.

In Shamanism, human experience – as life experience – has no privilege over other species, since non-humans possess not only the quality of living beings, but also a form of subjectivity equivalent to that of humans.

Amazonian shamans are ritual specialists. They enter into specific relations with the field of the non-human for cultic, medical or social reasons (we can think of witchcraft, healing ceremonies and hunting). They have the ability of ritually changing their physicality and adopting that of non-humans in order to know their intentions, which shows the bodily concreteness of the notion of a ‘souled subjectivity’ in the context of Amazonian animism. From a perspectivistic point of view, shamans go beyond their own world(-perspective) and penetrate into the world of others to manipulate the relationship between humans and non-humans belonging to those worlds59. This procedure, which is the core of shamanic practice, has nothing to do with renouncing the world in order to return or being reborn to Life – as Phenomenology and Religion of Life preach. The self-experience of Life lies in the core of Nature (as a non-objectifiable field of human and non-human agency) and is not linked to a universal singularity – a soul equated with God before any world constitution –, but of a collective and non-anthropocentric dynamic of forces configurating a plurality of worlds. One could say that Shamans experience – through their own ontological transformation – the pathic self-experience of Life in the modality of self-ness and other-ness at the same time, but in that otherness there is not only the non-human but also the alien world.

Both humans and non-humans participate in the same way in Life, and their worlds are not separated from the instance of Life-revelation seen as the source of those relationships. Indeed, they are so amalgamated with it that the idea of ‘source’ and ‘derivates’ does not exist. At the same time, these worlds are fluid – like the body of the agents acting in them. As opposed to Rolf Kühn’s Religion of Life, here there is no question of re-connection with Life and there is no choice between Life and world(s), since they are essentially interrelated.

For Amazonian shamanism, Life is based on an idea of Physicality that does not have ontological limitations. Physicality is no fixed material quantity, but a moving and changing sheath concealing the subjectivity of the individual60. How can a conception like that of Religion of Life grasp such a register of experiences? What would it mean, for Religion of Life, that the self-experience of Life encompasses animal and human transformations – or immanent Life-declensions – without any ontological limits and distinctions? Without any doubt, Amerindian shamanism presents a religious experience of Life in which other subjectivities come to the fore61, since all kinds of natural beings are integrated in Life dynamics in the same way – for which reason we may speak of a collective self-experience of Life.

Religion of Life: A Naturalist Standpoint?

We have put the main thesis of Religion of Life to the test, that is, the phenomenological thesis of a self-affection of (absolute) Life as core of religious experience, by observing how it works when other modalities of being-in-the-world like that of the modern Western world-configuration (from which Religion of Life stems) are taken into account. According to this thesis, the subjective proto-relationality of Life opens in each singular ‘self’ an immanent – or pre-worldly – religious experience. This means that each individual, taken in the radical sense of living being, is considered to be bound to ‘absolute Life’ (or God) before any cultural difference in modes of behaviour or attitude to the world. Even if some readers may be seduced by the affirmation of a ‘universal rootedness of human individuality in God’ (especially when this root coincides with the dominant religion of the West: Christianity), it becomes difficult to support this affirmation in the light of the data furnished by anthropology of non-European cultures in the last decade of the XX and the first decade of the XXI century.

The so-called ‘ontological turn’ in anthropology has shown that there is no single ontology (as Western philosophy thought: one specific science of being founding the whole building of world-culture), but a system of plural ontologies, and that ontology is not so useful a concept if one avails oneself of it as a ‘science of being’, although on the contrary it can become functional if seen in the sense of a ‘mode of configuring the world’. Philippe Descola has developed a model of four ontologies which goes precisely in the sense of a refined cultural relativism (which dogmatic thinking viscerally rejects): animism, naturalism, totemism and analogism. Such concepts point to a specific way of dealing with continuities and discontinuities, that is, with a basic mode of behaviour founding a world. While naturalism (which is the modern Western Weltanschauung) objectifies nature, homologizes physicality (human bodies are ‘nature’ in the same way as animal bodies) and distinguishes the interiority of humans from the rest of creation, animism inverts such relations so that animals, plants and even invisible beings appear as ‘subjectivities’ and discontinuity concerns the physical sheath of such beings. But there is more to ontological pluralism: the totemic world-view (which can be traced back to the indigenous people of the Australian mainland) is capable of creating identities between certain humans and certain non-humans according to attributes or special characteristics shared by these beings (irrespective of the species to which they belong), while analogism (quite dominant in ancient India and China as well as in the Western middle-ages) establishes relations out of a double scheme of discontinuity, that of dissimilar physicality and interiority. The way in which religious experience articulates itself cannot be separated from the specific features of such differences, since they are not merely conceptual. They try to do justice to different ways of living, and each way re-actualizes Life (even on the level of its phenomenological root) according to the filter of experience shaped by the concrete interaction of living beings.

For the purpose of this essay, our interest lies mainly in the opposition between ‘naturalism’ and ‘animism’. Religion of Life clearly belongs to a naturalist world-configuration, since nature (and per extensionem the world as ‘eccentric instance’) is objectified and turned into a field of living beings without subjective interiority – so that the most relevant question is that of humans and their relationship with God (as core of Life). Since the intellectual mysticism of Meister Eckhart has essentially inspired Religion of Life, we can say that it shares most of the features of the very world-configuration that put an end to the immanent field of Life forces and the horizontal relationship between humans and non-humans. For Meister Eckhart, there is a hierarchy of beings, and even if his thought is inscribed in an analogical conception (where there is sympathy for all things in the cosmos), his radical theocentric standpoint focuses on the birth of the human soul independent of any modality of being in the world.

This is not the case in the Tantric tradition, let alone in Amerindian shamanism. Without over-generalizing and overlooking conspicuous differences, both conceptions – especially if we bear in mind early Tantra62 – make fluid the limitations between humans and non-humans. Nature is no biological fact separated from the human (and divine) spirit. Non-human agency possesses subjectivity and does not act mechanically but intentionally – which is one of the reasons for the complex ritual scaffolding creating in Tantric settings: humans have to know and adapt themselves to the intentionality of non-humans (some of which are at the same time animal and divine, like the Yoginīs). Amerindian shamanism, in which a clearly horizontal type of animism is displayed, does not lack complex ritual techniques, and the power of animal (and plant) spirits plays a similar role to that of divine or semi-divine manifestations of the feminine in early Hindu Tantra.

Naturalism translates the modern Western world-project: Nature is external, an object to be exploited by the spiritual domination of human beings. This domination is most visible in the scientific-technical utopia – clearly expressed by August Comte – that Europeans embarked on to replace the role of God in creation, that is, the idea of ‘progress’. But it is also present in every cultural manifestation – hence the justification of colonialism as a superior point of view of a culture with regard to others (presumably closer to ‘nature’ and therefore ‘primitivism’)63. Christianity is a clear antecedent of this domination project, since it is a religion claiming to hold a universal truth (as opposed to the relative or inexistent validity of all other religions) and wanting to propagate this truth in spite of cultural barriers and different collectively constituted modalities of being in the world. The universal truth (from which Phenomenology of Life extracts its concept of Life) is identified with the Spirit, while inferior forms of religion are associated with ‘nature’ as something that cannot elevate itself to the rang of the Spirit. In this sense, we can say that Religion of Life, the way it is conceived and presented by Rolf Kühn, is an expression of the naturalistic world-configuration – and as such, is in no way universal. Or more precisely: its universality is no phenomenological fact, but a dogmatic affirmation64.

If there is indeed a transcendent common ground of different religious experiences, this ground should be expounded on the level of its specific contextual concretion instead of affirming its a priori validity out of a specific world-configuration (as Religion of Life does out of Christianity). Conceiving self-affection as the intrinsic expression of Life in its own dynamic illimitation (instead of regarding it as an external affection of the empirical individual) is something that should not necessarily be abandoned altogether. The consideration of a plural ontological model could enrich the scope of Phenomenology of Life, since the latter aims, among other things, at gaining access to the deepest layers of human experience – and within this scope the relationship with non-humans is a significant piece of the puzzle. If philosophers of Life manage to replace the dualism ‘life vs. world’ and work on the complexities of each world-configuration as an ‘attitude to Life’, an integration of Nature and Life – towards an enriched notion of Life-World65 as living tissue of relations – could eventually take place.

- It should be borne in mind that in the philosophical school of Phenomenology, ‘appearance’ is not opposed to ‘essence’ (as the field of appearances is opposed to that of ideas in Plato’s philosophy) but is the very name for the manifestation of something even before this ‘something’ can be identified as such with an object.

- Michel Henry: Phénoménologie de la vie. I – De la Phénoménologie. Paris 2003, p. 166

- Cf. Michel Henry: C’est moi la vérité. Pour une philosophie du christianisme, Paris 1996, pp. 23-24.

- Cf. Michel Henry: Ibidem, p. 25.

- Cf. Michel Henry: Phénoménologie de la vie. IV – Sur L’Éthique et la Religion. Paris 2004, p. 100, and also Michel Henry: Können des Lebens. Schlüssel zur radikalen Phänomenologie. Translated with an introduction by Rolf Kühn. Freiburg 2017, p. 40.

- Cf. Michel Henry: Können des Lebens, p.138.

- Cf. Michel Henry: Paroles du Christ, Paris 2002, p. 101.

- With the use of the oblique case (in saying ‘me‘ instead of ‘I’) Michel Henry points to the fact that the roots of the individual lie not in the ego, but in the passive reception of the primal self-affection in which we are perpetually born and kept alive. Cf. Michel Henry: Paroles du Christ, p. 171.

- Cf. Michel Henry: Können des Lebens, p. 71.

- Cf. Michel Henry: Paroles du Christ, p. 114.

- Exist would mean in this case ‘being in the world’, that is, for Henry, in the modality of exteriority with regard to oneself.

- This is nothing else than discovering that also each one of us is the miracle of the incarnation.

- Cf. Michel Henry: Paroles du Christ, p. 124.

- Cf. Michel Henry: Können des Lebens, p. 44.

- See, in this respect, Rolf Kühn: Geburt in Gott. Religion, Metaphysik, Mystik und Phänomenologie. Freiburg: München 2003, pp. 35–36

- Cf. Adrián Navigante. „Das Problem der Selbst-Affektion in nicht-christlichen Religionen am Beispiel des Hinduismus“. In: Jahrbuch für Religionsphilosophie (Band = 16). Edited by Markus Enders und Holger Zaborowski. Freiburg: München 2017, pp. 86–122, especially p. 87.

- Cf. Rolf Kühn: Geburt in Gott, p. 9.

- Cf. Rolf Kühn: Ibidem, 2003, p. 12, and also Adrián Navigante, „Das Problem der Selbst-Affektion in nicht-christlichen Religionen am Beispiel des Hinduismus“, in: Jahrbuch für Religionsphilosophie (Band = 16), p. 92.

- Cf. Adrián Navigante: Ibidem, p. 90.

- Cf. Rolf Kühn: Geburt in Gott, p. 212.

- Cf. Michel Henry: Radikale Religionsphänomenologie. Beiträge 1943-2001, edited by Rolf Kühn and Markus Enders. Freiburg/München 2015, p. 97.

- Cf. Meister Eckhart: „Liber parabolarum Genesis“, in: Lateinische Werke I, Stuttgart 1964, p. 327. The theological presupposition is that the intellect is the highest value in the whole order of living being – which makes it possible to speak of the human being as imago Dei.

- Cf. Meister Eckhart: „Sermo 54“, in: Lateinische Werke IV, Stuttgart 1956, p. 445.

- Cf. Meister Eckhart: „Expositio Sancti Evangelii Secundum Iohannem“, in: Lateinische Werke III, Stuttgart 1994, p. 270.

- Cf. Meister Eckhart: “Predigte 22”, in: Deutsche Werke I, Frankfurt 2008, p. 259.

- Cf. Meister Eckhart: “Predigte 27”, in: Deutsche Werke I, Frankfurt 2008, p. 313.

- Cf. Meister Eckhart: “Predigte 29”, in: Deutsche Werke I, Frankfurt 2008, p. 333.

- Cf. Meister Eckhart: „Expositio in Sapientiam”, in: Lateinische Werke II, Stuttgart 1992, p. 612.

- Cf. Meister Eckhart: „Predigte 104“, in: Deutsche Werke IV, Stuttgart 2003, p. 571.

- Cf. in this connection Michel Henry: „Hinführung zur Gottesfrage: Seinsbeweis oder Lebenserprobung?“, in: Meister Eckhart – Erkenntnis und Mystik des Lebens, Freiburg/München 2008, pp. 64-78, here p. 73.

- Cf. Rolf Kühn: „Lebensmystik. Ursprüngliche Erfahrungseinheit von Religion und Ethik im Spiegel ‚philosophischer Mystik‘“, in: Radikalphänomenologische Studien zu Religion und Ethik. Dresden 2018, p. 74.

- Cf. Rolf Kühn: Ibidem, p. 44. Cf. also Michel Henry: C’est moi la vérité, p. 75.

- Self-experience of Life has a ‘passive’ character because Life is generated without creation-acts in the causal sense of the term (where the effect is separated from its cause); it is at the same time the highest ‘act’ because life-generation out of an absolute source can only come from a divine being that knows no separation and (perpetually) creates in the non-causal immanence of its own power.

- John Woodroffe’s assimilation of Tantra and Veda in terms of Yuga-Śāstras is a clear example of this strategy that ultimately tended to make Hinduism compatible with English Protestantism (cf. Arthur Avalon: Principles of Tantra, Madras 1962, pp. 41-42, and also Kathleen Taylor: Sir John Woodroffe. Tantra and Bengal. ‘An Indian Soul in a European Body?’, London/New York 2001, pp. 176-177.

- Cf André Padoux: Comprendre le tantrisme. Les sources hindoues. Paris 2010, p. 27, also Hugh B. Urban: The power of Tantra. Religion, Sexuality and the Politics of South Asian Studies, New York 2010, p. 4.

- The term kula points to the clan as a pool of divine forces, which means that there is no distinction between the reunion of the adepts and the manifold energies of the Goddess brought together by the ritual. Kula could in this sense also be taken as a group of (activated) divine forces.

- Cf. David Gordon White: Kiss of the Yogini. ‘Tantric Sex’ in its South Asian Contexts, London 2003, p. 6.

- Cf. Urban: The Power of Tantra, p. 21.

- Cf. in this respect André Padoux: Comprendre le tantrisme, p. 43, and David Gordon White: Kiss of the Yogini, p. 28. For the relationship between local and tribal traditions as the background of Yoginī cults, cf. Vidya Dehejia: Yoginī Cult and Temples. A Tantric Tradition, Delhi 1986, especially pp. 1-2.

- The bond between the yakṣinīs and the world of vegetation makes them strictly ‘local spirits’, that is, spirits related to very concrete natural settings – for which reason the word ‘spirit’ does not appear adequate to translate the term. As to the ‘mothers’, their earliest recorded appearance in Mahābhārata (III, 213, 214 and 219) already underscores their allegiance to non-Brahmanic gods (Skanda) as well as their ambivalent character (they are sent to kill him, but they feed and nurture him).

- David Gordon White speaks of ‘vulval essence’ (cf. Tantra in Practice, Princeton 2000, p. 16).

- In Tantrāloka (29.128b) Abhinavagupta mentions the ‘purity’ of fluids because of their proximity to consciousness (cf. John Dupuche: The Kula Ritual as Elaborated in Chapter 29 of the Tantraloka, Delhi 2003, p. 181, note 2).

- Cf. In this respect, see among others David G. White: Kiss of the Yogini, p. 13.

- Cf. Arthur Avalon’s introduction to The Serpent Power. Being the Sat-Cakra-Nirupana and Paduka-Pancaka. Two works on Laya-Yoga, edited and translated by Arthur Avalon (Sir John Woodrooffe), New York 1974, p. 31, and also The Kaulajnananirnaya, The Esoteric Teaching of Matsyendrapada, edited and translated by Pandit Satkari Mukhopadhyaya in collaboration with Stella Dupuis, New Delhi 2012, p. 85.

- It should be noted that in the Tantric practice of visualization of Deities [dhyāna], images are not at all conceived as ‘abstractions of the spirit’, but rather as ontological concretions. The same applies to the (phonic) ‘substance’ of mantras.

- Cf. David Gordon White: Kiss of the Yogini, p. 79, and also André Padoux: Comprendre le tantrisme, p. 40.

- “In the shaivite traditions of Kula, the deities inhabit the body and animate the senses”, André Padoux: Comprendre le tantrisme, p. 124.

- Cf. Hugh Urban: The Power of Tantra, pp. 19-20.

- Cf. Hugh Urban: Ibidem, p. 102.

- Cf. Jean-Pierre Chaumeil: « Une façon d’agir dans le monde. Le chamanisme amazonien », in : D’une anthropologie du chamanisme vers une anthropologie du croire Hommage à l’oeuvre de Roberte Hamayon. Sous la direction de Katia Buffetrille, Jean-Luc Lambert, Nathalie Luca et Anne de Sales (Études Mongoles & Sibériennes Centrasiatiques & Tibétaines), 2013, pp. 109-135, here pp. 115–117.

- Cf. Jean-Pierre Chaumeil: « Sobre la etnografía amazónica. La monografía como proceso de construcción permanente (El trabajo de campo entre los Yagua, Perú)”, in: Revista de Dialectología y Tradiciones Populares, (vol. LXIII, n.1, enero-junio 2008), pp. 237-248, here p. 244-245.

- Cf. Philippe Descola: La composition des mondes. Entretiens avec Pierre Charbonnier, Paris 2014, pp. 207-208, and also Philippe Descola: Une écologie des relations. Paris 2019, p. 46.

- Cf. Philippe Descola: Par-delà nature et culture, Paris 2005, p. 187.

- Cf. Eduardo Viveiros de Castro: Cannibal Metaphysics. For a post-structural anthropology, translated and edited by Peter Skafish, Minneapolis 2014, p. 68.

- Cf. Viveiros de Castro: Ibidem, p. 69

- Cf. Elsje Maria Lagrou: Cashinahua Cosmovision: a Perspectival Approach to Identity and Alterity, St. Andrews 1998, p. 31: “For Amerindians the universe is transformative. This means that vision can suddenly change before our eyes. The world is also understood to be multi-layered, several worlds are thought to be simultaneously present and always connected, although not always perceptible”.

- Cf. Viveiros de Castro: The Relative Native. Essays on Indigenous Conceptual Worlds, Chicago 2015, p. 234. This does not mean that a subject literally creates other beings (since that would be a ‘representation of creation’ with fixed poles: creator and created). It means rather that other beings are concretely and dynamically impregnated by the perspective of each subject (all of them are at the same time creators and created), since each perspective opens a whole world of relations.

- Cf. Lagrou: Cashinahua Cosmovision, p. 30, and also Viveiros de Castro, Cannibal Metaphysics, p. 66; Viveiros de Castro, The Relative Native, p. 268 and p. 278.

- Cf. Viveiros de Castro: The Relative Native, pp. 209 and 229.

- Cf. Viveiros de Castro: The Relative Native, p. 284.

- Cf. Viveiros de Castro: Cannibal Metaphysics, p. 60.

- The Brahmanization of Tantra and its increasing inclusion in philosophical systems after the model of the six darśanas marks a transition from a dominant animism to a significant analogical input. Such transitions and composite forms of cult and practice would demand another whole essay.

- Cf. Philippe Descola: La composition des mondes, p. 251.

- Cf. Adrián Navigante: Das Problem der Selbst-Affektion in nicht-christlichen Religionen am Beispiel des Hinduismus, in: Jahrbuch für Religionsphilosophie (Band = 16), p. 118.

- The reader should be reminded that the concept of Life-World [Lebenswelt] was coined by Husserl at the end of his life – more precisely, in his approach to the crisis of the European sciences (1936) – questioning many of the aspects criticized by Michel Henry’s Phenomenology of Life. Cf. Edmund Husserl: “Die Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften und die transzendentale Phänomenologie”. In: Gesammelte Ausgabe. Band VI, Haag, 1970, esp. p. 70.