- » Jacques Cloarec, Editorial

- » Adrián Navigante, Eros Counterpointed: Henri Michaux’s Vision of Cosmic Voluptuousness and Alain Daniélou’s Divinization of Eroticism

- » Dossier: Bettina Bäumer at the Labyrinth

- » Gioia Lussana: The Touch of the Goddess

- » Chiara Policardi: Śaiva Yoginīs and their Animal Faces: Remarks on Origins and Meanings

- » Sarah Kamala Sadacharan: A Note on the Dravidian South: Caste System and Classical Literature

A NOTE ON THE DRAVIDIAN SOUTH: CASTE SYSTEM AND CLASSICAL LITERATURE

Sarah Kamala Sadacharan, indologist, university of munich

The caste system in Tamil Nadu is distinguished from that of the northern part of India, especially regarding the question of hierarchy. The status and role of Vellalars (ancient land-owning community) became a model for the Tamils, whereas any designation of Brahmins by the name ‘Tamil’ was forbidden. In the ‘Dravidian South’ the caste system was not acknowledged as such, though discriminating Tamils and Brahmins played a considerable role in the discourse of Tamil identity. In this contribution, Sarah Kamala Sadacharan shows how the Tamil identity was formed through the arts (poetry, drama and music) and preserved within the context of classical literature.

The problem of caste in the Tamil context: peasants and power

The caste system in southern India is not like that of the North. The typical designations and divisions found in the “Aryan”1 caste system are not entirely applicable to Tamil society. The origins of the social hierarchy in Tamil Nadu relate to the type of society that existed there in ancient times. According to representatives of the “invasion theory”2, ancient Tamil Nadu society differed consistently from northern standards in many ways: “Most authors on the Sangam age describe Tamil society as clearly stratified in a rudimentary form of caste system with limited endogamy and few interdictions on commensality”3. This system was not the result of a process, but something that remained unchanged since the beginnings of that civilization. The caste system in Tamil Nadu distinguishes itself from the northern part of India not only in its generalities, but also in the question of hierarchy according to function. We illustrate this aspect by taking the example of the Vellalars (ancient land-owning community), who were very important for that society and, albeit peasants, had ruling social power.

At the time of the migrations from the northeast, tribes were socially differentiated from town-dwellers. Quite early on we already find, besides the free tribesmen [viś], a tribal nobility and warrior group, which, in due course, produced the tribe’s prince [rāja] and priest [brahmana]. During their ethnic settlement, the dominant Aryas interacted with the aboriginal people, who nonetheless carried out important activities as day-labourers and artisans. The most decisive criterion for delimiting the three first groups of the caste system (the Aryas: brahmana, rājanya, vaiśya) vis-à-vis the oppressed aboriginals was the darker complexion of the latter. Caste division was based on discrimination according to skin colour [varṇa]. The four varṇas were at the beginning social strata, into which the actual castes were later incorporated and ranged4. In south India, these strata were structured as tribal societies with chieftaincies and kings, in which Brahmins gained increasing influence. The Sangam-Literature shows the conflict between these two models of society: Aryan and Dravidian5.

Brahmanic society became more powerful after the invasion of the Aryas from the north, replacing the tribal societies’ bards and singers and gaining a position of influence with the rulers. The bards and singers entertained the kings and recited hymns for them, for which they were well remunerated. The royal milieu also included generous patrons and officials who owned land and properties and maintained cultural and social standards: “The people who enabled poems to be sung, who enabled singers to survive, who upheld culture and society were chiefs and landowners or farmers. Later, the chiefs were called Vellalars. They were the caste of farmers in the Chola period”6. The Tamil kingdom of Chola flourished from the IX to the XIII Century. It was one of the most influential Hindu kingdoms with a vast area of influence from southern India to southeast Asia. It is very often mentioned in the Sangam literature.

Agriculture was particularly important for the whole land. In the Brahmanic legal code called Manudharma, which is the most ancient source dealing with the institution of caste, farmers are called śūdras, i.e. the lowest rank in the caste system. As early as the hymns of the Rigveda the four castes are treated within a creation myth that also deals with the institution of sacrifice. The following account played a very important role in Hindu society after the Vedic period: “this Puruṣa is all that yet hath been and all that is to be. […]So mighty is his greatness; yea, greater than this is Puruṣa. All creatures are one-fourth of him, three-fourths eternal life in heaven […]. With three-fourths Puruṣa went up: one-fourth of him again was here. […]The brahmana was his mouth, of both his arms was the rājanya made. His thighs became the vaiśya, from his feet the śūdra was produced” (RV, X, 90).

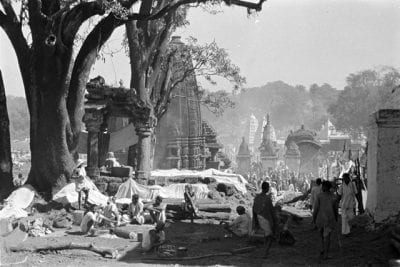

Amarkantak

AmarkantakPhoto: alain daniélou / raymond burnier

The cosmos (Puruṣa) contained everything, and within this order the śūdras’ position is at the lowest level. We are here faced with a mythological account of the origin of caste according to Vedic religion. The Vedas were composed in Sanskrit and are one of the most important models of classical Hinduism, but in Southern India they were never acknowledged as such by the Dravidian people. Later, during the British Raj, artisans, farmers and other workers fell within the category of śūdras, but the Vellalars did not call themselves by that name, since it did not recognize the importance of the role and position of farmers in Tamil Nadu. While farmers in northern India belonged to the lowest caste, agriculture in Tamil Nadu was highly regarded and farmers were greatly respected7. From ancient texts we gather that the farmers contributed to the fertility of the land: “[…]as Karkatta [cloud-bringing] Vellalars attract rains by instituting ritual and sacrifice. Their activities and goodwill guarantee the life and well-being of all, ultimately the world”8. They were entitled to carry out rituals and sacrifices, which in northern India were the exclusive right of Brahmins. The farmers were the most important caste in preserving a functional society, interacting also with the gods. Even the king was obliged to revere them. Brahmins in Tamil Nadu, on the contrary, were not recognized as part of society, even if they sang and spoke in Tamil.

Whereas the distribution of social functions in Aryan society led to the formation of a high caste of priests, a caste of warriors and a lower caste of farmers, the situation in southern India was exactly the opposite: warriors were degraded as mercenaries and criminal tribes, whereas landowners and countrymen formed the second caste after the Brahmins. The status and role of Vellalars became a model for the Tamils. Actually, they were the ‘ultimate Tamils’, whereas any designation of Brahmins by the name ‘Tamil’ was forbidden9. This shows us that the caste system in southern India was not acknowledged as such.

Anyone, with exception of Brahmins, could become a Vellalar. The only requisite was to follow the religion of the Vellalar Shaivites: “The resultant identity was not primarily based on ancestry and birth; but – and it’s a large ‘but’ – Brahmans were excluded because they were not of the right i´am. In Tamil i´am could become Vellalars, except the Brahmans, because they were Aryan”10. The Vellalar society was not exclusive like that of the Brahmins. Anyone who had access to land and was not Brahmin could become Vellalar.

In the discourse of Tamil identity, discrimination between Tamils and Brahmins plays a considerable role. The question of identity only emerges when someone has an opposite from which he/she has to differentiate himself/herself (the more aggressive the differentiation, the stronger the identity affirmation). Language also plays a decisive role in the construction of Tamil identity. When Tamil was recognized as a classical language and thus ranked on the cultural scale with a value similar to that of Sanskrit, the conflict between Aryans and Dravidians and the question of inter-group discrimination removed to the linguistic level. This modality of consciousness and self-affirmation shows that Tamil identity is not held so much for itself, as in opposition to ‘the other’.

Development of self-consciousness could begin with knowledge of ancient texts and Tamil culture in general. For this reason, the Tamil writer Maraimalai Atikal (1876-1950) said that Tamils should not compare themselves to Brahmins but rather found their own culture on a deeper level.

Classical Literature and Tamil Identity

What form of consciousness led the Tamils to cultural autarchy? We could say that it emerged within the context of Tamil literature and culture. Legend says that poetry academies (sangams) cultivated Tamil literature on the ‘Kumarikkandam’ continent, hence the earliest stage of development of Tamil literature (from circa 200 BCE to 300 CE) is called Sangam literature. Many works of different genres (poetry, epics) stem from this period. They can be traced back, at least in part, to earlier oral transmission: “apart from some epigraphic and archaeological evidence, the classical literature is the most important native source of historical and cultural information for this period in Tamil South India”11. A whole mythology around the poetry and poets of Sangam literature arose from native sources.

After a long period of emergence, classical Tamil literature was composed by scholars whose works were collected. Around the year 1000 CE, they fall into oblivion as a result of the prominent role of other religious influences. At the end of the Sangam period, influences of northern India on Tamil literature become conspicuous – i. e. texts written mostly in Sanskrit dealing with subjects found extensively in Buddhist and Jain writings. In the XIX century, the texts were rediscovered, and greatly interested Western scholars.

Temple of mahābalipuram, tamil nadu

Temple of mahābalipuram, tamil naduPhoto: Jacques Cloarec

Another important factor that might explain why ancient Tamil literature fell into oblivion was the strong influence of militant Brahmanic Hinduism. Supporters of Shaivism and Vishnuism in the late Middle Ages forbade these (which?) texts: “[…]they tabooed as irreligious all secular texts; they disallowed from study all Jain and Buddhist texts [which also included the Cilapatikaram]12. All non-Hindu texts (including Tamil ones) were forbidden.

Tamil literature underwent very strong changes under Western influence during European colonial domination. New genres, such as novels, essays and short-stories became prominent in the late XIX and early XX Century and permeated modern Tamil culture. R. Krishnamurty (1889-1954), also called ‘Kalki’, wrote short-stories especially on historical subjects. Subramaniyam Bharati (1882-1921) is reputed as one of the most extraordinary modern Tamil poets. His disciple Bharati Dasan (1891-1964) was one of the most influential figures on Tamilavan and one of the most important Tamil critics of the XX Century. All of them made use of this ‘new’ genre13. The term ‘Tamil’ appears in the context of classical literature; the roots of the language and local identity also lie in the ancient texts. Precisely for this reason it is supposed that Tolkāppiyam (the earliest extant text on Tamil literature and linguistics, presumably from the III century BCE) is the source of Tamil14.

The so-called muttami (threefold Tamil) is divided into poetry/speech, drama and music. It was considered to be of divine origin, created either by Shiva or Skanda Murugan (son of Pārvatī and Shiva). Very early on in history, Tamil scholars distinguished the everyday language (koṭuntamiḷ] from the polished literary style or poetic register [centamil]. Around the same time, it was perceived that language did not only consist of the oral part, but also of music, gestures and mimicry. Thus emerged a division between ‘inner’ [akam] and ‘outer’ [puram] poetry, which classified ‘inner poems’ as poems of the heart and of love, as opposed to ‘outer poems’, related to kings, warriors and battles15. The point of departure was a sort of ideal human being, described from a universal standpoint. But even on this subject there were different views: Tamil poets on the one hand, who believed the ancient theories about love, and Vedic scholars on the other, who rejected that view. Iraiyaṉār’s commentary on Akapporul (a Tamil work on grammar) says that Shiva was the patron of the disciplines [sanigam] of Tamil poets16. He is also seen as the source or even the creator of the language. Tamilavan also writes: “Subramaniya Bharati described Tamil as the language that stems directly from the omnipotent Shiva”17.

In spite of the adaptation of Indo-Aryan words and their undeniable influence on the Tamil language, the literary style of Tamil Nadu – based on local ancient sources – was something quite particular. As Charles Ryerson points out, “The leaven of Indo-Aryan was working in Tamil as in all other Indian non-Aryan speech, but although Indo-Aryan […]words were being adopted […]Tamil developed a literary mode of its own which is essentially South Dravidian”. This South Dravidian style presents some features pointing to the original self-awareness of Tamil identity, a kind of primordial consciousness whose roots are purely Tamil. Of course there are those who affirm that Tamil is not an independent language.

- The term “Aryan” was an ethnic label used to designate the group of Indo-Iranian people in Vedic time.

- According to the invasion theory, there were migrations of non-Indian light-skinned (Aryan) peoples in the Subcontinent towards the year 1500 BCE, which overthrew the aboriginal (Dravidian) civilisation of the Indus Valley and established a culture that can be traced back to the Vedas.

- Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar: Is there a Tamil “race”? in: Robb, Peter: The concept of race in South Asia, Delhi, 1997, p. 123.

- Kulke, Hermann und Rothermund, Dietmar: Geschichte Indiens: Von der Induskultur bis heute, München 1998, pp. 56-57.

- Ryerson, Charles A.: Regionalism and Religion: The Tamil Renaissance and Popular Hinduism, Madras 1988, p. 61.

- Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar: Is there a Tamil “race”? in: Robb, Peter: The concept of race in South Asia; Delhi 1997, p. 123.

- Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar: Ibidem., p. 123.

- Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar: Ibidem., p. 124.

- Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar: Ibidem., pp. 125-126.

- Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar: Ibidem., p. 128.

- Ramanujan, A.K.: Poems of Love and War, from the Eight Anthologies and the Ten Long Poems of classical Tamil, New York 1985, pp. 85-86.

- Zvelebil, Kamil: Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature in: Spuler, B. (ed.): Handbuch der Orientalistik, Leiden 1992, p. 147.

- http://www.tamilar.org/tamil-language.asp, (viewed on March 20, 2015).

- Zvelebil, Kamil: Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature in: Spuler, B. (ed.): Handbuch der Orientalistik, Leiden 1992, Einführung.

- Bate, Bernard: Tamil Oratory and the Dravidian Aesthetic: Democratic Practice in South India, New York 2009, p. 170.

- Stein, Burton: Circulation and the Historical Geography of Tamil Nadu, In: Journal of Asian Studies, Michigan 1977, p. 8.

- Tamilavan: Tamil unarvukku enna porul, in: Tamilunarvin Varaipatam, Chennai 2009, p. 17