- » Jacques Cloarec, Editorial

- » Adrián Navigante, Eros Counterpointed: Henri Michaux’s Vision of Cosmic Voluptuousness and Alain Daniélou’s Divinization of Eroticism

- » Dossier: Bettina Bäumer at the Labyrinth

- » Gioia Lussana: The Touch of the Goddess

- » Chiara Policardi: Śaiva Yoginīs and their Animal Faces: Remarks on Origins and Meanings

- » Sarah Kamala Sadacharan: A Note on the Dravidian South: Caste System and Classical Literature

ŚAIVA YOGINĪS AND THEIR ANIMAL FACES: REMARKS ON ORIGINS AND MEANINGS

Chiara Policardi

Chiara Policardiposition?

Yoginīs are frequently represented in therianthropic form – with animal faces or, more rarely, with a wholly animal appearance – in Śaiva Tantric texts and in sculptures enshrined in the circular mediaeval temples dedicated to them. This representation raises several questions. Why are these sacred female figures often conceived and represented with animal traits? What is the origin of this mode of representation? What meanings and implications lie behind these portrayals? Chiara Policardi approaches these questions with competence and insight, considering the origins of the animal-faced mode of representation and discussing the possible meanings of this form.

Ambivalent, multiple, manifesting on the borders of wilderness and after transgressive rituals, capable of deeply transforming their devotees, and – peculiarly – often represented with seductive feminine bodies but animal faces: these are some of the characteristics of the yoginīs. This group of goddesses or demi-goddesses ‒ studied only since relatively recent times ‒ is closely associated with the Tantric phenomenon, and the yoginī figure emerges primarily in the Hindu Śaiva domain.1

The Śaiva cult of yoginīs flourished to its greatest extent from the eighth to the twelfth centuries CE. Although Tantric practices connected to these sacred figures are attested both before and beyond this period, it was in these centuries that the primary scriptures relating to yoginīs were composed. In these texts, the term yoginī is used to designate both powerful goddesses and female adepts who ritually embody the deities. In fact, female divinisation represents a distinctive trait of the Tantric yoginī cult.

Originally pertaining to strictly esoteric cultic contexts, the phenomenon of yoginīs subsequently became widespread and achieved prominence in the broader Indic religious landscape. Two different kinds of evidence prove this process: on the one hand, the yoginīs were incorporated in the Purāṇic literature, a sign of the attempt to incorporate the cult into the “orthodox” tradition, while, on the other, they received royal patronage.

Historically, these mediaeval centuries represent a period of extreme political instability, in which states quickly rose and died and tribal kingdoms tried to elevate themselves on the fluid political map ‒ its borders continuously re-defined by ongoing regional warfare. This climate of fraught uncertainty has probably been a factor for exponents of royal families to turn their devotion to yoginīs. They addressed these potent goddesses for protection, success in military actions, and achievement of political stability, thus contributing to no small extent to the blossoming of the yoginī cult. It was thanks to royal patronage, indeed, that from the end of the ninth through to perhaps the thirteenth century monumental stone temples dedicated to yoginīs were erected over the entire Indian subcontinent.

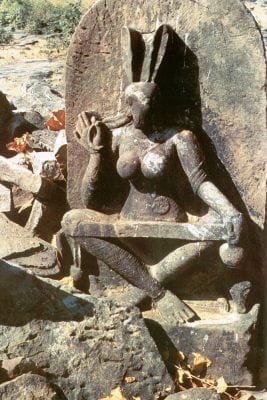

These shrines stand out as unique structures in the architectural panorama of mediaeval India: hypaethral and circular-shaped, their entire internal perimeter is sectioned by a series of niches that house the goddesses’ images (Figure 1). These sculptures usually present sensuous feminine bodies, but, whereas some of them have finely delineated, gentle faces that complete their beauty, others show terrifying expressions, and several others have clearly non-human, animal faces (Figures 2, 4, 5, 6, 7).

This theriocephalic representation of yoginīs finds attestation in textual sources as well. Tantric Śaiva texts related to yoginīs belong to two main corpora: that of the Vidyāpīṭha (“Female Mantra-deities Corpus”) and that of the Kaula (“[Tradition] of the [Goddess]Clans”). The tantras of the Vidyāpīṭha, dating from the eighth-ninth centuries, predate the yoginī temples by at least two centuries, while several Kaula scriptures, post tenth-century, belong to the period of the major yoginī temples. In both these traditions, the figures of yoginīs are frequently conceived and depicted as partly anthropomorphic and partly theriomorphic in form, as an anatomical combination of human and animal traits or, more rarely, with a totally animal appearance.

Thus, yoginīs are often endowed with a dual nature, human and non-human, feminine and animal, at the same time. This coexistence of two natures, this very conception and the mode of representing it, has not been given sufficient attention it merits.

The therianthropic form of yoginīs poses to the modern reader and observer several and manifold questions. The question that is both the most immediate and, so to speak, the ultimate question pertains to a why, as often happens in research: why are the yoginīs often imagined and represented with animal traits in texts and images? Or, in other words, why are these deities so closely intertwined with animals?

What is the origin of this mode of representation? Are the yoginīs inheritors of a particular tradition, as is often the case in Indian religious and cultural expressions?

How does this composite form relate to their functions? Is it meaningful to find as a rule a key body part such as the face occurring in animal form? What meanings and implications lie behind these portrayals?

These questions, which could be ramified and multiplied, frame complex and wide-ranging issues: what follows is not intended as an exhaustive discussion but as illustrative remarks. After considering the origins of the therianthropic mode of representation, attention will focus on the possible meanings of this form, in particular on the hypothesis of an animal mask of the yoginīs.

Ram-faced yoginī from Lokhari, Uttar Pradesh. New Delhi National Museum

Ram-faced yoginī from Lokhari, Uttar Pradesh. New Delhi National MuseumPhoto: Virtual collection of asian masterpieces, 2013

The antecedents of yoginīs and their animal faces

The peculiar mode of conceiving and representing the yoginīs that combines animal and human in a composite anatomy does not appear ex nihilo. As often happens in Indian cultural history, the yoginīs are inheritors of an earlier tradition. As a deity typology, the yoginīs demonstrate remarkable continuity with precedent, non-Tantric figures. Among the possible historical antecedents of therianthropic yoginīs, three classes of figure emerge as the most prominent: gaṇas, yakṣiṇīs, and mātṛs. These conceptual and figurative models historically contribute to the formation of the yoginī figures, converging in this class of Tantric goddesses around the seventh century.

As is well-known, the gaṇas are a group of beings belonging to the retinue of Śiva. Featuring especially in Purāṇic texts and in friezes on the base of Hindu monuments, they are described and represented with varied appearances, but, interestingly, they are often represented with animal and bird heads or faces. According to the myth, Śiva conferred the leadership of these beings to a figure whose most distinctive trait is an animal head, namely Gaṇeśa.

The foremost characteristics that gaṇas share with yoginīs are precisely their nearness to Śiva and their animal features. Moreover, both gaṇas and yoginīs have supernatural powers and may behave as spirits of a possessing nature. However, while the yoginīs are frequently considered as deities tout court, the gaṇas are figures surrounding a god rather than gods themselves. Indeed, usually, they do not receive any direct cult.

Instead, from indeterminably early times, cult is paid to the yakṣiṇīs or yakṣīs, a class of demi-goddesses usually regarded as having local, regional or non-Brāhmaṇical origins. As is well-known, these deities are intimately connected with the natural world and in particular with vegetation and water. They are believed to dwell in trees,2 and may be considered as the personification of the life-giving essence of the tree, the sap. Moreover, according to several textual sources, the yakṣiṇīs possess supernatural powers, which they may bestow on humans, and are capable of changing their form at will; also, they are sometimes regarded as spirits of a possessing nature.3

Besides supernatural powers, instability of physical form, and their possessing nature, yakṣiṇīs and yoginīs also share an ambivalent character, and the iconography of yoginīs in some cases is informed by vegetal motifs – the most significant examples are found in the Hīrāpur temple in Orissa –, while Tantric texts mention yoginīs that reside in trees or may use the terms yoginī and yakṣiṇī interchangeably.4

While theriocephalism is not the most conspicuous trait of yakṣiṇīs , since an association with flora rather than with fauna is their hallmark, animal-faced representations are relatively abundant among early depictions and textual descriptions. An interesting representative of this therianthropic yakṣiṇī typology is Aśvamukhī, a yakṣiṇī peculiarly represented as horse-headed in texts and images. She features in a Pāli jātaka as the mother of the Buddha-to-be, and is portrayed on several art-historical records, both Buddhist and Hindu, usually in the act of detaining a young Brāhmin (Figure 3). She is a clear example of how very early in the history of Buddhist phenomena these local beings were incorporated into Buddhist religious beliefs, imagery, scriptures, and art.5

While gaṇas and yakṣiṇīs represent significant antecedents, in the genealogy of yoginīs the most immediate precursors are to be seen in the figures of mātṛs.

Since early times a rank of female deities called simply mātṛs, “Mothers”, has been venerated throughout the entire Indian subcontinent. Among the earliest textual sources on these deities, the Mahābhārata describes the mātṛs as dangerous, wild, and countless figures.6 These Mother goddesses are initially not affiliated to a specific religious tradition, as testified by material records portraying them found in cultic complexes of various sectarian orientations. In the early phases of their cult, the Mothers are deities intimately connected to birth and childhood, fertility and life, but also to sickness and death, embodying the well-known religious conception of a deity that is simultaneously a life-giver and a death-dealer. They are indeed characterised by an ambivalent nature, and are helpful if propitiated, baneful if angered.

From an initial association with Skanda and Kubera the mātṛs subsequently shift toward a more decidedly Śaiva affiliation. Moreover, by the Gupta age a particular group of seven Mothers (saptamātṛs) emerges. These goddesses are conceived and represented as śaktis, hypostases, of the major Brāhmaṇical male gods, assuming name, emblems and mount of the corresponding god. This transformation is clearly the result of assimilation by the Brāhmaṇical tradition. Nonetheless, in such a religio-historical development, the early mātṛs transmit their original characteristics to yoginīs. As Hatley (2012: 110) has effectively captured, “[t]he yoginīs’ theriomorphism, shapeshifting, multiplicity, extraordinarily variegated appearances, bellicosity, independence, and simultaneous beauty and danger all find precedent in these early Mother goddesses”. Indeed, throughout the eighth century, while the mātṛs as an independent group of deities were gradually receding into the background, losing importance in worship, in parallel, the cult of yoginīs was assuming definite contours, relevance, and diffusion.

One of the most conspicuous strands of historical continuity between mātṛs and yoginīs lies in their theriocephalic representation. In numerous cases, the Mothers are depicted in a composite form and with infants having corresponding animal faces. Significantly, various sculptures of yoginīs show a similar maternal iconography, in which an animal-faced infant seats on the knee or on the hip of the theriocephalic goddess.

Interestingly, some sculptures of yoginīs characterised by such maternal iconography also bear emblems related to the sphere of death, which clearly derive from the Kāpālika influence on the yoginī cult, thus creating an ambivalent image. This is the case of a sculpture from Lokhari (Figure 4): the yoginī is represented as jackal-faced and a similar animal-faced child sits on her lap. Both mother and child are depicted in the act of howling. In one hand the yoginī holds a skull-vessel, while a human corpse lies beneath her seat. In this image, the face of a jackal, an animal peculiarly connected with cremation-grounds, the skull-cup and the corpse clearly refer to death imagery, which is however merged with the typical maternal iconography of mother with child.

Hence, the yoginīs owe their composite form to the continuity of tradition: they clearly inherit this feature from precedent, non-tantric figures. As White (2000: 30) writes, referring to yoginīs, ḍākinīs, rākṣasīs, bhūtas, pretas and the like, “when their cults became ‘tantric’ – or when Tantra emerged out of their cult practices – is a chicken/egg question that is impossible to resolve”.

Nonetheless, both textual and iconographic sources show that the animal component is not a meaningless hereditary trait in yoginī figures, but has a powerful position within the Tantric and, more generally, Śaiva discourse. Indeed, the relationship between the three classes of beings identified as precursors of yoginīs and yoginīs themselves can be interpreted in the frame of the hermeneutical category of “reuse”. The theriocephalic representation of yoginīs can be read as a previous, traditional form that is resemantised in the Tantric context. Precedent typologies of deities, and in particular the category of goddesses known as mātṛs, experience a process of transformation and resemantisation over the course of time, finally emerging as yoginīs in the Tantric tradition. It is a phenomenon of reuse and reinterpretation of previous forms, which acquire new meanings in a new religious context. The very fact that a specific form ‒ in this case the animal-human combination ‒ is updated and reused attests its vitality and significance.

Significance and meanings of therianthropism in the Śaiva yoginī cult

What is, therefore, the meaning and significance of the therianthropic form of yoginīs in the Tantric context?

The yoginīs’ therianthropism is essentially related to the coexistence of their two natures, the human and the animal, within a single composite anatomy. In a minor number of cases such coexistence is expressed in a shapeshifting ability from anthropomorphic appearance to theriomorphic and back. Hence, it is not only the animality of the figure that is relevant, but above all its duality, its ambiguity, its nature that simultaneously contrasts and synthesises two different categories of beings. In this way, too, opposite conceptual categories are made contiguous, such as nature-culture, wild-domesticated, irrational-rational, and the like. In general, therianthropic deities are often surrounded by a condition of tense ambivalence. In different religious contexts, animal-human figures, as a typology of beings whose elements are neither separate nor unified, are frequently associated with rituals of transition and liminality, such as initiation rites for instance.

Sloth bear-faced yoginī, Hīrāpur yoginī temple, near Bhubaneśvar, Orissa

Sloth bear-faced yoginī, Hīrāpur yoginī temple, near Bhubaneśvar, OrissaPhoto: Stella dupuis

The combination of different beings in a composite anatomy might be reminiscent of the category of monstrosity. However, the sensuous bodies of yoginīs in sculptures elude this possibility, for they give form to figures that juxtapose the fascination of the feminine and the unpredictability of the animal, conveying a simultaneous sense of attraction and inquietude. Also textual descriptions of therianthropic yoginīs often express such an ambiguity between beauty and terror.

The textual and iconographic material concerning the animal aspect of these figures is very elusive, and does not lend itself to a straightforward interpretation. Indeed, ambiguity and polysemy appear as inherent features of yoginīs. On the one hand, yoginīs are highly dangerous beings, but on the other, in certain circumstances, they can bestow the highest spiritual realisation to the practitioner and grant all his desires within a very brief period of time.

In an attempt to plumb the conceptual world that has generated these richly expressive therianthropic forms, as far as the meaning and significance of the animal-human form of yoginīs is concerned, it is possible, in my view, to identify three lines of interpretation, which are intended as interlocking and not mutually exclusive. These can be subsumed in few key words and organized in three sets: (1) metamorphosis, melaka, and supernatural powers; (2) liminality, wilderness, and otherness; (3) an animal mask?

An Animal Mask?

Among these, I will fous on the hypothesis of an animal mask, which has not been advanced in previous studies.

The form and concept of a mask are strongly suggested by iconographic depictions of yoginīs. Analysis of the single sculptures reveals that in some instances the head is wholly theriomorphic, but in several cases an animal face is combined with other components of the head, such as the hair and the ears, that appear clearly human. In other words, only the outer surface of the head is depicted as animal-like. Particularly significant examples of this animal-human juxtaposition are found in the temple of Hīrāpur, in Orissa (Figure 5), in the shrine of Bherāghāṭ, in Madhya Pradesh (Figure 6), and among the statuary from Lokhari, in Uttar Pradesh (Figures 2, 4, 7).

Hare-faced yoginī, from Lokhari,Uttar Pradesh

Hare-faced yoginī, from Lokhari,Uttar PradeshPhoto: after dehejia, v., 1986. yoginī cult and temples. a tantric tradition, delhi: national museum, p. 158

If animal-faced yoginī representations hint at an animal mask, who is the figure wearing that mask, a deity or a woman? And why is she wearing it? Do yoginī-related texts offer evidence to unravel the issue?

As a matter of fact, the texts do not appear to offer decisive evidence to unravel the issue. There are no explicit hints pointing towards the idea of an outer surface that conceals or disguises the face of an entirely human or anthropomorphic being. However, as Shulman (2006: 20) remarks, in India a specific word for “mask” is lacking. He observes that the languages of India refer to that part of the guise that primarily concerns the head simply as “face” (mukha, ānana, āsya, etc.). Is it, then, possible that behind the designations for animal-faced yoginīs there is a reference to a mask? Possibly yes, but far from being certain. If masks were employed in the yoginī cult, would they be more explicitly attested in texts? Not necessarily: Indological studies show that in several cases art-historical or visual records attest facts or usages that do not find evidence in texts, and vice versa.

Thus, texts leave a possibility open, while iconographic sources present strikingly peculiar features that call for an explanation. The cases are striking and numerous enough, I believe, to make the hypothesis of a mask plausible. Not only are they striking and numerous, but they are also found at distant geographical locations (Orissa, Madhya Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh) and are attested from rather distant chronological periods (from ninth century to eleventh century): thus, they are not limited to a single temple tradition.

What could be, then, the meaning of this mask-like form?

The divine status of yoginīs in sculpture is suggested by the multiple arms exhibited in several cases. Thus, it is not rare to find an animal-faced yoginī presenting four or more arms. As is well-known, in Indian art the multiplicity of bodily parts is a clear indication of divine status. If the animal-faced yoginī is a goddess, then, why is she wearing a mask? As a divine being, she does not need a mask to transform herself: she possesses supernatural powers, among which the most conspicuous is the shape-shifting power.

In my view, these images may refer to rituals in which human women identify themselves with animal-faced goddesses, ritually behaving as animals and birds, and possibly assuming the guise of the deities they represent. Some texts offer glimpses of rituals in which the practitioner imitates the calls and movements of animals; the most significant passages are found in the Jayadrathayāmala, a Tantra belonging to the Vidyāpīṭha tradition.7

Now, in different religious conceptions familiarity to and identification with animals is a sign of the initiates’ proximity to the realm of the supernatural and divine. In the Śaiva context of the yoginī cult, the imitation of animals appears interwoven with the conception of possession. In the earliest sources on yoginīs, āveśa and cognate terms from the root ā-√viś define an altered state of consciousness, in which the yoginīs possess the initiate. Such an experience is transitory, usually very brief, and always intense. If such a possession is not controlled by the practitioner, it is of a baneful nature, but if the adept himself provokes and controls it, he can obtain knowledge and supernatural powers. This state of possession manifests itself in various external signs, including the imitation of animals in both behaviour and calls. This might indicate that the initiate is undergoing a radical change, shifting away from his ordinary identity.

Did these rituals implying possession on the part of the yoginīs make use of animal masks? As is known, masking, which is probably a universal phenomenon, constitutes a prominent dimension in South Asian traditions and religions. Across the different Indian traditions, the mask, being a means of transitory alteration of physical appearance, allows disengagement from ordinary time and facilitates entry into a different domain. In ritual contexts, the mask is a medium accompanying the transition from one status to another.

Thus, in religious practices connected to yoginīs, women might have worn animal masks to assume the identity of animal-faced goddess yoginīs; in such rituals, the mask might have been a tool to facilitate transformation, both the women’s own transformation and that of the male practitioner. As Shulman (2006: 20) remarks, “the mask is normally considered a technique for transforming identity. […][I]n general, there is a sense of exchanging and expanding, let us say, a human persona to the point where it assimilates or appropriates a divine (or demonic) existence”. In this respect, in yoginī-related practices, the animal, presumably, was not seen as a negative “other”, as a threat of loss of human identity, but as an otherness that allows a redefinition and reconstruction of a new, expanded identity.

We might suppose that animal-faced yoginī sculptures represent simultaneously deities and women, in deliberate ambiguity. Indeed, as said, female divinisation lies at the heart of the cult of yoginīs and, presumably, the categories of human women embodying yoginīs and divine yoginīs were not mutually exclusive units in the minds of early mediaeval Tantric practitioners. Possibly, yoginīs, and also therianthropic yoginīs, straddle the real/imagined divide, in a fluid continuum of reality. If we interpret the sculptures as reflecting an intentional and programmatic overlapping of deities and ritual reality, both the mask-like faces, which appear to be fitted onto human figures, and the multiple arms, which are instead appropriate to a deity, would find an explanation.

In conclusion, the animal appearances represent one of the strongest threads that connect the yoginīs with their antecedents and with a pre-Brāhmaṇical and non-Brāhmaṇical past. At the same time, it seems that in the Tantric terrain this ancient root blossoms, insofar as the animal element irrupts constantly into the feminine world of the yoginīs, carrying multifaceted meanings. In particular, the animal traits of yoginīs may point towards rituals of possession, in which animal masks were used by human women to facilitate identification with animal-faced deities, to induce possession by divine yoginīs, leading the initiate to an altered state of consciousness and, maybe, to an inner transformation.

- Due to its semantic breadth, a caveat is in order concerning the lexeme “yoginī”. It does not express a monolithic concept. In the history of Indian religions the term appears in different scenarios, conveying distinct meanings in diverse socio-historical contexts, thus designating a spectrum of female sacred figures. Indeed, already Dehejia in her pioneering work (1986: 11-35) identifies at least eleven distinct meanings for the term yoginī, which in extreme synthesis can be recapitulated as follows: yoginī as an adept in yoga; yoginī as a partner in cakra-pūjā; yoginī as a sorceress; yoginī as an astrological concept; yoginīs as presiding deities of the internal cakras; yoginīs as deities of the Śrīcakra; yoginī as the great goddess; yoginīs as aspects of Devī; yoginīs as attendant deities of the great goddess; yoginīs as acolytes of the great goddess, corresponding to the mātṛs; and yoginīs as patron goddesses of the Kaulas. As noted by Keul (2013: 12-14), we are not dealing with a case of homonymy ‒ where terms accidentally have the same form but no semantic relation between their meanings ‒, but with a case of polysemy: the different meanings are interconnected, at different levels. In the present paper, as the above suggests, I will refer to yoginīs as a group of goddesses or sacred figures affiliated to the Śaiva Tantric tradition.

- See e.g. MBh XII.163.1.

- See Kessler 2009.

- See Dehejia 1986: 36-38.

- See Policardi forthcoming.

- MBh III.213.41-52; 214.1-17; 219.1-15; IX.43-45; XIII.83-84.

- See Serbaeva 2013: 200; 202.

Bibliography

Behl, B., 1998. The Ajaṇṭā Caves. Ancient Paintings of Buddhist India, London: Thames and Hudson.

Dehejia, V., 1986. Yoginī Cult and Temples. A Tantric Tradition, Delhi: National Museum.

Hatley, S., 2012. “From Mātṛ to Yoginī: Continuity and Transformation in the South Asian Cults of the Mother Goddesses”, in I. Keul, ed., Transformations and Transfer of Tantra in Asia and Beyond, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 99-129.

Hatley, S., 2013. “What is a Yoginī? Towards a Polythetic Definition”, in I. Keul, ed., ‘Yoginī’ in South Asia. Interdisciplinary Approaches, London: Routledge, 21-31.

Kessler, A., 2009. “Yakṣas and Yakṣiṇīs”, in K. A. Jacobsen, H. Basu, A. Malinar, V. Narayanan, eds., Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism, vol. 1, Leiden: Brill, 801-806.

Keul, I., ed. 2013. ‘Yoginī’ in South Asia. Interdisciplinary Approaches, London: Routledge.

Policardi, C., forthcoming. “The Case of the Yakṣiṇī Aśvamukhī: Remarks Between Jātaka and Art”, Rivista degli Studi Orientali.

Serbaeva, O., 2013. “Can Encounters with Yoginīs in the Jayadrathayāmala be Described as Possession?”, in I. Keul, ed.,‘Yoginī’ in South Asia. Interdisciplinary Approaches, London: Routledge, 198-212.

Shulman, D., 2006. “Towards a New Theory of Masks”, in D. Shulman, D. Thiagarajan, eds., Masked Ritual and Performance in South India Dance, Healing, and Possession, Ann Arbor: Centers for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of Michigan Press.

Sukthankar, V. S., et alii, eds. 1933–1966. The Mahābhārata (Critical Edition), 19 vols., Poona: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute.

White, D. G., 2000. Tantra in Practice, Delhi: Motilal