Index

- » Letter from the Honorary President Jacques Cloarec

- » Alain Daniélou’s Philosophical Realism: A lesson in Ars Vivendi, Adrián Navigante

- » Swāmī Karpātrī: The Nation’s Development and Dharma, Himadri Ketu

- » From Spectator to Dancer, Aleksandra Wenta

- » On the Subtle Body in Neoplatonism, Felix Herkert

- » A Talk with Alain Daniélou: Shiva-Dionysos Among Us

Alain Daniélou’s Philosophical Realism: A lesson in Ars Vivendi

Adrián Navigante: Alain Daniélou Foundation Research and Intellectual Dialogue

If we take the term “realism” as an attitude to life based on solid convictions (and not just on whimsical prejudices), we could say there are basically two types. The first is a cold and reductionist realism, whose purpose is to limit experience in order to avoid not only cognitive but also emotional confusion, excessive opinion and wild speculation. The second type is creative and rather expansive, aiming at the cultivation of an understanding closely linked to an increasingly refined perception. The danger of the first type is that it may end up putting a straightjacket on life itself in the name of a meagre Realpolitik. The virtue of the second type is that it may help overcome not only old prejudices but also easily-acquired convictions that ultimately cannot stand the real test of life. Both types share a tendency to mental lucidity combined with a rejection of exacerbated idealism and fantastic thinking, but mental lucidity can sometimes be excessively one-sided. However, it is not true that the exercise of realism in et per se goes hand-in-hand with an impoverishment of imagination and sensitivity. On the contrary, it facilitates the proper use of such faculties to achieve a better, deeper understanding of life itself.

Alain Daniélou’s realism belongs to in the second type, and that is perhaps why his message does not evoke a distant and forgotten past, although many of the concepts he formulated were inscribed in a quite different, almost unrecognizable, context from that of today. Two interpretations of his thought seem to me overly biased and simple, that is, too poor to do justice to his unruly spirit. The first tries to see in Daniélou only the artist, the individualist, the insurgent genius whose activity was to speak and act against convention, conformism, mediocrity, to react, to polarize and to polemize. The second seeks to make him a dull and overcast traditionalist, an unbending mind who opposed everything related to the modern world, as well as to subjective creation and any plurality of viewpoints. The line between these two poles should not be seen as a natural demarcation, but rather as a paradoxical confluence and subtle transformation of them.

Because Daniélou knew how tradition works, he introduced variations in its conception and showed that transmission of real knowledge is – because of its historical inscription – at the same time unity (in terms of its paradigmatic value scale) and plurality (in terms of its configuration dynamics). Because he knew that the only type of knowledge that is worth having is that of an integrated life in theory and practice, he always sought to question his own convictions by studying different approaches, and to integrate them in his own special art of living. Not every life is a work of art, even if such potential is already there at the level of the most basic manifestation. Life becomes art in the hands of those human beings who choose to do justice to the complex thread they see and experience in the cosmic pattern wherein they are inscribed.

One of the bases of Daniélou’s approach to life (through Hinduism) is consideration of the six philosophical systems [darśana-s]as complementary perspectives in grasping reality. He was not interested in historical debates on Indian philosophy (where each system may appear in conflict with the others in order to affirm itself), but rather in what he had learned from the paṇḍit-s during the almost two decades he spent in Varāṇasī: how to apply a combination or practical synthesis of those systems in order to achieve his own awareness in tune with the complexity of the real: “many different relative truths can coexist without negating one another” (1), writes Daniélou, because for him ‘the real’ is a world of opposites in constant tension, in which human beings need to find a balance without reducing the dynamics of manifestation to a fixed dogma or preconceived idea (2). Because our faculties are limited, at every attempt to grasp the nature of reality, we stumble more than once upon the limit of the unknowable. In other words, knowledge can only be partial, and experienced truth cannot be other than manifold (and relative) (3). The difference between Daniélou and any post-modern thinker of today lies in the way this plurality is conceived and how it is integrated into a unifying background. According to Daniélou, rejection of religion (which characterizes the modern attitude toward reality) is absurd because it is simply a matter of assigning it its proper place within the scope of human life. The Hindu viewpoint considers religion a unifying factor encompassing a free plurality of research lines on the mystery of the real. According to Daniélou, this perspective is convincing merely because of the attitude it creates: respect and admiration for something we cannot fully understand, but in which we are embedded and can actively participate. “I have grown far too accustomed to an open and inquiring attitude toward all things […]and only feel comfortable with people who […]are completely without ready-made ideas or taboos”, he writes in his autobiography, and at the same time he declares, “the main purpose of religion is to provide men with a sense of the supernatural and an awareness of the divine nature of the world” (4). These judgements would appear contradictory in the eyes of a modern-trained European (since ideology is viewed as a dogmatic barrier to knowledge), but not in Daniélou’s eyes. For him religion is first and foremost an ‘intuition’ of nature as a living whole – natura generatrix, prakṛti or śakti – that precedes the ‘concept’ of nature as a profane world upheld by a sacred being beyond its reach. This intuition is an attitude to life found in the archaic religions of pre-Christian Europe and has been preserved in India for more than three thousand years. That is why Daniélou always tries to reconsider European antiquity in the light of Hindu thought (5) and integrate what is lacking in a Western world “so ignorant of the sources of its own culture” (6).

Daniélou’s outlook on life was in general terms that of a Hindu, that is, somebody who identified deeply with the type of knowledge transmission he received in a specific system of values (rituals, beliefs, myths and laws) in which he was also initiated [dīkṣā]in one of its major branches: Shaivism. However, the life-process is always much more complex than the living individual, and the ritual of initiation should not be confused with a path of spiritual enlightenment. What Daniélou embraced was Hinduism as a way of life, that is, according to the socio-cosmic framework of traditional Indian society and with special emphasis on a philosophical and artistic mode of existence. This is not the same as exclusively embracing saṃnyāsa, if we take the term to mean a radical form of asceticism attempting to surpass all human and natural limitations of the individual being and seeking liberation from saṃsāra. It suffices to read Daniélou’s book The Four Aims of Life (1992), which is a study of the double axis structuring Indian individual and social life: the doctrines of puruṣārtha-s (the four aims of social life: kāma, artha, dharma and mokṣa) and puruṣāśrama-s (the four stages of individual life: brahmacarya, gṛhastha, vanaprastha and saṃnyāsa), to realize that Daniélou’s integral vision of Hinduism as a system of values has no absolute, but a proportionate (and therefore limited) place for mokṣa and saṃnyāsa. In other words: he conceived absolute liberation from mundane chains as one of the paths followed by certain individuals (saints, yogis, mystics), but not as the highest ideal and only prescriptive aim of human life in general – as many Western ‘adepts’ of ashram-based Neo-Hindu movements nowadays do, even when they ignore almost all other aspects of Indian culture.

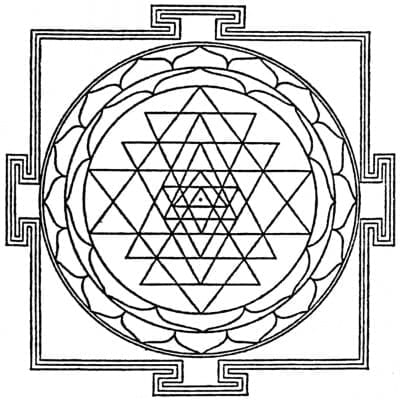

Srī Yantra, diagram with a special vibration of sound and light. Source: Alain Daniélou, Mantra: les principes du langage et de la musique selon la cosmologie hindoue, in: Cahiers d’Ethnomusicologie 4, 1991.

Srī Yantra, diagram with a special vibration of sound and light. Source: Alain Daniélou, Mantra: les principes du langage et de la musique selon la cosmologie hindoue, in: Cahiers d’Ethnomusicologie 4, 1991.Daniélou was quite convinced of the Hindu way of life as a commendable product of human culture, precisely because of the special attention that Hindu culture gives to the natural order of things – something that in his opinion prevents not only ecological disasters but also human alienation and existential crises. From a Western point of view this position represents a real problem, because in the West the basis of modernity goes hand-in-hand with a radical revision of the idea of ‘nature’ and ‘natural laws’, and modern social critique focuses rather on the problem of a ‘construction of nature’ or an ‘invention of eternal laws’ – a problem of a purely ideological nature that cannot be analyzed from a metaphysical and cosmological point of view. That is why his defence of the caturvarṇa system in India (that is, the distinction of four [catur]colorations [varṇa-s]in terms of status and function in society and its further division into clans or communities [jāti-s]) is a real scandal when judged by the standards of modern Western thought and has always been misunderstood. For Daniélou the caturvarṇa system is in the first place a millenary attempt to organize a society as close as possible to its natural function and holistic coherence (7). That is why the totalitarian idea of homogeneous identity is ruled out from the very beginning (8); the excesses of each group are regulated a priori by the organic dependence of the whole structure, and every expression of difference is accepted within the framework of local identities of different types. Although Daniélou recognizes that in the course of history this system has had its own problems (9), the main question for him remains how the coexistence of different human groups can be ensured in the long term (in the case of India more or less three millennia), and how diversity can be preserved in spite of the predatory nature of human beings. In this sense he was sceptical of the democratic experiment – especially after the end of traditional republicanism, the conjunction of liberal economy and shallow egalitarianism and the idea of exporting such new forms of democratic organization to non-Western cultures.

Social life is – beyond each specific cultural system – a dialectics of freedom and constraint, and it is within this dialectics that the individual should be placed. The fact that the individual does not come first in the organization of life has, for Daniélou, its metaphysical reasons. Any thought about the place of human beings in the cosmos has metaphysical implications, since it attempts to answer questions whose relevance lies beyond any empirical basis. The Western world has always seen in the human capacity to build a world of social structures, religious beliefs and political dynamics a qualitative difference with regard to any other form of life on earth. Daniélou did not feel comfortable with the idea that a species called homo sapiens, whose rise dates back to around 50,000 years ago (10) (an insignificantly short span of time on a cosmic scale), should be the centre of creation. The Purāṇic cosmologies helped him in his attempt to decentralise human beings from their privileged place as imago Dei or demiurge of history. Indeed, they show the insignificance of human life compared with broader, bigger and much more complex life-cycles, cycles of gods and Tradition (11). In his enigmatic book While the Gods Play (1987), Daniélou states that the time span of homo sapiens seems to correspond to the seventh human cycle [mahāyuga](12) and is inscribed in a much larger context of impersonal cosmic rhythms [kalpa, mahākalpa]. From the reduced perspective of human history, it seems that human beings have the powers of a divine creator, since they can alter (by means of seemingly complex acts of will) not only historical but also natural events. The cosmic point of view shows how narrow-minded this conception is, just by taking a look at the duration of a kalpa (or “day of Brahmā”, which corresponds to 4 yuga-s): 432,000,000 human years. The metaphor of the god falling asleep (at the end of his cosmic day) is a way of saying that the cycle comes to an end with the total absorption of everything that exists, a return to mūlaprakṛti, that is, to the non-manifested root of manifested nature. The illusion of the human will is to think that it can in some way have some sort of control over such cosmic patterns. For Daniélou, it means exactly the opposite: gaining awareness of the limited position of man within the complexity of the universe and understanding the process of creation as far as possible by fully reintegrating oneself in it. Re-integration is in this sense synonymous with de-centralization.

Two further aspects of Daniélou’s philosophical realism deserve to be mentioned. The first concerns his rejection of the doctrine of reincarnation and the second his deification of eroticism. Daniélou’s critical attitude toward the belief in reincarnation is based on two aspects related to reception of the karma conception within the framework of Indian asceticism: the deterministic morality that ensues from it, and the denial of every form of enhanced life as an ensnaring mechanism of ego-based ignorance. Within the horizon of dharmaśastra, such a critical attitude would make Daniélou a nāstika, that is, a heretic, somebody whose reasoning stands above the authority of tradition (13). It suffices to realize that belief in reincarnation is already established in the philosophy of the Upaniṣads, serving as the main support of the soteriological identification between ātman and brahman, and that the mechanics of saṁsāra as a bondage of perpetual death and rebirth depends very much on the logics of desire, that is, an irrational energy binding and driving human beings to different types of objects and thus preventing them from attaining the transcendent ground of all existence (14). Daniélou’s anti-ascetic attitude rescues the trans-personal aspect of desire (the cosmogonic and divine kāma) (15) and relates it to specific philosophical aspects of Shaivite saṃpradāya in which Tantric elements become ostensible. In his book The Hindu Temple (2001) he writes the following: “The uniting of the sexes is an expression of the nature of being that we envisage at a physical, mental, intellectual, subtle, or transcendent level. Upon reflection, it can reveal to us the secret of divine nature” (15). Life turns out to be a divine play, and human beings can be conscious participants in it. Enhanced awareness is also enhanced experience in every aspect of manifested reality: in the relationship with nature, animals and other human beings. There is no need to extend this awareness in time – both forwards and backwards – beyond individual existence and imagine a continuation beyond its concrete biological frame, since this extension is an abstraction and – on a social level – can be easily used for manipulation. The main thing is to realize the awareness of the all-encompassing cosmic thread in aesthetic pleasure, something which ultimately corresponds to religious and divine bliss. No wonder Daniélou explored dance, music, painting and writing as means to develop and express this awareness. His deification of eroticism is closely related to the way in which he cultivated the aesthetic sphere (through an expansion and an intensification of perception) as an approach to the divine: “Pleasure is not only the image but also the experience or realization of the divine […]. Only the voluptuousness of love, of pleasure, can give some idea of the divine bliss of which it is the reflection. Through this, we manage to get the taste of it and have the strength to renounce all our earthily ties” (17).

Such appreciations about sexuality and pleasure may shock the ordinary spiritual aspirant aiming at reaching mokṣa through renunciation of all worldly ties, but Daniélou’s view is never one-sided. In fact, he recognizes the metaphysical implications of the ties of Nature and he even uses the vocabulary of classical ascetic reformism in order to express the importance of the mokṣa-ideal within the Hindu tradition: “Whoever wishes to achieve liberation must conquer his or her own sexual nature, escape the flow of life, and interrupt the cycle of reincarnation. Nature and the gods, on the other hand, seek to keep human beings enslaved” (18). In this respect he resorts to the Tantric tradition and shows a very important aspect of the way human beings may deal with such enslavement. Sexuality (the strongest power of Nature) enslaves human beings only through their obsession with it, so that the most effective way of creating this obsession turns out to be a dissimulation of the thing itself: “Whatever dissimulates sexuality, whatever distinguishes it physically and morally – such as lying, modesty, and the notion of sin – are merely so many ways of dissimulating reality, so many weapons employed by nature to keep us more firmly in her nets” (19). In other words: Daniélou inverts the handed-down rules in order to achieve the same goal. This is a typical Tantric strategy, a principle of reversal (pratiloman = against the grain, or parāvṛtti = inversion) (20) introduced to render the search for liberation an expansive path, a path in which life is affirmed and embraced in its mysterious ambivalence and manifoldness, instead of being radically (and often pathologically) denied. If one takes a short step further, it is even possible to think of the reductive path of liberation as a constraint and replace it with a mode of living that is not so far from Nietzsche’s Dionysian world vision. After all, there is no possible eroticism without a background of vitalism.

Daniélou’s synthesis of hindu dharma is not only to be appreciated in his theoretical writings about it. In fact, theoretical appreciations are always one-sided, and theoreticians are obsessed with the reconstruction of a truth that is always partial and related to their own ego. The value of Daniélou’s work lies not only (and not mainly) in the perspective he developed out of long experience and study, a perspective he called “Shaivite” and defended against Christian, Muslim and even Brahmanic homogenization. It is rather to be seen in his own life, in his artistic work and in the heritage he bequeathed after his return to Europe. After all, what else is the Labyrinth at Zagarolo than a place in which human beings can be closer to nature, accepting its beauty and its violence without imposing any moral question, living in harmony with animals and plants and leaving aside any prejudice towards the behaviour of their neighbours? There is a whole ars vivendi in Daniélou that is still not as visible as it should be. Should we not regret this? Perhaps the greatest art, the highest expression of Daniélou’s spirit, is not to fully reveal the work in order to preserve it from the predators outside. Those who are part of the Labyrinth know that very well.

Notes:

(1) Alain Daniélou, The Way to the Labyrinth, New York 1987, p. 308.

(2) Cf. Alain Daniélou, Approche de l’hindouisme, Paris 2007, p. 21.

(3) Cf. Alain Daniélou, Ibidem., pp. 19-20.

(4) Alain Daniélou, The Way to the Labyrinth, p. 325.

(5) Alain Daniélou, Approche de l’hindouisme, p. 22.

(6) Alain Daniélou, The Way to the Labyrinth, p. 326.

(7) It suffices to take a look at the line running from the puruṣūkta of the Ṛgveda to Manusmṛti I, 87 to become aware of the importance of this system not only for the Hindu religion and social organization but also for the Indian imaginary, as well as the main representations of cosmic and human balance.

(8) “The natural recognition of racial and professional divisions, of the caste as natural basis of society, is probably the only remedy against nationalist excess and total war, the latter being a logical consequence of the former” (Alain Daniélou, La civilisation des différences, Paris 2003, p. 36.

(9) Alain Daniélou, Ibidem., p. 45.

(10) If we take into account the African ancestor of homo sapiens, who at that time seems to have migrated to the Middle-East and Asia. This is the line Daniélou followed in his research of cosmic cycles, since he speaks of the appearance of Cro-Magnon in 58,042 BCE

(11) Cf. Alain Daniélou, Viṣṇu the Pervader, in: Adyar Library Bulletin (New Series), Vol. XVIII, part 3-4, December 1954, pp. 336-380, especially p. 340.

(12) That is, a cycle of four yuga-s: kṛta yuga (age of accomplishment), tretā yuga (age of the three ritual fires), dvāpara yuga (age of doubt) and kali yuga (age of conflict), cf. Alain Daniélou, While the Gods Play, Rochester: Vermont 1987, p. 198.

(13) Cf. in this respect Manusmṛti II, 8, where the positive authority of revelation [śrutiprāmānya]is clearly placed beyond the eye of knowledge [jñānacakṣu].

(14) Cf. Bṛhadāraṇyaka Up. III, 8, where the only real satisfaction of desire lies in freedom from all desire as a condition for the possibility of the identification of the personal self [ātman]with the ultimate and absolute reality [brahman].

(15) It is not surprising that Daniélou quotes among other sources the Vedic cosmogonic myth reproduced in the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad (I, 4.3) in order to emphasize exactly the opposite of what is highlighted by ascetic soteriology.

(16) Alain Daniélou, The Hindu Temple: Deification of Eroticism, Rochester: Vermont 2001, p. 8.

(17) Alain Daniélou, Ibidem., p. 103.

(18) Alain Daniélou, Ibidem., p. 116.

(19) Alain Daniélou, Ibidem.

(20) Cf. Georg Feuerstein, Tantra: The Path of Ecstasy, Boston: Massachussets 1998, p. 8.