Index

- » Letter from the Honorary President Jacques Cloarec

- » Alain Daniélou’s Philosophical Realism: A lesson in Ars Vivendi, Adrián Navigante

- » Swāmī Karpātrī: The Nation’s Development and Dharma, Himadri Ketu

- » From Spectator to Dancer, Aleksandra Wenta

- » On the Subtle Body in Neoplatonism, Felix Herkert

- » A Talk with Alain Daniélou: Shiva-Dionysos Among Us

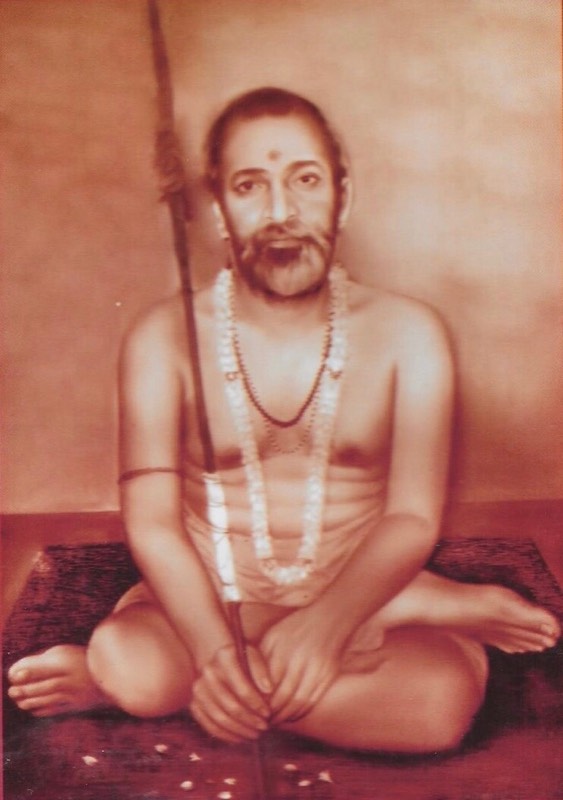

Swāmī Karpātrī: The Nation’s Development and Dharma

Translation from the Hindi and introduction by Himadri Ketu Sanyal (Alain Daniélou Foundation grantee)

Introduction

Swāmī Karpātrī (1907-1982) was an unusual figure in Indian thought who, while leading the life of a sannyasin, didn’t quite renounce the world, but rather took an active part in it for different purposes of social and cultural relevance to his country (1). In the following translation of his text- राष्ट्रोन्नति और धर्म (2), (The Nation’s Development and Dharma), his position in the wake of Indian nationalism comes to the fore, especially his vision of an independent Indian nation and the role that dharma should play in it.

Karpātrī propounded a particular vision of India which corresponded neither to the dichotomy capitalism/communism nor to that of contemporary (liberal) democracy. Instead, he stressed the need to base the independent Indian nation on the traditional ideal of dharma, as it appears in Vedic tradition. According to Karpātrī, communism and capitalism are political systems inevitably driven by greed and force. Instead of following either of these systems, Karpātrī emphasized the duties and aims of the individual from the perspective of the famous doctrine of the puruṣārthas (3): kāma, artha, dharma and mokṣa. This doctrine states that a human being should first aim at fulfilling the duties of the external world before seeking liberation from mundane existence, meaning that social duty plays a central role, and in this sense, is a harmonious and thoroughly regulated collective instance that alone can guarantee the people’s happiness and establish harmony in their lives.

In the following text, presented in the original Hindi with an English translation, Karpātrī explains various kinds of dharmas, especially rājadharma (king’s duty), and svadharma (duties of an individual) with references and examples drawn from the Epic tradition (Mahābhārata and Rāmāyaṇa) to state the importance of dharma for both individual and society and stress its contribution to the welfare of both.

With Swāmī Karpātrī, we are confronted with a line of thought that at the time of the struggle for Indian Independence constituted an alternative position with regard to modern democratic reformism (clearly a European import) and to the nationalist option also based on modern (Western) political regimes. We also find a doctrinary emphasis on ethical aspects of Indian social life that traditional thought considered central to the establishment of social order. In this sense, the immediate context of his social and political interventions as well as the pedagogical character of his writings should not obscure the problematic behind them, which is ultimately the coexistence of a traditional position in the real political arena with other trends that seem exclusively to characterize social life in modern India. As difficult as it may appear to link politics with dharma in the context of modern political institutions, Swāmī Karpātrī saw a need to emphasize that link as the sole remedy for the otherwise inevitable decadence of institutional life.

राष्ट्रोन्नति और धर्म

बिना धार्मिक भावनाओं का प्रतिष्ठापन हुए सुखपूर्वक समाज एवं राष्ट्र का सुसंघटन हो ही नहीं सकता। सुन्दर स्त्री, रत्न तथा राज्यादिविहीन दूसरों की उक्त सुख सामग्रियों को देखकर स्पृहा या ईर्ष्या करते हैं। कोई क्यों साम्राज्यादि सुख-सामग्री-संपन्न और हम क्यों दरिद्र एवं दुःखी रहे? बस, एतन्मूलक राजा-प्रजा, किसान-जमींदार और पूँजीपति-मजदूरों का संघर्ष होना स्वाभाविक है। एक ओर ईर्ष्या या रागवश मजदुर, किसान संघटन करते हैं और क्रांति पैदा करके पूँजीपति, जमींदार आदि को मिटा देना चाहते हैं। दूसरी ओर राजा तथा धनींमानियों को भी प्रमादवश गरीबों का शोषण करके अपनी ही भोगसामग्रियों में सर्वस्व लगाने की सूझती है। एक वर्ग कुछ नहीं देना चाहता, दूसरा सब कुछ ले लेना चाहता है। इस तरह धन एवं भोग में आसक्त धनिकवर्ग दरिद्रता, उत्पीड़न एवं ईर्ष्या से पीड़ित निर्धनवर्ग अपने-अपने कर्तव्यों से वंचित होकर राष्ट्र और समाज के जीवन को संकटपूर्ण बना देते हैं। शास्त्र एवं धर्म एक ऐसी वस्तु है, जिससे सभी में संतोष एवं सामंजस्य की भावना प्रतिष्ठित होती है। शास्त्र और धर्म का प्रभाव ऐसा था कि लोग पर-स्त्री एवं पर द्रव्य को विष के समान मानते थे। लोगों की यह धारणा थी कि सम्पन्ति-विपत्ति, सुख-दुःख में अपने शुभाशुभ कर्म ही मुख्य हेतु है। क्यों हम दुःखी एवं दरिद्र हुये, इसका समाधान वे इस तरह कर लेते थे कि जैसे अपने कर्मवश कोई पशु, कोई पक्षी, कोई अंध बधिर या उन्मत होता है, वैसे ही कर्मों के अनुसार ही कोई भोग-सामग्री से विहीन और कोई उससे सम्पन्न होता है। प्राणी को अपने शुभाशुभ कर्मों के अनुसार सुख-दुःख, सम्पन्ति-विपत्ति भोगनी पड़ती है। उसे अपनी ही सम्पन्ति तथा सुख-सामग्री में सन्तुष्ट रहना चाहिये। परकीय धन या कलत्र की स्पृहा न करनी चाहिए। पुरुषार्थ से अपने आप हृष्ट-पुष्ट हो जाना और बात है, दूसरों की हृष्टित पुष्टता मिटाकर अपने समान उसे भी बना देना और बात है। ऐसे ही अपने सत्यप्रयत्नो से सुन्दर भोग-सामग्री सम्पादन करना यद्यपि युक्त ही है, तथापि दूसरों की सामग्रियों से ईर्ष्या करना, उसे अपहरण करना अवश्य ही पाप है। ऋषिलोग अरण्यों में रहते थे और नदियों के तट पर कुद्दाल आदि में कुछ सामग्री उत्पन्न करते थे। उसमें से भी वे राजा का अंश निकालकर उसकी इच्छा ना होते हुए भी उसे दे आते थे। पाप बन जाने पर पापी स्वयं जाकर राजा से दंड ग्रहण करते और उससे अपनी शुद्धि समझते थे। अब भी पाप बन जाने से अपने आप पापों के प्रायश्चित करने की प्रथा भारत में कुछ प्रचलित है। लिखित महर्षि ने अपने भाई शंख के ही उद्यान से फल लेने को चोरी समझा और शुद्ध होने लिए राजा के वहाँ स्वयं जाकर राजा की अनिच्छा रहते हुए भी हस्तच्छेदन कराया। इस तरह जब अपनी न्यायोपार्जित सामग्रियों में सन्तुष्ट रहने का अभ्यास था, परकीय या अन्याय-समागत वस्तुओं से घृणा एवं भय था, परोपकार करने में पुण्यवृद्धि एवं उत्सुकता तथा पर-पीड़न में घृणा और उद्वेग होता था, तब समाज तथा राष्ट्र की व्यवस्था स्वाभाविक ही थी। मिलने पर भी सभी भरसक यही प्रयत्न करते थे कि दूसरे की वस्तु न ली जाय। इसके विपरीत देने वालों को यही स्पृहा रहती थी कि किस प्रकार अपनी वस्तु परोपकार में लगे। घर-घर आतिथ्यसत्कार की प्रथा थी। वैश्वदेव के उपरांत द्वार पर खड़े होकर अतिथि पाने की प्रतीक्षा की जाती थी। उसके न मिलने पर खेद प्रकट किया जाता था। अग्निहोत्र में अग्नि भगवान् से अतिथि पाने की प्रार्थना की जाती है। क्या ही उदात्त भावना थी। बहुत उपवासों के बाद श्रीरन्तिदेव वैश्वदेवादि कृत्य करके थोड़ासा सत्तू खाने बैठे, तब पुल्कस आदि कई अतिथि आ पहुँचे। रंतिदेव सब कुछ उन्हें देकर जलपान करने लगे। इतने में ही एक श्वपच अपने कुत्तों के साथ आ पहुँचा और उसने अपनी क्षुधा पिपासा की व्यथा सुनायी। श्रिरन्तिदेव समस्त जलप्रदान करके भगवान से प्रार्थना करने लगे कि हे, नाथ ! मैं स्वर्ग-अपवगर्द आदि कुछ भी नहीं चाहता हूँ केवल यही कि संतप्त, आर्त प्राणियों का कष्ट मुझे मिल जाय और सभी प्राणी सुखी हो जाँय-

न त्वहं कामये राज्यं न स्वर्गं नापुनर्भवम्।

कामये दुःखतप्तानां प्राणिनामार्तिनाशनम्।।

यज्ञ-यागादि के व्याज से सभी सम्पत्तिशाली अपनी सम्पत्तियों का विभाग करके समता उत्पन्न कर देते थे । राम के यज्ञ में महाभागा वैदेही के हाथ में केवल सौमंगल्य सूत्र ही अविशिष्ट रह गया ।यद्यपि वह समय सम्राज्यवाद का था, तथापि वर्तमान जनतंत्र या साम्यवाद उस शासन के सौन्दर्य की बराबरी कथमपि नहीं कर सकते। राजा अपने भुजबल से साम्राज्यपालन करते थे, उनका राष्ट्र निज भुजबल पर सुरक्षित था, सेना शोभा के लिए थी। उसके शैथिल्य होने पर सम्राट स्वतः युद्ध भूमि में अवतीर्ण होते थे, फिर भी बिना प्रजा के अनुमति के पुत्र तक को शासन भार नहीं दिया जा सकता था। प्रजा के लिए सम्राट अपने पुत्र, पत्नी तक का परित्याग कर सकते थे। सूर्य जैसे तिग्मरश्मियों से पृथ्वी का रस ग्रहण करते हैं और वर्षाऋतु में उसे भूमि को प्रदान कर देते हैं, वैसे ही प्रजा से कर तो लिया जाता था, परंतु उनका लक्ष्य केवल प्रजा का संरक्षण ही था।

परलोक में अभीष्ट फलप्रदान करने वाले संध्या, जपादि धर्म का अनुष्ठान तथा अनिष्टप्रद सुरापान और अमृत-परिवर्जन तो नास्तिकों को भी करना चाहिए। फल के संदेह में भी कृषि, व्यापारादि कार्य किये ही जाते हैं। इसी तरह परलोक के संदेह में भी धर्म करना ही चाहिए यदि परलोक में धर्म की अपेक्षा हुई, तब तो धर्म न करने वाला पछतायेगा तथा करनेवाला आनन्दित होगा और धर्म की कुछ अपेक्षा न हुई, तो भी करनेवाले को कोई हानि नहीं। फिर किसी दूर जंगली प्रदेश में जाना हो, तो भोजन-सामग्री और रक्षा के साधन शास्त्र-अस्त्रादि से सुसज्जित होकर ही जाना चाहिए। यदि वहाँ व्याघ्रादि का आक्रमण हुआ, तो वे काम आयेंगे, नहीं तो पछताकर प्राण गवाना पड़ेगा। परंतु सामग्री रहने पर यदि आवश्यकता न भी हुई, तो भी कोई हानि नहीं। अनादि काल से आस्तिक-नास्तिक का शस्त्राथ चलता है, कभी नास्तिकों का और कभी आस्तिकों का पराजय होता है। कोई भी मत अत्यंत खण्डित या मण्डित नहीं हो सकता। सर्वत्र ही पराजय होने पर भी मति का ही दौर्बल्य समझ जाता है, न कि मत का। इसलिए समझदार नास्तिक को भी परमेश्वर और धर्म के विषय में संदेह तो हो ही सकता है, परन्तु ऐसे भी बहिर्मुख देश तथा समाज हैं, जहाँ परमेश्वर और धर्म की चर्चा तक नहीं, फिर संदेह कहाँ से हो सकता है ? संदेह से जिज्ञासा और जिज्ञासा से बोध भी अनिवार्य होता है। अतः ईश्वर और धर्म में संदेह तक अतिदुर्लभ है। इसलिए संदेह हो तो भी नास्तिकों को धर्म का अनुष्ठान करना परमावश्यक है।

कुछ लोग कहते हैं कि शास्त्रों एवं तदुत्त धर्मों को मानने वालों में कष्ट ही दिखाई देता है, शास्त्र न मानना ही श्रेष्ठ है। परंतु यह ठीक नहीं, जहाँ शास्त्र न मानने वालों की संख्या अधिक है, वहाँ शास्त्र मानने वालों को कष्ट है और जहाँ शास्त्र मानने वालों की संख्या अधिक है, वहाँ उसके न माननेवालों को भी दुःख है। परंतु बुद्धिमानों को तो यह सुनिश्चित है कि यथेष्ट चेष्टावाले बानर की अपेक्षा नर में यही विशेषता है कि वह शास्त्र मानता है और शास्त्रानुसार व्यवहार करता है। प्रमाणभूत शास्त्र के बिना जैसे लोग सुख के भाजन नहीं होते, वैसे ही प्रमाणभूत शास्त्र के बिना भी प्राणियों को सुख नहीं होता। कहा जाता है कि लोक में तो विपरीत ही देखने में आता है। सशास्त्र दुःखी और अशास्त्र सुखी है। परंतु यह बात बिना विचार से ही है। तृप्ति को ही सुख कहा जाता है, पशुओं में भोजन से और मनुष्यों में ज्ञान से तृप्ति होती है। ज्ञान शास्त्र से होता है। क्या ज्ञान सुख का प्रतिबंधक है ? कौन सा ऐसा सुखपात्र है जो प्रमाणविहीन हो? आरण्यक पशुओं को भी तो सुख के लिए क्षोत्र, चक्षु आदि प्रमाणों की अपेक्षा है, उनके वैगुण्य में वे भी दुःखी ही होते हैं। मनुष्य की यह विशेषता है कि उसमें पशुसाधारण प्रत्यक्ष तथा अनुमान प्रमाण है, साथ ही शास्त्रप्रमाण अधिक है। जैसे राजा का आश्रय लेकर निर्बल प्राणी भी प्रबल से प्रबल को जीत लेता है, वैसे ही धर्म और न्याय के सहारे प्राणी सम्राट को दबा सकता है। महास्वतन्त्र निजभुजबल से विश्वविजेता धर्म के ही भय से आत्मनियंत्रण करता है। खड्गादि अस्त्र-शस्त्र संपन्न करोड़ों शूरवीर निःशस्त्र स्वामी के भी अधिक्षेपों को सहते हैं। प्रधान कारण यहाँ स्वामिद्रोह का भय ही है। कहीं-कहीं अधर्म के प्राबल्य में भी प्राणी को अनंत साम्राज्य, समृद्धि तथा वैभव देखा जाता है। परंतु वहाँ पूर्व जन्म का ही धर्म और तप मूल समझना चाहिए। रावण का अद्भुत्त वैभव देखकर श्रीहनुमान जी ने कहा था कि यदि अधर्म बलवान न होता, तब तो यह रावण शक्र्सहित सुरलोक का शासक होता-

यद्यधर्मों न बलवान् स्यादयं राक्षसेश्वरः।

स्यादयं सुरलोकस्य सशक्रस्यापि रक्षिता।।

दूसरे प्रसंग में रावण से ही श्रीहनुमान जी ने कहा था कि ‘हे रावण ! पूर्व सुकृतों का फल तुमने पा लिया, अब अधर्म का भी फल शीघ्र ही पाओगे’-

प्राप्तं धर्मफलं तावत् भवता नात्र संशयः।

फलमस्याप्यधर्मस्य क्षिप्रमेव प्रपत्स्यसे।।

इसलिए सिद्धान्त यही होना चाहिए कि जो कर्म धर्म से विरुद्ध हो उससे चाहे कितना भी बड़ा फल क्यों ना हो, बुद्धिमान पुरुष उसका सेवन कदापि करें-

धर्मादपेतं यत्कर्म यद्यपि स्यान्महाफलम्।

न तत्सेवेत मेधावी न हि तद्धितमुच्यते।।

धर्म से विद्या, रूप, धन, शौर्य, कुलीनता, आरोग्य, राज्य, स्वर्ग-मोक्ष सब कुछ मिलता है-

विद्या रूपं धनं शौर्यं कुलीनत्वमरोगता।

राज्यं स्वर्गश्च मोक्षश्च सर्वं धर्मादवाप्यते।।

ऐसे धर्म को छोड़कर क्या कोई राष्ट्र उन्नति कर सकता है?

English Translation

It is not possible to form a harmonious society and nation without establishing dharma (4) in it. Without beautiful women, gems and kingdoms, etc., a man becomes covetous or envious of such possessions belonging to others. Why should somebody else be well off with all the assets of comfort, kingdoms, etc. and why should we remain poor and miserable? It is only natural therefore that conflicts arise between a king and his subjects, between farmers and landowners, capitalists and workers. On the one hand, out of envy and zeal, workers and farmers organize themselves and through revolution they seek to annihilate capitalists, landlords and so on. On the other hand, the king and affluent people engage entirely in material enjoyment through the insane exploitation of the poor. One class does not want to cede anything and the other wants to take everything. Thus, the rich class, indulging in riches and material luxuries, and the poor class stricken with poverty, oppression and envy repudiate their duties, thereby threatening the harmony of the society and nation. Śāstra (5) and dharma are what induces the spirit of contentment and harmony among people. Śāstra and dharma once had such an effect that people considered others’ women and wealth as evil. People had this belief that our own good and evil deeds, i.e. karma (6), were our only chief aid in times of prosperity or poverty, or in times of welfare or hardship. The cause of grief and poverty was once understood as determined by karma, for example being born as an animal or a bird or being blind, deaf or insane, was all believed to be determined by karma, and similarly karma was understood to be the cause of people’s poverty or prosperity. All living beings experience joy and grief, prosperity and hardship only according to their karma. A man should be content with his own assets and material possessions. He should not covet others’ riches and women. It is one thing to prosper by one’s own efforts and another to deprive somebody of his possessions and make him like oneself. Therefore, although it is appropriate to generate fine material wealth from one’s own noble endeavours, it is nevertheless always a sin to envy others’ possessions and steal them. The sages used to live in the jungles and would produce goods with the help of a spade on the banks of rivers. From that produce they would give part to the king, even against the wishes of the king. Having committed a crime, the culprit used to go to the king himself to receive punishment and considered it as a purification of himself. The practice of atoning for one’s sins oneself is still somewhat prevalent in Bhārata (7). The great sage Likhit (8) regarded taking fruit from his own brother Shankh’s garden as an act of stealing and for his self-purification he went to the king and got his hands chopped off against the king’s wish. Thus, when the practice prevailed of being content with one’s own rightfully earned things, people used to resent and even fear the unjust acquisition of others’ property; charity was performed eagerly and was seen as virtuous, whereas atrocities against others were despicable and dreadful; all this resulted in the natural order of society and the nation. Even when offered, people tried their best not to take others’ goods. At the same time, the wealthy eagerly desired to offer their goods for others’ welfare in every way. Hospitality was a tradition in every household. After the Vaishwadeva (9) ceremony, a man would wait at the gate to receive guests. He would be remorseful if no guests came. The god Agni (10) is prayed to at the fire altar in order to receive guests as a blessing. What a noble sentiment that was! When after a long fast Srirantideva (11) sat to eat some roasted gram flour after making an offering to Vaishwadeva, members of the Pulkaśas caste then arrived (12). Rantideva offered them everything and himself started drinking water. At that moment came a Shwapac (13) with his dogs and told Rantideva his grief for hunger and thirst. Srirantideva gave all his water to him and began to pray to god: O Lord! I do not crave for heaven or mokṣa (14), etc., but I only wish to take on myself the sufferings of agonized and distressed beings so that everybody may be blessed with joy-

न त्वहं कामये राज्यं न स्वर्गं नापुनर्भवम्।

कामये दुःखतप्तानां प्राणिनामार्तिनाशनम्।।

By the virtue of oblations and sacrifices, wealthy people used to divide their wealth and create parity. In her oblation for the lord Rama (15) the very prosperous Vaidehi (16) had only the very auspicious thread left in her hands. Although that was the time of Sāmrājyavad (17), the current form of governance, democracy or communism, cannot in any way match the beauty of that governance at all. The king would run the empire by his own prowess, the nation’s safety was granted by his prowess alone and the army was but an embellishment. When the army became weary, the emperor himself would appear on the battlefield, but his son would not however be allowed to rule the kingdom without the people’s permission. The emperor might abandon his son, even his wife, in order to serve his people. Just as the sun receives earth’s water through its rays, and gives it back during the rainy season, similarly tax was collected from the people, but its only reason was to provide protection for them.

Even atheists should say evening prayers, chant mantras, perform dharma-rites, drink terrible potions and abstain from sweet nectar in order to receive the desired result in the next world, or heaven. Despite the uncertainty of the end result, farming, business, etc., goes ahead. Similarly, even when doubtful about the existence of the other world, a man should attend to his dharma, so that if dharma is expected in the next world, then the man who has not done his dharma rites will regret it and the one who has performed his dharma rites will be exhilarated; and if dharma is not expected, then still no harm is done to dharma believers. When a man has to go to a faraway wild land, he should go provided with adequate food supplies, and means and weapons for protection. If tigers invade, then such equipment will be of use, otherwise he will have to die, unfortunately. But even if the weapons carried are not used, there is no loss. From time immemorial, there has been debate between theists and atheists, leading sometimes to the defeat of the atheists and sometimes of the theists. No argument can be completely deficient or completely defensive. Even after being defeated everywhere, it is the argument that is considered weak, not the faith. Therefore a wise atheist can have doubts concerning the subjects of god and dharma, but there are also liberal countries and societies where there is no debate about god and dharma, and therefore, how is it possible to have room for doubt? Doubt leads to curiosity and curiosity certainly leads to knowledge. Hence, even doubt in god and dharma is very rare. So even in the case of doubt, it is important for atheists to perform the rites of dharma.

Some say that only suffering appears on the path following the śāstras and the dharmas mentioned therein, so it is best not to follow the śāstras. But this is not right: where large numbers of non-believers live, not following the śāstras causes trouble to śāstra-believers, whereas when there is a large number of śāstra-believers, there it becomes troublesome for non-believers in the śāstras. But the wise man definitely knows that it is an attribute of human beings as compared to the bountiful attempts of an ape that he can follow the śāstras and behave accordingly. Indeed, without the authoritative śāstras people will not even know contentment, and so, without the authoritative śāstras, it is not possible to achieve contentment. It is said that the opposite is witnessed in this world: śāstra-believers are miserable and non-believers are prosperous. But this opinion is formed without contemplation. Contentment is the only true joy: animals achieve it by means of food and human beings through wisdom. The śāstras are the origins of wisdom. Does wisdom restrict contentment? Is it possible to achieve contentment without any evidence? Even wild animals have ears, eyes, etc. as evidence for achieving contentment, and in their deprivation they also grieve. It is a characteristic of human beings that they possess ordinary animal perceptions and thinking capabilities, but also have the testimony of the śāstras. For example, a weak man can overpower a more powerful one with the help of the king, likewise with the help of dharma and nyaya (Justice), one can even overcome the emperor. The great winner who can beat the world solely by his own prowess achieves self-control only from fear of dharma. Millions of knights laced in armour and weapons bear the scorn of their weaponless masters. The main reason is that they fear to protest against their masters. Sometimes we also witness endless empire, prosperity and wealth under the domination of adharma (18). But that should be regarded as the result of good deeds or dharma in a previous birth. Seeing the wonderful splendour of Rāvaṇa (19), Srihanumanji (20) said that if adharma had been powerful, then Ravana would have been the ruler of heaven with his Rakshshas (Demons)-

यद्यधर्मों न बलवान् स्यादयं राक्षसेश्वरः।

स्यादयं सुरलोकस्य सशक्रस्यापि रक्षिता।।

In another context Srihanumanji said to Ravana, ‘O Ravana! You have attained the fruit of former good deeds and now soon you will get the fruit of your adharma’.

प्राप्तं धर्मफलं तावत् भवता नात्र संशयः।

फलमस्याप्यधर्मस्य क्षिप्रमेव प्रपत्स्यसे।।

The principle must therefore be that whatever the act against dharma, no matter how much greater its fruit may be, wise men should always avoid it-

धर्मादपेतं यत्कर्म यद्यपि स्यान्महाफलम्।

न तत्सेवेत मेधावी न हि तद्धितमुच्यते। ।

From dharma one gains everything: wisdom, beautiful appearance, chivalry, nobility, health, estates, heaven and mokṣa-

विद्या रूपं धनं शौर्यं कुलीनत्वमरोगता।

राज्यं स्वर्गश्च मोक्षश्च सर्वं धर्मादवाप्यते।I

Is it possible for any nation to develop without such dharma?

Notes:

(1) He established Dharma Sangha in 1940, a cultural association for the defence of traditional Hinduism against modern trends and, in 1941, a daily paper Sanmarg in Varanasi. Within the context of a newly independent India struggling to find its identity, he founded the political party Ram Rajya Parishad in 1948, a traditionalist Hindu party in which he brought politics and religion to a single platform for the welfare of the people. He published more than twenty works dealing with relations between politics and religion, most of which have not so far been translated.

(2) The text is taken from the book Saṃgharṣa aur Śānti (Vārāṇasī 2001, 4th Edition) (Struggle and Peace), a compilation of articles by Karpātrī, previously published in the daily paper Sanmarg or the periodical Siddhanta.

(3) Puruṣa means “person” or “man,” and artha means “aim” or “goal” or “purpose”, in addition to the narrower meaning of “means” or “wealth” (Koller 1968, 315). The four main human aims or puruṣārthas are dharma, artha, kāma and mokṣa.

(4) The term dharma is essentially untranslatable in any language, as it presents a very complex set of meanings and English words such as religion, law, morality or goodness cannot convey the deep meaning which this term has acquired during the development of Hindu thought (Suda 1970, 359). The word etymologically comes from the root dhr-, “to sustain” or “to uphold” (Klostermaier 1989, 47). Klaus K. Klostermaier explains that dharma has its roots in the structure of the cosmos, and encompasses the socioethical laws of humanity as well as prescribing functions and duties to the separate classes of society to maintain harmony and well-being in that society (ib., 47-50). In the Upanishads, dharma manifests itself as a supreme power, as a “Force of Forces” and “Power of Powers”(Rao 2007, 106).

(5) The vast corpus of wisdom in Hinduism has its origin in the Vedas (Singh 2001: 100). The earliest record of Indian thought and culture is found in the Vedas, the scripture of Hinduism, which is not a single book but comprises a vast literature. The scriptures that illustrate the social aspect of dharma are: Nitiśāstra, Ayurveda, Rasayanśāstra, Gandharvaśāstra, Sangeet, Kaamśāstra (sciences of ethics, medicine, chemicals, musical subject matter, music, sex).

(6) The doctrine of karma and rebirth has been given great importance in the various Indian religious traditions (Hindu, Buddhist, Jain) and Karpātrī explains, with the help of karma theory, all the suffering that results from every individual’s wrongdoing, whether in this or in a previous life; all wrongdoing in this present life will be punished in either this or a future life. The author Whitley R. P. Kaufman argues in his article Karma, Rebirth and the Problem of Evil (2005) that the doctrine of karma and rebirth works like a theory of causation and provides Indian religion with a more emotionally and intellectually satisfying account of evil and suffering.

(7) Another official name of India, derived from the ancient Hindu Puranas.

(8) The story of the brothers Likhit and Shankh is told by Vyasa to Yudhiṣṭhira in the Mahābhārata to highlight the importance of punishment (daṇḍa). King Sudyumna had to take the harsh decision of chopping off the hands of sage Likhit as punishment for taking fruits from his brother’s garden without his permission. Karpātrī shows by this example that daṇḍa, along with dharma was also necessary to maintain order in society, but more important was self-acknowledgement that one has committed a mistake and deserves punishment for purification.

(9) Vaishwadeva is a Vedic ceremony, at which cooked food is first offered to gods through the sacred fire and then an unknown guest is invited to the house to partake of it; only later does the householder eat the remnants. In section XCVII of the Mahābhārata, Bhishma explains to Yuddhisthira the importance of this ceremony for a householder.

(10) Vedic fire god.

(11) Srirantidev, a very generous king, fasted for 48 days in order to save his kingdom and people from famine, and when he sat down to break his fast, there arrived members of low castes to whom the king gave his food and water and prayed to god to give him all the sufferings of these people.

(12) Besides the usual four castes, there are also certain outcastes, such as the Chaṇḍālas, Pulkaśas and slaves (Viswanatha 2000, 128).

(13) Member of an outcaste who light the fire to burn corpses at the crematorium.

(14) Mokṣa is seen as the ultimate spiritual aim, the other three being dharma, artha and kāma, interpreted as material aims of life.

(15) The seventh avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu.

(16) Another name of the goddess Sita.

(17) Reference to Ramrajya, Kingdom of Rama. The king’s rule of his kingdom is called rājadharma. In Karpātrī’s text, although Ramrajya is perceived as the most ideal society, where the king’s duty, rājadharma was devoted only to the welfare of his people, the power to choose the king, or to overthrow him, is given to the people. Dharma is the main regulatory force in society and it comes before the king.

(18) Opposite of dharma.

(19) Prime antagonist in the Hindu epic Rāmāyaṇa.

(20) Devotee of the Lord Rama.

Selected bibliography of works consulted for the introduction and footnotes:

Primary Sources:

– Karpātrī, Swāmī (2001): Saṃgharṣa aur Śānti. Vārāṇasī, Shree Karpātrī Dham.

– Karpātrī, Swāmī (2013): Rashtriye Swayam Sewak Sangh and Hindu Dharma. Vārāṇasī, – Shree Karpātrī Dham.

Secondary Sources:

– Creel, Austin B. (1975): “The Reexamination of “Dharma” in Hindu Ethics”. In: Philosophy East and West, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 161-173.

– Dandekar, R.N. (2000): “Vedic Literature: A Quick Overview”. In: Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Vol. 81, No. 1/4, pp 1-13.

– Daniélou, Alain (1987): The Way to the Labyrinth: Memories of East and West. New York: New Directions Book.

– Kaufman, Whitley R. P. (2005): “Karma, Rebirth, and the Problem of Evil”. In: Philosophy East and West, Vol. 55, No. 1, pp. 15-32.

– Klostermaier, Klaus K. (1990): A Survey of Hinduism. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, New Delhi.

– Koller, John M. (1972): “Dharma: An Expression of Universal Order”. In: Philosophy East and West, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 131-144.

– Koller, John M. (1968): “Puruṣārthas as Human Aims”. In: Philosophy East and West, Vol. 18, No. 4, pp. 315-319.

– Jaffrelot, Christophe (1993): “Hindu Nationalism: Strategic Syncretism in Ideology Building”. In: Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 28, No. 12/13, pp. 517-524.

– Meena, Sohan Lal (2005): “Relationship between State and Dharma in Manusmriti”. In: The Indian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 66, No. 3, pp. 575-588.

– Radhakrishnan, S. (1922): “The Hindu Dharma”. In: International Journal of Ethics, Vol. 33, No. 1, pp. 1-22.

– Rao, K. Sreeranjani Subba (2007): “Vedic Ideals and Indian Political Thought”. In: The Indian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 68, No. 1, pp. 105-114.

– Singh, Karan (2001): “Some Thoughts on Vedanta”. In: India International Centre Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 3, pp. 100-108.

– Suda, J. P. (1970): “Dharma: Its Nature and Role in Ancient India”. In: The Indian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 31, No. 4, pp. 356-366.