” The first duty of man is to understand his own nature and the basic elements of his being,

which he must fulfill to the best of his ability “

Alain Daniélou

Index:

- » Letter from the Honorary President Jacques Cloarec

- » Yoga and Religion: on Alain Daniélou’s “Method of Re-Integration”, Adrián Navigante

- » Around Our Corner, Samuel Buchoul

- » Shiva in the Work of Alain Daniélou: Archetype and Reference Figure, Anne Prunet

- » Alain Daniélou: The Connection of Ragas with the Hours of the Day and the Seasons

- » Whispers in the Labyrinth, Shuddhabrata Sengupta

Letter from the Honorary President Jacques Cloarec

Dear Friends,

Once again the year is coming to an end. For those who share Alain Daniélou’s view of nature and the world, it is evident that, with the end of a cycle, a new one begins. Time is linked to natural rhythms, and from that point of view it has no beginning and no end. It contains a central element of change and two mutually interacting poles: exhaustion and renewal. Human activity adds a prism of nuances and very important patterns of creativity to the dynamics of creation.

On the occasion of the New Year, the Alain Daniélou Foundation is happy to transmit signs of renewal for next year related to our activities and projects.

Firstly, the whole the Alain Daniélou Foundation team is untiringly at work on restructuring our website: the results will be seen at the end of January with the launching of the Alain Daniélou Foundation’s new webpage. Although the transfer of existing contents will take some time, we will very soon have a new virtual window on the world in order to communicate our activities, projects and events in quite another way – hopefully a very exciting one for our readers, as well as internet surfers.

Secondly, in two years’ time the Alain Daniélou Foundation Artistic Dialogue will host an international conference on microtonality, the history and the development of which is closely related to Indian music and Alain Daniélou (who developed a complex theory of music intervals with transdisciplinary results). This event promises to be transcendental on many levels: complexity, theory, the practice of music and repercussion on fields other than musicology. Most of the decisive preparatory work will be carried out in France, Italy and Germany during the course of 2016.

Thirdly, on the part of the Alain Daniélou Foundation Intellectual Dialogue, important interactions are announced with the C. G. Jung Institute in Switzerland and the University of Freiburg in Germany. Following the spirit of Alain Daniélou, the Alain Daniélou Foundation Intellectual Dialogue is working on new perspectives to bring Europeans and Indians together and gain a deeper experience of the dynamics of their interaction. Within this context Alain Daniélou’s work will be the subject of new publications both in English and in German.

Last but not least, Alain Daniélou’s thought will be relaunched through the publication of e-books, since this virtual means can reach many readers in no time, far beyond the possibilities of ordinary publications.

I also take this opportunity to mention that the Alain Daniélou Foundation is opening an branch in Delhi next year in order to operate directly in India and link Italian, French, Swiss and German projects with similar initiatives and an expansion of horizons in southern Asia. The Ambassador of India in Italy, His Excellency Basant Gupta, has accepted to become President of the Alain Daniélou Foundation’s Administration Committee, taking over the task conscientiously fulfilled by Thierry de Boccard during many years (after which Mr. Boccard has certainly a right to delegate that responsibility and retire). Mr. Gupta’s decision honours the Alain Daniélou Foundation and brings new promises for the years to come, since he will be in charge of the Alain Daniélou Foundation’s activities in India and will work closely with Riccardo Biadene and Adrián Navigante with a view to setting in motion the best of projects on both continents.

It is with this spirit of creativity – budgetary difficulties notwithstanding, a situation our Foundation shares with many other cultural institutions – that I wish to extend to you my best wishes for the New Year. It is our hope that, focused on Alain Daniélou’s work fostering mutual respect between cultures and a way of living in a harmonious understanding of creation, the Alain Daniélou Foundation may provide an example of the type of responsibility human beings may assume in their adventure on this earth. This is especially important in these times of crisis and general disorientation.

Jacques Cloarec

Honorary President of the Alain Daniélou Foundation

Yoga and Religion: on Alain Daniélou’s “Method of Re-Integration”

Adrián Navigante – Alain Daniélou Foundation Intellectual Dialogue

Reading Daniélou’s book Yoga: The Method of Re-Integration today is quite a challenge. Not because the book was published in 1949 – since when Western perceptions of yoga have drastically changed from the first half of the XX century -, but rather because its contents and especially the framework of presentation notably differ from well-known treatises available to the ordinary Western reader today. As in other books dealing with the diversity and complexity of the Hindu tradition (such as his monumental Hindu Polytheism, published in 1964), Alain Daniélou does not endorse the scholarly point of view based on a scientific description of the sources, i.e. a strong desire for objectivity that usually forgets – or deliberately ignores – the complex question of what Hans-Georg Gadamer called the “history of effects” [Wirkungsgeschichte](1). He concentrates rather on the not-so-clearly-delimited line between primary written sources and oral transmission. This line depends on a fundamental orientation in thinking and experience; it is thin and diffuse, owing to the essential and paradoxical relation between the variety of historical transmission and the centrality of traditional authority: essential because transmission, being vertical, manifests and codifies itself in history, and paradoxical because the highest authority escapes legitimation. In this respect Daniélou clearly bases his interpretation of written sources on the authority of oral transmission, partly because he himself tackled the contents of Hindu tradition like any Shaivite acolyte (that is, receiving the “stream” of transmission: srota) through direct and permanent contact with paṇḍits and sannyāsins during his Benares period. But it was also because this was the key to proposing a new interpretation of archaic religious sources in Western culture, linking what he deemed a Dravidic substratum of Shaivism with such manifestations of Western religiosity as that of the Sumerian or Minoan heritage and later on with initiatic or mystery cults like the Dionysian in Greece or the Mithraic in Rome. Such topics are not at all alien to his yoga book. On the contrary, they define his understanding of the term “re-integration”, as we will see in the course of this essay and especially toward the end.

The introductory part of Yoga: The Method of Re-Integration consists of an exposition of the framework Daniélou deems necessary for a proper understanding of yoga itself. This framework also marks a particular approach that is initially difficult to grasp owing to the complex way in which it questions mainstream understanding of yoga related to the Vedāntic approach so widespread in Western culture. If we take classical definitions of yoga like that of the Katha Upaniṣad II.3.11: “yoga is the steady restraining of the senses” [yoga sthirā indriya dhāraṇā], the Yoga Yājnavalkya I.44: “Yoga is the union of the individual soul with the transcendental Self” [saṁyogo yoga jīvātma-paramātmanoḥ], or even Patañjali I.2: “Yoga is the coming to standstill of the whirls of consciousness” [yoga citta vṛtti nirodhaḥ], the difference between sense perception (and all modalities of individuated consciousness) and transcendent knowledge (or realization of the pure Self) appears to take the form of a judgement value, rejecting the former as a condition of achieving the latter. Vedāntic explanation of modes of non-knowledge [avidyā]can be easily joined to such yoga definitions just as they are applied to a central passage of one of the Mahāpurāṇas, the Śrīmadbhāgavata (III, 7.2.). In this mediaeval devotional text, the personified Self is said to be completely spiritual [cit-mātra], immutable [avikāra]and unadulterated by manifestation [nirguṇa](2). The whole aesthetic play of Krishna (including, of course, the erotic scenes with the gopīs) is thus justified by the word krīḍā and its opposition to kāma: Krishna – unlike human beings indulging in sensual pleasures – is detached and self-satisfied; he does not need that kind of pleasure because he lacks nothing. In the yoga practitioner the distillation process should therefore re-arrange the constitutive guṇas in order to purify his inner tendencies, his behaviour and lifestyle, since the practice of yoga is oriented toward the realization of the highest Self and not to mundane pleasures (3). Daniélou’s exposition of yoga challenges this assumption without wholly questioning the Yogic path of self-realization as a realization of Self. His exposition is threefold: 1. For him, the Yogic method does not reduce sense perception but amplifies it, leading to experiential knowledge of what is usually called “the supernatural”. 2. His transcendent aesthetics are linked to the type of knowledge identified in Hindu soteriology by the term avidyā. 3. With a Tantric turn based on his own interpretation of Shaivism, he detaches the path of self-realization from any moral imposition leading to drastic oppositions between “good” and “evil”, or between “pure” and “impure”. We will briefly take a look at each of these aspects.

From the very beginning, Daniélou relates the practical philosophy of yoga to an approach to the divine through the senses and not through the intellect. Apart from a critique of Platonic-Christian dualism, such a statement implies drastic modifications as to how classical yoga texts are to be interpreted, and Daniélou is fully aware of that. “The methods of yoga”, he writes, “may appear surprising and even offensive to the Westerner, imprisoned as he is in his conception of the superiority of the intellect, who finds some difficulty in understanding that any form of enjoyment, if not a realization of the Divine, is a first image of it, and that he only needs to go beyond this to find beatitude” (4). The kind of continuity between mundane enjoyment [bhoga]and spiritual union [yoga]may shock not only many a pious Christian but also more than a few orthodox Vedāntins, even when bhoga is assumed to be defined within the framework of viveka [discrimination, and therefore moderation]and is consequently preserved from utterly transgressive practices like those carried out by sects such as the Kapālikas and Aghoris. From Daniélou’s perspective, going beyond the pleasure of the senses does not involve rejecting such experience, but rather taking it to the point where it transcends itself. The main problem lies not in the limitations of the senses (to which one may counter the limitlessness of thought), but in finite modes of experience (that is, individuated perception and thought) with regard to a kind of knowledge free from all limitations yet still located within the realm of experience.

Daniélou retraces the transcendent modality of experience to animistic religion. While many theoreticians have characterized this archaic form of religious experience in a negative way (because the whole past century in the West can be seen as the offspring of Frazer’s The Golden Bough), Daniélou tends to retrieve its particular value, since animism “senses a conscious presence […]in all things” (5). To the secularized consciousness of the West, each thing has an objective status, involving an unbridgeable distance (an absence) between the subject perceiving it and the thing itself. Modern scientific thought proposes a transformation in absentia to compensate this loss by turning the thing into an object of analysis, but this is to the detriment of the natural order of things (the perception of which is, in a world dominated by the scientific attitude, embodied in the “merely subjective” realm of aesthetics). From Daniélou’s perspective, the perception of a conscious presence in each thing discloses a supernatural dimension within the immanence of nature – something that is invisible to the modern eye. Monotheistic religions are a dangerous simplification of the animistic attitude, because “they confined themselves more and more to the elaboration of a comforting fiction […]and to the pretence of issuing divine sanctions concerning man-made institutions” (6). From this passage it is clear that what Daniélou criticizes in monotheistic religions is the loss of any transcendent aesthetics leading to realization of the metaphysical level of existence through direct experience. It is precisely for this reason that he defines yoga as “the total religion” (7). The notion of totality is very important, since its main point is linking rather than severing: the metaphysical level is not separate from the physical; it is a continuation of it and can be achieved through an expansion of perception.

If we approach the problem of the opposition of metaphysical ignorance [avidyā or ajñāna]and transcendent knowledge [vidyā or jñāna], the fact of continuity in terms of degrees of perception does not imply that no specific technique is needed to achieve what Daniélou calls “perception of the divine” (8). Furthermore, the specific technique required to access the hitherto concealed dimension of experience can even be presented as a counter-movement to the perceptual habits of ordinary experience. This is the case of the fifth step in Patañjali’s yoga darśana, called pratyāhāra [withdrawal of the senses]. Daniélou’s explanation is quite clear: “The process of withdrawal consists in disentangling the senses, sight, hearing, etc. from the objects of their natural perception always linked with the opposing tendencies of attachment and aversion” (9). It is interesting to notice that he explicitly mentions two important forms of affliction [kleśa]from the five listed in the classical yoga doctrine: rāga and dveṣa (cf. Yogasūtra II, 3), but the others are implicitly present within the constellation of limited sense perception. If the senses are entangled (by permanent tension varying from attraction to rejection and vice versa) in the partial reality of the objects of their perception, limitation can be easily related to the individuated form of consciousness [āsmita = I-am-ness]that synthesizes experience and causes us to cling to life [abhiniveśa in the sense of mā na bhūvam bhūyāsam = let me not be non-existent]. The notion that explains this permanent limitation is avidyā, the sense of which is a privation of metaphysical knowledge (10), but this privation is for Daniélou a limitation in perception. That is why pratyāhāra is simultaneously the opposition to a habit and the extension of a faculty. What kind of perception can be achieved by disentangling the senses from objective reality? If cerebral activity is “the obstacle”, it is because the brain is the concrete instance of individuated consciousness, a “centripetal organ which makes each one of us the centre of the world” (11). This kind of centralization of experience occurring in each individual actually reveals itself as a fragmentation process in which each being loses its primordial contact with the rest. This primordial contact is the ontological identification that Daniélou aims at in describing the process of re-integration: the method of yoga “enables us to penetrate the most secret forms of matter and the universe, to perceive the nature of mental thought and consciousness” (12). With this last phrase he does justice to a fundamental idea of yoga philosophy: the progressive expansion of perception from limited sense awareness [indriya pratyakṣa]to mystic identification [yogi-pratyakṣa](13). The nature of mental thought and consciousness is certainly not to be found within the sphere of thought or individuated consciousness, but rather in the clear and direct intuition of “the indivisible complex consisting of thought, matter and life” (14). According to Daniélou, this direct intuition is mindful of that instinctive feeling of the supernatural that characterizes the earliest religions, in which “there is no dualism in the form of a distinction between God and the World” (15). In spite of the problematic homologation of the instinctive and the intuitive and the lack of nuanced consideration with regard to different forms of conscious activity and cognition throughout history, Daniélou’s rehabilitation of animism and the continuity line he traces with regard to yogic forms of perception remains a very interesting challenge in rethinking the crisis of modern man in the light of certain attitudes and methods deemed to be part of a distant past or structurally alien to Western development.

Perhaps the most difficult aspect of Daniélou’s book on yoga is the way he introduces fundamental Tantric variations to the classical conception of it, especially when determining the metaphysical value of yoga philosophy beyond all moral precepts. Many questions may arise at this point, some of which are impossible to answer within the frame of this essay: What does Daniélou understand by “morality” and to what extent is that judgement objective enough? Does he take into account – in his analysis of the classical yoga system – the abstinences [yama]and restrictions [niyama]that enable the sādhaka to follow the yogic path in a serious manner? Why does he isolate morality from other manifestations of cultural relativity preventing, in almost the same way, a radical metaphysical turn in the life of the practitioner? In what way can this turn be considered “Tantric” and what are its main features? Does Tantra, according to Daniélou, mean “utter transgression”? First and foremost, he declares quite clearly that since “the only aim of yoga is total re-integration, any other aim or tendency, be it worldly, religious, moral or intellectual, is […]an obstacle to yoga“ (16). In the practice of yoga ultimately leading to non-differentiation between absolute perception [yogi-pratyakṣa or nirvikalpa]and intuition of the absolute [pratibhā](17), all categories implying cultural distinction (even religion and thought) are to be overcome, and moral precepts fall within that category. Daniélou recognizes the main problem in attachment and the whole related spectrum of human bondage. On the level of human attachment, even pleasure (aesthetically celebrated by Daniélou himself) becomes a serious obstacle (18). However, the problem does not lie in pleasure itself, but rather in the modality of experiencing pleasure that depends on a reduced spectrum of conscious perception. In other words, there is for Daniélou a fundamental continuity in the three forms of life intensification: pleasure [sukha], happiness [prīti]and bliss [ānanda]. In this view, the state of dispassion [vairāgya]does not refer to any suppression of pleasure, but to non-identification with – and therefore non-dependence from – the finite object of perceptual stimulation. Daniélou does not forget that in Hindu mythology the intensity of pleasure acquires cosmogonic dimensions and the highest form of bliss has fundamentally erotic significance: “The state of repose or peace is […]represented by the union of opposites in a kind of continual coitus. Separation of the two poles creates instability, which gives rise to the creation of a universe of movement whose elements aspire toward union” (19). In reading this formulation and relating it to the uses of (detached) pleasure in Yogic practice, it is not difficult to see that we are confronted with some presuppositions of Tantric doctrines, especially the parallel between the microcosmic of the body and the macrocosmic forces of the universe and the tendency to harness desire [kāma]and all its related values to the service of deliverance (20).

Perhaps the clearest feature of Daniélou’s Tantric turn in his interpretation of classical philosophy and the practice of yoga resides in the role he ascribes to Shiva in the scheme of the three guṇas and its relationship with yogic soteriology. At the very beginning of his book, Daniélou paraphrases Patañjali’s well-known definition of yoga: “In order to understand yoga and its techniques it is essential to bear in mind that the incessant movement of cerebral thought forms a mist which conceals the Divine from our perception […]. To go beyond this all that is needed is to overpass the senses so as to perceive the inner harmony which underlies the harmony of the forms” (21). In Patañjali’s Yogasūtra I.2. yoga is associated with citta vṛtti nirodhaḥ, that is with a progressive purification of consciousness by means of which the confusion of identity between the fluctuation of mental processes [vṛtti]and the real state of pure and unlimited consciousness [puruṣa]is eliminated. In the most important exegetic treatise on the Yogasūtra, the reality of consciousness [citta]is characterized in terms of the three guṇas, in which sattva is associated with true knowledge [prakhyā]and has the nature of light [prakāśa](22), whereas tamas (as the opposite pole) is related to dispersion and therefore vice, false knowledge, attachment and a stupefied state of mind devoid of all supernatural insight [a-dharma-a-jñāna-a-vairāgya-an-aiśvarya](23). Thus the practical goal of yoga is seen (in spite of theoretical differences and rivalries) from the point of view both of Vedānta and the old school of Buddhism [theravāda]. Reintegration appears as a counterflow [pratiprasava]or an involution process of the guṇas, or in other words, movement away from the dispersion and numbness of consciousness represented by tamas. The main point is that, within this frame, the central goal can only be achieved by means of a “sattvification” of vṛttis leading to overcoming their effect as factors of affliction and suffering [kleśa, duḥkha]. With his emphasis on the aesthetic dimension of experience, Daniélou introduces another perspective that may very well be associated with vāmācāra, that is, the “contrary way” (or “left-hand practices”) of attaining self-realization, clear from his favourable treatment of desire and pleasure, which in his eyes do not lead to confusion, vice and perdition, but rather to religious voluptuousness as the ultimate expression of the divine (24). Daniélou relates the centrifugal force that disentangles individuals from their limited perception with Shiva, whose nature is not identified with sattva but with tamas. He explains this point very clearly in his book Hindu Polytheism: “Tamas, the centrifugal tendency, the tendency toward dispersion, dissolution, annihilation of all individual, cohesive existence, can be taken as the symbol of dissolution into non-Being, into the unmanifest causal Immensity. It thus represents liberation from all that binds, all that is individual and limited […].” “Tamas is associated with death, evil, inaction where action alone seems to bring results. Yet from the point of view of spiritual achievement, where action is the main obstacle, sattva is the lower state, that which binds with the bonds of merit and virtue, tamas is the higher state, that of liberation through non-action” (25). Such elaborations of Daniélou’s have a double basis: 1. The mode of classification of the genre “Purāṇas” as found, for example, in the Matsyapurāṇa (a work very often quoted by Daniélou), which states that the Purāṇas glorifying Shiva and Agni are those permeated by tamas (26). 2. A subversive line in the conception of self-realization, the sources of which can be found in a number of texts going from the Maitrāyaṇīya Upaniṣad (between III c. BCE and I c. CE) to the Mahānirvāṇa Tantra (XVIII c. CE), in which tamas appears as primordial Non-being (27) and Shiva – as Mahākāla (dissolver of the universe) – is associated with the highest liberation (28).

The Shaivite component in Daniélou’s book on yoga is not only functional in introducing the perspective of self-realization based on the left-hand path as a valid option to the more widely known classical line. The first part of Yoga: The Method of Re-Integration also presents very provocative elements going beyond any immanent treatment of Shaivism within the Indian subcontinent and dealing with a very strong thesis on matters of comparative religion. One clear example of such elements is the affirmation that “the teaching of yoga and the Shaivite conception of the world have survived barbarian invasions and dogmatic religions by resorting to a greater or lesser degree of dissimulation, only to re-emerge whenever mankind turned anew toward the cultivation of true spirituality” (29). The barbarian invasions Daniélou talks about are those of the Aryans (30) and among the dogmatic religions not only Christianity and Islam receive Daniélou’s attention but also Buddhism, Jainism and even Vedism (31). On the other side we are presented with a constellation of Indo-Mediterranean elements pointing to a religion of direct experience that Daniélou identifies (even with some Nietzschean undertones) as “Shaivite-Dionysiac” (32) and puts forward as a possible solution for the crisis of the modern Western world. From this point of view, the meaning of “re-integration” seems to change (or expand) from an individual axis of spiritual liberation to a collective one of cultural regeneration, and it revolves around those religious proto-forms that were never lost but remain at a seemingly unbridgeable distance from the immediate possibilities of our civilization (even within the framework of small communities). Faced with such enigmatic and daring intuitions, the reader desirous of doing justice to the tenor of the book is compelled to embark on a thorough consideration of the intricate link between Tradition, time and the modality of existence of what is called “the supernatural” but ultimately belongs to the unexplored spheres of the immanence of nature. Be that as it may, the amplification method of Daniélou’s yoga book remains a challenge on different levels, far beyond the book’s remarkable technicalities in both analysing and summarising the subject matter.

Notes:

(1) Cf. Hans-Georg Gadamer, Wahrheit und Methode: Grundzüge einer philosophischen Hermeneutik, in: Gesammelte Werke, Band 1, Tübingen, Mohr Siebeck, 1990, pp.305-312.

(2) Nirguṇa literally means “devoid of qualities”. The term guṇa is related to a triad of ontological qualities metaphorically depicted as three colours (white, red and black corresponding to sattva = clarity or light, rajas = agitation or excitement and tamas = darkness or lethargy). This idea can be traced back to the earliest Upaniṣads (for example Chāndogya Upaniṣad 6.4. or Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad 4.5.) and finds its full expression in the Sāṁkhya philosophy, according to which the guṇas are constituents of the single cause of creation [prakṛti]. It should be pointed out that according to the Bhāgavata Purāṇa “there is ultimately no ontological distinction between the Brahman of the Upaniṣads, the Paramātman of the yogins and the Bhāgawan of the Bhakti tradition” (D. P. Chattopadhyaya (ed.), History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization, Volume XVI, Part 4: Synthesis of Yoga, edited by Kireet Joshi, Delhi, Centre for Studies in Civilizations, 2011, p. lvvii).

(3) A clear example of this is given in the Bhagavad Gīta XVIII, 36-39, in which the division of the guṇas is recaptured on the level of “types of pleasure” [sukha]. Tamasic pleasures like sleep, sloth and distraction, and rajasic enjoyment (related to the senses) have a clearly negative connotation, whereas sattvic enjoyment is the only real elixir – precisely because of its spiritual nature.

(4) Alain Daniélou, Yoga: The Method of Re-Integration, London, Johnson, 1973 (fourth printing), p. 3.

(5) Alain Daniélou, Ibidem., p. 5.

(6) Alain Daniélou, Ibidem., p. 6.

(7) “Yoga is the total religion because it does not separate the metaphysical level from the physical and mental levels“ (Alain Daniélou, Ibidem., p. 9).

(8) Alain Daniélou, Ibidem., p. 3.

(9) Alain Daniélou, Ibidem., p. 82.

(10) This completes the scheme of Patañjali’s verse on the kleśas: avidyā-asmitā-rāga-dveṣa-abhiniveśaḥ kleśāḥ (II, 3).

(11) Alain Daniélou, Yoga: The Method of Re-Integration, p. 3.

(12) Alain Daniélou, Ibidem., p. 10.

(13) The term pratyakṣa is very important because it points to the immediate evidence of perception. Buddhist thinkers of the Vijñānavāda tradition (notably Diṅnāga and Dharmakīrti in the VI and VII centuries CE) developed a useful classification of the types of pratyakṣa covering the different spheres of perceptual cognition, most surely with the aim of giving a more precise definition of the term itself.

(14) Alain Daniélou, Yoga: The Method of Re-Integration, p. 7.

(15) Alain Daniélou, Ibidem., p. 6.

(16) Alain Daniélou, Ibidem., p. 130.

(17) “The Self-consciousness, which is All-consciousness, is Pratibhā in the light of which all things are simultaneously (akramam) and in all their aspects [sarvathāviṣayam]revealed. It constitutes the highest mystic acquisition of the yogin” (M. M. Gopniath Kaviraj, Selected Writings, Delhi, Indica, 2006, p. 18).

(18) As Daniélou himself openly recognizes in his analysis of Yoga Darśana, cf. Yoga: The Method of Re-Integration, pp. 130-131.

(19) Alain Daniélou, The Hindu Temple. Deification of Eroticism, Rochester: Vermont, Inner Traditions, 2001, p. 8. Cf. also Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad I, 4.3., also quoted by Daniélou.

(20) Cf. Madeleine Biardeau, Hindouisme : anthropologie d’une civilisation, Paris, Flammarion, 1981, pp. 149-150, cf. Hugh Urban, The Power of Tantra: Religion, Sexuality and the Politics of South Asian Studies, London: New York, I.B. Tauris, 2010, p. 19.

(21) Alain Daniélou, Yoga: The Method of Re-Integration, p. 3.

(22) Cf. Yogasūtra II.18. and its direct association of sattva with light.

(23) Yogabhāṣya I.2.

(24) “The divine state is a state of joy, of immense happiness and well-being, and it is in sex that our power of enjoyment is concentrated, a power which, for an instant, enables us to partake of the beatitude of the divine state” (Alain Daniélou, Yoga: The Method of Re-Integration, p. 14).

(25) Alain Daniélou, The Myths and Gods of India. The Classical Work on Hindu Polytheism, Rochester: Vermont, Inner Traditions, 1991, pp. 22-23 and p. 26.

(26) Matsyapurāṇa, 53. 68-69. This passage is commented by Greg Bailey in his essay on the Purāṇas written for Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism, see: Knut Jacobsen (ed.), Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Volume II: Sacred Texts, Ritual Traditions, Arts, Concepts, Leiden: Boston, Brill, 2010, 134.

(27) “Verily this was first only tamas” [tamo vā idaṁ agra āsīt], Maitrāyaṇīya Upaniṣad, 52. Cf. Mahānirvāṇa Tantra 4.9.

(28) Mahānirvāṇa Tantra 4.30. In a footnote to his translation, John Woodroffe adds, “A Tāmasic form of Śiva as He who dissolves all, under which he is represented as of a black colour of terrific aspect” (cf. John Woodroffe, The Great Liberation (Mahānirvāna Tantra), Madras, Ganesh and Company, 2006, p. 69.

(29) Alain Daniélou. Yoga: The Method of Re-Integration, p. 7.

(30) The Aryan invasion thesis is nowadays not only contested by some historians but also virulently rejected by Indian authors attempting a strongly homogenous reconstruction of their own tradition. In the case of Daniélou it has to be borne in mind that his arguments are (like those of the supporters of the migration theory) linguistic in nature and focus on a rehabilitation of a native substratum of Indian culture alien to (and logically older than) Vedic civilization. Klaus Klostermaier is right in saying that “the scholarly debate has largely degenerated into an ideological battle” (A Survey of Hinduism, Albany, State University of New York Press, 2007, p. 20), so the question (for which there is no substantiating evidence on either side) does not deserve further treatment, at least within the frame of this essay.

(31) There is of course a nuanced consideration of some of them, something that may escape the attention of a reader who remains on the surface of Daniélou’s provocative style. He recognizes the value of Suffism, Vajrayāna or Tantric Buddhism, the teachings of Jesus in the canonical and apocryphal Gospels (on condition of their being detached from the message of St. Paul), and the social stability and coherence of Indian society based on Brahmanic principles.

(32) “The interest, although ill-informed, aroused today by yoga and Indian thought is perhaps an indication of a return to Shaivite-Dionysiac concepts in the disturbed world of our time“ (Alain Daniélou, Yoga: The Method of Re-Integration, p. 7).

Around Our Corner

Samuel Buchoul: researcher and writer in India and Europe

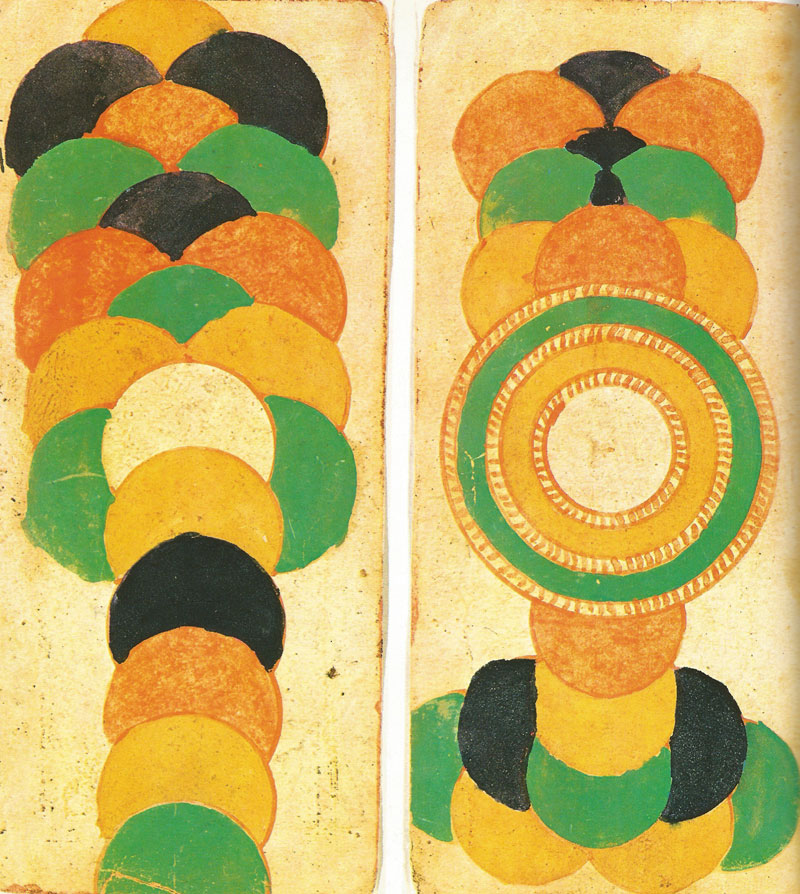

Two from a set of thirteen leaves from a manuscript illustrating

Two from a set of thirteen leaves from a manuscript illustratingthe processes of projective evolution of the universe. Western India, c. 1700.

Source: Philip Rawson, The Art of Tantra, London, 1973

The rhythm of the seasons — winter has opened up again, it feels cold outside. Last time too, winter hit, marked like burning iron, right at its heart, in early January. Seasons, months have their cycles, their repetitions always a bit different, cumulative, but this year seems marked irrevocably, we call it “2015”, a temporal scene for what many have seen as the entry of France, of Europe, into a new phase of “world history”. Yes, the cycle regularly breaks — somewhere between months, seasons and years, each time, Nature stops and enters History. From the cycle to the linear. The Past is behind us, only the Future is ahead: we must respond. Happy New Year!

419 964 B.C.E From India to Europe, Daniélou brings spaces across times. “The Theory of Cycles”, a section from his While the Gods Play (La Fantaisie des Dieux et l’Aventure Humaine) proposes colouring, not unpleasantly, an ancestral doctrine in the shades of our language of today. Myths find their translation in “our world”:

Tasteless mix des genres or long-awaited bridge between cultures? Daniélou’s text is passionate, confident, deaf to the dictates of “academic norms” and their partiality, certainly as powerful thirty years back as they are today. Daniélou writes differently, he writes as he felt, as he experienced, as he lived and learnt, humble and receptive to another story, different in its content but also in its methods. There seems to be an echo of the introspective, traditional teacher, when Daniélou decides to quote at length the Linga Purana or Vishnu Purana, knowing that his touch is not missing, even if his commentary only adds a few more lines to the long quotation. Daniélou lived another experience of knowledge, and yet he also brought it back to a Western audience. Not only through publication, when many translations already abound, but by mixing languages, by attempting to bring translation to another depth. By playing with “science” and its idiom, perhaps, with the myths of linear time, for instance, for provocation’s sake if nothing else. He suggests the following: we are part of the 7th human cycle, forcibly yet unconsciously modest before what is already a story half-a-million-years old: humans and humanities. 419 964 B.C.E: all of a sudden, the time frame pops, the scale widens, up to our own horizon… and far beyond.

As Christmas is nearing, we may remember, this time, the gift of Daniélou: he reminds us of the possibility of thinking and living on the long scale. Winter time, not too far from the cold showers and the wake-up call out of our cosy blankets: when our horizon of past human culture jumps from the 3,000 years of the Greek-Semitic-Roman-European-Global narrative, to 60,000 years — the beginning of the present cycle — and finally to 420,000 years. As the past moves back, each bit of the present changes form and colour. Migrations cramping lands, terrors throwing us towards “the last destruction”: as time and space seem to shrink, there is perhaps always Daniélou’s aplomb to remind us that our world has been much different, and much more than what our diminishing sight considers its limit: the supposed “foundations” of our world through the development and encounters of Greek and Semitic cultures in the course of the last three millennia. There was “something” before that, elsewhere, “faraway”, over there, in the comfortably distant lands of the exotic… but there was also “something” else here, right here — in the Athens of the philosophers, in the Jerusalem of the Christ, in the Syria of the Islamic State and in the Paris of the “2015 attacks”.

There was, and there still is. 13 November 2015, a weekend in France, young and old generations push away routine and jobs to where they belong, and go for a drink at a café. Day and night, evening, Friday, week, weekend, months, seasons: another time is there, and it is there not at the margins but right at the centre of our lives. Living through cycles, repetitions, rites and habits. But these attacks will be the “attacks of 2015” — enter “2015”, already taking over the memories of the attacks “of a winter Friday night in Paris”, the tyranny of numeration, system, measure, and thus reference, the unsurpassable reference. 2015 years after this reference, this point assumed as the neutral zero, as the beginning, but in fact culturally partial, intensely particular. As long as these are the “attacks of 2015”, resources and inspirations to respond correctly, or just to continue living faithfully, will be constrained by this frame — 2015, it was 2015, and even after the 31st December, it will remain 2015, forever. Fantasising that we are at our “beginnings” of culture, we will not be able to think and live those moments beyond Greek thought and Semitic religiosity.

Mentalities have evolved since the Charlie Hebdo attacks. While in the countryside, the old France of all ages confuses past and future by going for the blind pragmatism of the Front National, the younger generation, target of the 13th of November, is no longer proclaiming the slogans of “the Republic” and of the amalgamation of identities (“I am Charlie”). No, indeed — effective performance of democracy, the peuple questions the immediate reaction of the belligerent state, realising that its effects will be counter-productive, and the invoked roots of the situation erroneous. Away from our sight, the manicheaism of “the isolated criminals”, or even of “the barbarous organisation, arch-enemy of civilisation”. “It is the reactive psychology of a destroyed generation in the Middle-East”, we hear somewhere; “It is the oil economy”, others respond. Going further back in time, connections with colonial heritages are also mentioned. But always, the matrix of Greek-Christian values is the ceiling — history, science, objectivity, democracy, equality, representation, compassion are the silent assumptions. Digging the deeper roots of our inter-connected reality is always a welcome effort, but the question to ask thus becomes: When should we stop? Why should we take the so-called first millennium before the common era as the unquestionable bedrock for our chronology and our values? To this very thread of cultures, Daniélou submits: It is just the tip of the iceberg. Only the middle phase of the fourth and last age of present humanity: Kali Yuga, time of confrontations of differences, the age of destruction.

The intuition of the Yuga, putting on various cultural dresses across societies, would be thus a universal conception, beyond its Indian accent. There would be, besides and above the evident cycles of our everyday life, a stronger, long-scale conception of time that would transcend, and precede the positivistic, linear doctrine that took prominence in the development of our European civilisations. Returning to a cyclical understanding of time, and not just for the daily routine of our farmers and city-dwellers alike, is perhaps the actual challenge of this event, the opportunity of the moment of crisis (krinein): perhaps a real, profound decision that could finally extricate us from the entanglement of our questions and their solutions.

The specific details of this narration of time, proper to a certain lineage of Shaiva doctrine, further reinterpreted by Daniélou, is not decisive. In fact, a more classical “social scientist” approach would generally differ largely from Daniélou’s calculation, when it translates the various frames of the Yuga doctrine into the linear frame of Greek and Semitic time references. But Daniélou helps us make the jump — further underlining the deconstruction of the deepest assumptions of “the West”, he succeeded in demonstrating an alternative narrative that would be equally rigorous, potentially more powerful hermeneutically, and ultimately more empowering for each individual.

And this shift is effective beyond contemplative enquiries. “Returning to a cyclical understanding of time” — what would that imply? It may well point towards very concrete alternatives, far more practical than even global strategies and realpolitik. When our understanding of time moves from the line to the cycle, each temporal instance changes in nature. No more “events” in a cyclical time, no more politics with an ideological horizon and dream, but recurring patterns, playing roles and performing functions in the macro-cycles of the planet just as in the micro-cycles of each nation, each community, each relationship and each individual. “One of the fundamental conceptions of Shaiva philosophy is that each form of existence, animated or inert, each living species, has a role to fulfil in the play of creation…” (4) No more terrorists, no more democracy, no more before or after: references crumble and fall, and all pieces move on a much wider grid. In discovering cyclical time, the constructivism of a positivistic mindset is replaced by the internal connection of past and future in the present. When the line of time bends towards itself, the appearance of events shades off and something else emerges. But what?

As we round our corner, this occasion may present us with a long awaited re-discovery. Starting again to read our present through our deep past, the dimensions of time and space condense. Our landmarks have disappeared: a “disruption” separating a phase of time from its past, along a linear scale, becomes a reiterated scenario; while our political cognitivity, this fundamental undertone of our metaphysics of space, always gazing outside for fear of losing what is inside, gets reinterpreted as an introspective call, deconstructing and creatively arranging the universal categories of in/out and self/other. Condensation of time and space towards the inside — the echoes of a universal practice resurface: the ritual. If the attacks of 13 November were interpreted in a cyclical framework of time, then it may be our chance to call for the return of our rituals, so they may find their place more regularly, and integrate such apparent turmoil. In his Hinduism, Past and Present, Axel Michaels too considers moments of disturbance as renewed occasions for rituals:

“Yet human time is the only unit of measure that we can understand…” What could this “human time” become, once the lesson of Daniélou is heard and brought to fruition? As the scale of our past grows a hundredfold, each human life becomes unbearably smaller, seemingly insignificant before the dynamics of human cultures spread like tentacles over hundreds of thousands of years. But meaning survives and shines, for we are to find new modes of understanding. If the 3000-year-old narrative of European civilisation thus appears as a grave reduction, it is not for us to give up all hopes of cultural construction and collective values. Rather, we must open the scales, outwards and inwards. Digging thousands of years back for what the ancients of ancients had found as the bases of humanity’s balance, through the preservation of ancestral knowledge by marginal lineages, as in Daniélou’s understanding of Shaivism in India. But digging also inwards, intensifying the exercise of attentive presence, shunning all sounds to hear the heartbeat of silence, rhythm of the divine, ripples of the music of life: the internal manifestation of the cycle.

The cycle is not a denial of progression and change. Daniélou does not miss the important nuance: “The circle is an illusion, for the cosmic mechanism is in reality always formed of spirals. Nothing ever turns to its point of departure.” (6) Thus the cycle subsumes the line, but it can just as well take a linear avatar, if needed for understanding, for the creation of meaning and thus for the empowerment of action. The programme of the short-sighted “European line” of democracy’s time, for instance, with its naive end point, is behind us already, but the larger scale of the future draws itself still, through and beyond the predictability of the upcoming cycles.

Daniélou calculates the end of the present Kali Yuga for 2442 C.E. For provocation’s sake if nothing else, once again, it may be worth considering this prediction, and what that may imply for the ethico-political challenges of our times. When we expect the escalation to extremes to go on for four more centuries, it is not the umpteenth “alliance against terror” that should preoccupy our thought and imagination, but rather all the episodes of creativity and destruction that will undeniably mark our world in the span of time that may separate us from our actual end. And, what role we may play in this large, cosmic drama, even if partially rigged. This was probably the scope Daniélou had in mind, thirty years ago, as he wrote another appeal… concluded with a surprising request, final cerise sur le gateau after a copious meal of surprises:

From rites to Yoga: what stories connect the two? Tasteful meditation on the channels of the rasa? Circumvolution of thought like a cycle around the curves of an ॐ-like chakrasana? Daniélou leaves us once again in suspense, guessing, comfortable in the ellipsis: …

Notes:

(1) Daniélou, Alain. While the Gods Play (Inner Traditions International, 1987): 191-192.

(2) While the Gods Play, 197.

(3) While the Gods Play, 16.

(4) While the Gods Play, 225.

(5) Michaels, Axel. Hinduism, Past and Present (Orient Longman, 2005): 311

(6) While the Gods Play, 196.

(7) While the Gods Play, 208.

Shiva in the Work of Alain Daniélou: Archetype and Reference Figure

Anne Prunet: Alain Daniélou Foundation Advisory Committee

(translated from the French by Kenneth Hurry)

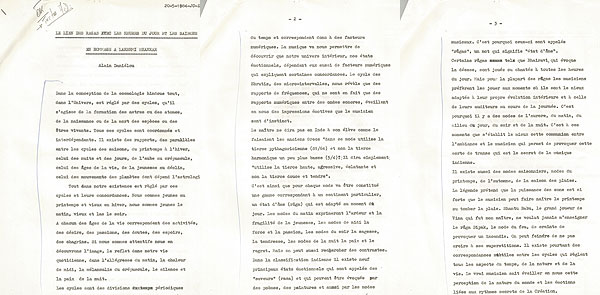

« Lingodbhavamurti, Shiva emerges out of the linga ». Tamil Nadu, 12th Century.

Source: Johannes Beltz (ed.), Shiva Nataraja. Der kosmische Tänzer, Zurich, 2008

The figure of Shiva, as it appears in the work of Alain Daniélou, is worth studying with regard to this author’s position in society in his chosen country: India. Not being born in India, Daniélou’s status was that of a mleccha (1), that is, a foreigner. As such, he was classed as one of the shudras, whose rules he had to follow (2), but he performed the rites and purifications required for him to study with Brahmins and was thus designed as “a shudra who practices the customs of Brahmins” (3).

The Changeling: a status apart

Alain Daniélou felt he was driven to quit his native land, where he could not find his place. This feeling of being apart is expressed in a text published in Le Figaro under the heading: “Les écrivains et leur pays d’élection” [Writers and their Chosen Lands](4). In it, Daniélou does not merely express his attraction for India, but first and foremost a feeling of not fitting in the world in which he grew up: “The old Breton woman who looked after me during my childhood told me that the fairies, who have no milk, are forced to abduct a human baby, replacing it with their own child in the cradle. The changeling grows like other children, but feels a stranger in the world that surrounds him. One day, through odd words, he betrays his real nature and must then depart in search of his true land. The old woman pointed out to me that I had two toes growing together forming a slightly cloven foot. What she concluded thereby was a secret not to be revealed to anyone. Poets, musicians are often fairy changelings, whom chance has caused to be born in an environment that is not their own, and which they must leave to realise their destiny.” (5)

This text emphasises firstly a feeling of being apart, but at the same time that of belonging to a group, that of artists and musicians. Daniélou also insists on the difficulty of not belonging to a set social group, since marginality is not a supplementary attraction created by the artist, but a difficult, albeit ineluctable, situation through which he realises his life, together with his work.

It is thus the stranger to his own family who decides to live in a culture in which the foreigner is not absorbed by the social structure, but occupies a very specific position. Now this overwhelming importance is attributed to a specific aspect of Shiva: the destroyer – the non-unifying pole, not integrated by cohesion, the necessary counter-balance for the very existence of every cohesive social structure. That is the way Shiva is presented by Daniélou in his work The Myths and Gods of India – Hindu Polytheism, within the context of the major deities and figures of Hinduism: “In the trinity, Vishnu the Immanent is the name given to the cohesive or centripetal tendency, which is called sattva. Everything in the Universe tends towards the centre, toward a greater degree of concentration, of cohesion, of existence, of reality: Whatever tends to create light, truth, is represented by Vishnu. Shiva, the centrifugal principle, on the contrary, represents dispersion, annihilation, tending to darkness, to non-existence” (6). We should note that this figure of Shiva is linked to non-being: as in the anecdote of the fairies, the exceptional child is non-human. The second common point is the movement away from the centre, just as the figure of the artist is on the margin of the society in which he grew up, just so Shiva represents the force that his power of attraction exercises toward the exterior, effectively toward the margin. Lastly, we should note that Shiva only exists because Vishnu creates that cohesion from which he stands apart, but also that Vishnu only exists because Shiva creates the borders of his cohesive system.

The Figure of Shiva in the Work of Alain Daniélou

Shiva is consequently associated with a multitude of symbols that put him on the side of nomads, strangers, travellers, thieves, and Vishnu of the side of the settled, the city-dwellers, the materialists. It is not surprising therefore that Daniélou took an interest in this figure that simultaneously represents the artist, the traveller and the stranger. Many of his works include a greater or lesser examination of the god Shiva. Shiva and Dionysos compares the Hindu and Greek gods; in While the Gods Play, man’s role in the world is examined according to Daniélou’s view of the Shaivite tradition.

Thus, Shiva is omnipresent in the author’s work, although Shaivite Hinduism represents a minority view in the India in which he lived. His is therefore a real desire to highlight a figure who reveals – even in his own eyes– his path. This figure represents what Western society deems negative values. The first quality to be noted is that of the nomad and heretic: “Shiva is the god of the Shudras. He does not enjoy good press amongst the sedentary holders of knowledge of the city: he wanders about cemeteries, smears himself with ash from funeral pyres, he laughs, weeps, walks about naked. He is mad, adored by the mad (…). They are merely heretics who oppose the true faith” (7). Just like Dionysos, Shiva is the god who is banned from society: he is the god of nature and of the people. While Dionysos is insulted and expelled by Lycurgus, King of the Edonians, Shiva is not invited by Daksha to the banquet of all the gods (8). In both cases, Shiva and Dionysos sate their vengeance in blood. Daniélou explains why the god and his followers are deemed heretics in modern Hinduism: “the Shaivites, because they abandon the Vedic rites, are considered vrātyas (heretics)” (9).

Another of Shiva’s qualities is that of being from nowhere: for this reason, he wanders about the world, without ties, without material goods or clothes: “The true man is naked. It is the hypocritical and Pharisaic religion of the city that imposes clothes. Shiva is naked. Shaivite sages and monks wander naked through the world, with no ties” (10). This wandering is emphasised by the author, when he states that numerous texts of the Graeco-Roman tradition “mention the wandering of Dionysos over hills and vales” (11). Furthermore, a sadhu is an outcaste in Hindu society, which means that a sadhu’s origin is no longer of any importance from the moment in which he embraces the life of a sadhu. Becoming an outcaste in such a codified society may appear to be a paradox, but it both underlines the need for a cohesive society and allows the exceptional individual to become an outcaste. Daniélou found his place in Hindu society with the pandits when they saw that he was entitled to receive their teachings, which gave him a special position described in Approche de l’hindouisme [Approaching Hinduism]: that of a shudra – one might add ‘Breton’ – practising the rules of Brahmins. Consideration of the Shaivite movement leads Daniélou to mention their followers, the sadhus, and in this connexion he quotes a passage of the Rig Veda describing them as the companions of Shiva-Rudra ‘with long hair, clothed with the wind’ (i.e. naked) (12). How can one not think of the archetypal description of Rimbaud, ‘the man with soles of wind’? Thus, the figure of Shiva echoes Daniélou’s status, raised to the level of a role model in Hindu society: stranger, traveller, artist. He does not even belong to the society in which he occupies a special place, the place of the exceptional man to whom the laws of the city do not apply as they do to others.

A mise en abyme of Otherness as necessary counterpoint to any outlook

Furthermore, the question of double nature is also connected to the god Shiva who can, depending on the circumstances, change into a woman. Here, the question of double nature involves two levels: the author’s relationship to this figure, simultaneously model and counter-model, and its inherent aspect of duality. This figure is not the author’s double, as it would be in an autobiographical novel, a process used by Daniélou particularly in the short story “Tages” in his Contes du labyrinthe [Tales of the Labyrinth](13). The connexion between the author and this figure is no less effective, however, and reveals his quest to give meaning to his chosen path by making reference to archetypal models. Shiva is a Hindu god of many faces and functions. Daniélou chose to highlight certain exemplary traits, bearing witness to a subjective choice, and the similitude to his own life reveals a need to pass through the prism of projection, despite the collective personalities revealed in his autobiographical data. Let us take the example of the short story “Tages” from his collection of Contes du labyrinthe. The two main characters, Gwen and Arno, are clearly similar to Alain Daniélou and Raymond Burnier. At the same time, the tale is not told by Gwen, but by an extra-diegetic narrator. It is consequently tempting to believe that Gwen is Daniélou’s double, especially with reference to Daniélou’s memoires, The Way to the Labyrinth. Many factors encourage such identification: the similarity of the tale and the passages of The Way to the Labyrinth under the heading “Zagarolo” (14) and “Raymond’s Death” (15). Gwen Arvis is presented as “a young Irish designer” and what he has in common with Daniélou is his Celtic origin. Relations between him and Arno reflect those between Daniélou and Burnier: they are friends and lovers. Arno has the same material and financial resources as Burnier, which successfully allow him to carry out artistic research. However, from this point of view, Arno’s situation is closer to that of Burnier at Benares. The Way to the Labyrinth tells us that Burnier rented Rewa Koti for a risible yearly amount, just as Arno buys the house in the hills for a very modest sum. Raymond specialises in photographing Hindu temples of the mediaeval period, in the same way that Arno draws the plans of the Etruscan towns of Latium, both involved in field work and artistic work. By means of these doubles, the story of Burnier and Daniélou is not only duplicated, but reconfigured, since certain episodes of their years in India are moved into an episode of their life in Italy. The search for a house and moving in have the same dynamics in both accounts. Furthermore, the locations are very similar: one of the small towns known as the Castelli Romani, nestling in the hills a few kilometres from Rome. In The Way to the Labyrinth it is Zagarolo, in the Contes Zagardo. The history and rich ancient past of the place are described in both texts. The two friends immediately feel at home in a location so charged with history. Raymond or Arno, however, is enthusiastic about the house, whereas Gwen or Alain is wary of it. In The Way to the Labyrinth, Alain says, “However, I didn’t like the beautiful house Raymond moved into. I felt uneasy there. It gave me an impression of evil” (16). In Les Contes du labyrinthe, the narrator lays bare the contrasting opinion of the two friends: “Arno was visibly attracted by it, but Gwen remained uncertain” (17). A few lines further on, we learn that Arno adjusts to the house, whereas Gwen “always feels ill at ease”. In both cases, Gwen or Alain escapes from the house and goes to live a few hundred yards away in a ruin, an old vine-dresser’s cottage. What follows is also parallel: Arno, like Raymond, falls a victim to malevolence and dies poisoned in his beautiful home, to the great despair of Gwen or Alain, powerless to do anything, but unsurprised at this fateful outcome. The malevolent and unscrupulous character, Franco, who leads Raymond to his doom in The Way to the Labyrinth, is incarnate as Callisto who, like Franco, helps himself to the assets of the deceased and manages the inheritance, without Alain or Gwen being able to do anything about it.

We are therefore faced with the same story, recounted in a book (The Way to the Labyrinth) presenting a very clear referential allusion which is undermined from within, since the author vows that he has said nothing essential. In Les Contes du labyrinthe, the terms are fictional, but the author affirms in a foreword that the characters are real and the situations described more real than they appear to be. This double paradox explains the legitimacy of this double account of the same event and challenges the traditional generic categories giving rise to the self-fictional dimension in Daniélou’s work. Furthermore, behind this double paradox of an autobiographical account in which the essential is not said, and a fiction which is truer that seeming reality, one glimpses the filigree design of features or qualities attributed to Shiva. In the short story “Tages”, Gwen discovers his true origin and his identity thanks to ancient deities: “Vegoia told me you were coming (…) You are to some extent my brother, at least my half-brother! But half of you is stupid and doesn’t know who you are”. At this statement, the narrator protests, “I know very well who I am. How could I be your brother? I was born on an island in the north.” But Tages insists, “I know, I know. He whom you call your brother is not your brother, neither is your mother your real mother. You were with them for nursing” (18). Faced with Gwen’s incredulity, Tages invites him on a journey through time, which will reveal his true identity to him. So it is through deities who, in common with Shiva, are characterised as not belonging to the narrator’s universe, as representing a bygone world, lost in the mists of time (Shaivism represented for Daniélou the most ancient form of Hindu religion), as being worshipped by nomads, strangers, as well as artists, that the character (Daniélou-Gwen) discovers not only his true origin, but more particularly the path that makes him happy (19).

Poetics of the Margins

Daniélou’s writings, borrowing features from figures other than the author’s own (real or fictional figures, human or divine), have a dimension that could be described as exo-biographical (20). Such forms of writing are not really categorised as a genre and thus appear to chime with writing about alterity, otherness, expressed outside any categorised genre. Concern for exhaustiveness and absolute veracity is of little importance, since the models are actually archetypal references. If one believes the critics, the autobiographical novel, qualified as “a hybrid monster that evades the poetry critic’s test-tube” (21), must be interpreted as an element of post-modern culture: “The decline of historicist dogma and mechanistic explanation opens the door to thinking on self-regulation, unpredictability and polymorphism” (22).

One of the features of post-modern literature is its shifting of borders and boundaries, even challenging the very notion of genre, as demonstrated by Jacques Derrida (23) who shows that studying a text in relation to its genre often leads to classification problems. Indeed, we should go back to what Todorov (24) qualifies as intermediate categories, which not only represent a minor part of the corpus, but also most of the works that follow a counter-pointing path, the borderline, both antagonistic and complementary to doxa. The figure of Shiva in Daniélou’s work is consequently emblematic of the author’s own non-dualist path, both in his thought and in his manner of expressing it, both content and form being closely linked in the woven words of the art of counter-pointing.

Notes:

(1) The term mleccha in India today carries even more pejorative overtones than in the nineteenth-fifties.

(2) Alain Daniélou, Le chemin du labyrinthe, Paris, Laffont, 1981, p. 149

(3) Alain Daniélou, Approche de l’hindouisme, Paris, Kailash, 2007, p. 160.

(4) Alain Daniélou, « Bénarès: cité des sages nus », « Les écrivains et leurs pays d’élection », Le Figaro, 10 juillet 1982.

(5) The version quoted is not the published one, but the more exhaustive draft of the text: Alain Daniélou archives, The Labyrinth, Zagarolo.

(6) Alain Daniélou, Mythes et dieux de l’Inde, Paris, Rocher, 1992, p. 229.

(7) Alain Daniélou, Ibidem., p. 135.

(8) Cf. Alain Daniélou, Shiva et Dionysos, Paris, Fayard, 1979.

(9) Alain Daniélou, Ibidem., p. 130.

(10) Alain Daniélou, Shiva et Dionysos, p. 69.

(11) Alain Daniélou, Ibidem., p. 66.

(12) Alain Daniélou, Mythes et dieux de l’Inde, p. 129.

(13) Alain Daniélou, Les contes du labyrinthe, Paris, Rocher, 1990.

(14) Alain Daniélou, Les contes du labyrinthe, pp. 240-243.

(15) Alain Daniélou, Ibidem., pp. 281-283.

(16) Alain Daniélou, Ibidem., p. 241.

(17) Alain Daniélou, Ibidem., p. 16.

(18) Alain Daniélou, Ibidem., pp. 22-23.

(19) Cf. The quotation from Aristotle that Alain Daniélou uses as an epigraph in his book Le Chemin du Labyrinthe: “the rightness of the path you have chosen will be measured by your happiness”.

(20) This term is borrowed from E. Germes and refers to the process of projecting biographical features on persons other than oneself. Cf. Etienne Germes, Segalen : l’écriture, le nom : architecture d’un secret, Paris, Presses Universitaires de Vincennes, 2001.

(21) Mounir Laouyen, « L’autofiction, une réception problématique », p. 8. http://www.fabula.org/colloques/frontieres/PDF/Laouyen.pdf, 2001.

(22) Mounir Laouyen, Ibidem., p. 8.

(23) Cf. Jacques Derrida, L’écriture et la différence, Paris, Le Seuil, 1976.

(24) Cf. Tzvetan Todorov, Les genres du discours, Paris, Seuil, 1996.

Alain Daniélou: The Connection of Ragas with the Hours of the Day and the Seasons

Translated by Adrián Navigante (Alain Daniélou Foundation Intellectual Dialogue)

This text was written in French by Alain Daniélou in May 1984 as a tribute to Hindustani classical vocalist

Lakshmi Shankar.

A facsimile of the original French text is annexed to the English translation.

In the conception of Hindu cosmology, everything in the universe is determined by cycles, from the constitution of the stars or the atoms to the birth and death of species or living beings. Each cycle is coordinated in a relationship of interdependence with all the others. There are connections, parallels between the cycles of the seasons from spring to winter, the cycles of night and day, of dawn and dusk, those of the ages of life from youth to decline, and those of the movement of the planets from which astrology depends.

Everything in our existence is governed by these cycles and their concordances. We are young in spring and old in winter, we are young in the morning and old in the evening.

Each of the ages of life is distinguished by certain activities, desires, passions, doubts, hopes and sorrows. If we pay attention, we can discover the image of these emotions, their impact on our everyday life: in the joy of the morning, the warmth of midday, the melancholy of dusk, the silence and peace of the night.

Cycles are periodic divisions of time, and are therefore related to numeric factors. Music makes us aware that our inner universe – our emotional states – is also dependent on numeric factors that explain certain concordances. The cycle of śrutis, or micro-intervals, reveals to us the fact that relations of frequency, which are nothing more than the numerical relationships of sound waves, awaken emotive impressions instinctively perceived by the musician.

An Indian master will never tell his pupil what the ancient Greeks used to say, “In this mode use the Pythagorean major third (81/64) and not the little bit lower natural third (5/4)”. He will simply say, “Use the high, aggressive and explosive third, not the sweet and tender one”.

In this way, a scale is created, belonging to a particular feeling, a state of the soul [rāga]. This spectrum is related to each mode and suited to the time of day. The modes of the morning express the ardour and fragility of youth, the modes of midday force and passion; the modes of the evening wisdom and tenderness, and the modes of the night peace and regret. But we can also observe contrasts. The Indian classification numbers nine principal emotional states, which are called “tastes” [rasa]and can be evoked by poems, paintings, as well as musical modes. It is for this very reason that they are called rāgas, a word meaning “state of the soul”.

Certain rāgas such as the bhairavī, which evokes the Goddess, are played and chanted at any time of day. For most rāgas however, musicians prefer playing them at the specific moments of the day to which they are best suited according to their inner evolution and that of the listeners during the course of the day. This is why there are modes of dawn, morning, midday, evening and night. At those moments there is a communion between the atmosphere and the musician, whose performance leads to a sort of trance revealing the secret of Indian music.

There are also seasonal modes, modes of spring, autumn, and those corresponding to the rainy season. Legend has it that the power of sound is so strong that the musician can even give birth to spring or induce rain to fall from the sky. Shantu Babu, the great vīṇā player who was also my master, never wanted to teach me the dīpak rāga, the mode of fire, because he was afraid that it would cause flames to break out. We may feign not to believe in such superstitions, but there are subtle correspondences among the cycles determining each aspect of time, nature and life. The true musician knows how to awaken in us that perception of the nature of the world, as well as the emotions connected with the secret rhythms of creation.

Whispers in the Labyrinth

An Account of a Few Days at the Alain Daniélou Foundation at Colle Labirinto, Zagarolo, in June 2015

Shuddhabrata Sengupta: artist, curator and writer with the Raqs Media Collective, Delhi

On a summer afternoon in June this year, looking out from the threshold of the hilltop temple of Fortuna Primigenia in the ancient town of Praeneste, now known as Palestrina, one could make out through the haze the distant shores of the Tyrrhenian Sea.

Even more than two and a half thousand years ago, ships from Egypt bearing goods that had made the long voyage from Indian ports on the Arabian Sea or the Bay of Bengal would have docked somewhere at the edge of the horizon visible from the temple of Fortuna. Perhaps a few enterprising merchants or sailors, salty lascars seeking adventure, would have crossed the Latin plains, climbed Praeneste’s hill, and paid their homage to the Goddess of Fortune. Perhaps they would even recognize resonances between sounds from the hot plains of the Deccan and the humid east-Indian delta and the Latin words they encountered at Praeneste. Those speech forms told of horses, rivers, and a love of drink and song – traces and residues of the movements of the Indo-European speech world across mountains, seas and rivers. Between my own Bengali, my English and the French and Italian around me, these were the continuing traces and residues of my possible ancestors. Perhaps a voyager, distant in space and time, had sat exactly where I was sitting, and wondered about fortunes, voyages and the labyrinthine destinies unleashed by the human desire to wander. Perhaps his interlocutor was another young woman called Petra, or the Breton ancestor of a wise Jacques, or the Latin forefather of a charming Riccardo. They would certainly have quaffed wine, traded stories, laughed and made promises to each other, and heard each other sing.

Petra Lanza, from the Foundation for Indo-European Dialogue (Alain Daniélou Foundation) my companion on that afternoon, who told me about Fortuna and her oracle, had driven me up from Colle Labirinto at Zagorolo to Palestrina. As we looked at potsherds, amphorae, gravestones and the fragments of calendars and inscriptions, we did not have to say very much to each other. There is something simple about human presence, the desire to bridge languages and histories, and the fact of so much congealed time that made it possible to hear things between speech and silence.

At the ‘Labyrinth’ at Zagorolo, the house that the Music scholar and Indologist Alain Daniélou had built with his friend and companion Jacques Cloarec, this was deepened by song. Hearing Ustad Aminuddin Dagar sing, mid-stream, in the middle of conversation, was to be shaken into an awareness of what music does to our bodies, and what it has been doing for thousands of years.

To witness Monsieur Cloareq reminisce about his ancestral Breton customs, or about Daniélou’s particular obsessions with specific forms of music was to access a passion that was both other-worldly in the best sense of the word, and also fully grounded in a very concrete understanding of what it means to pursue a legacy of dialogue between cultures. This was leavened during my days at Zagarolo by exchanges with the artists Atul and Anju Dodiya about the interweaving of the traces of the earthy, the sensual and the esoteric in the Daniélou Archive.

At the same time, to talk with Riccardo Biadene, (Alain Daniélou Foundation’s Director of Artistic Initiatives) about the work that the Alain Daniélou Foundation has undertaken to extend the understanding and public dissemination of Daniélou’s unique philosophical commitment to the sensory and sensual dimensions of human existence was to witness a delicate orchestration between the sensate and the cerebral.

Through all these encounters, between meals, during walks, around a solstice bonfire in the woods below the house of the Labyrinth, I could sense that the conversation that the Alain Daniélou Foundation seeks to deepen, in homage to the legacy of Alain Daniélou, has a very long history. With the Alain Daniélou Foundation it may also have a profound future. While the political leaders of India and Europe trade weapons, find ways of jointly policing land and sea and put further restrictions on the human imagination, it is initiatives such as the Alain Daniélou Foundation’s that will eventually find ways to restore dialogue between people in the place where it belongs – at the intersection of curiosity, desire and respect.

On my penultimate day at Zagorolo, I had the pleasure and honor of conducting a workshop with young artists and critics, many of whom had made the trip up from Rome, especially for this purpose. At the close of a long day talking with them about the work that I do with my colleagues in the Raqs Media Collective, while talking about why we (Raqs) pay so much attention to the question of translation in our work, I was given a remarkable gift. A participant in the workshop, a scholar of the history and cultures of Bengal, presented an account of an extraordinary document – a sheaf of worn papers wrapped in plastic found in the pocket of a pair of jeans that was part of a heap of clothes found in a boat that was lost, and then found, in the Mediterranean, off the coast of Italy. The boat had been carrying migrants to Europe from Asia and Africa, many of whom may have perished in the course of a difficult voyage. Perhaps that sheaf of papers, inscribed in my language, Bengali, may have belonged to one of them.

The papers were a handmade lexicon – mainly of words of daily usage – translated and transcribed, between Bengali, English and, in some places, Italian. Most of them were about ordinary and basic necessities: food, fruit, water, medical emergencies, shelter, but interspersed amongst them were words for poetry, the universe, love, loss, longing and bliss, as if the bearer had need of bread, but not of bread alone. As if the reader, editor and carrier of this lexicon on rough seas had a need to understand and to make himself/herself understood in the language of love and starlight, some of which did not carry over easily between languages. Sometimes one word required many, and the many needed to be read in tandem, in silence, across and around each other.

Like the makeshift lexicon of a twenty-first century voyager on a rough sea, I think the Alain Daniélou Foundation’s real work lies in navigating what can never be translated but must be understood. This will need many conversations, many whispered and spoken and unspoken attempts to find our way in the labyrinth between histories and cultures.

In speaking with the remarkable individuals at the Alain Daniélou Foundation who carry Alain Danielou’s legacy on, I came to sense that this, at least, was the most important thing that artists and intellectuals can do in a world so riven by much too easy glosses on cultural differences.

It makes me want to return to the Labyrinth, many times.

Published by the Alain Daniélou Foundation.

| Representative Bureau – Paris: 129, rue Saint-Martin F-75004 Paris France Tel: +33 (0)9 50 48 33 60 Fax: +33 (0)9 55 48 33 60 |

Head Office – Lausanne Place du Tunnel, 18 CH-1005 Lausanne Switzerland |

Residence – Rome: Colle Labirinto, 24 00039 Zagarolo, Rome – Italy Tel: (+39) 06 952 4101 Fax: (+39) 06 952 4310 |

You can also find us here

For contributions, please contact: communication@fondationalaindanielou.org

© 2015 – Alain Daniélou Foundation

EDITORIAL DISCLAIMER

The articles published in this Newsletter do not necessarily represent the views and policies of the Alain Daniélou Foundation

and/or its editorial staff, and any such assertion is rejected.

https://www.facebook.com/FondationAlainDanielou

https://www.facebook.com/FondationAlainDanielou https://vimeo.com/fondationalaindanielou

https://vimeo.com/fondationalaindanielou