” The first duty of man is to understand his own nature and the basic elements of his being,

which he must fulfill to the best of his ability “

Alain Daniélou

Index:

- » Alain Daniélou: “Why I am a Hindu”, Adrián Navigante / Sarah Eichner

- » Kāśī – Impressions and remembrances, Adrián Navigante

- » Jacques Vigne: the challenge of spiritual psychology, Alain Daniélou Foundation Intellectual Dialogue

- » The Idea of Recurrence in the Symbolism of the Egg, Sarah Eichner

- » Devī and weapon – Devī as Weapon, Fabrizia Baldissera

- » Alain Daniélou Foundation in India – February / March 2015, Alain Daniélou Foundation Intellectual and Artistic Dialogue

- » Alain Daniélou Foundation Events

Alain Daniélou: “Why I am a Hindu”

Adrián Navigante / Sarah Eichner – Alain Daniélou Foundation Intellectual Dialogue

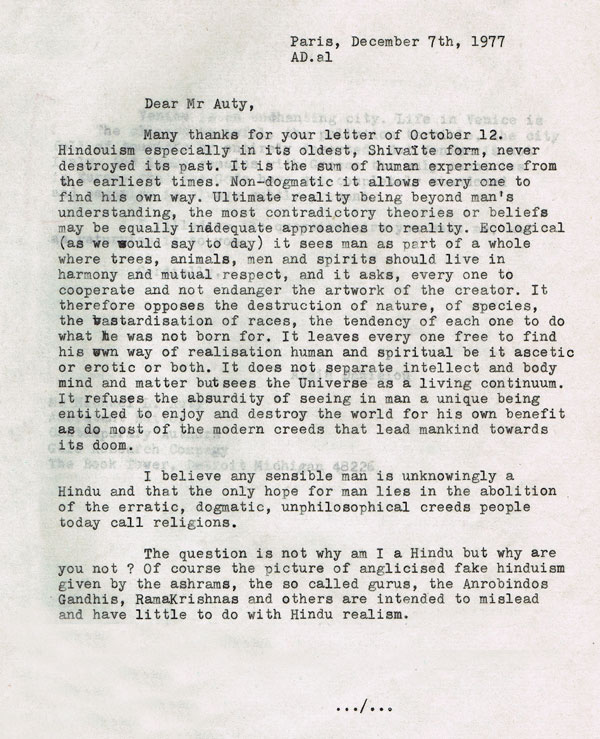

In a letter dated December 7th, 1977, Alain Daniélou explained to the assistant editor of Gale Research Company in Detroit, Michael Auty, what it meant for him to be a Hindu. Auty’s question in his letter to Daniélou on October 12th, 1977, is quite laconic: “What was it that led you to adopt the Hindu religion so firmly as your own?” (1). However, the mere formulation of this question presupposes certain characteristics that might escape the attention of the reader: In the first place, Auty was surprised that Daniélou adopted the Hindu religion: he knew that Daniélou came from a Catholic family, and he took it for granted that the Hindu religion was for him (as for any Westerner) a corpus alienum. In the second place, he assumed that each man has a firm belief in the religion he is identified with – which is not always the case. Last but not least, he supposed that there is something extraordinary, something “out of line” in the decision of a Westerner to adopt the Hindu religion.

Auty’s laconic question reveals the curiosity of a Westerner toward the adoption of a foreign religion. This type of curiosity entails constitutive prejudices leading to the image of Hindu religion many Europeans share. That is perhaps the reason why Daniélou’s answer seems to be articulated on three levels: He presents a kind of brief summary of the Hinduism he experienced – especially during his stay in Benares –, emphasizing the integration of theory and practice and showing that any man with good sense should adopt that way of life:

Hinduism, especially in its oldest, Shivaite form, never destroyed its past. It is the sum of human experience from the earliest times. Non-dogmatic, it allows every one to find his own way. Ultimate reality being beyond man’s understanding, the most contradictory theories or beliefs may be equally inadequate approaches to reality. Ecological (as we should say today), it seems man as part of a whole where trees, animals, men and spirits should live in harmony and mutual respect, and it asks, every one to cooperate and not endanger the artwork of the creator. It therefore opposes the destruction of nature, of species, the bastardisation of races, the tendency of each one to do what he was not born for. It leaves every one free to find his own way of realization, human and spiritual, be it ascetic or erotic or both. It does not separate intellect and body, mind and matter, but sees the Universe as a living continuum. It refuses the absurdity of seeing in man a unique being entitled to enjoy and destroy the world for his own benefit as do most of the modern creeds that lead mankind towards its doom (2).

Precisely in this detailed explanation of the integration of non-dogmatic metaphysics, ecological sensibility, the aesthetic approach to religion and openness to diversity (with the inescapable condition of de-centering human beings from their privileged status as “the crown of creation”), Daniélou turns the question upside down. Viewed from his own perspective, Hinduism should not be a foreign body to anyone; quite the contrary: any suspicion that Hinduism in the form presented by Daniélou might be alien to any human philosophy of life is in itself a sign of intolerance and lack of respect for creation, and it should be reversed in order to avoid catastrophes like those taking place all over the world.

I believe any sensible man is unknowingly a Hindu and that the only hope for man lies in the abolition of the erratic, dogmatic, unphilosophical creeds people today call religions.

The question is not why am I a Hindu, but why are you not? (sic) (3)

Daniélou shows that there is nothing extraordinary in choosing the way of life he saw and learned from Shaivism. What is extraordinary is not to adopt Hinduism, but rather to make oneself a distorted picture of it. How is that possible? In matters of conviction, Daniélou was very intransigent. He thought that the spirit of Hinduism was practically incompatible with the causes many Indians fought for during the British occupation and with the excessive tendency to mysticism, bhakti sentimentalism and the promise of salvation that constitutes the essence of Neo-Hinduism. According to Daniélou, the political ideas of anglicized Indians did not differ greatly from the ideology of colonialism; moreover, the excess of mysticism and outpouring of religious feelings obscured the kind of insight necessary to pierce the veil of human projections when it comes to experiencing reality; furthermore the spiritual message of Neo-Hinduism was tainted by many imports from Christian morals, reintroduced in the interpretation of classical Hindu texts.

Of course the picture of anglicised fake Hinduism given by the ashrams, the so called gurus, the Aurobindos, Gandhis, Ramakrishnas and others are intended to mislead and have little to do with Hindu realism. (4)

Of course, the question remains open as to whether it is fair to make an analogy of Ramakrishna, Gandhi and Aurobindo in the wholly negative terms Daniélou expresses in this letter (and also in some of his books), but in order to even begin to deal with this question, we face a very complex challenge: tracing the heritage of Daniélou’s Shaivism back to its roots.

The roots of Daniélou’s Shaivism are not exactly the roots of what indologists or historians of religion classify as Shaivism. The historical and scholarly determination of a theistic trend within the labyrinthine corpus of Hindu religion misses a very important hermeneutic point in Daniélou’s vision of Shaivism: the conviction (as he declares in his book Shiva and Dionysos) that the experience and knowledge of Hinduism may lead to a profound understanding of our Greco-Roman past (5), in other words, the passage from a particularism inside a religion to a deep structure permeating different religious forms and cultures. Daniélou’s conviction ultimately means that the only difference between Shaivism (in the form of Tantric practices related to a religion of chthonic integration) and Dionysism, Mithraism and other initiatic cults dating back to the pre-Christian era in the history of Western civilization is ultimately a difference between a tradition with continuity and regularity and a tradition interrupted at some point in the course of history. Contrary to the Perennialist verdict that the interruption of transmission is the end of true religiosity, Daniélou believed that an interrupted tradition can be reactivated through analogical experience: If we become familiar (sub specie interioritatis) with Hinduism, the vertical door opens, resurrecting a forgotten past that is much closer to our spirit than we think. In this sense, all Daniélou’s later efforts to get acquainted with the archaic religions of Europe (especially Italy) can be said to stem from his conviction of a trans-Indian substratum (6) susceptible not only to theoretical but also to experiential reconstruction.

Notes:

(1) Michael L. Auty, letter to Alain Daniélou, October 12, 1977 (Archive Daniélou, Zagarolo).

(2) Alain Daniélou. Letter to Michael Audy, December 7, 1977 (Archive Daniélou, Zagarolo). In quoting this letter, some minor modifications in punctuation have been made on the original version for the sake of clarity.

(3) Alain Daniélou. Ibidem.

(4) Alain Daniélou. Ibidem.

(5) Alain Daniélou. Shiva et Dionysos, Paris, Fayard, 1979, p. 57.

(6) “A great civilization whose traces can be found from India to southern Europe, starting from the sixth millennium before our era” (Alain Daniélou. A Brief History of India, Rocherster/Vermont, Inner Traditions, 2003, p. 11).

Kāśī – Impressions and remembrances

Adrián Navigante – Alain Daniélou Foundation Intellectual Dialogue

It was in February of this year that Jacques Cloarec and I arrived in Vārāṇasī in order to explore the area and the general situation around the legendary Alice Boner House at Assi Ghāṭ. It was a sense of familiarity that reached me when we landed in that city, and I wondered how I should answer the typical question people ask you upon arrival in a foreign land: “Are you here for pleasure or for work?” Each one of the tasks at the Alain Daniélou Foundation has for me a twofold dimension: the outer challenge (in this case the project of inaugurating a center in India in the next years) and the inner repercussion of it (the effects an exploration of sacred places may have on us). Both these dimensions are simultaneous; one of them is not privileged over the other. The outer world constrains us to think in goal-oriented terms, but in every action a horizon of experience opens up before us, and it involves much more than what our will dictates for each particular movement. Without an inner dynamic involving a register of emotion, reflection and of course also the elaboration of an unfolding destiny (both individual and collective), the sequence of organized life assigned to us in the course of a certain time cannot be called “experience”. It is a matter of resonance and not of causal chains, that of the inner and outer world, and the distinction, division and even separation of these two spheres is only a subterfuge of limited perception.

Alice Boner House at Assi Ghat. Photo by Adrián Navigante.

Our arrival took place in the evening, and on the way from the airport to Assi Ghāṭ we were already caught up in the vertiginous movement of the city: an endless stream of people, cars, animals and all sorts of shops with sacred objects for sale: weaving, embroidery, stonework, metalwork and woodwork. But this saturation of noise, smell and multitude seemed to drift away when we entered the Alice Boner House. My first feeling was at some point related to that of Alice Boner sixty-eight years earlier, in February 1937, when she settled down in the same place without knowing that she would remain there for the rest of her life: “The multidimensional identity of being rises up. The thousand different individuals and lives […], all hopes, all opportunities, all experiences are aroused and press against each other” (1).

Vārāṇasī is first and foremost concentration. A concentration of every possible element going beyond every frame we might conceive a priori to justify the “usual order of things”. There is a flow that is almost impossible to catch up with or bring down to one’s own rhythm. There are the most difficult challenges to European perception and cognition. What remains today, in the twenty-first century of the Christian era, of that city described by Alain Daniélou in his autobiography, the Vārāṇasī of the 1930s? “Benares is the heart of the Hindu world. It is a sacred and mysterious city, a sanctuary for great scholars, and a meeting place for wandering monks who pass on the traditions of a civilization many thousand years old” (2).

Perhaps the answer is: almost everything, and almost nothing. Even if we avoid a geographical determination of a “center” of Hinduism, we fall back on this word, “heart” (even de-centered), applied to Vārāṇasī just because of what is contained there. I would be tempted to say: what the German philosopher Hegel (who represents the summit of Eurocentric thought) did not understand for the very reason that his “will to synthesis” tried to reduce it from the very beginning and force it into the corset of a specific (logo-centric) way or reasoning: the apparent heterogeneity of natural religion. In fact, natural religion is not confusion of the spirit with natural determinations (3), but the merging of different levels of perception within an intensity core that is difficult to disentangle but dynamically experiential and highly instructive. The consistency and even the overfullness of the contents do not disappear in “a whirl of absolute contingency” (to use Hegel’s verdict on Hindu polytheism) (4). There is, as Daniélou pointed out, a science of limits (5) that should be applied in order to shed light on this world of excessive particularities, in order to really see what is here and there. It is not only a challenge to a somewhat arrogant form of rationality, but also a call from the dark half [kṛṣṇapakṣa]of our own identity construction. The dark half is usually identified with evil, badness, wickedness, all that is to be eliminated, but in reality it is that which enables the light to shine. Each field of visibility is not the effect of pure light (light dazzles and obstructs the visual field, but rather the result of a play of light and darkness) (6).

Vārāṇasī Ghats seen from the Ganga. Photo by Adrián Navigante.

The sacred and the mysterious still exist and co-exist in Vārāṇasī. The Gods never “retired” (as the poet Hölderlin declared emblematically for the West), so they don’t need to be called back and there is also no cultural work of mourning to be fulfilled. Mantras, bhajans, pūjās and saṃskāras intensify, diversify and expand the divine power. The question remains whether all these aspects are still now, as Daniélou said, a sanctuary for great scholars. Are there still knowledgeable people who might be touched by and even immersed in this dimension of religious experience and practice? Are the monks one sees today in this “city of light” similar to the ones Daniélou received almost eighty years ago at Rewa Kothi? (7) Nowadays it is difficult to stumble upon a living repository of oral knowledge and transmission [paraṃparā]; one has to be “qualified” even to take part in an encounter of that nature. Most of the people living in Vārāṇasī today are not qualified, and still less qualified are foreigners (especially those looking desperately for gurus or insisting on mystical experiences without even recognizing the veil of their own psychological projections). Times have changed and the axis of communication is another. There seems to be an unbridgeable gap between the few religiously minded paṇḍits who remain in Vārāṇasī, hidden behind the walls of half-forgotten places and protected by the barrier of language (they speak – even today – no word of English, only Hindi), and the European scholars who analyze the classical culture of India with an aseptic distance from any kind of “anthropological singularity” coming dangerously close to religious mysticism or a regression to mythical consciousness.

Social exclusion and a seemingly unsurpassable disorientation with regard to capacities, functions and tasks became dominant in a city where – for the Indians of the place – the end of Kali Yuga shows ostensible signs: not only the states of the rivers Varuṇā and Asi (Varuṇā highly polluted and narrow, Asi practically dried up and encroached upon) (8) but also that of the social actors who were once bearers of the primordial tradition in the past, the heirs of the ancient rṣis – those who knew both the earthly dimension and the celestial abode of Indra. During my stay I had long talks with a Brahmin who has consciously decided not to teach Sanskrit (or anything related to sanātana dharma) any longer to his sons. When I pointed to the fact that this would be “a crime” from the point of view of orthodox transmission, he replied: “What is the use of orthodoxy without the basis for it? We are at the end of Kali Yuga. The chances of getting a university post or having a place in a temple are getting very narrow for Brahmins, so if my sons don’t study English and go to the United States in order to make a career in anything related to technology and computers, they will be jobless for the rest of their lives”. This man told me sad stories about talented Veda exegetes who get into drugs because they don’t find any way out of the impasses of Kali Yuga: no disciples, no working horizon. They get entangled in social disintegration, but at the same time they accept the logic: it is the ultimate play: Śivalīlā, not only social but also cosmic: the play of dissolution [laya]. In the eyes of a Westerner willing to impose (scientific, technical and political) changes and lead certain processes as if his limited course of action could gain control of the totality of creation, the experience of the twilight of Kali Yuga is the product of a fatalistic world-vision preventing human beings from the adventure of self-determination and freedom. The only world that goes down is that of a classical structure of hierarchical society.

Regardless of those opposed viewpoints, Vārāṇasī is not just one world. It is all possible worlds (with the most heterogeneous elements) together on a relatively small piece of land: from a fake sadhu who wanted to change my name within five minutes and gave me birth for the second time in my life as an initiate (without any instruction, without even receiving a magic formula) to a Western convert capable of reciting hundreds of Vedic verses by heart and fully convinced of the scientific truths encapsulated in Hindu scriptures; from a ravaged homeless defecating on the street beside a sacred cow to the most refined aristocrat well versed in classical and modern (both Hindu and Western) culture; from the worst turmoil of urban pollution to the green oasis of a Theosophical garden at Bhelupur; from the somehow innocent joy of life of the popular layers (remindful of that idealized Roman sub-proletariat depicted by Pasolini) to the gruesome reality of death at the cremation ghāṭs. In spite of all signs of decay, something pushes this city and this people beyond all the typical difficulties of these times. They don’t seem to feel these difficulties the way others do. Do they have the choice? Do we have any choice? But even acceptance of destiny and a soothing dose of fatalism do not prevent some of them from understandable moments of nostalgia. At the exhibition organized by the Alain Daniélou Foundation at the Kriti Gallery on February 14, Jacques Cloarec and I witnessed the faces of old inhabitants of the city when they saw the photographs of Raymond Burnier dating back to the 1930s. Their eyes widened and glittered before the pictures. One of them came up to Jacques in order to express his gratitude for the photos exhibited there: “I saw that Kāśī, the other Kāśī, with my own eyes. Oh, how beautiful, how beautiful she was! A clean place, a quiet place, a sacred body with śakti pouring out of every corner. Alain Daniélou and Raymond Burnier were privileged to live there”. This brief account seems to be a retelling of the Kṛta Yuga, the perfect age (9). Driven by this temporary nostalgia, one might be prone to forget the fact that this man was speaking of a very recent period, the nineteen-thirties. Such a date is, according to the Hindu scriptures, the fifth millennium of the Kali Yuga. It is in this fifth millennium that the twilight of the last yuga begins (10), and we are its “advanced patients”.

“The sacred river, called Mother Ganga”. Photo by Adrián Navigante.

There are of course festivities that serve as a kind of mythical and ritual transfiguration of all negative aspects of the present time. The great night of Shiva [mahāśivarātri]is one of them, and Jacques Cloarec and I arrived in time to witness it: Bael leaves, mantras, fasting, all-night vigil and penances, but also music, dance, bhāṇg and cheerful celebrations at the ghāṭs. Thousands of people make the famous pilgrimage to Kaithi, about twenty-seven kilometers on the north of the city, where there is a little temple devoted to Mārkaṇḍeyamahādeva. Actually Mārkaṇḍeya was a hermit who lived in the forest and during a confrontation with Kāla he received from Shiva the gift of immortality. The addition of mahādeva implies a theological and cosmological step further: while Mārkaṇḍeya was a rṣi, Mārkaṇḍeyamahādeva is seen as an emanation of Shiva. For the Western mentality there is something fascinating and at the same time useless in those masses of people moved from one place to another by the wish to vanquish death: the liturgical repetition of a gesture symbolizing the step over time and its consequences (in Sanskrit kāla means “time” and also “death”), the rupture of the limits of mere individuation, are in the Western world a feeble image of metaphysical illusions. Whenever they are practiced, awareness is not strong enough, the gap between the cold reflection on the process and the blind execution of it cannot be filled. The subtraction of the sacred seems a point of no return, and it is impossible to understand what is going on in such processes. It is precisely through the ambivalent look of Indian people that one can (and perhaps should) gain some insight into ritualistic procedures and divine images. The question is of course whether it is possible to do that in spite of the mechanical verdict on idolatry and superstition being repeated over and over again among rationally educated spirits. If we make it possible, we may discover that the ambivalence has a particular depth: two dimensions with equal values and related consequences (with the impossibility of leaving one of them aside) are no obstruction but rather an opening and an expansion.

During our stay in Vārāṇasī there were very special moments that will certainly remain in our memory. Some of them deserve not only a detailed retelling and a number of sober discussions, but also practical applications for future projects; some others are impossible to mention without transforming their singularity into anecdotic commonplaces. Is there something between these two poles that escapes a final paragraph? Perhaps the story of the middle-sized marble Kālī statue I brought from Vārāṇasī, made by a traditional sculptor who lives and works at Assi Ghāṭ. Late in the evening I was heading back to the Alice Boner House when I saw on the left side of the street an artisanal shop with remarkable stone sculptures of Hanumān, Rāmā, Sarasvāti and Lakṣmī. I decided to take a closer look and, as soon as I put my foot on the balcony leading to the entrance, my attention was caught by a Kālī statue that stood out and filled the room with its presence. No sooner had I become aware of this than the sculptor was there, standing beside me with a beckoning smile. He asked me whether I wanted to see the images of his gurus. We went into an inner room and I recognized Bābā Kīnārām, the great aghorī and saint of the XVIII century, in the middle of the main wall, and beside this image another one of Aghoreśvar Bhagvān Rāmjī, the socially engaged aghorī of the XX century whose teachings reached Europe and the United States. We spoke about the aghorī tradition, which I happened to know relatively well because of a former research project of mine, and in no time what seemed to be an agreeable conversation on Hindu sects turned into something quite earnest. He told me about his meditations, about his refined perception (which is a requisite for sacred art) and the meaning of my visit that night: “You came to take the mother with you. You need and deserve her protection”. He showed me once again the Kālī statue and told me that for many people that image was terrifying, but that he had seen that for me it was beautiful: “You didn’t look at her with profane eyes. Years of spiritual practice activated your saṃskāras and the time is come. I will sculpt the mother for you”.

Saṃskāras are the imprints contained in your unconscious, coming from former lives. With that affirmation of the aghorī sculptor Western readers would say that we enter the realm of fiction. Even if we accept those rules, this kind of encounter remains a very powerful metaphor of a numinous thread permeating the whole of reality and transforming our ordinary perception and cognition of things in the world. That man didn’t know that I had made that kind of practice. Perhaps he had deduced it from my theoretical knowledge of the Aghorīs and of Hindu gurus. Perhaps. But the impact on my soul and the immediate recognition of Kālī as a benevolent mother and not as a gruesome female cannibal revealed a kind of pattern quite alien to analytical interpretations and much closer to disclosures associated with natural forces, abnormal capacities or special ritual enactments. Nothing of that kind happened that night. This man made a very special statue for me and I insisted on paying for it a price doing justice to a whole week of work, carving upon a piece of marble and reciting mantras to accomplish the task in the best possible way. This statue traveled with me thousands of kilometers from Vārāṇasī to Zagarolo, from one very special place to another quite singular place (and fortunately still inconspicuous): Il Labirinto, from which Alain Daniélou wrote: “People claim that the name of Zagarolo comes from Caesariolum, after Caesar, who owned a villa here. For me, however, the word has always evoked Zag, the Cretan name for Zeus. Only much later […]did I discover that Zagarolo and its Labyrinth, along with Praeneste (now called Palestrina) had once been the most sacred site of the ancient world. According to the legend, Aeneas, after escaping from burning Troy, landed his ship at Circeo, fled through the Labyrinth, and finally found shelter beside the Great Goddess who lived in a cavern on the Praenestan Mountain” (11).

I cannot help seeing the Kālī scene linking Vārāṇasī with Zagarolo as a metaphor of Śaktivisiṣṭādvaitadvāda, the integral association between Shiva and Shakti. Numinous metaphors have the characteristic of reenacting the force that is apparently lost with the metaphorical displacement. It is a displacement leading back to a center that never lost the spur of its own expansion.

Water pollution conceived as “the mother’s pain”. Photo by Adrián Navigante.

Notes:

(1) Georgette Boner/ Luitgard Soni/Jayandra Soni (ed.). Alice Boner Diaries, India: 1934-1967, Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass, 1993, p. 237.

(2) Alain Daniélou. The Way to the Labyrinth, New York, New Directions, 1987, p. 133.

(3) Georg Wilhelm Friederich Hegel. Philosophie der Religion (ed. Larsson), II, 1, pp. 11-12.

(4) Hegel, Vorlesungen über die Philosophie der Religion, I. Frankfurt, Suhrkamp,1986, p. 337.

(5) Cf. Alain Daniélou. Approche de l’hindouisme. Paris, Kailash, 2007, p. 42.

(6) In cosmological terms one can speak of the two halves of the world’s egg: white and black, day and night, hot and cold, life and death (cf. Monica Sjöö/ Barbara Mor. The Great Cosmic Mother. San Francisco, Harper & Row, 1987, p. 63).

(7) “Sometimes wandering monks would ask us permission to stay in the lower rooms of the palace, directly facing the Ganges” (Alain Daniélou. The Way to the Labyrinth, p. 126).

(8) According to the Purānic literature, these two rivers were created to protect the city from evil: “Asi” = the sword, and “Varuṇā” or “Varaṇā” = the averter. They are said to be the veins of the metaphorical body of the city, and that is the reason why their present state is interpreted as a sign of advanced decadence.

(9) The name of the yugas is borrowed from the names of the “throws” in the game of dice. In the case of kṛta the sign of perfection has to do with the throw turning up the side with four pips, a real accomplishment, as the root of the verb kṛ (= to accomplish) indicates.

(10) Cf. Alain Daniélou’s chronology of the Kali Yuga in the second appendix of While the Gods Play (Rochester, Inner Traditions, 1987, pp. 263-266, especially p. 266).

(11) Alain Daniélou. The Way to the Labyrinth, p. 232.

Jacques Vigne: the challenge of spiritual psychology

Alain Daniélou Foundation Intellectual Dialogue

Jacques Vigne

Next month the India Europe Foundation for New Dialogues (Alain Daniélou Foundation) will welcome Jacques Vigne for the first time at the Labyrinth in Zagarolo. This French psychiatrist with thirty years of experience in India has gone beyond the frame of Western psychology in his understanding and treatment of the “maladies of the human soul”. Having learned yoga and vedānta directly from traditional Indian sources and being receptive both to the discoveries of Western science and to the transformation of Indian spirituality in modern times, he works permanently on an expansive approach focused on the task of filling the gap between Western knowledge of psychic and neurological processes and the Eastern approach to the ultimate reality of the soul (closely related to the spiritual aim of “Self-realization”).

According to Jacques Vigne, India has its own “traditional psychology”, the basis of which is the search for perfection and liberation from all existential chains [mukti]. This psychology has barely been explored “as such”, because in order to understand it, the transpersonal implications of the field must be borne in mind – something that seems to contradict the main principles of modern psychology in the Western culture. If one succeeds in exploring this field, the notion of many so-called “pathologies” will change – beginning with the very opposition between “normal” and “pathological” and continuing with the understanding of very important pathologies like psychosis (can psychosis be considered a form of mysticism?) or depression (can depression be taken as the beginning of spiritual growth?). Jacques Vigne is convinced that if therapists remain prisoners of their own interpretational framework, they will be unable to go beyond the existing barrier between the mental and the spiritual sphere. At the same time, preserving the intellectual reservoir of Western psychology and neurology enables him to discern the question of mental processes with a certain thoroughness and analytical clarity that is sometimes necessary to rule out spurious elements interfering with the practice of yoga and meditation.

Referring to his own experience, Jacques Vigne speaks of an “inner India”. The interiority he refers to is the inner space ranging from mental (subliminal and unconscious) processes to the so-called Self (dynamically understood in the sense of the upaniṣadic relationship ayam ātmā brahman). The challenge of a comparative spiritual psychology means understanding that our widely accepted (Western) normality is – from the point of view of a “spiritually developed being” – pathological and needs to be cured. The (unseen) pathology consists of different patterns of behavior, the conditionings of which create both individual and collective suffering. The way from psychology to spirituality is a path of awareness and awakening. It is precisely his experience of this path that Jacques Vigne will share with us at the Labyrinth next May.

In order to introduce the person and work of Jacques Vigne a little more deeply, we present the following extract from an interview and part of a text of his on psychology and meditation.

From Psychiatry to Meditation: Interview with Jacques Vigne by Alain Chevillat (abridged) (1)

With your twofold course of studies (on the one hand yoga and meditation and on the other psychiatry), what difference do you see in the approach and results of these two ways of dealing with the spirit?

In India we say that the guru has to teach the adhikāri, that is, those who are ready to receive such teachings, those who have a fundamental balance enabling them to practice sādhanā, the ascetic path of spiritual development and self-realization. In this sense, there is an ostensible difference of level between the object of psychopathology and the object of yoga. But of course we always find overlapping zones, especially if we bear in mind simple yoga techniques that may be very beneficial for people suffering from psychological disturbances. On the other hand, knowledge of psychology can be very useful in treating mental problems of a subtle nature that are far from being serious pathologies. Such problems are often present in people with an interest in spirituality, that is, persons following a certain form of spirituality or at least wishing to follow one. In this context it is important to know what we mean by psychology.

Can psychiatry really help?

The spiritual master who really attains realization does not need Western psychology, but an ordinary spiritual teacher situated within the frame of his own tradition on a lower level than that of self-realization may reap some benefit from studying Western psychology. Indeed, there are things that psychology can reveal to him. If he doesn’t know them and his own spiritual experience does not enable him to perceive them, he may feel impotent in the face of a pathological case and abandon the patient (as a result of fear) instead of helping him.

There is a concept that you develop in your book “Elements of Spiritual Psychology” [Élements de psychologie spirituelle, Paris 1993]that particularly appeals to me: the concept of “normosis”. What does it really mean?

During my stay in India I was able to see Western society from a certain distance and perceive some global aspects that were inaccessible to me when I was submerged in it. What happened in my case can be compared to that of a huge building: when we stand with our nose against the wall, we cannot see its whole size. As an idea, “normosis” means recognizing psychological good sense. When we are in contact with certain people, we often see clearly that they have not experienced fulfilment, that they have no spiritual development, that they are very basic and even primitive. However, we cannot say that they are “pathological”, since they function quite normally in society and everyday life, and they don’t get entangled in any serious problems. In such cases I speak of “normosis”, because in my opinion a really normal human being is somebody who evolves. Somebody incapable of evolving, of questioning himself and progressing, somebody who is, as it were, fixated with certain patterns revealing pathological elements, is an example of what I would call “normosis”.

Is “normosis” a widely spread phenomenon?

It is a cumbersome phenomenon in Indian society if we consider modes of behavior, since Indians have very precise norms that can lead to “normosis” in the absence of any dynamic evolution of habits. From this point of view, we might say that there is more freedom in French society. However, on a level of spiritual choices, we must say that “normosis” is fairly strong in French society. For fifteen centuries, the predominant idea was “outside the church there is no salvation”, whereas today there is a void that secularism and governmental directives cannot fill – simply because that is not their function. When all’s said and done, “normosis” is not dependency with regard to society, but above all dependency with regard to oneself.

Let’s go back to the time of your arrival in India. Which aspects of that culture attracted your interest? It is true that you had already practiced yoga and meditation, but moving to India is quite another thing. How did you end up earning your daily bread in that country?

When I finished my traineeship in psychiatry in Algeria, I pondered upon my future. I thought that if I were to continue my work there, I would end up entangled in a hospital practice and afterward in a medical practice. For this reason I thought that if I wanted to get away, I shouldn’t wait any longer. I sold a little car I had in order to get some cash and went to India for six months to see whether I could find a spiritual teacher in Yogic therapy. That appealed to me. I made the acquaintance of a disciple of Ānandamayī called Vijayānanda, who was himself a French doctor and had come to India thirty years earlier. When I returned to France, I said to myself, “I have to go back to India with a scholarship”. At the time I had already heard of a research scholarship provided by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. I applied for a scholarship and got it, so within one year I was back in India.

Is your relationship with India purely external and professional? Do you go there just to carry out research or does something in you vibrate when you are there?

Actually I went to India in order to embark on a sādhanā and be close to people who know that path. Of course I love India, but in my case it was not love at first sight. There are people who arrive in India and feel that they have always lived there. What I personally appreciate about my situation in India is the freedom I have and the proximity of people with profound experience of spiritual practice. I love the open-mindedness of so many in a country that remains mostly quite traditional, as well as the Indian mentality, which is not so busy and overcharged as ours, and of course their interest in perceiving religious and spiritual ideas – although many people in contemporary India don’t know their own culture very well.

I made many spiritual contacts in India because I was preparing my book The Master and the Therapist [Le maître et le thérapeute, Paris 1991], which took me five years of ashram visits and conversations with disciples and gurus. In the first three years I didn’t write a single page; I was just being introduced into Hinduism, to Indology and Indian languages. It was during the subsequent two years that I wrote the book.

How would you define yourself today? As a yogi, or rather as a writer?

Since the term “yogi” can have – as in the Bhagavad Gītā – the sense of “being realized”, I would avoid any definition of “yogi” applied to me personally. Rather than a yogi, I am a sādhaka, that is someone who carries out regular spiritual practice. I am also a writer in my lost or regained time. It all depends on which point of view we adopt.

Occasionally I am even a psychiatrist, as I was in the context of a three-week experience back in 1993, when I saw on the TV news that an earthquake in Mahārāstra had left between ten and twenty thousand casualties. I decided to go there because I knew that rescue parties are full of surgeons and general practitioners but they lack psychiatrists. I was immediately incorporated into a hospital with between 100 and 120 earthquake victims, all people who had lost half or three-quarters of their family. In order to deal with those people I used the knowledge I had acquired about mourning, and I noticed that, seven years after interrupting my practice as a psychiatrist, I was still able to work as such in a foreign context faced with such a catastrophe. It also comforted me that, thanks to my meditation practice, I was able to establish direct contact with people who were very different from me. Of the victims of that earthquake, 40 to 50 % were illiterate and didn’t know anything about psychology or psychiatry. It was necessary not only to speak their language (in that case Hindi), but also the spiritual language of the heart. When somebody loses at least three-quarters of his family in a matter of seconds, spiritual questions become much more relevant than any psychological detail. So I was able to establish a relationship with them, both through words and beyond words. This was made possible by my meditation experience and the time I had spent with yogis – a time of silence rather than words.

With regard to the future, do you see yourself as a hermit in India?

I certainly want to spend a long period as a hermit because I feel like it and believe I am prepared for it. When I return to India this time, I should like to go on a retreat of six full months, since it is the least I can do to make my basis more solid. During the three or four months I spend each year in France, I communicate a lot, and I see I need to limit this kind of interaction and intersperse it with long periods of silence. I feel drawn to the life of a hermit and would like to experience it in order to attain a certain spiritual level. However, I don’t believe (unlike Christian monks) in permanent vows. I think that long retreats are very useful, but devoting oneself to the cloister seems to me too institutional and too juridical.

A practical work on anxiety and emotions through the observation of sensations (2)

by Jacques Vigne

Introductory remarks

I have been living in India for twenty years, and go on regular retreats to a hermitage in the Himalayas. During this long period of time I have been able to discover many ways of practicing introspection. Those wishing to develop a good basis for meditation need a very clear idea of the relationship between body, mind and emotions. In this respect the methods inspired by vipassanā, the clear inner vision of Buddhists, are very useful. Yoga, too, can be a great help in experiencing the subtle body and the correspondence it establishes between the different parts of the organism and the functioning of the psyche.

All this is essentially linked to the opening of the energy channels, constituting an important phase in the development of meditative yoga. Alain Daniélou perceived this when he translated into French the founding text for this type of practice: the Śiva-Svarodaya. This text expounds a relaxation technique that in itself has a very profound anti-stress effect. Indeed, it is another domain in which traditional practices come close to modern discoveries.

Neutralization of bodily sensations: Yoga as a path to equanimity

The Bhagavad Gītā offers one proper definition of yoga: samatvaṃ yoga ucyate; yoga is equanimity. In a more technical fashion, we might translate samatvam as “equalization”, and in so doing we come very close to what was accomplished by Buddha in observing the act of breathing, that is, vipassanā. Through this observation we bring those areas of the body affected by stress (which are most intensely felt) and those free from stress (which are neglected by our bodily attention) into harmony. A logical way of proceeding – expounded by S. N. Goenka and a Burmese line of meditation to which I also belong – is to go through each part of your whole body observing its sensations without letting your attention pass too quickly from one part of your body to the other only to dissipate itself afterward. A quick change of attention to parts of the body is typical of our usual mental behavior during relaxation without mind control. In fact, it is the concatenation of sensations that forms the basis of our emotional reactions, depriving us of inner freedom. If we manage to control these chains of sensation from the very beginning, the serpent of disturbing emotions is cut into small pieces and can no longer damage us. The Nāga cobra may continue to hiss, but it won’t bite.

Let’s suppose that we observe the sole of the left foot and in doing so a feeling of tension crops up, associated with an emotional remembrance of anger. The habitual catenation will entail the unconscious propagation of that tension toward the right foot, and then toward the hands, which will clench as if they were about to deliver a punch, and finally to the jaws and neck. All this happens without our realizing it, since our mind is projected toward an external cause that is assumed to have given rise to the feeling of anger. If, on the contrary, we observe the tension on the sole of the left foot in an objective manner, it remains there and thus we automatically avoid the disagreeable sensation (as we usually do), a sensation that tends to increase until it reaches a peak, and afterwards will decrease and finally dissolve. When it dissolves, a harmonious sensation remains and the corresponding area will be integrated by it. If we get used to perceiving this process behind all sensations and in all bodily parts, we come close to nirvāna consciousness, or to the background canvas of the Self that “illuminates by means of its own light” (svaprakāśa, according to Vedānta thought).

From a practical point of view, it suffices to wait until a sensation emerges from one moment to the other in some part of the body. This is an attitude of pure observation, the quality of which increases when the body is fully relaxed (as when overtaken by sleepiness, but in reality very attentive), like a cat pretending to slumber in front of the mouse-hole and catching the mouse the moment it comes out. This technique can also be compared to the behavior of an Eskimo when he makes a hole in the ice-field and waits until the fish comes in order to catch it. It is certainly not forbidden to use particular means to awaken the sensation of a specific part of the body. This can render the method less arid for beginners, who will naturally regard the absence of sensation as the main obstacle to the meditation process. One possibility is to imagine that the air we breathe comes in and goes out through the skin, as through a very thin handkerchief; that it rekindles an ember that was about to die out, and that from the ensuing fire emerges the part of the body we are observing. We can also imagine that we rub any bodily area we choose, or that someone else rubs it. A real Shiatsu or acupressure session is only possible with the aid of our own consciousness.

Through such practice we train ourselves to gain direct access to equanimity. In order to verify the equanimity we have attained, it is useful to remember facial expression and breathing. Indeed, from the very moment a sensation appears in any part of the body, our face reacts, as though its expression were confirming the type of sensation going on: “I love”, “I don’t love”, or “I am indifferent”. This reaction does not always happen immediately, and sometimes it is very subtle and almost imperceptible.

Analysis of contrary emotions

Another variant of vipassanā enables us to refine our analysis of contrary emotions. This is something I like to teach in my meditation courses, since I think it helps beginners understand better and control their emotions, thus responding to frequent and urgent demands. We know that, in each part of the body, the muscles function in an agonistic-antagonistic manner. For example, it is because the triceps extend that the biceps can bend the arm by contracting. Without this antagonistic coordination, tetanization would occur, without any movement. In the same way, sensations are bodily emplaced in terms of agonistic-antagonistic poles. If we resort once again to the example of the sole of the left foot related to the feeling of anger and concentrate on the antagonistic area (the back of the foot and the sensation it provokes), we will perceive that this area is connected to a feeling of relaxation, peace and forgiveness. This applies to all parts of the body, so we can considerably refine our analysis of emotions through direct perception of sensations. We have to bear in mind that the lower areas of the body are statistically related to disturbing emotions, for example if we decide to observe any part of the body corresponding to this area, the related emotions (manifesting themselves in the form of sensations) are fear, anger and desire. It is only in the second phase that the complementary sub-areas – corresponding to reassuring emotions like appeasement – are perceived.

If a disturbing emotion is particularly repetitive, we can choose to rememorate it at first in the whole body, and afterwards make an analysis of each of the body’s parts. In so doing, we will realize that in many of these areas, disturbing emotions stimulate only one area at the cost of the complementary zone, which remains insensitive – as if it were blind to stimuli. If we relax the stimulated area and make sensations slip toward the blind area, we will become aware that the emotional associations correspond to the contrary emotion. It is a mistake to think that emotional confusion may overwhelm us. In fact, such a thing affects only certain parts of the body, and if we take a deeper look at it, we will see that only certain sub-parts of the related body part are actually affected. The idea behind all this is to make a very precise psycho-emotional diagnosis for each part of the body in order to obtain a very precise therapeutic effect on the same part. Of course, overall positive thinking is always a help: it is always good to say “I am no longer going to get angry; from now on I am going to stay calm”. However, this type of persuasive method does not always turn out to be as effective as one may wish, since in such a situation we are like a surgeon who wishes to make a biopsy of a tumor without knowing exactly where it is.

Notes:

(1) This interview was made for the French Association Terre du Ciel in 1994. Although Jacques Vigne has made enormous spiritual progress since then, it is worth reproducing some fundamental lines of thought still present in his work and his way of living today. For the complete interview in French, see Jacques Vigne, L’Inde intérieure, Gordes 2007, pp. 148-155.

(2) This text is quite recent and shows us a mature Jacques Vigne with ample experience of India. For a more complete treatment of the subject of this text, see Jacques Vigne, Meditazione, emozioni e corpo cosciente, Milano 2013.

The Idea of Recurrence in the Symbolism of the Egg

Sarah Eichner – Alain Daniélou Foundation Intellectual Dialogue

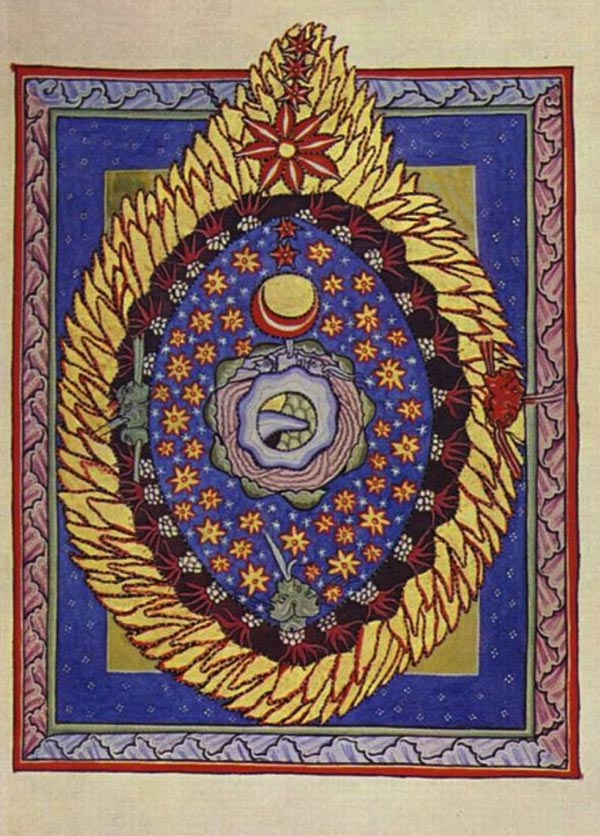

“One could describe the principle of the world as a boundary, a curve that encircles the universe and forms the cosmic egg.” (Alain Daniélou).

“The universe appears to man as an egg divided in two halves: the earth and the sky. The egg is considered the origin of life. In it the male and the female principles are reunited.” (Alain Daniélou).

“Afterwards I saw an enormous and dark entity like an egg.” With these words Hildegard introduces her cosmic vision. The egg-shaped entity represents the totality of the cosmos with the earth in its center.(Hildegard von Bingen: Scivias, p. 40)

The idea of recurrence or rebirth can be found in different cultures and religions. If one takes a universalistic perspective, this idea should not be seen as a rebirth of a single being, but rather as a cyclic renewal of life (on a cosmic level) in its totality: its creative powers, patterns and various life forms. It is not centered on any individual phenomenon, but rather on wholeness as an interconnected plurality, insofar as each form of life at each moment of its very (in-)existence remains integrated in a encompassing cosmic continuity, the begin and end of which is unfathomable. This wholeness constitutes in itself a circle, the sign of its completeness. As Daniélou points out, totality is very often represented in the form of an egg: “The universe appears to man as an egg” (1).

According to the religious scholar Mircea Eliade, the idea of renewal, new beginning or re-creation can be traced back to the concept of birth, and this concept in turn to the notion of cosmic creation. In the symbol of the egg, the revival of vegetation – and together with it the revival of the whole cosmic being – is announced: “each return of spring represents the cosmogony, every sign of the resurrection of vegetation is equivalent to a total manifestation of the universe” (2). The coming and the beginning of spring do not simply refer to its natural manifestation (as a cosmic phenomenon). It is at the same time a symbol of the resurrection of life in its wholeness (that is, in its beginning and its cyclic repetition, in which the beginning is evoked once and again). In the rituals of spring and newyear as well as their mythic, ritual and symbolic elements, the drama of creation manifests itself with different degrees of intensity (3). Among such elements announcing the coming spring and expressing the idea of a renewal of life, the symbol of the cosmic egg has a prominent position. This symbol refers to the cosmic creation, which it announces and evokes. This is why it is very often related to symbols and emblems of the renewal of nature and vegetation, which are in turn connected with the myth of periodic creation (4). The latter appears in the ritual use of eggs, for example in European culture at New Year and Easter: “The image of the egg as a symbol of resurrection, the periodical return of life, is perpetuated in the colored eggs of Easter” (5).

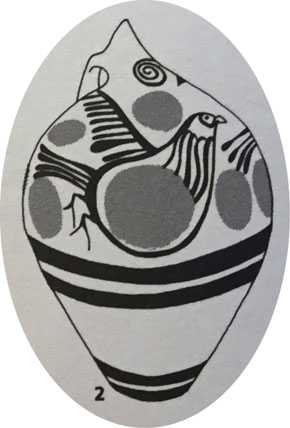

The archeologist Marija Gimbutas affirms that Easter is a Christianization of spring rituals of regeneration belonging to archaic religions. In the Slavic and Baltic countries, eggs were colorfully painted with swirls, spirals, snakes, half-moons and vegetation symbols and given to each member of the family. In this way, the coming of spring was celebrated (6). In order to guarantee the renewal of vegetation, eggs were put into the ploughed earth. This was taken as an offering to the chthonic deities (7). Eggs had also special significance in burial ceremonies as religious objects for quick regeneration. This association is already attested in the early Neolithic period, with burial vessels in the form of an egg. According to Marija Gimbutas, these vessels symbolize the womb of the goddess, from which life is born again. The importance of egg-like patterns (such as circles, ovals and ellipses) as religious symbols can be traced even as far back as the upper Paleolithic period: in Magdalenian art, circles and ovals are engraved on female buttocks and bull images (8). To the same context belongs a myth widely known in archaic societies according to which a cosmic egg was laid by a sacred water- or fire-bird.

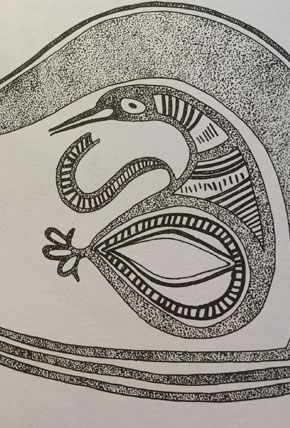

“Late Minoan vase, with a bird carrying an egg –

usually red – in her belly.”

Source: Marija Gimbutas,

The Language of the Goddess, p. 214

“Water bird with sprouting egg in its belly.”

Source: Marija Gimbutas,

The Language of the Goddess, p. 216

In addition to this, the egg relates to the element water and the bull as symbols of life regenerators, as well as to symbols of becoming such as spirals, crosses and sprouting germs, all of which point to the energy inherent in the egg.

“An egg forming whirling or spiral compositions.”

Source: Marija Gimbutas, The Language of the Goddess, p. 218

Prehistoric art shows that, in the system of belief that Marija Gimbutas called “old Europe” (9), the egg stands for becoming, regeneration and new creation (10).

Mircea Eliade emphasized the fact that the symbol of the egg has not so much to do with birth as with rebirth, that is, with a return, an imitation or repetition of the birth of the cosmos (11). The cyclic or periodic element makes each recurrence a re-turn. Return and recurrence, life and death form an inseparable whole in the general transformation process of all life forms. In the Book of Changes [Yijing]the place where this process is accomplished is kun, the earth, which at the same time appears as the place of birth, transformation and death. Light (as the offspring of life) is born in the womb of the earth, and after its full manifestation (the blossom of life) returns to it. The close and inextricable relationship between life and death, or recurrence and return, is symbolized in the signs of the Yijing in a paradigmatic way. In the context of the Yijing, kun, the earth, is without solidity. It is an empty field:![]() . The first level of transformation (the first line of the hexagram) shows the solidification and appearance of something. The sign that results from it is fu, recurrence

. The first level of transformation (the first line of the hexagram) shows the solidification and appearance of something. The sign that results from it is fu, recurrence ![]() . What returns on the first line (below) is light, the life-forms created by the earth. Each further instance of solidification can be seen as a gradual growth of life-forms, and this growth reaches its summit with the sign t’ien,

. What returns on the first line (below) is light, the life-forms created by the earth. Each further instance of solidification can be seen as a gradual growth of life-forms, and this growth reaches its summit with the sign t’ien, ![]() , which stands for heaven. Already, this sees the movement of returning and the process of deconstruction, which in the context of the Yijing is expressed by means of bo, the sign of fragmentation

, which stands for heaven. Already, this sees the movement of returning and the process of deconstruction, which in the context of the Yijing is expressed by means of bo, the sign of fragmentation ![]() . This fragmentation is the last level of transformation of the earth (last line, above). When the last line is fragmented, a complete return to the empty field of the earth takes place. The process of becoming

. This fragmentation is the last level of transformation of the earth (last line, above). When the last line is fragmented, a complete return to the empty field of the earth takes place. The process of becoming ![]() and vanishing

and vanishing ![]() is fulfilled within the earth

is fulfilled within the earth ![]() and as a general transformation of it. Each return means death (an inversion of the process), and at the same time is accompanied by the recurrence (as its complement): “Once the cosmic gate is opened, and closed again, the beings stream out of it, the beings stream into it: that is called transformation.” (12) In the Yijing the birth of the cosmos is traditionally interpreted as the result of the union of heaven and earth, that is, the impregnation or insemination of the earth by the power of heaven. However, if we take into account the structure of the signs indicated above, heaven can be seen as the first manifestation of the earth: the light that is born from the telluric womb. This light represents the plurality and diversity of life-forms, in turn created by the earth.

and as a general transformation of it. Each return means death (an inversion of the process), and at the same time is accompanied by the recurrence (as its complement): “Once the cosmic gate is opened, and closed again, the beings stream out of it, the beings stream into it: that is called transformation.” (12) In the Yijing the birth of the cosmos is traditionally interpreted as the result of the union of heaven and earth, that is, the impregnation or insemination of the earth by the power of heaven. However, if we take into account the structure of the signs indicated above, heaven can be seen as the first manifestation of the earth: the light that is born from the telluric womb. This light represents the plurality and diversity of life-forms, in turn created by the earth.

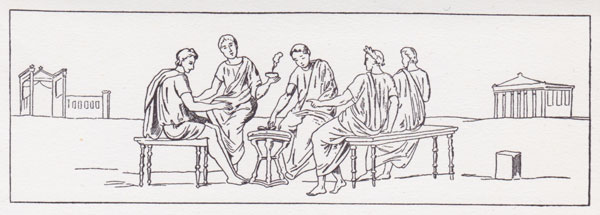

“Youths speaking about the meaning of the egg in the Bacchic mysteries.”

Inscription on a grave at Villa Pamphili, Rome.

Source: J. J. Bachofen, Mutterrecht und Urreligion, p. 23

In his essay Versuch über die Gräbersymbolik der Alten, the anthropologist Johann Jakob Bachofen comes to a similar conclusion when he interprets the eggs in a Pamphilian grave picture (which are painted black and white) as a symbol of the female material substrate of all things, the arche genesos: “The material substrate of things that generates all life out of itself includes the whole field of becoming, both arising and vanishing. It carries simultaneously the dimension of light and shadow of nature in itself” (13). This opposition expressed by the contrast of bright and somber colors points to the permanent passage from darkness to light, from death to life. It shows the “telluric creation” (14) as an infinite fluctuation between two complementary poles. And as far as the creative principle is concerned, it can only be active in relation to the principle of destruction; death can be seen as the precondition of life: every “telluric organism” (15) is nothing but an effect of this combined action. The black and white pattern of the egg is not only a symbol of union (or hierosgamos) of heaven and earth, the female and male principles (as Daniélou points out), but the confluence of contraries within the all-encompassing female nature principle, the arche genesos as mother of the universe: she is the primordial dwelling-place of heaven and earth, darkness and light, the stream of arising, existing and vanishing, of all creatures of telluric life including gods, humans, animals and plants. This has to do with nothing less than the ultimate correlation of life and death, the complementary play of opposites and their coinciding in the female source of life. According to Bachofen, the female material substrate of all things played an important role in the Bacchic mysteries. In fact, he regards the egg in the mystery cults as a symbol leading initiation back to the female source of life, the Great Mother, from whom Dionysos Bimetor also originated: “The phallic god tending to fertilize matter is not the first instance; he himself originates from the darkness of the mother’s womb and finds his way into light. His relation to female matter is that of a son to his mother […]. This phallic god cannot be thought of as separate from the female material principle. Matter as mother, which gave birth to him, now becomes his consort” (16).

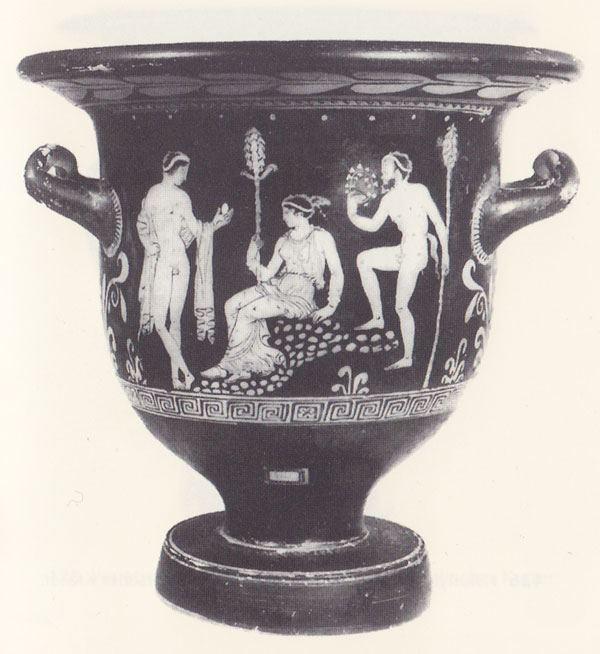

“Youth with Egg before ‘Ariadne’.” Apulian Crater. Lecce, Museo Provinciale.

Source: Karl Kerényi, Dionysos, picture 124

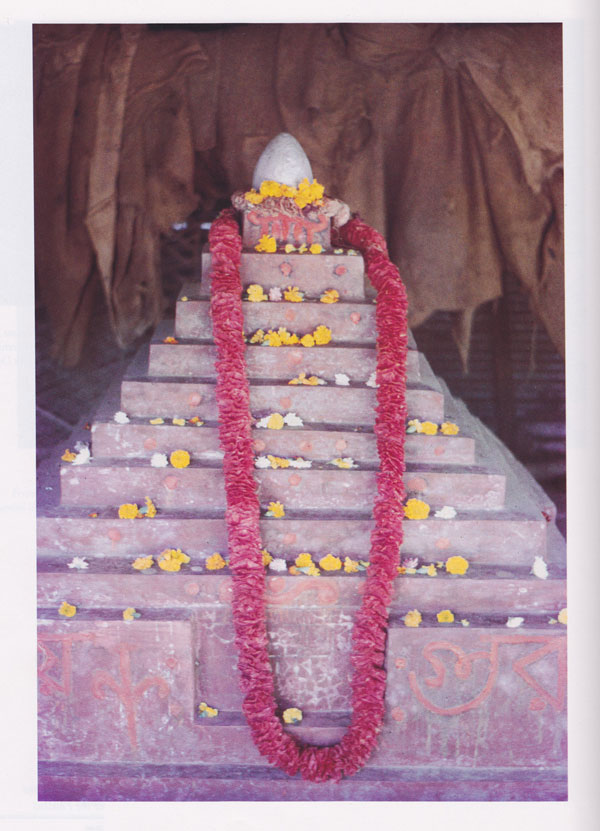

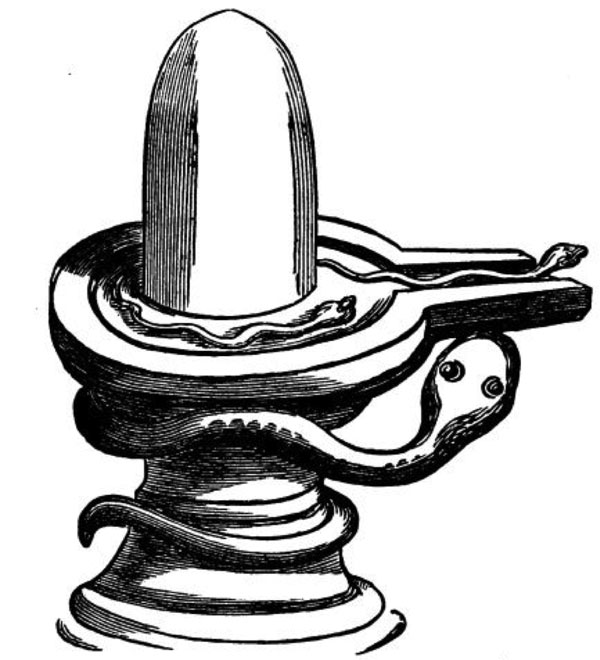

In his book The Phallus Alain Daniélou writes that the egg is also a sign [lingam]belonging to Shiva, and thus a symbol of male creative power: “In the Tantra, the usual symbol for Shiva is always a phallus, but in the Purānas, there is often reference to the form of an egg as a lingam” (17). The oval (egg-like) shape of the Lingam represents the universe. The symbol of the lingam can be seen as a (phallic) representation of ‘Lord Shiva’: his manifest form as an object of worship and adoration.

“India: Shiva lingam garlanded with offerings of flowers and substances.”

Bengal. Photographed by Nik Douglas.

Source: Alain Daniélou, The Phallus, p. 39

In an old Indian legend about the origin of the lingam and yoni cult, a picture of a lotus flower is shown, at the center of which a triangle – as symbol of the cosmic female organ – appears. Issuing from the triangle stands a membrum virile, a lingam, in the form of a cone. This lingam has three cortex-layers, which produce the gods Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. After this process has taken place, there remains only the stem at the center of the triangle, possession of which is from now on taken by Shiva. In the same picture, Shiva appears as the bearer of the phallus/lingam. Not only in this legend, but also in many iconographic representations of the Shaivite and Tantric traditions, the basis upon which the lingam stands is the yoni.

“Representation of a lingam and yoni.”

Bengal. Photographed by Nik Douglas.

Source: J. M. Wheeler, Essays on Phallic Worship and Other Curious Rites and Customs, Figure 1

This basis is not only a support of the lingam, but is also the source from which the phallus/lingam arises (as the sun, light or life itself, arises from the womb of the Earth). This does not of course invalidate or question the importance of the symbolism of sexual union in the sense of a regeneration of original completeness. In fact, sexual resonance is the Dionysian law par excellence, realised through union [gamos]. The same is true of Shiva and Shakti: the former is identified with the male creative principle and therefore with the phallus, the latter is associated with the female creative principle, the yoni: “It is in the union of the lingam and the yoni that the divine, the power to create, becomes visible […]. Procreation is impossible without such a union, and divine manifestation is equally so without its cosmic equivalent” (18).

However, the sexual resonance expressed by the hierosgamos, is not the only sense of the relation manifested in this symbol: initially the relation of the lingam to the yoni is that of a son to his mother; only in the second instance is the relation meant to be that of a couple. This has nothing to do with any hierarchic structure. What becomes manifest in this symbol is the togetherness of the opposites on one common ground that generates all opposites equiprimordially. The symbolism of the mother or the tendency to denote this source as female is due to its life-giving force, its creative power. It constantly gives birth to all life and bears every single being equally, that is, without differences. All beings are born from it and return to it in an infinite circle: “The spirit of the valley never dies. It is called the Mystic Vagina. The doorway of the Mystic Vagina – it is called the root of Heaven and Earth. Continuous and persistent, it works without effort” (19).

Notes:

(1) Alain Daniélou. The Phallus: Sacred Symbol of Man’s Creative Power, Rochester/Vermont, Inner Traditions, 1995, p. 37.

(2) Mircea Eliade. Patterns in Comparative Religion, University of Nebraska Press, 1996, p. 412.

(3) Cf. Mircea Eliade. Ibidem, p. 413.

(4) Cf. Mircea Eliade. Ibidem, p. 416.

(5) Alain Daniélou: The Phallus, p. 39.

(6) Cf. Marija Gimbutas: The Language of the Goddess, London 2001, p. 213.

(7) Cf. Mircea Eliade: Patterns in Comparative Religion, p. 418.

(8) Cf. Marija Gimbutas: The Language of the Goddess, p. 213.

(9) Marija Gimbutas, a Lithuanian archelogist, contributed to major advances in the understanding of Bronze Age Indo-European migrations. Author of 22 books and more than 200 articles, she directed five excavations in Europe. Gimbutas controversial later theory concerns to a goddess-centered belief system underlying East European Neolithic communities. Gimbutas claims that the non-belligerent matrifocal societies stretching from the Balkans to Crete were later destroyed by patriarchal Indo-European invaders in a westward expansion between 4000 and 3500 B.C.E from their original homeland. Cf.: Michael York, in: The Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature Volume I, Bron R. Taylor, Jeffrey Kaplan (ed.), London 2008, p. 696.

(10) Cf. Marija Gimbutas: The Language of the Goddess, p. 218.

(11) Mircea Eliade. Patterns in Comparative Religion, p. 419.

(12) Vgl. Rainald Simon: Yijing, Buch der Wandlungen, Reclam 2013.

(13) Johan Jakob Bachofen: Mutterrecht und Urreligion, Stuttgart, 1984, p. 25f., my translation.

(14) Bachofen: Mutterrecht, p. 25.

(15) Bachofen: Mutterrecht, p. 26.

(16) Bachofen: Mutterrecht und Urreligion, p. 30., my translation.

(17) Daniélou: The Phallus, p. 37.

(18) Daniélou: The Phallus, p. 23.

(19) Laozi: Daodejing, Das Buch vom Weg und seiner Wirkung, Passus 6, my translation.

Devī and weapon – Devī as Weapon

Fabrizia Baldissera

Associate Professor of Sanskrit at the University of Florence

In the innumerable small goddess shrines that dot the Indian landscape, one is struck by the frequent substitution of the Goddess’s portrait, mūrti, by a sword, a spear, a trident or a simple stick (1). I interpret these weapons as the double of the Goddess, also because in the key text that best exalts her might, Devīmāhātmya (2), ‘The glorification of Devī’, the Goddess is indeed the secret weapon of the male gods in their fight against the demons. In this narrative the demons obtained a boon that made them invulnerable to male gods: the latter then created the Goddess by concentrating all their fiery/luminous energies, tejas, and each of them equipped her with his own special weapon, which she brandished in her multiple arms. Her might thus far surpasses that of each god, as she has the force de frappe that identifies her with a truly unconventional weapon, dealing mass destruction. This text describes her first appearance ‘as if a thousand suns had all risen at once (3)’, which immediately struck me for its similarity with the majestic/terrific manifestation of Viṣṇu to Arjuna in Bhagavadgītā 11. 12 (4). In a late text, Tripurārahasya ‘The secret of Tripurā’ (composed between the 10th and 17th centuries CE), Goddess Tripurā manifests herself from the sacrificial fire, generating a great sound and a blinding light that together stun even the gods (chap. 51). Here the explosion ‘as if a thousand suns …’ is accompanied by a mighty thunderclap, a bloodcurdling noise which, in other texts, is her battle cry.

The seven stones of the little goddesses, with the main Devī and the trident.

Southern Rajasthan. Photo by Stephen Roach.

A survey of different goddess images in literature and in the visual arts reveals that an inherent ambiguity surrounds the figure of the Indian Goddess. She appears beautiful or horrific, in an ugra, ‘terrifying’, or saumya, ‘beneficent’, attitude (5). Her thousand epithets mirror these dichotomies. In both modes, however, she carries unusual weapons (6). In the oldest texts, the Vedas (starting 12th century BCE), there are few goddess figures who, as compared to the male gods, appear of limited importance, while a couple of them have sinister connotations. Her oldest visual representations, however, hail from an earlier period, that of the Hindu Valley culture (3.000 BCE), if the figurine flanked by two animals or two plants found on seals is indeed a goddess. India still has an enormous number of goddesses, ranging from simple aniconic representations such as stones or weapons to fully fledged anthropomorphic icons, mūrti, the latter usually found in temples.

Literature displays a similar polarity. In her fierce aspect, especially in the epics, the Goddess betrays a primitive tribal nature that sometimes surfaces even in her later puranic myths (7). Throughout the different texts she gradually seems to develop into a ‘civilised’ warrior, poised to fight demons who threaten the order of the worlds (8). The Indian warrior is a kṣatriya, ‘land protector’, a member of the landed gentry, to which kings belong (9). The Goddess figure undergoes several changes both in the texts and in visual portraits that show her fighting in different manners, using different weapons. After the Hindu Valley seals, the next found female deity is a much later coin of the Kuṣāṇa king Kaniṣka (whose accession is dated between 78 and 144 CE) showing on the reverse ‘the figure of a goddess with a lunar crescent, seated full face on a lion crouching left, and the goddess appears to have a noose and a sceptre (10)’. The reverse of coins of Candragupta I of the Gupta dynasty (about 325 CE) shows a goddess riding a tiger or a lion. These images might have been influenced by the Hellenistic Cybele as seen on a medallion excavated from Aï Khanoum, in Bhaktria.

After the Vedas, the most relevant texts describing the Goddess are the Mahābhārata, ‘The Great [War] of the Bhārata’ (composed between the 4th century BCE and the 4th CE), the Harivaṁśa, ‘Hari’s Lineage’, (circa 4th century CE), the Skandapurāṇa (whose earliest layer dates to the 6th century CE), and the Devīmāhātmya (second half of the 8th century CE (11).)

Hymns sung to her in the Mahābhārata (12) and Harivaṁśa portray her as the wild, dark-skinned deity adored by the tribals Śabara, Pulinda and Barbāras. In the Skandapurāṇa the Goddess has already undergone some transformation towards the ethos of the ‘noble warrior’, as noticed by Yokochi 2004. Whereas in Harivaṁśa she carries only a trident and a sword, in the Skandapurāṇa the wild goddess Vindhyavāsinī, ‘The inhabitant of the Vindhya mountains’, in full warrior panoply rides in a chariot drawn by lions and covered with a white royal umbrella (13). She wears guards on her arms and fingers, a breastplate, and two quivers. This is a step towards her gentrification, finally accomplished in the Devīmāhātmya, which pulls together the different strands of local goddess traditions to unify them as a single powerful Goddess figure (14). Here we have the ultimate representation of the Warrior Goddess, whom the male gods resort to for help, and whom they empower through their fiery energy and by giving her their specific weapons. Some of her oldest tribal traits are however still apparent, especially in the goddess figures she creates to assist her in battle. The terrific Kālī she emanates turns into the uncanny Cāmuṇḍā (15), who sports as a weapon a human femur (the khaṭvāṅga, an ancient attribute of Lord Śiva), and, what is more, with her fangs and formidable jaws, she devours the demonic hordes together with their horse-drawn chariots and war elephants.

As the supreme warrior who protects the territory, the Goddess is also the guardian of the fighting power of weapons.

A contemporary rendering of the armed Devī from a festival image in Gujarat.

Photo by Stephen Roach

One of the two hymns sung in her honour in the Mahābhārata occur at the time of the lustratio by fire (16) of the heroes’ weapons, which might had become rusty during the rainy season, when military campaigns were suspended. Several purāṇas narrate such ceremony during the festival of Navarātrī, ‘Nine nights [in honour of the Goddess]’. In this rite, called nirañjana, the weapons are polished and the war-animals of the king are honoured with jewels and a parade. Such rites today are still performed in many of the ex-kingly states of India, in the presence of members of the ex-royal households. Here the Goddess who ‘gives back their fire to weapons [after the monsoon]’ appears to be the tutelary deity who both protects and legitimates a royal dynasty, especially through her special favour in battle. This is sometimes shown in legends that see a goddess giving a magical sword to a hero, as in many stories of the 11th century CE Kathāsaritsāgara (17),‘The Ocean of Stories’, in the strangest of which the hero is enjoined by his pregnant wife to cut open her belly and grasp the embryo. Dismayed, he tries to refuse, but the ‘woman’ is adamant: when the hero gets hold of the embryo, it is immediately transformed into a wonderful sword (5.3.145 ff.) In another story it is quite clear that the sword offered by the Goddess is the double of its wielder: when the sword is damaged, the hero becomes hopelessly sick (9.2.155-165.) The Goddess’ sword was interpreted as both a sign of her favour and of royal legitimation even in more recent times, as well as in historical/legendary accounts about the initiators of dynasties, such as the first king of Bastar. When Wrangal in the 15th century CE was overrun by Muslim forces, Goddess Danteśvarī appeared in the shape of a sword (18) to Prince Annamdeo of the Kākatīya dynasty of Wrangal, and led him to Bastar, where he became king. Similar stories are also told, from the 12th to the 17th centuries CE, of Rajasthani, Orissan or south Indian dynasts. An interesting account is given about the great Maratha military leader Shivaji of the 17th century CE, believed to have received an invincible sword from an ally through the favour of his tutelary goddess Bhavānī (19). Conversely, when a king, usually during the Goddess’s festival, or before entering battle, comes to see the deity in her temple, whether in the royal palace or in the wilderness, he carries his sword sheathed, to show that he is coming in peace (20).

of the fighting power of weapons.

Devī and her symbol, the trident, in Kumbalgarh, Rajasthan.

Photo by Stephen Roach.

At times, parts of the Goddess’s body itself could be seen as weapons, as in some early sculptures of the Kuṣāṇa period, in which she wrestles with the buffalo demon using her bare hands. She twists his neck with her arm, while upending him by his tail with her other hand. It is only in the middle of the Gupta epoch (5th century CE) that a new iconographic type appears, in which she fights with a spear (21), and has a lion as her mount. This is the Mahiṣāsuramardinī (22) icon, which later enjoyed wide dissemination throughout India, and was the model of the later Devīmāhātmya description. Here the Goddess thrusts her spear into the demon’s neck (a bit like a bull-fighter does even now with his sword, or the picador with his spear). She now fights after jumping on him and standing on his back, and here emerges another of her peculiarities: the contact with her body is salvific, so the touch of her foot saves the demon, who becomes her devotee, as described in Bāṇa’s Caṇḍīśataka, ‘The hundred [stanzas] on the Fierce One’, of the 8th century CE.

In several works the Goddess is also represented with a large number of arms – twenty-eight in the Agnipurāṇa (composed between the 9th and 11th centuries CE), each wielding a different weapon. In an Agnipurāṇa incantation against periodic fever (Chap. 134), Goddess Cāmuṇḍā is exhorted thus: ‘Oṁ, cut and pierce through with thy trident, kill with thy thunder, strike with thy club, cleave with thy quoit, Oṁ, pierce with thy spear, bite with thy teeth, fell with thy karṇika (an ear-shaped arrow), attack with thy mace’ (23).

In the same text, as well as in the Kathāsaritsāgara and in Tripurārahasya the Goddess weapon is magic. This can either paralyze an army, create uncanny beings, or obstruct any aperture or passage. In the Kathāsaritsāgara (14. 3-106) goddess Gaurī imparts her devotee Gaurīmuṇḍa a magical spell called Gaurīvidyā, ‘Gaurī-science’, which appears in person and stupefies a whole army of wizards (24). In the Tripurārahasya, the Goddess magically produces mongooses from her mouth, to counteract snakes produced by the demons. In a subsequent passage she employs three unusual weapons. In her child-like form, Bālāmbā, she throws against the demon Bhaṇḍa a five-pointed arrow, that rests like a hand on the demon’s head (25). The next one is the Paśupatāstra, ‘the missile’, astra, of Śiva Paśupata, ‘Lord of the uninitiated’, a very powerful weapon of mass destruction which in the Mahābhārata wrought havoc in an enemy camp. Finally with the Kāmeśāstra, ‘the weapon of the conqueror of Kāma’ (26), Tripurā turns Bhaṇḍa to ashes with his capital city and causes pralaya, ‘universal dissolution’ (27).