Alain Daniélou

INDIAN AND WESTERN MUSIC (PART II)

This is the second part of Alain Daniélou’s article on Indian and Western music published in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1949. Daniélou deals with the language and the systems of music, Greek and Indian music history, as well as some important questions of musical technique. Considered from Daniélou’s standpoint, the distinction between “India” and “the West” in matters of musical theory is mainly expressed in the conceptual opposition between “modal” and “harmonic” music. The text has been edited from Daniélou’s notes in the Zagarolo archives and contains some minor modifications.

Alain Daniélou playing the piano at Zagarolo. Photo by Jacques Cloarec.

Alain Daniélou playing the piano at Zagarolo. Photo by Jacques Cloarec.Indian History

No cyclic or melodic literature – Among the earlier works on music, we find – as could be expected – no literature regarding the Mongolian pentatonic which had always its centre outside India. It should be remembered that this Mongolian cyclic pentatonic has nothing to do with the pentatonic forms of the basic rāgas in the Śaiva system. Further the melodic system has left to my knowledge no important theoretical literature. A scrutiny of Tantric documents might, however, reveal some valuable elements.

Dravidian and Aryan texts – As regards the Dravidian and Aryan modal systems we possess many documents of the greatest value and antiquity. Generally speaking, we can observe that the earliest theory of Dravidian music, as found in Sanskrit texts, is represented by the Śaiva school whose main expounder is, after Śiva himself, Nandikeśvara. Besides these, other important names are those of Śārdūla, Pārvatī, Jamadagni, Bhṛṅgī, Vighneśa, Kīrtidhara, Rāvana, etc., and probably the musical theory found in the earlier Purāṇas, the Vāyu Purāṇa, the Mārkandeya Purāṇa, as well as such works as the Gītālamkara which is attributed to Bharata but is the work of a Bharata distinct from the presumed author of the Natya Sastra. The Nātya Śāstra itself is a compilation probably dating from the beginning of the Christian era and expounding mainly the theory derived from the Gāndharva Veda. The Gītālamkara, on the other hand, is a purely Śaiva work and all its classifications are of a different and very original kind.

It is very difficult to date the earliest Śaiva texts on music. It is also difficult to ascertain their original language. But the musical theory they expound and especially the use of certain technical terms or instruments can help us to be quite affirmative about their antiquity independently of all linguistic considerations.

Tamil and Greek sources – The Tamil epic, the Śilappadikāram, which belongs to the second century, has important passages referring to the theory of music and musical instruments, and is thus a precious help in dating contemporary works.

Vedic music – I have neither authority nor sufficient knowledge to enter into the question of the origin of the so-called Aryan civilization. So far as music is concerned, we find from the earliest Vedic period a constant use of music and instruments. The Ṛg Veda mentions some wind and string instruments as well as drums. The Sāma Veda was chanted, and there were theoretical treatises and Śikṣās explaining all the technical peculiarities of this chant. Later, under the name of Gāndharva Veda, appeared a vast literature on music, its philosophy and its technique. The number of early theorists of Aryan music whose names are known is considerable, but very few works have survived although a certain number of quotations from these in later works are sufficient to determine with confidence the nature of the system.

Among the names of the early writers of music some are quite celebrated – Agastya, Kāśyapa, Aṅgirasa, Vasiṣṭha, Yājñavalkya, Yaṣṭika, Añjaneya and many others.

Narada – A strange figure creates a sort of link between the two schools – Dravidian and Aryan, or Śaiva and Vedic -, and that is Nārada. There are fragments of his work belonging to either school. It is true that all the available works attributed to Nārada are of different periods. But there must have been an original Nārada and he is claimed by both sides.

Bharata – Similarly Bharata appears as an indefinite entity. But this is a different case. The word ‘Bharata’ simply meant a performing artist and the treatises referring to dance and music naturally came to be known by that word. We know of at least four Bharatas who are called Ādi Bharata or Bharata Muni, author of the original Nātya Śāstra. But there are also Nandi Bharata, Arjuna Bharata, Mataṅga Bharata and others. The existing Nātya Śāstra is probably a compilation of extracts from several of these original sources made during the Buddhist age.

Sanskrit literature on music – The vast Sanskrit literature on the theory, the philosophy and the technique of music, which lies so sadly neglected and unpublished in the libraries of India, represents a system which has no rival in the world so far, and from which modern Western theory would have much to learn. It is not easy, however, to know how far this rich Sanskrit literature is indebted to earlier literature. There is little doubt that in the process of the Aryanization of India much earlier literature was translated or adapted in Sanskrit while the originals were lost. This is certainly true of parts of Purāṇic literature. And this explains why we often find very ancient books written in late Sanskrit, a fact that has led unwary scholars to discard them without due consideration.

The earliest theory of Dravidian music, as found in Sanskrit texts, is represented by the Śaiva school whose main expounder is, after Śiva himself, Nandikeśvara.

Nandikeśvara’s surviving works – A careful research would, however, allow us to identify and recover many ancient works. For example, I was fortunate enough to be able to identify a valuable fragment of Nandikeśvara’s work which lay anonymously in the Bikaner library. This short fragment explains the theory of music on the basis of the Maheśvara sutra in terms very similar to the explanation of the theory of language by Nandikeśvara on the same basis in a work known as Nandikeśvara Kāśikā, which is sometimes incorporated in the Mahābhāṣya.

Western History

Origins of Western music – The early musical theory of Europe appears, so far, rather cloudy. This may be due to the lack of comprehensible documents, but also to the fact that most Western research on history was done at a time when historians were genuinely unaware of the importance and antiquity of Indian civilization. This led them usually to interpret as a spontaneous and natural growth cultural developments that were in fact built with remains of older elements with their roots in the East.

Western modal music – Seen in the light of what we know now of the early cultures in Europe and India, we are bound to come to very parallel developments: first a musical culture spreading to Egypt, Crete, Italy and probably further north. Then came a succession of invasions by more barbarous people who gradually adopted the ways, manners and instruments of the conquered countries. This assimilation was, however, less complete in Europe than it was in India and therefore it is again from the East that, periodically, came new influences and developments to shape the culture of ancient Europe. Whatever we know of the musical system and instruments of the Greeks leaves little doubt in this respect and so too is the case for the instruments still found in those countries where druidical culture lasted longer. The survival of the biniou of Brittany and the bagpipe of Scotland is particularly interesting since the presence of the drone pipe proves, without a doubt, that the music of these people was at one time often played on melodic lines where the drone serves no essential purpose. It could surely not have evolved out of a melodic form of music. Harmonically it is monstrous.

The stability of the mode absolutely requires a drone, a permanent sounding of the tonic: this is neither essential nor desirable in any other system.

Survival of ancient systems in Europe – In England, today, there are very few people, even among music students, who are aware that Scottish bagpipe music belongs to a system entirely different from Western harmony. It is a system akin to Arab and Indian music, quite unsuited for Western orchestra and instruments. Similar is the case of Hungarian and some branches of Norwegian popular music. Further, there are definite traces of pentatonic music of the Chinese family all along the Atlantic coast from Spain to the north of Scotland. But what is really amusing is that Scottish or Hungarian music lovers may well get infuriated if told that their music is still different from what is now in fashion in Europe, and in fact belongs to an Eastern system.

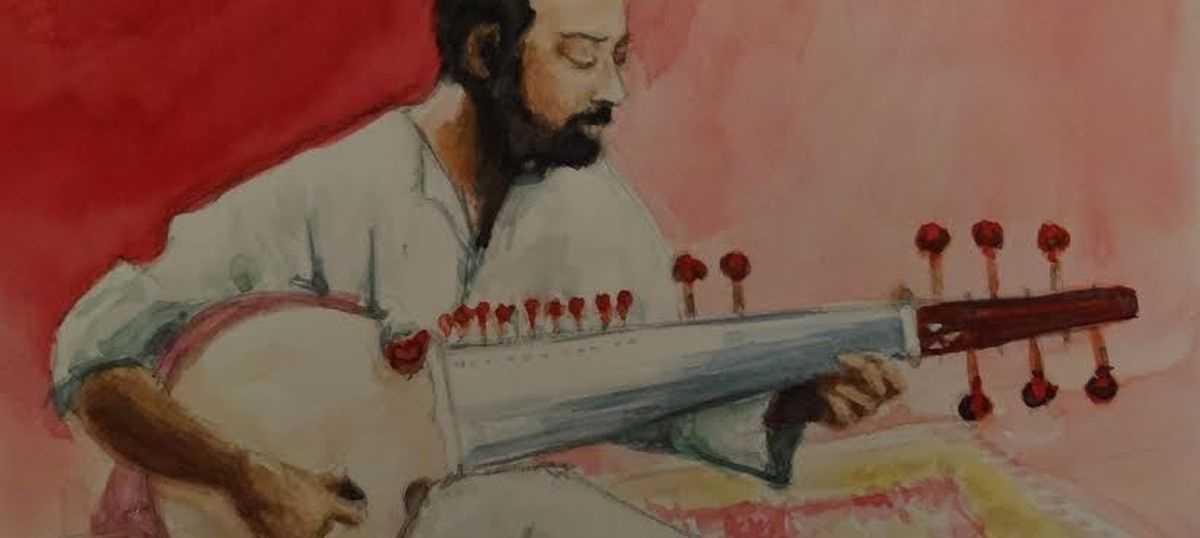

Juan Moreno Moya: Portrait of the Sarod player Kalyan Mukherjea, an undisputed authority on Indian classical music.

Juan Moreno Moya: Portrait of the Sarod player Kalyan Mukherjea, an undisputed authority on Indian classical music.I remember a celebrated Hungarian violinist, to whom I had spoken of the great interest I took in modal forms surviving in Hungarian folk music, who, with undisguised anger, answered me sharply that ‘there is nothing in Hungarian music which does not belong to the Western diatonic system’.

Greek theory – In Europe the earliest writings on the theory of music that have come down to us are those of the Greeks. These refer basically to a modal system of the Indian family. But certain elements of cyclic music had found their way into musical theory, probably through Turco-Mongol channels giving rise to the Pythagorean scale which so strangely perverted and confused the writings of the Greek authors.

Mediaeval music – After the Greeks we know very little about the state of music in the West except a little church music, the modes of which were imported from Byzantium in the sixth century by Pope Gregory. The picture of Europe at the end of the Middle Ages shows us a mixture of modal and melodic systems. Arab music exerted a profound influence on the southern countries, an influence that still predominates in Spain and south-eastern Europe. On the other hand, the earlier modal systems remained well preserved in northern countries and the traveling minstrels used instruments which show that modal music was at a rather high level of technical development.

Beginnings of Polyphony – It is in this context that polyphonic music began to develop. How it first started is not quite certain, but it probably owes its origin to some Mongolian influence through eastern Christendom, for the superposition of voices is a natural development in cyclic music, not so in modal music.

At first, polyphony was limited to adding to the main melody a second voice, making slight variations. This had a rather interesting effect and, although it weakens the modal expression, it became quite popular as a novelty in congregational singing.

Gradually this new fashion developed, and a more complex counterpoint was evolved, first with two voices and drone, then with 3 and 4 voices.

Now, the modal expression, the Raga, cannot exist where there are several voices at different pitches. The mutual relation between these different notes, which form themselves in chords, creates new expressions that annihilate the concentrated expression of the modal note. To the modal musician, polyphony is extremely distressing, rather like several people speaking together so that you cannot follow any one of them. In fact the new polyphonic system must have been at first a fashion, a game of amateurs against which all the classical musicians fought desperately. But musicians were poor and of low standing. They could do nothing against the whims of society. Meanwhile the new fashion found great favour among the aristocracy. It was easy, new, amusing and finally it completely defeated the old music. Thus Europe found itself in the fifteenth century with a new musical toy still primitive and undeveloped, while the old musical culture was quickly dying out.

Parallel with modern India – We can easily understand what happened by comparisons with Indian music today. Through the desire of fashion we see the development of an orchestral form of music that corresponds to no musical necessity whatever, which is ruinous for the music native to the land and utterly distressing to all sensitive ears. But this is a unique opportunity for unmusical and ignorant youngsters to declare themselves the geniuses of a new art, and take the bread out of the mouth of India’s great ustads. It is merely a fashion. It has, we may hope, no future. But it may well ruin entirely the music of India, leaving this country with but a vulgar copy of the cheapest Western music, such as what we can find in Egypt, Malaya, the Philippines, etc., today.

In Europe the tragedy was great. But it was final, and out of the ruin of mediaeval music a new art had to develop.

Development of Harmonic music – Due to their ingenuity and patience the musicians finally managed to produce out of the harmonic system very remarkable works of art. It should, however, be remembered that, from the point of view of the theory of music, the possibilities of harmonic music are considerably lower than those of other systems – that is, the range of emotions and ideas that harmonic music can express is far less than what modal music can account for. Westerners, however, supplemented the limited possibilities of the music itself through endless research in the field of instrumental colouring, and also through contrasts and oddities of sound relations. It led to the creation of the modern orchestra – a marvellous achievement of exquisite workmanship and infinite labour in which the total quality of wonderfully built instruments is perfectly balanced in a most melodious whole. Yet we find this great sound producing machine strangely inadequate to express certain kinds of emotions.

Western music is essentially sensuous. It aims at creating a pleasurable atmosphere where vague visions and sentiments gently blend into one another. There it profoundly differs from modal music which on the contrary tends to create a one-pointed concentration where the tonal value of voices and instruments becomes insignificant since the mind is entirely taken away into an abstract world of ideas and visions.

The particular tendencies of both systems are well shown by the fact that the themes of Western music are mostly themes of passion, while Indian music, though depicting all types of emotions, always ultimately leads to some form of contemplation.

I have no intention of belittling the great work of Western music. The man of genius can express himself through any medium, and each medium has its own possibilities. The advantage of writing music further enables us to preserve the inspired moments of great musicians. But we should keep in mind that an Indian ustad on his single instrument can transport us into a diversity of visions, into a depth of emotion very much subtler than that produced by the thunder or murmur of the orchestra with its elaborate instruments.

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, epitome of European classical music. Source: Wikidata.org.

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, epitome of European classical music. Source: Wikidata.org.Statistical possibilities – This is not a question of talent: I do not mean to say that the Indian musician is necessarily more subtle than the Western. It is purely a question of statistical possibilities. Contrary to common belief, the variety of sound relations possible in modal music is very much greater than those possible in harmonic music. Perceptible sound-relations in a system where the tonic changes are far less numerous than in a system where the tonic is fixed. And differences of intervals which are not appreciable in a harmonic system become wonderfully intense in an oblique movement by relation to a fixed tonic.

Relative number of chords and ragas – The poverty of possible combinations in the harmonic form of music has finally led Western music to a sort of dead-end, and to a decline from which it may not easily emerge unless it deeply alters its basis. This is because the whole of Western music is built around 12 or 15 different chords which have been now used and re-used in every conceivable way.

On the other hand, although each raga corresponds to a definitely distinct mood, the number of theoretically possible ragas is immense. Should a man try to play each of the possible ragas once for five minutes, even playing without rest or food for a hundred years, he would not see the end of his attempt.

Decay in Indian music – There is no doubt that a certain degree of paralysis has arrived in Indian Music. It cannot be said that it has degenerated because the great ustads of today still have a remarkable level of technique and expression. But progress has stopped through the loss of theoretical knowledge, since the musicians no longer know Sanskrit in which all the theoretical works were written.

Remedy – The revival and development of Indian music will depend on a return to classical forms and a study of classical musical literature whether directly in Sanskrit or through adequate modern translations.

In Europe the earliest writings on the theory of music that have come down to us are those of the Greeks. These refer basically to a modal system of the Indian family.

It is in this field that irresponsible improvisations should be discouraged if we wish to avoid in India the musical tragedy that has overtaken modern Egypt, Malaysia and the South Sea islands. It is to be hoped that learned societies may take an interest in encouraging a sane study of the country’s priceless heritage and may encourage true learning to protect the nation’s cultural assets against attacks by irresponsible reformers and unqualified amateurs, always ready to start risky experiments without due regard for classical values.

Technique

Musical translation – We have seen that music, like language, is a means of expressing ideas and emotions through the medium of coordinated sounds. Just as different families of languages offer different possibilities of expression and rarely have exact equivalents, so too the different systems of music offer different possibilities and cover different fields of expression.

In comparing the two musical systems now prevailing in India and Europe, we will discover that practically not one of their features can be transferred from one to the other. It might seem easy enough to take a simple Indian song, a Tagore song for example, note it down and harmonize it as if it were a Western melody. This is a simple process. But we find that this melody, although it may sound quite lovely, will not convey to the Western hearer anything resembling the feeling conveyed by the Bengali song. In the context of a new system the melody has completely changed its meaning.

Equivalent sounds may convey distinct ideas – I once saw a cartoon representing an American soldier looking sentimentally at a French girl and saying ‘May we’ and she answers ‘Mais oui’. The only difference is that, in French, ‘Mais oui’ means ‘of course yes’. By changing language, the very same sounds have acquired a completely different meaning. If we want to convey the same idea in different musical systems we shall be faced with a very similar phenomenon. We cannot make use of common features.

We have to translate, that is, first analyse the meaning clearly, then try to express it through another medium. To harmonize Indian songs according to Western harmonic rules will usually not make good Western songs and will convey to the Western hearers no idea whatever of what the songs means to Indian ears. This does not mean that it is not possible to write certain Indian melodies in Western notation. It is moreover possible to write accompaniments for modal music which can be played on Western instruments. But for this one has to follow the rules of modal polyphony which is very different from harmony. Even then the song so arranged will convey only part of its expression to the Western hearer. He will require some training to become familiar with hearing this new form of music, which has been only slightly adapted so as not to shock his outward conception of what music should sound like. We should not forget that, according to the perfect definition of Sanskrit grammarians, ideas are conveyed through sounds by a process of ‘recognition’, not by a direct perception, and we cannot understand a language or a word we do not already know.

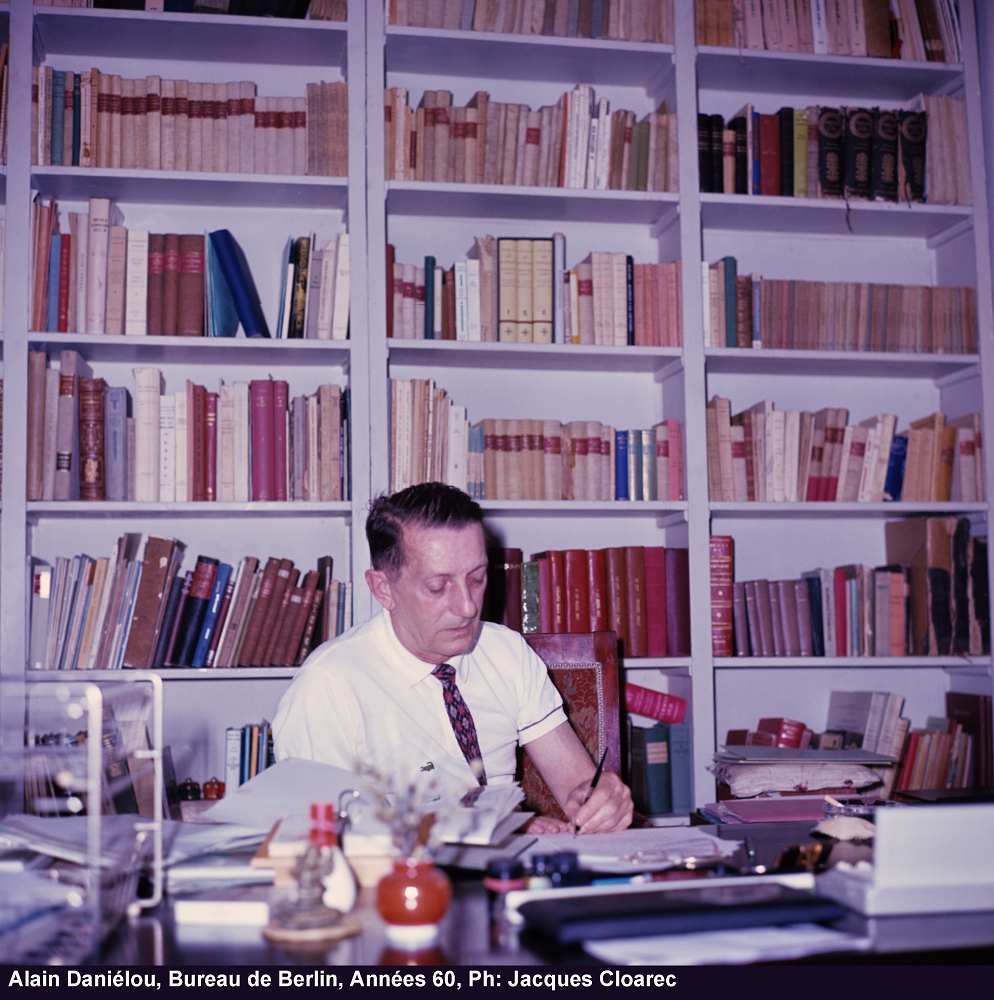

Alain Daniélou at his office of the Institute for Comparative Musicology in Berlin, Photo Jacques Cloarec.

Alain Daniélou at his office of the Institute for Comparative Musicology in Berlin, Photo Jacques Cloarec.Difference in ways of hearing – As we have seen, the main difference between modal and harmonic music lies in how it is heard. We believe that we hear music with our ears and that we instinctively find the sounds pleasant or unpleasant. But it is not so. We do not hear music with our ears although we hear it through our ears. We hear music with our memory. When we hear a sentence we have to remember all its successive sounds so that the last sound may reveal to us the idea. This is a commonplace saying of Sanskrit grammar.

Training of memory – In music a similar rule applies, and we may not be surprised to find that by training our memory to record a particular succession of sounds rather than another we may come to hear, that is to get from the music, a meaning, an expression, that is completely different. We shall thus see that modal and harmonic music are in fact based on two different ways of hearing, so that to understand both one has to be musically bilingual.

Musical bi-lingualism – We can easily see that an Indian listens to Western music with his own mental habit, following the shape of the melody as if it were a horizontal development independent of chords, and he is sure to find it meaningless, disorderly and discordant.

On the other hand, when the Westerner listens to Indian music, he is unable to grasp its continuity, and he finds it bodiless and insignificant.

The mixing of systems – It is not particularly difficult to train oneself to hear both systems, but one must study both forms of music quite independently. Raga and harmony are quite incompatible and cannot co-exist. Those who pretend to mix both systems are, from the point of view of music, irresponsible illiterates. Although one may have one’s own preferences, it would be wrong to believe that both these musical systems cannot offer great possibilities of expression. One may choose either. But there is no compromise, no appeasement possible between them. Harmony has entirely ruined the modal music of ancient Europe and will destroy any modal music on which it is superimposed. Official and other encouragements given nowadays to modern Indian orchestras amount to nothing but an attempt at cultural suicide. There is no valuable contribution to world music that India could make by trying to blend her own with Western music. The possibilities of harmonic music are comparatively limited and have been exploited to their utmost, so much so that Western musicians are now desperately looking for new musical forms to revitalize their music.

Potentials of Modal Music – We have seen that modal music, on the other hand, offers almost infinite possibilities of which only a small fragment is utilized in present-day Indian music. It is to be hoped that the effort of Indian performers and technicians may be turned towards research in this field, in which they already have realized such magnificent achievements, rather than wasting their energies in the no-man’s-land of hybrid music.

Music and National Spirit – A question comes naturally to our mind. The development of Indian music is linked to a particular conception of life, to a particular culture and civilization. The Indian listener comes to hear music with a mind different from that of the Westerner. The idea of an underlying Divinity pervades all activities of Indian life and all the arts are conceived as processes of identification with some higher state of being. Religion, philosophy, music are all here based on common principles and cannot be separated from one another.

The Western hearer is very different. His attitude is that of a moralist. He does right actions and is then entitled to a place in paradise. He stands on his right. Knowledge to him has little to do with religion. He delights in man’s mastery over nature, and music is to him his mastery over sounds. And he wonders at his own genius. Western music expresses that attitude and the harmonic system, as developed in the West, is quite suited to that purpose.

The question is: Will the Indians of the future have the same outlook as the Westerners of today? I cannot think so. Therefore the Western system will ever remain unsuited to express the Indian genius. All the efforts made to impose on India a musical system that is inadequate to bring out the finer emotions and deeper inclinations of the people cannot lead to any great achievements in the field of music.

Each country must develop its own genius, or it ceases to exist as a country. It is only when a nation’s culture is flourishing and powerful that it can borrow from other lands and assimilate what it gets. To borrow in time of poverty puts you in the clutches of the money-lender from whom you will not emerge unscathed. Indian music is at the present moment going through a difficult period and it is only by uniting efforts to restore its classical greatness that it may be preserved for future developments.