Alfred Dunshirn

REFLECTIONS ON DIONYSIAN AND ORPHIC TRADITIONS IN SOURCES POSTERIOR TO ALAIN DANIÉLOU’S SHIVA AND DIONYSOS

In this article, Alfred Dunshirn deals with the Derveni papyrus, one of the most recent archaeological findings concerning religious sources of the Mediterranean region. The papyrus contains the interpretation of a theogony and gold tablets addressing persons on their way to the afterlife. Such sources, partly related to Near Eastern creation myths, confirm some observations that Alain Daniélou puts forward in Shiva and Dionysus as well as the importance of the Dionysian element in religious practices.

Introduction

When did Dionysus die and who killed him? In this paper I should like to address the suppression or dismemberment of the Dionysian, as it appears from sources that scholars have intensively discussed since Alain Daniélou’s death. This can be of interest for thinking further about his book Shiva and Dionysus1. There Daniélou talks about the fact that the Dionysian was suppressed by religions of urban cultures, even though a place had to be “left” for Shiva-Dionysus2. In Greek myth, there are several stories about Dionysus (nearly) dying, be it his dismemberment as Zagreus or the unborn Dionysus almost perishing when Zeus appears to his mother Semele in the form of the lightning bolt3. In the intellectual realm, according to Friedrich Nietzsche’s well-known remarks,4 the dramatist Euripides, in conjunction with the questioner Socrates, put an end to the lively tradition of an important Dionysian event in Athens, namely tragedy. However, this is not the subject of the present paper, which is concerned with a testimony of an intellectual current that takes us to the time between the fifth and fourth century BCE. By ‘testimony ‘, I mean the Papyrus of Derveni, and by ‘current’, I mean Orphism.

We may consider Orphism or the Orphic religion a phenomenon within the religion of Dionysus, namely as a “male and speculative tendency” in this religious movement, which was primarily a female one5. Essential figures of the Dionysus cults are the women who figure both as protectors and wet nurses of the boy Dionysus and as rippers of the living, the wild animals. A great expert of the Dionysus religion, Karl Kerényi, shows how rationalising authors of mythological texts such as Onomacritus attributed the primordial guilt of killing Dionysus to the male persons of the myth.6 Those originally said to have rent Dionysus apart were the Curetes, the “boys” (Greek koúroi – who killed the koúros, the “boy” par excellence, i.e. Dionysus/Zeus7). They were in turn killed and burnt by Zeus’ lightning. From the soot of the vapor of the burnt Titans sprang humans8. It is believed that this story established a tendency in mystical ceremonies to address or represent the purification and deification of the individual9. So we can say that the Orphism with which we are concerned here is a phenomenon of isolation and at the same time a prospect of transcendence. On the other hand, we encounter the phenomenon of universalisation and rationalisation in the testimonies considered here.

The Derveni papyrus

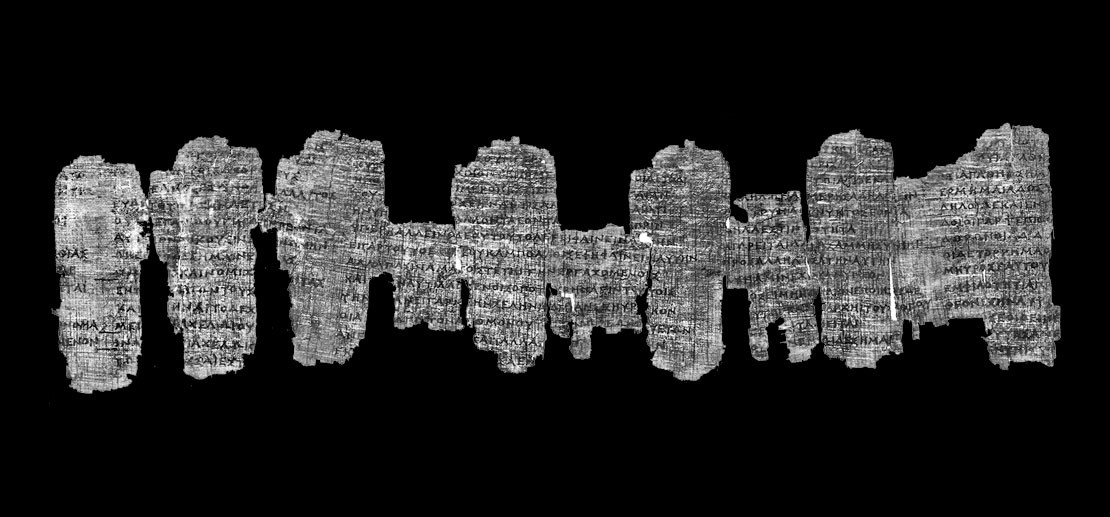

The Derveni papyrus, which is considered Europe’s oldest surviving manuscript, bears witness to this. This papyrus was found in 1962 during road construction work near a grave in a pass named Derveni, close to Thessaloniki, in Greece. The official publication of the text it contains was delayed, however, until 2006. Nevertheless, a “pirate edition” of the text was published earlier, in 198210, and scholars circulated private copies, which led to an intensive discussion in classical studies11. This text points not only to what lies beneath the earth, but to the underworld in the proper sense, as we encounter it in a funerary context.

The papyrus was to be burnt at a cremation and probably given to the cremated person on his way to the afterlife. But the writing did not burn completely, and some parts of the text (to which perhaps too much attention is paid in philology) were preserved. The papyrus fragments offer an interesting testimony of interpretations of Orphic poems in their popular form around 400 BC. Indeed, researchers assume that the text on the papyrus dates from this period. It provides the interpretation of an ‘Orphic’ theogony that may have been written around 500 BC12. In any case, the text provides us with information about ‘Orphic’ poetry, as problematic as the attribution is13, from the classical period.

The Derveni Papyrus, Thessaloniki, Archaeological Museum. Source: amth.gr

The Derveni Papyrus, Thessaloniki, Archaeological Museum. Source: amth.grUntil the discovery of the papyrus, there was much speculation about the age of the religious and mystical beliefs labelled as ‘Orphic’, which had previously been mainly known through Neoplatonism and its preoccupation with the Hieroi logoi (“Sacred Tales”), the Rhapsodic Theogony.14 Among other things, the Derveni author emphasizes that people do not inquire enough about the meaning of texts or of oracles (column 45, paragraph 14 Janko15); these people need his help to arrive at the true meaning of what is implied or hidden in myths.

Roughly speaking, this interpretative text traces all divine and cosmic events back to the noús, “reason” or “spirit”. Above all, the Derveni author interprets tales of Zeus as allegories that make the actual meaning of the Orphic theogony accessible. In allegories of this kind, gods such as Demeter and Dionysus are stripped of their divine form and explained e. g. as liver and spleen, as was done by Metrodorus of Lampsacus.16 Dionysus generally plays an important role in the Orphic theogonies: He is the son Zeus begets on Persephone, the goddess of the underworld, and the designated successor of Zeus; the young Dionysus is however dismembered.

Our author subjects all this to an allegorical interpretation in the direction of reason or the spirit (Martin West rather harshly: “The consequence is that his interpretations are uniformly false”17). Reason controls everything and brings everything forth; we can thus say that the force of life, which for the Greeks and their myths is inherent in the divine and in Dionysus, is sublimated and universalised into a force of reason. Incidentally, Euthyphron, among others, is brought into play as author of the papyrus text.18 Who is Euthyphron? We know him from Plato’s dialogue of the same name, in which he appears as an expert in matters of the divine, but who has a tough time with Socrates’ questions. This Euthyphron appears as the adequate author of the text in question – it is not a philosophical dialogue or treatise, but it advertises itself and its author. The allegorical interpretation of the Orphic poem and its author could help one to fathom the myth and grasp its truth.

Birth of Dionysus, Apulian Red Figure Volute Krater (ca. 400 BC), Taranto, National Archaeological Museum. Source: archeotaranto.altervista.org

Birth of Dionysus, Apulian Red Figure Volute Krater (ca. 400 BC), Taranto, National Archaeological Museum. Source: archeotaranto.altervista.orgIn parenthesis, it should be mentioned that the Dionysian was not, as Nietzsche’s remarks might suggest, completely suppressed in Athens around 400 BC, which the Apollonian religion of moderation would have overridden.19 Even at this time (when philosophy was at its best in Athens), a large part of the Athenian festive calendar was dominated by festivals in honour of Dionysus. I mention only the three days of the Anthesteria, the “Flower Festival”20. On the first day of the festival,21 the Pithoigia, the “opening of the wine jars”, Dionysus was freed, as it were, from his confinement, having been sewn into the wineskins or into the thigh of his father, Zeus.

On the day of the Choes, the focus was on the wife of the archon Basileus, the highest priestess of Dionysus. She was married to Dionysus and the unspeakable mysteries were incumbent upon her. The Chytroi on the third day were a commemoration of the dead. The phálloi were also materially present at this festival during processions, another topic which Daniélou treats in-depth.22

There was obviously a tendency towards an individualisation of these festivals, mysteries, and processes in the direction of a rationalising religion of redemption for the individual. Significant for this is a statement from the beginning of the preserved part of the Derveni papyrus. There, after quoting on column 39 the first verse of Parmenides’ great poem on nature, the author states on column 41, paragraph 6 Janko23 that the individual things in the cosmos are “signs” for human beings. This indicates, I think, that the world and its contents are de-potentiated – they are no longer expressions of life or divine power, they are signs, semeía – they point to something “behind”.

The Dionysian was not, as Nietzsche’s remarks might suggest, completely suppressed in Athens around 400 BC, which the Apollonian religion of moderation would have overridden.

Then we hear in the papyrus of daímones, of divine powers (col. 43, § 9 Janko). The interpreting text obviously does not regard them as supernatural mediators between humans and gods, as it is the case with the daímon Eros in Plato’s Symposium (202d–e), but they are considered – at least according to the explanations of mágoi, of experts in the rites24 – as “great oaths”, col. 43, § 9 Janko:

οἱ] δὲ [δ]αίμονεϲ, οἳ κατὰ [τοὺϲ μ]ά̣γουϲ τιμὰϲ [ἀ]έ̣ξ̣ο̣υϲι [τῶν]θεῶν ὑπηρέται δ[ίκηϲ, πα]ρ̣᾿ ἑκάϲτο`ι΄ϲ ὅρ̣[κοι]μεγ̣ά̣[λο]ι εἰϲίν, ὅπωϲπερ ἀ[λοίτηϲ θ]ε̣όϲ, τοῖ̣ϲ τὸ [φοβ]ερὸν̣ [ἀρωμ]ένοι[ϲ]·

[But the]daímones, who, according to [the] mágoi, increase the honours of [the]gods as servants of justice, are great oaths, like a [god of vengeance,]to all those who [pray for the fearful].

This conception of daímones thus already points in the direction of the later common meaning of demons as avenging underworld creatures.25 As such, demons are known to be the subject of psychoanalytical reflections on the taboo, as we can read in Freud.26 According to the papyrus, this applies at least to those who “pray for”, imprecate the terrible. The daímones are cited in the following paragraph as the cause of wine-less sacrifices being offered (col. 43, § 10 Janko), i.e. sacrifices that renounce the gift of Dionysus per se, as was customary for sacrifices to subterranean deities.

The author of this text presents himself as one who intercedes in the interest of those who do not inquire into the deeper meaning of oracles. He is the one inquiring, regarding what is prophesied, whether the “great and terrible”, the horror of Hades, is “willed by gods and right” (thémit’, col. 45, § 14 Janko). Then we read again of the souls of the departed, who can be obstructive demons. To these demons the mágoi, the rite experts, offer sacrifices. The mýstai, the initiates, bring such sacrifices, too – we thus enter the realm of the Mysteries, which have to do with preparations for the hereafter (col. 46, § 18 Janko: μύσται Εὐμενίσι προθύουσι …, “initiates sacrifice to the Eumenids …”).

In the extant text follow remarks on the assumption of rule by Zeus (col. 48, § 24 ff. Janko), who will prove to be noús, divine “Reason” who directs everything. This sovereignty of Zeus is demonstrated, among other things, by the fact that he, Zeus, has recognised the problem of the superiority of fire (col 49, § 27 Janko). Zeus took away a portion of fire so that something could form in the cosmos. In all this, the daímon is involved, whom Zeus “accepts” or “devours” (if we follow West’s textual transposition27).

Of significant importance for this cosmogony – at least in the interpretation of our author – is also Helios, the sun god.28 Zeus “swallows” this god, the “venerable” one, aidoíon (col. 53, § 39–40 Janko; as a neuter aidoíon also denotes the male sexual organ). In this context, the Derveni author mentions the stations of the sequence of the gods. Kronos succeeds Uranos – here we see one of many linguistic considerations of the Derveni author at work. He often equates words (e. g. “speak” means the same as “teach”, col. 50, § 30 Janko). Here the Derveni author ventures an etymology of the name Kronos: he as noús (reason) is the one who “pushes things”, cf. kroúesthai; we are again confronted with the orientation of everything towards the divine noús, which ultimately does not leave room for the Dionysian (col. 54, § 43 Janko):

“Οὐρανὸν͙ Εὐφρονίδην͙, ὃϲ πρώτιϲτοϲ βαϲίλευϲεν”.

“κρούοντα” τὸν “Νοῦν” πρὸϲ ἄλληλ[α]“Κ̣ρόνον” ὀνομάϲαϲ, “μέγα ῥέξαι” φηϲὶ τὸν “Οὐρανόν”

ἀφα̣ιρε̣θῆναι γὰρ τὴν βαϲιλείαν αὐτόν. “Κρόνον̣” δὲ ὠν̣ό̣μαϲεν ἀπὸ τοῦ ἔ̣[ρ]γ̣ου αὐτόν, καὶ τἄλλα κατὰ τ[ὸ]ν α̣ὐ̣[τὸν λ]ό̣γον.

“Uranos, son of the night, who became king as the very first.”

Because the “Nous” “pushes (things) against each other” (kroúonta), he called him “Kronos” (Kro-Nous) and he says that he “did great things to Uranos”. For he (Uranos) had been deprived of his dominion. He called him “Kronos” after his deed and everything else after the same principle.

This all-involving and all-emerging noús is the “counsellor Zeus”, metiéta Zeús (col. 55, § 46 Janko). The “venerable king” is also called protógonos, “firstborn”, a title that is also understood as a proper name. By means of this “firstborn”, we can connect the Derveni theogony in a broad arc with eastern cosmogonies such as the Prajāpati story or the Egyptian Re-myth.29 Protogonos, the firstborn, is conceived as the “only one” (§ 50): everything depends on him, all the gods and goddesses, the rivers and springs, everything altogether. We are witnessing the development of a religion of reason with a claim to universality and uniqueness for reason.

Zeus, as this divine reason is called by name, is further called “breath” (pnoié, pneúma) and moíra, “fate” or “destiny”, of everything (col. 57, § 57 Janko). Regarding this conception of fate “spinning” man’s destiny (col. 58, § 58 Janko), widespread among men, the Derveni author claims to put forward the correct interpretation of Orphic thought. By moíra Orpheus had meant phrónesis, “prudence” or “practical thinking” (col. 58, § 59 Janko). Zeus not only swallows Metis, but he is also identified in this text with various other of the known divine instances, namely with the Celestial Aphrodite, with Peitho, personified persuasion, as well as with Harmonia (col. 61, § 72 Janko).

In Zeus the most diverse deities coincide; we experience a unifying movement. The Derveni author underlines the originality and power of noús, alias Zeus, by having Zeus “conceive” Gaia and Uranos, “Earth” and “Sky” (col. 61, § 75 Janko). The goddess Ge, the Earth, is in turn likened to Demeter, Rhea (Zeus’ mother) and Hera (Zeus’ sister and wife). This brings us to the potential mothers of Dionysus, namely Demeter and Rhea, who conceived Dionysus incestuously with Zeus. The Derveni author also addresses Zeus’ desire to be united with “his mother” (col. 65, § 93 Janko). He interprets the expression “mother” as noús and the pronoun “his” as “good” – the divine Reason wants to connect with itself. One may be reminded of speculative philosophy of mind.

This brings us to the end of the extant text on the Derveni Papyrus. It should be clear that it is an allegorical interpretation of an ‘Orphic’ text that emphasises reason and destroys the dialectic of life and death, a dialectic that characterises the cult of Dionysus and for which – to quote the subtitle of Kerényi’s above-mentioned book – it expresses “indestructible life”.

‘Orphic’ gold tablets

Now let us turn to the positive side of a Dionysian concept in connection with the otherworldly, also attested by artefacts found under the earth. I am referring to the gold tablets found in the Greek world that provide us with information on individual religious beliefs.30 Recent discoveries about these golden leaves have enriched our knowledge on this topic.

Gold tablet from Hipponium (ca. 400 BC), Vibo Valentia, National Archaeological Museum. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Gold tablet from Hipponium (ca. 400 BC), Vibo Valentia, National Archaeological Museum. Source: Wikimedia CommonsA classic collection of the Orphicorum fragmenta was edited by Otto Kern.31 We owe the current, extensively annotated edition to Alberto Bernabé, who as the second fascicle of his Poetae Epici Graeci. Testimonia et fragmenta published the Orphicorum et Orphicis similium testimonia et fragmenta.32 This edition includes the texts of gold tablets found in the tomb of a woman at Pelinna, in Thessaly, Greece, dating to the fourth century BC.33 The corpse wore the tablet on its chest. The marble burial chamber also contained an image of a maenad, the classical companion of Bacchus.34

Such plates were found in various places in the 1970s and 1980s. They were – like the theogony of the Derveni Papyrus – assigned to an Orphic religion35 and gave rise to extensive scholarly discussion.36

With Giovanni Pugliese Carratelli, however, one can distinguish a “mnemosynic-pythagoric” group, comparable with the Buddha’s teachings,37 from a second group that speaks of painful experiences or atonements leading to a new state of mind.38 It is this second group that we will deal with here. Significant finds were made, for example, in the ancient Hipponium (Vibo Valentina in Calabria), edited by Pugliese Carratelli.39 The plates can be seen as talismans for the deceased on their way to the underworld, reminding them of what they heard in their initiations into the Mysteries.

The text of one of the two gold tablets found in Thessaly reads as follows (fragment 486 E Bernabé):40

νῦν ἔθανες καὶ νῦν ἐγένου, τρισόλβιε, ἄματι τῶιδε.

εἰπ[ε]ῖν Φερσεφό‹ναι σ᾿ ὅτι Β‹άκ›χιος·αὐτὸς·ἔλυσε·

ταῦρος·εἰς γάλ‹α› ἔθορ‹ε›ς·

αἶψα·εἰς γάλ‹α› ἔθορ‹ε›ς·

‹κ›ριὸς·ἐς γάλα ἔπεσ‹ες›.

οἶνον ἔχεις εὐδ‹αί›μον‹α› τιμήν

καὶ σὺ μὲν εἶς ὑπὸ γῆν τελέσας ἅπερ ὄλβιοι ἄλλοι.41

Now you have died and now you have come into being, thrice

blessed, on this day.

Tell Persephona that Bakchios himself freed you.

As a bull you plunged into the milk:

Suddenly you fell into the milk:

As a little goat you fell into the milk.

Wine you have to blissful honour,

And you are going underground, initiated like other blessed ones.

We encounter central elements of the Dionysian in connection with a belief in the afterlife. In the first line, the dialectic of passing and becoming is addressed, presumably by a priest speaking to the deceased. We read something similar in well-known tablets about a páthos, a “suffering” or “experience”, experienced for the first time and that leads to new dimensions.42 There, too, it is said that a little goat, this time called ériphos, fell into the milk. In this we may see the suffering of Bakchos, of Dionysus himself. The expression ériphos alludes to the story that Dionysus was “sewn in” (cf. Greek ereípho “sew”), namely into the thigh of his father, Zeus, who bore him.43 Similarly, the juice of the grapes that becomes wine is sewn into wine skins from which it is then extracted.

As the god of wine, Dionysus bears the epithet “solver”, which is also shown on the tablet: he is addressed with the epithet “Bakchios”, who has “solved” or “redeemed”, freed the deceased. This is what the bearer of the plate is supposed to say to Persephone, the goddess of the underworld. The verses are followed by formulas that were typical closings of the Mysteries.44 However, before wine is explicitly mentioned, we hear three times about the milk into which someone fell or tumbled. The fall into the milk refers, as it seems, to the fate of the dismembered Dionysus Zagreus, which was remembered for example on Crete. According to one version of the myth, the Titans cut up this Cretan Dionysus.45 Zeus burnt them to ashes with his lightning, as mentioned above. From the soot of the vapor resulting from the burnt Titans, in turn, mankind was born.46 The dismemberment and cooking of the infant Dionysus in a cauldron were reproduced in the Mysteries by the cutting up of young animals (or the myth reflects shamanic rites in the Mysteries47); the cooking of a goat recalls the reassembly of the dismembered Dionysus, just as Osiris was reassembled by Isis. And this cooking took place, as the gold tablets suggest, in milk, the medium of rebirth. This is also documented in the Phoenician area, and the biblical prohibition against seething a kid in its mother’s milk probably reflects such processes.48

In any case, addressing the milk and falling into it expresses that the mýstes, the initiate, may expect a resurrection, in the sense of leaving the human realm.

As the god of wine, Dionysus bears the epithet “solver”, which is also shown on the tablet: he is addressed with the epithet “Bakchios”, who has “solved” or “redeemed”, freed the deceased.

The Derveni Papyrus, Thessaloniki, Archaeological Museum. Source: amth.gr

The Derveni Papyrus, Thessaloniki, Archaeological Museum. Source: amth.grTablets from Thurii

Such statements about falling into the milk are not limited to the new finds in Thessaly from the 20th century. Already in the 19th century, texts of tablets from Thurii were published, among them the above-mentioned text about the páthema, the “experience”, 487 F Bernabé, 32f. Kern:

χαῖρε παθὼν τὸ πάθημα

τὸ δ᾿ οὔπω πρόσθ᾿ ἐπεπόνθεις·

θεὸς ἐγένου ἐξ ἀνθρώπου·

ἔριφος ἐς γάλα ἔπετες.

Welcome you, who’ve experienced the experience

that you’ve not experienced before:

You became God from a human being:

As a little goat you fell into the milk.

Here the apotheosis is explicitly mentioned. A hitherto “unsuffered suffering”, a special experience, namely death, leads to being God. Again, we read that the person addressed has fallen into milk. This time he is called ériphos, with the suggestive word for “little goat”, which evocates the “sewing in” of Dionysus/the wine.

Tablets from Thurii

What do we see in the recent finds from under the earth which point to the underworld? They testify to a confrontation with the Orphic, in turn pointing to the Dionysian. The allegorical interpretation, however, shows a spiritualisation. All mythical contents are interpreted in such a way that they refer to the noús, “reason” or “spirit”. We can therefore speak of a rationalisation that destroys the tension between life and death as lived out in the cults of Dionysus.

The gold tablets we have been looking at, on the other hand, testify to an individualisation. Although the initiate has to do with Dionysus, he or she does not experience an integration into the general vitality (zoé), but expects to reach a new horizon, a departure from the previous life (bíos)49, through an “unexperienced” experience.

Gold tablet from Thurii, tomb of Timpone Grande (4th century BC), Naples, National Archaeological Museum. Source: miti3000.it

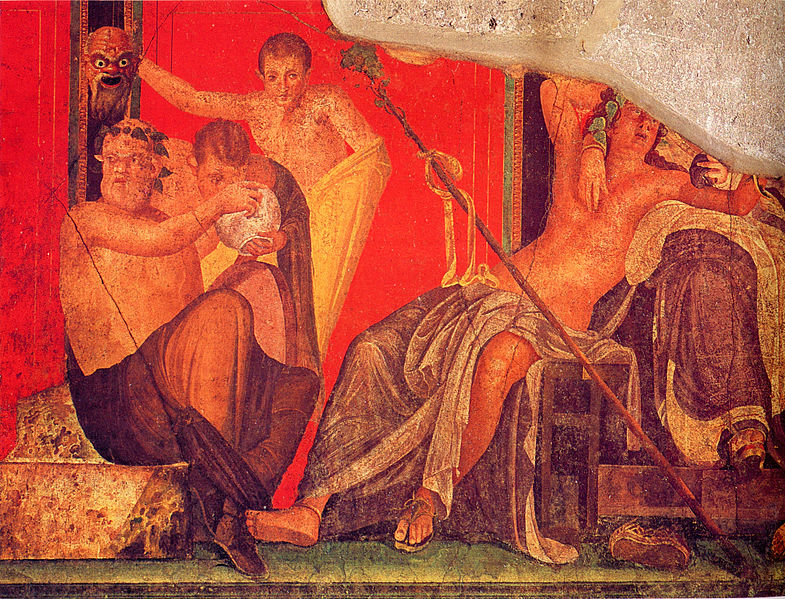

Gold tablet from Thurii, tomb of Timpone Grande (4th century BC), Naples, National Archaeological Museum. Source: miti3000.itBut who knows what information the earth still holds about Dionysus and Orphism that will change our views? – The tradition of the Dionysian cults in antiquity is long attested. Suffice it to think of the Villa dei misteri at Pompei, whose wonderful frescoes bear witness to the cult of Dionysus up to the first century CE50.

Most recently, archaeologists have discovered a stone slab from the second century with the record of a Dionysus cult association in Carinthia, Austria,51 which shows the active participation in Dionysian activities (whatever they were) at Virunum during the Roman occupation of that region.

In any case, the new finds considered here clearly confirm some of Daniélou’s observations. The Derveni papyrus, however, does not testify to a suppression of the Dionysian, but to a reinterpretation in the direction of emphasising the “superiority of reason”52. The gold tablets, on the other hand, which led us into the world of the Mysteries, confirm with their references to Dionysus Daniélou’s statement that all mystery cults are Shivaistic or Dionysian in character. 53

- First published in French under the title Shiva et Dionysos. La religion de la nature et de l’eros; de la préhistoire à l’avenir, Paris 1979.

- Alain Daniélou: Shiva und Dionysos. Die Religion der Natur und des Eros. Aus dem Französischen übersetzt von Rolf Kühn, überarbeitet von Sarah Eichner und hrsg. von Adrián Navigante, Dresden 2020, p. 61 (cf. id.: Gods of Love and Ecstasy. The Traditions of Shiva and Dionysus, Rochester 1992, p. 15).

- For an overview of the various myths associated with Dionysus and their reception in art and literature cf. Christine Harrauer and Herbert Hunger: Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie. 9., vollständig neu bearbeitete Aufl., Purkersdorf 2006, 141–148.

- Cf. e.g. Friedrich Nietzsche: Die Geburt der Tragödie. Kritische Studienausgabe. Bd. 1. Hrsg. von Giorgio Colli und Mazzino Montinari, Neuausgabe, München 1999, p. 83.

- A “männliche und spekulative Tendenz,” Karl Kerényi: Dionysos. Urbild des unzerstörbaren Lebens, Stuttgart 1994, p. 164.

- Kerényi, Dionysos, pp. 150–155.

- Cf. Daniélou’s reference to the cult of Murugan/Kumara, in: Daniélou, Shiva und Dionysos ed. Navigante, p. 75 (cf. Daniélou, Gods of Love and Ecstasy, p. 26).

- Olympiodorus, In Platonis Phaedonem commentarii 1, 3 (Orph. fragm. 220 Kern); cf. Kerényi, Dionysos, pp. 152.

- In the studies on the gold tablets, in particular Domenico Comparetti emphasized the importance of the Titan story (Domenico Comparetti: Lamine orfiche, Firenze 1910).

- [Anonymus]: “Der orphische Papyrus von Derveni”, in: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 1982, 47, pp. 1–12.

- The most substantial study published so far is by Gábor Betegh: The Derveni Papyrus. Cosmology, Theology and Interpretation, Cambridge 2004.

- Cf. Martin L. West: The Orphic Poems, Oxford 1983, pp. 108–110: the theogony on which the Derveni papyrus is based was “composed for what may fairly be called a Bacchic society” (p. 110).

- On the problematic label ‘Orphic’, cf. West, The Orphic Poems, 1–38.

- Cf. West, The Orphic Poems, p. 69.

- Numbers following Der Papyrus von Derveni. Griechisch-deutsch. Eingeleitet, übersetzt und kommentiert von Mirjam E. Kotwick basierend auf einem griechischen Text von Richard Janko, Berlin/Boston 2017.

- Cf. Der Papyrus von Derveni, ed. Kotwick p. 21.

- West, The Orphic Poems, p. 79.

- Charles H. Kahn: “Was Euthyphro the Author of the Derveni Papyrus?”, in: Laks, André and Glenn W. Most (eds.): Studies on the Derveni Papyrus, Oxford 1997, pp. 55–63. For an overview of further considerations on the authorship of the Derveni Papyrus cf. Der Papyrus von Derveni, ed. Kotwick pp. 19–23.

- Cf. note 4.

- Kerényi, Dionysos, pp. 186–193.

- For a concise overview of the three days of the festival cf. Christoph Auffahrt: “Anthesteria”, in: Cancik, Hubert and Helmuth Schneider (eds.): Der neue Pauly. Bd. 1, Stuttgart and Weimar 1996, pp. 732 f.

- Alain Daniélou: The Phallus. Sacred Symbol of Male Creative Power, Rochester 1995.

- [καὶ γὰρ ἔϲτ]ι̣ν ἕκαϲτα ϲημεῖα̣ ἀνθρώ[ποιϲ ……., text following Der Papyrus von Derveni, ed. Kotwick.

- Cf. Der Papyrus von Derveni, ed. Kotwick, p. 142.

- The major stages of this development are outlined by David L. Bradnick: Evil, Spirits and Possession. An Emergentist Theology of the demonic, Leiden and Boston 2017, pp. 20–29.

- Sigmund Freud: “Totem und Tabu. II: Das Tabu und die Ambivalenz der Gefühlsregungen”, in: id.: Studienausgabe. Band IX: Fragen der Gesellschaft. Ursprünge der Religion. Hrsg. von Alexander Mitscherlich, Angela Richards and James Strachey, Frankfurt/Main 1982, pp. 311–363, especially pp. 349–356.

- West, The Orphic Poems, p. 85.

- For the identification of the sun with Zeus and Dionysus in Hellenistic times cf. West, The Orphic TRANSCULTURAL DIALOGUES Poems, p. 206.

- Cf. West, The Orphic Poems, pp. 103–105.

- Cf. Alberto Bernabé and Ana Isabel Jiménez San Christóbal: Instructions for the Netherworld. The Orphic Gold Tablets, Leiden and Boston 2008.

- Berlin 1922.

- München and Leipzig 2005.

- For a contextualization of these tablets in the Thessalian stories about the underworld and the positive emotions towards the afterlife cf. Sofia Kravaritou and Maria Stamatopoulou: “From Alkestis to Archidike. Thessalian Attitudes to Death and the Afterlife”, in: Ekroth, Gunnel and Ingela Nilsson (eds.): Round Trip to Hades in the Eastern Mediterranean Tradition, Leiden 2018, pp.124–162; on the tomb itself pp. 149 f.

- Cf. the literary survey in Bernabé, Orphicorum et Orphicis similium testimonia et fragmenta, pp. 43–51.

- Bernabé, Orphicorum et Orphicis similium testimonia et fragmenta, p. 11.

- For a succinct history of this discussion cf. Radcliffe G. Edmonds III: “Who Are You? A Brief History of the Scholarship”, in: id. (ed.): The “Orphic” Gold Tablets and Greek Religion. Further along the Path, Cambridge 2011, 3–14.

- Cf. Giovanni Pugliese Carratelli: Le lamine d’oro orfiche. Istruzioni per il viaggio oltremondano degli iniziati greci, Milano 2001, p. 55.

- Cf. Pugliese Carratelli, Le lamine d’oro orfiche, pp. 18–19.

- Giuseppe Foti and Giovanni Pugliese Carratelli: “Un sepolcro di Hipponion e un nuovo testo orfico”, in: La parola del passato, 1974, 29, pp. 91–126.

- Cf. text and translation in Pugliese Carratelli, Le lamine d’oro orfiche, pp. 114–115; Radcliffe G. Edmonds III: “The ‘Orphic’ Gold Tablets. Texts and Translations, with Critical Apparatus and Tables”, in: id., The “Orphic” Gold Tablets, pp. 15–50, here p. 36 (fragment 485 Bernabé).

- Alternative text: κἀπ‹ι›μένει σ᾿ ὑπὸ γῆν τέλεα ἅσσαπερ ὄλβιοι ἄλλοι ‹τελέονται› – “and there await you beneath the earth the rites into which other blessed ones are initiated”.

- Orph. fragm. 32 Kern, cited by Kerényi, Dionysos, p. 158.

- Cf. note 6.

- Bernabé, Orphicorum et Orphicis similium testimonia et fragmenta, pp. 46–47.

- Most recently, Giulia Rossetto published a significant find in a palimpsest manuscript: several dozen hexameters, possibly belonging to the Orphic Rhapsodies, tell of the toys with which the Titans seduced the boy Dionysus, cf. Giulia Rossetto: “Fragments from the Orphic Rhapsodies? Hitherto Unknown Hexameters in the Palimpsest Sin. ar. NF 66”, in: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 2021, 219, pp. 34–60.

- Cf. Kerényi, Dionysos, pp. 152–158; Pugliese Carratelli, Le lamine d’oro orfiche, pp. 20–21.

- Cf. West, The Orphic Poems, pp. 147–148.

- Cf. Kerényi, Dionysos, pp. 159–160. For other interpretations of falling into milk, see Bernabé, Orphicorum et Orphicis similium testimonia et fragmenta, pp. 47–49.

- On the distinction between zoé and bíos cf. Kerényi, Dionysos, pp. 11–15.

- For a new examination of the pictorial representations of the mysteries cf. Nicole Belayche and Francesco Massa (eds.): Mystery Cults in Visual Representation in Graeco-Roman Antiquity, Leiden and Boston 2020; for the complex visual representation of Dionysus/Liber Pater in Rome cf. Stéphanie Wyler: “Images of Dionysus in Rome. The Archaic and Augustan Periods”, in: Mac Góráin, Fiachra: Dionysus and Rome. Religion and Literature, Berlin and Boston 2020, 85–110.

- Kronen Zeitung, 18.08.2021, https://www.krone.at/2487428.

- Cf. Daniélou, Shiva und Dionysos ed. Navigante, p. 61 (cf. Daniélou, Gods of Love and Ecstasy, p. 16).

- Cf. Daniélou, Shiva und Dionysos ed. Navigante, p. 64 (cf. Daniélou, Gods of Love and Ecstasy, p. 16).