Adrián Navigante

FROM “INDIAN-EUROPEAN” TO “TRANSCULTURAL”: RECONSIDERING ALAIN DANIÉLOU’S INTELLECTUAL LEGACY

In view of the Foundation’s recent change of name from India-Europe Foundation for New Dialogues to Alain Daniélou Foundation: Center for Transcultural Studies, Adrián Navigante reflects on the contextual significance of this broader field and shows that the name-change is not merely formal. On the contrary, it relates intrinsically to Alain Daniélou’s work and presents an enormous task. The essay analyzes, among other things, the intellectual and practical scope of the idea of “transculturality”, as well as its relevance for an interpretation of Alain Daniélou in the XXI century devoid of certain prejudices that have characterized his reception till now.

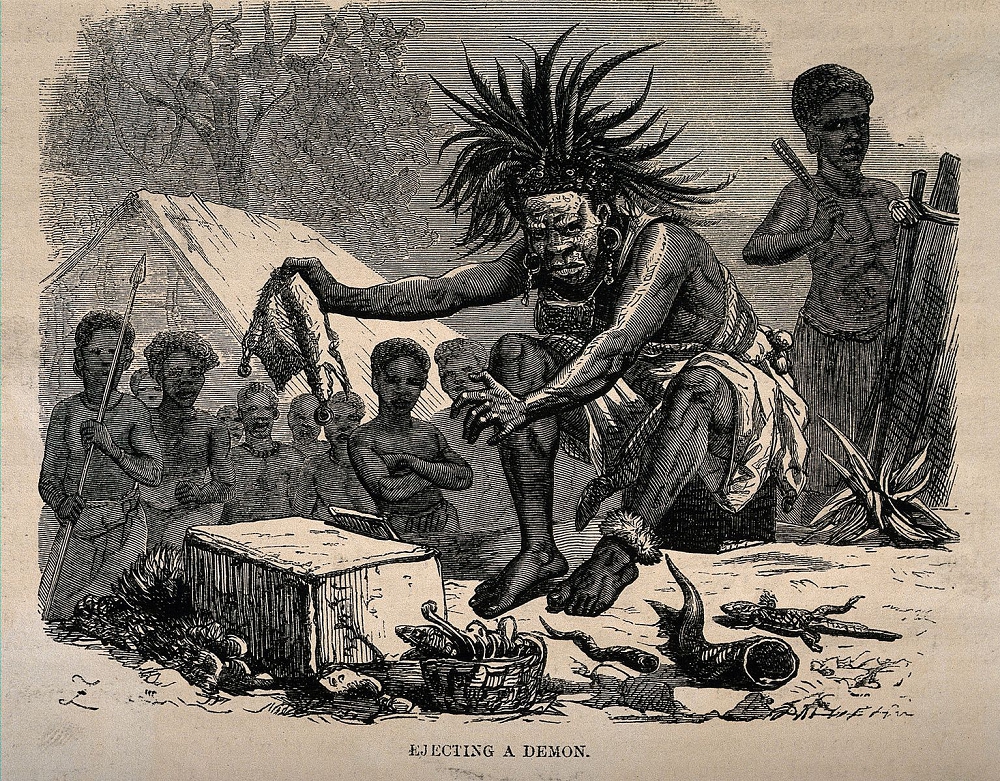

African medicine man exorcism. Wood engraving by Dalziel after J. Leech.

African medicine man exorcism. Wood engraving by Dalziel after J. Leech.What’s in a name?

It is difficult to contradict Shakespeare. Thomas Carlyle spoke of his superior intellect (equating him with a sort of divine elite); Samuel Johnson elevated him to the heights of Homer (as archetypal poet of the West); T. S. Eliot condemned critics to being inevitably wrong about him (with the hope of a ‘decent failure’ in a few cases); Harold Bloom explains to us that he invented ‘the human’ because he inaugurates the personality, he created the self as moral agent, and he colored the Western character with a universal tinge1. All these critics and authors seem to translate the very stuff by which the reader is impregnated in dealing with the English bard – the effect of his poetry and prose, his stylistic magnificence, his musicality, his genius. A specific kind of genius. His main quality is not vision, but lucidity; his writings are not peculiar or even singular, but institutional. Shakespeare’s work declares that the Spirit (that is, the Western idea) can be larger than life – and the reader (Western or Westernized) is enticed to believe it. In his best-known play, Hamlet, Shakespeare shows (by means of his style) that the richness of language surpasses our very idea(l) of it, but at the same time he deprives language (in his own workings of the plot) from any access to the substrate of Life – what we wrongly call ‘things’. The Prince of Denmark exhausts modern Western skepticism when he tells his friend Polonius that he reads merely ‘words, words, words’ (Act II, Scene II) – that is, he sees no book, no author, no world of referents, no meaningful transcendence. In Romeo and Juliet, the female heroine asks herself (rhetorically) ‘What’s in a name?’ (Act II, Scene II), anticipating modern linguistic theories about the arbitrariness of the sign. She seems to critically separate semantic content from world reality, while she laments the paradox that the reality of the world is nevertheless permeated by language to the point of artificially identifying the referent with the sign – ultimately her lover could have been re-named for the occasion and he would still be the same person (and object of desire) for her. What is the philosophical lesson behind that fit of adolescent passion? The person, beloved or not, is not in his/her name, because the world is severed from language. Humans live in a parallel sphere where meaning is permanently being evacuated, as if the resulting emptiness were the condition of our lucid participation in reality – what no other species than humankind can do.

I dare to pick up the challenge of contradicting this verdict – much as I admire Shakespeare’s work – mainly because geniuses are not independent of their contexts, and the workings of the spirit(s), as we shall see, are not (only) what the West solemnly declared. If we follow the modern trend inaugurated by the English bard in our observation of language and the world, we may say that ‘naming things’ is ultimately irrelevant, and ‘re-naming’ (those ‘already-named’ things) utterly impossible. In other words, we are never in possession of anything but the illusory solidity of ‘language-creation’: word-consistency instead of world-consistency. This may have been a lucid verdict in Shakespeare’s time, since it broke with power-illusions related to the organization of social life13 and changed the focus from institutionally accepted truths (at that time already weakened) to the individual exercise of doubt. It was the birth certificate of what is called ‘critique’ and the key to the expansion of a conquering spirit – the task of putting life at the mercy of the Western Intellect. More than four hundred years after the bard’s death, the verdict is not only questionable. It is the symptom of an outdated (and even harmful) idea of Culture. The conquering zeal of the Western spirit has shown that the power of language does not run parallel to reality: it creates and re-creates itself together with the actions led by its normative ideals.

If there is nothing in a name, we lose the whole dimension of ancestry mythology, inherited patterns of collective intricacy, non-human factors of socialization and transpersonal ties. If ‘words’ cannot reach the ‘real world’, there is an irretrievable separation of the subjective (human) agent from the network of (non-human) relations emanating from Life. The result is not the loss of Life, but a transformation of its texture according to new parameters of thought and action. These new parameters, in the case of the West, have enabled the rapid expansion of a simplified and reductive idea of reality. Science takes care of the objective dimension (which is the main territory of conquest), and literature covers the subjective need of the lost souls yearning for another (expansive, not reductive) worldview. The politics of expansion surreptitiously translates an increasing exercise of reduction. From a historical point of view, a pragmatics of concrete relations has been progressively replaced by two apparently contradictory (but in fact solidary) poles: scientific speculation on a mechanic universe (Nicolaus Copernicus) and anthropological interest in ego-centered individuals (John Locke). The modern invention of the ‘human’ is that of a subject fully severed from the texture of the world and – only as a result of that – at the same time able to conquer it. It is ‘severed’ because of a deep-rooted conviction of superiority, and its exercise of conquest translates the wish to regain the former network of relations – only to transform it into a field of governance.

Brahman priest in India. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Brahman priest in India. Source: Wikimedia Commons.Not to contradict Shakespeare on that level would mean declaring that the use of designations like ‘India-Europe’ and ‘transcultural’ to approach and deal with Alain Daniélou’s work and heritage are ultimately irrelevant. Perhaps even more: illogical and somewhat confusing. The reason seems at first sight quite convincing and appears to restitute something of a life-content within the wasteland of semantic referents: Daniélou spent so many years in India that one tends to associate him automatically and exclusively with that culture. The main question, however, is not that of associations, but that of world-configurations and their pragmatic consequences – since on that level lies the real content. How did Daniélou live and what does his work say to us today? This is a question that deserves consideration far beyond some aspects of his life that ended up becoming commonplaces (partially nurtured by some of Daniélou’s provocative declarations), such as his re-education in a traditional Hindu milieu, his initiation in Shaivism and his rejection of the modern (or universal) West in the name of ancient (and local) wisdom. One can repeat those aspects ad nauseam, but what is really contained in Daniélou’s work and what speaks to us today with a promise for the future is something else, and it demands another type of approach. In this sense, one cannot avoid contradicting Shakespeare’s verdict, which in this case means taking Alain Daniélou’s work in its whole dynamic scope.

My exercise in contradicting and challenging the Shakespearean operation of emptying language from its rapport to reality (despite the magnificent stylistic compensation of the ontological vacuum) is a way of underlining the relevance of the term ‘transcultural’ in the domain ‘Research and Intellectual Dialogue’ at the Alain Daniélou Foundation. It is a way of saying that the change of the Foundation’s name, from India-Europe Foundation for New Dialogues to Alain Daniélou Foundation: Center for Transcultural Studies, is not arbitrary. It is rather the adoption of a broader – and perhaps qualitatively different – horizon that becomes visible owing to the very substance of Daniélou’s own thought and work. From that perspective, words cannot be regarded as detached from reality, because reality is larger and more complex than what the Western project of modernity understood by it. In fact, the problem of language is not that of adequation of words to objects, but rather that of the living network of relations and world-articulation between those abstract poles. If mystical terms in Hindu cosmology are the key to gaining access to and getting hold of divine forces, if proper names in West-African traditions are a door to the ancestors and their influence on the name-carriers, if magical phrases in Amerindian tribes can reveal the spirit of non-humans forest agents (like animals or plants), it is useless to dismiss such world-configurations as ‘language mistakes’ and purify them with the reductive parameters of universality that the modern idea of ‘science’ offers to mortal beings endowed with reason. In the same way, there are traditions for which immortality is not a literary exercise in metaphor (as in modern Western literature), but a serious ritual task (as in the corpus of the Brāhmaṇas) or a matter of subtle-body architecture (as in some refined Tantric treatises). The category of ‘superstition’, when applied to such collective endeavors for the sake of their confinement in the basement of ‘primitive cultures’, might have been an effective device to perpetrate reductive knowledge standards, but it no longer suffices for the challenges of our times. It is no longer a convincing answer to the increasing interpenetration of cultures taking place in the XXI century. The answer can be convincing if it is transcultural, that is, if we pass from a vertical axis to a spiral prism, from a tree to a labyrinth, in order to properly rethink and rework terms, contents and contexts – which is precisely the contrary of what many an ‘enlightened Westerner’ fears, namely a fall into the pit of obscurantist regression.

Passage of Darkness: Towards the (real?) Other

If there is ‘something’ (and more than that) in a name and words are not simply (empty) words, it means that the modern project of the West has forgotten – or has decided to forgo – an essential step in self-reflection: coming back to itself and observing its historical movements in sufficient detail to extract hidden dimensions behind its main (economic, social and cultural) motivations. The expansionist movement of Western culture has been accompanied by an increasing curiosity in the face of the other – incarnated in and by cultural formations different from recognizable and desirable codes. In the case of the India-Europe axis, the asymmetry was symptomatic. “Traditional Hinduism”, writes Wilhelm Halbfass, “has not reached out for the West. […]It has neither recognized the foreign, the other as a possible alternative, nor as a potential source of its own identity. […]India has discovered the West and begun to respond to it in being sought out, explored, overrun and objectified by it”2. Modern Indology as the scientific exploration of India’s past was nurtured by the establishment of European power in the Indian subcontinent; in this sense, “the situation of the encounter and ‘dialogue’ between India and Europe is an uneven, asymmetrical one”3.

If self-reflection and expansion of the cultural horizon in terms of an increasing reception of the other are taken seriously, the task is to work on the arduous process of identity formation and affirmation in the West without making a fictionally homogeneous counterpart out of the (colonized) ‘other’.

Asymmetrical relations have more than one level – and identity. Although the early study of Hindu religion (mainly in its Vedic and Brahmanical expressions) consisted in measuring and modelling of religious experience according to the prototype of world religion that was Christianity4, there was a solidary counterpart to that assimilation project in the so-called Hinduization of autochthonous groups within the Indian subcontinent – all of which received the paradoxical status of ‘foreign’ or ‘outsiders’. In the conceptual pair ‘India-Europe’, the asymmetry does not only lie in the status of European colonial expansion regarding its conquered territories, but also within local groups across the subcontinent as well as its intrinsic power formations – the institutional and cultural phenomena of ‘Indianized empires’.

The reception of Brahmanism took place according to an assimilation strategy to Christianity, but it should not be overlooked that local traditions and cults of the Indian subcontinent had been in their turn Brahmanized, that is, selectively incorporated in the cultic body of a mainstream form and philosophy of ritual.

If self-reflection and expansion of the cultural horizon in terms of an increasing reception of the other are taken seriously, the task is to work on the arduous process of identity formation and affirmation in the West (from Jewish monotheism and Christian ethics to secular humanism, liberalism and the ideology of Enlightenment) without making a fictionally homogeneous counterpart out of the colonized ‘other’ – which means treating other world-configurations in their intrinsic complexity. Post-modern Western scholarship affirms that it is doing this task, and there are many steps forward being taken in that direction. The ‘non-Western other’ (whose faces are manifold) has been submitted to a critical inquiry going in both directions: that of the researched object and that of the assumptions of the researchers. This means that scholarship does not – or at least should not – believe any longer that its standpoint and tools of analysis are ‘neutral’, since neutrality is in the context of its intellectual operation a synonym of ‘pure or universal truth’ (as opposed to ‘local opinions’). In fact, they shape the very object they seek to explain5. This awareness of the impurity of the scientific object is a big step towards a better reception of the ‘non-Western other’. Still, a dimension of it (affecting the method and tools of inquiry) has not been taken seriously until very recently6, namely the paradox that even if the method is not – strictly speaking – objective, the wager of objectivity is preserved to delimit such inquiries from wild associations, arbitrary reports and shallow self-narratives about life-changing experiences in the field of the other7. Participation in the ‘other culture’ should remain external, that is, free from the long-feared passage of darkness summarized in the expression ‘going native’. Scholarship sets this limit not only for the sake of science, but (inevitably) also for the sake of domination. Transcultural reflection is mainly focused on the consequences of such ‘impurity’ and the way in which it inevitably affects the identity construction of the dominant side.

If one clings to Alain Daniélou’s anecdotal and provocative declarations (as if they were devoid of contextual factors and specific motivations), there is little to be done in the direction of transculturality. He praised the rigid Brahmanical caste organization of pre-Independence India8, whose xenology scheme (inscribed in the semantic value of the word mleccha) “identifies the foreigner, the other as violation of fundamental norms, as deficiency, deviation and lack of value”9. He rejected ethnic and cultural mixture and conceived diversity from a rather ethno-differential point of view10. He considered himself a Hindu11 and laconically declared Europe a land of exile and Western culture to be suffering from an incurable illness12. He did not avoid discussions on the role of violence in the order of creation as well as the function of blood (including human) sacrifices and tribal warfare as cohesive factors of social life. In today’s vocabulary, one would say that he was – to say the least – ‘politically incorrect’. Considering the complexity and the potential of his thought and work, I think that such a reading of Daniélou is not only objectively poor (compared to the richness of contents his work displays), but also subjectively unfair (in the light of his personal career). I shall summarize those aspects in what follows.

Missionaries with Bhil people. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Missionaries with Bhil people. Source: Wikimedia CommonsDaniélou’s engagement in dealing with the ‘non-Western other’ was remarkable for his time, and it demands serious consideration before confining it to the straitjacket of portmanteau expressions (especially when related to political opportunism). His defense of the caste-system in traditional India was a means of counterbalancing the universalist claims of the West translated into a normative and decontextualized exportation of democracy and individual rights14. Even if he didn’t overlook the intrinsic problems of the caste-system (especially due to the complexification of the social structure15), he attempted to show that its aim was not the exploitation of the lower strata by the privileged, but rather a harmonious coexistence of different groups (including migratory ones) according to a balanced distribution of social functions. His main question was not whether that system was good or bad. He aimed on the contrary at a profound understanding of it – which inevitably led him to ask what entitles non-Indians to judge such a complex institution according to prejudices emanating mainly from the projection of alien cultural standards deterring a priori any careful analysis based on experience and study. This leads us to Daniélou’s rejection of progressive cross-cultural breeding and its significance in our present context. One may wonder how he could reject a phenomenon he was himself part of16. In India he openly accepted his status of mleccha, that is, foreigner or stranger, which nonetheless did not prevent him from receiving a type of education closely related to that of Brahmins. He openly acknowledged being the product of conflicting civilizations and never attempted to reduce the highly complex reality of Hindu traditions to the emaciated image perpetrated by modern Orientalists or Western seekers of spiritual realization17. In the light of his work, it becomes clear that what he actually rejected was the radical critique of traditional structures and their strong solidarity ties, mainly because the aim of such critique was to dissolve local identity construction and preservation – as if it were the ‘source of all evil’ – in the name of ‘progress’ coming from the outside. His Tales of the Ganges articulate this aspect with a strong anticolonial bent, for example in the tale “The Cattle of the Gods”, where the rejection and progressive destruction of the local wisdom incarnated by rural priests and their tribal cults goes hand in hand with the British and modern Brahmins’ increasing domination in the traditional area of the Indian subcontinent18.

Daniélou’s defense of local traditions and certain deep-rooted canonical standards of knowledge may be one-sided (to counterbalance the dominant trends of dissolution), but it is not idealistic. It accepts and even embraces an inextricable coexistence of beauty and cruelty, light and darkness, pleasure and pain at all levels of manifested existence. If ‘pagan religion’ (for Daniélou a “religion of Nature”19) and tribal organization (as the archaic core of traditional societies) are privileged over the forms of complex societies typical of modern Western culture, it is not because they are the ultimate panacea to all problems, but rather because they are restricted frames in the exercise of human misery and much more authentic attempts to decenter the human and include the environmental milieu in the logic of fundamental interactions (on which life itself depends). His critique of urban structures and their alienation from Nature is not only applied to Western progress, but even to local standards or urbanization in ancient India, for example the passage from the pre-Vedic civilization of the Indus Valley to the classical Brahmanical system that emerged out of the so-called ‘second urbanization’. But Daniélou knew that pre-urban societies were too complex to make elementary forms of religion and collective life out of them. His effort was to delve into the ‘difference(s)’ and extract a lesson to face the challenges of present crises. The difference is not only incarnated in India with regard to Europe, but also within India (tribal and local cults vs. mainstream religious movements) and within Europe (in the difference between pagan and Christian, ancient and modern, etc.) and also elsewhere (wherever Daniélou was able to retrieve what he called ‘Shaivite-Dionysian aspects’ in non-Western socio-religious formations: African, Amerindian, and others)20.

Transculturality as a Global Challenge

Considered with the necessary attention and thoroughness, Daniélou’s artistic and intellectual production can be seen as an attempt to conceive humanity no longer as the ‘crown of creation’ (that is, a middle and perfective stratum between the lower sphere of nature – instinctual bonds devoid of spirit – and God – pure Spirit free from the limitations of nature)21, but rather as part of a complex ontological scaffolding where the distinctions between humans, spirits/gods, animals, plants, microorganisms etc. are fluid and not at all dependent on an exclusively discrete scale of existence (matter-spirit duality) and cognition (knowledge vs. faith, science vs. superstition, insight vs. imagination, etc.). The ‘animistic attitude’ to which Daniélou refers in his book Shiva and Dionysus22 is no sentimental wish in the face of an alienated (technocratic and ethnocentric) society but something much deeper and more complex: the possibility of conceiving ‘non-human subjectivities’ – which in the Western reflection on the other took shape only towards the end of the XX century in the field of ethnology23. The main difference between his conception and post-modern and/or post-colonialist attempts at Western self-critique lies in the fact that for Daniélou such transformation of consciousness is no merely theoretical exercise; it begins with a re-education of perception and a modified attention towards the ‘environment’ before it becomes a theory and a generalized worldview. He developed this aspect mainly in his Tales of the Ganges and Tales of the Labyrinth, but it was also an attitude he integrated into his own life – which became quite clear after his return to Europe in the 1960s. In this context, Daniélou refers to societies of the past (Minoan, Etruscan, Assyrian, etc.) which managed to integrate the powers of Nature within the specificity of the human adventure, pointing that the past seems closed and irretrievable mainly because we remain on the level of a consciousness focused on severing levels of existence and denying the fundamental interconnectedness of manifested reality. His Dravidian hypothesis attempting to bridge certain aspects of the Indus Valley civilization with some traditions of Sub-Saharan Africa24 as well as his comparison between Hindu yogic techniques and shamanic practices of the Amerindian tribes of South America25 are also signs of his tendency to go beyond already fixed limits of understanding (imposed by a specific cultural influence) by means of deeper questioning and renewed observation – and vision.

The prefix trans- in the term ‘trans-cultural’ intends to question the deep-rooted presuppositions of the very operation that founded the ‘universality’ and ‘superiority’ of Western thought, including the idea of the human and the image of the non-human that results from it.

I regard the afore-mentioned aspect of Daniélou’s thought as ‘transcultural’ avant la lettre, not only because it shows an openness of mind to learn from other cultures other than the Western without interfering prejudices, but also because the prefix trans- in the term ‘trans-cultural’ intends to question even the deep-rooted presuppositions of the very operation that founded the ‘universality’ and ‘superiority’ of Western thought, among others the idea of the human and the image of the non-human that results from it. In de-centering mankind from the core of creation, Daniélou allows further reflection on taken-for-granted ideas and concepts that are in no way fixed once and for all, but rather the result of a process, for example the conviction that ‘culture’ has to do exclusively with ‘human activity’ – for the Western mind the only evidence of what is called ‘subjectivity’ or ‘spirit’ – and ‘nature’ with a neutral, objective and quantifiable ‘reality’ (of matter) external and alien to the ‘(human) life of the spirit’. Daniélou challenges such convictions by means of his own experience in India and the philosophy he extracts from it (which he called ‘Shaivite-Dionysian’ to link the divine element directly with the forces of Nature). This is the main intellectual challenge to be picked up in the reception of Daniélou’s work, since ‘transculturality’ and the idea of ‘humanism’ have been hitherto defined out of two main parameters: 1. ‘Culture’ as human practice and only instance of subjectivity or spiritual activity (as opposed to ‘dead nature’). 2. Transculturality as an understanding of other cultures (than the one from which the observation is made) on the basis of the same idea of culture26 and according to a vertical scheme of values: from archaic and regressive (and lower) to modern and progressive (and higher)27. Within those parameters, transculturality in the strong sense of the term could not even be born.

Zulu medicine man. Source: Welcomecollection.org.

Zulu medicine man. Source: Welcomecollection.org.When can ‘transculturality’ be said to have been born? One could summarize the conditions of its birth by resorting to some key aspects set forth by German philosopher Wolfgang Welsch. 1. Transculturality breaks with the notion of ‘culture’ as a self-contained sphere delimiting itself from others (as paradigmatically conceived by Johann Gottfried von Herder28). 2. Transculturality distinguishes itself from interculturality and multiculturality, since the last two notions remained attached to the idea of a self-contained sphere (with a pluralized extension in the notion of interculturality and a multipole unity in the notion of multiculturality). 3. Transculturality implies an inner plurality preceding the constitution of each delimited cultural unit, as well as the fluid borders and identities of the latter in a process of permanent (self-)reshaping. 4. What characterizes the exercise of ‘reason’ in the context of transculturality is not a conceptual superordination of phenomena, but rather a transversal dispositive bridging over two or more heterogeneous instances – and being influenced by such instances in its own (open-ended) synthetic process29.

Wolfgang Welsch speaks of the self-evident character of transculturality in the history of humankind30, which means that collective human experience is essentially transcultural. This amplification of the concept seems to me questionable, since it sacrifices its historical specificity. An unprecedented interpenetration of cultures took place with the ‘European age of discovery’ (from the XV to the XIX century), which for many theoreticians coincides in a certain way with the term ‘globalization’ – even if the latter was thematized strictly speaking after the fall of the Soviet Union, that is, in the 1990s. In fact, colonial expeditions and the resulting expansion of cultural horizons resulted in the ambition of integrating the other by erasing its features of exteriority, but this considerable step in expansion also changed the internal structure of the identity pole of travelers and colonizers. One is never the same after an encounter with the other, not only because that other is (externally) different, but also because of the retroactive discovery that ‘sameness’ is a blurred perception of internal differences already existing in each identity-pole. Transculturality is in this sense strictly related to the globalization process of modern times, but only inasmuch as one considers that the very movement of that cultural expansion is not linear or one-sided. Quite the contrary: the key to deepen the notion is to not to think so much about the expansion movement but about the process that takes place when the other becomes impregnated in the identity-field of the conquering force – which is the inevitable consequence of a real ‘encounter’.

The last point is of utmost importance, since ultimately transculturality does not consist in recognizing or understanding or even manipulating the other. It is rather about reaching the subtractive gap of alterity where the whole process is turned upside down, that is, not only reconceiving but also reshaping the world from the perspective of the other – without fully neutralizing one’s own traces in that process. When Daniélou says that life in traditional India took him to the limits of his mental faculties31, or that Hindu reality escaped all divagations that could fit into the quest of an orientalist public32, or that anglicized Indians and colonial civil servants considered him “a European turned native”33, he seems to incarnate the type of transversal thought that constitutes the global challenge of transculturality in our time, since he was not somebody who merely went abroad and learned from a foreign culture. He changed his own structure of feeling and thinking, and afterwards he recaptured his own (temporarily sublated) identity in order to reshape it and renew it according to that transformation.

In view of all this, one can venture the following judgment: there are many levels of reality in a name. The passage from ‘Indian-European’ to ‘transcultural’ is an expansion of horizon from the seeds Daniélou planted along his path, which are invisible – because they have been buried by the weight of history (human projects usually resist or avoid the path of ‘wisdom’). The task is to extract those seeds and relocate them according to the needs – or rather the demands – of the new context: 1. No clear delimitation between nature and culture, but rather a socio-cosmic field of relations in which predicates like ‘subjectivity’ and ‘personhood’ can be extended to non-humans34. 2. A valid recognition of the admixture of subjects and objects in a dynamic interaction that is no longer dominated by the human (ego-)factor, but only partially channeled and filtered by it35. 3. A type of research and approach to the different levels of reality (human and non-human) that Alain Daniélou defined as “knowledge of the goose [haṃsa]”36, consisting in the ability to extract the essential values in each research process. In his own words: “If one studies a system to retrieve its truth, it is one thing. If one studies it as a bizarre curiosity […], it leads to nothing”37. By ‘system’ Daniélou understands a specific world-configuration, the ‘truth’ of which can only be grasped by giving up the superior standpoint of the observer and delving into the field of the other. At that point, a real participation begins to take place, and the process gains transcultural significance, since the participant is confronted with new contents and automatically forced to reshape those he had carried so far as utter convictions.

In the light of the former considerations, one can say that ‘transcultural studies’ in the context of the Alain Daniélou Foundation do not only have to do with a critical revision of Western narratives and their asymmetric presentation of cultural exchange processes (in terms of ‘civilization and barbarism’, ‘religion and superstition’ or ‘science and belief’)38. It means opening the horizon of reflection and exchange towards local non-European traditions in different parts of the world (following the traces of Alain Daniélou: India, Africa, America, Australia, as well as remnants of local traditions in Europe39), but not merely as ‘objects of study’. Such traditions are living world-configurations with their own concepts, modes of behavior and socialization and distribution of beings in a specific setting. What can we learn from them by stepping out of our comfort zone? What can we learn from them keeping nonetheless that part of ‘scholarly knowledge’ accumulated in the West that still today – through arduous and constructive self-critique – opens doors towards a dialogue devoid of major prejudices? Such questions are the challenge of a Center for Transcultural Studies like the one the Alain Daniélou Foundation proposes from now on.

- 1 Bloom goes as far as saying that Shakespeare is our “secular Scripture”, that is, “the fixed center of the Western canon” (Harold Bloom, Shakespeare. The Invention of the Human, New York 1998, p. 3).

- Wilhelm Halbfass, India and Europe. An Essay in Understanding, New York 1988, p. 172.

- Wilhelm Halbfass, Ibidem, p. 173.

- In this respect, cf. Timothy Fitzgerald, “Hinduism and the ‘World Religion’ Fallacy”, in: Religion 20, N°2 (1990), pp. 101-118.

- Cf. Richard King, „The Copernican Turn in the Study of Religion”, in: Method and Theory in the Study of Religion, 25, N° 2 (2013), pp. 145-153, especially p. 138.

- I mean the changes in the field of anthropology after the so-called ‘ontological turn’, which ended up questioning universal parameters of description as ethno-centric strategies of ‘othering’ and deconstructing their asymmetrical results (cf. among others Eduardo Viveiro de Castro, A Inconstância da Alma Selvagem, São Paulo, 2002; Philippe Descola, Par-delà nature et culture, Paris 2005; Marshall Sahlins, What Kingship is – and is Not, Chicago 2014).

- Such attempts abound, and most of them are an exacerbation of individual or private experiences nonchalantly declared as universally valid – something which can be seen as a main feature of the New-Age movement.

- Alain Daniélou, La civilisation des différences, Paris 2003, pp. 64-66. A much broader expression of his views can be found in Alain Daniélou Les quatre sens de la vie et la structure de l’Inde traditionnelle, Monaco 1992 [first edition Paris 1963]Chapitre 2 : Les bases de l’ordre social, pp. 24-66.

- Wilhelm Halbfass, India and Europa. An Essay in Understanding, p. 176.

- One clear example in Alain Daniélou, La civilisation des différences, pp. 73-75. Cf. also Alain Daniélou, Le chemin du labyrinthe, Lausanne 2015, p. 310.

- It suffices to consider the title of his autobiography’s last chapter: “Le monde occidental vu par un hindou [the Western world seen by a Hindu]”, in: Le chemin du labyrinthe, pp. 299-320.

- Concerning his perception of Europe after his return from India in the 1960s, Daniélou declares the following: “Europe was for me a land of exile. It could be nice and interesting, but it was not my homeland, a land I felt solidary with” (Le chemin du labyrinthe, p. 217). In the last reflections of his autobiography, he is even more severe: “Equipped with this background [in traditional Hindu knowledge], I began to reestablish a connection with Europe, and the latter appeared to me as a sick world region suffering from a kind of cancer, out of which certain cells expand themselves uncontrollably and little by little contaminate all the others” (Ibidem, p. 301).

- In this respect, see among others Alain Daniélou, Shiva et Dionysos, pp. XX.

- As Ingeborg Maus clearly shows, human rights are subjective rights, and as such they cannot be imposed by outer instances – in the objective sphere of politics – coming from beyond the social configuration of the ones who ‘receive’ them (cf. Ingeborg Maus, Menschenrechte, Demokratie und Frieden, Frankfurt 2015, pp. 11-12). This question is intrinsically related to the inherent amalgamation of the notion of freedom with the spectrum of action of the human individual purported by modern liberalism.

- “The Indian system [here: the caste system], like any other, has its faults, but it deserves to be examined in depth instead of being portrayed as an abomination by people who have never been in contact with its happy victims” (Alain Daniélou, Le chemin du labyrinthe, p. 319; cf. Alain Daniélou, La civilisation des différences, pp. 47-49).

- “Like the modern Indians I criticize so severely, I too am a product of conflicting civilizations” (Alain Daniélou, The Way to the Labyrinth, New York 1987, p. 218. This passage does not exist in the French original).

- Cf. Le chemin du labyrinthe, p. 231.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Le bétail des dieux et autres contes gangétiques, Monaco 1994 [first edition Paris 1962], especially pp. 166-168, where the history of the colonial ‘modernization’ of the village of Koshi is retold as an outrage towards the divine presences and autochthonous forces of the place.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Shiva et Dionysos, Paris 2008 [first edition 1979], p. 20.

- If Shaivism is for Daniélou a religion of Nature and transcends the Indian territory and Dionysian religion is the Western counterpart of it, this means that the conceptual pair “Shaivite-Dionysian” can be applied to other traditional cultural complexes outside the India-Europe axis. Essays like “Relation entre les cultures dravidiennes et négro-africaines” (in: Alain Daniélou, La civilisation des différences, pp. 145-165) and “Les divinités hallucinogènes” (in : Alain Daniélou, Yoga, Kâma : le corps est un temple, pp. 121-125) provide sound evidence of this point – not to speak of his endeavors for the UNESCO Collection in the field of music.

- There is an undeniable continuity between this monotheistic scheme and the secular idea of progress, since in the latter the human ratio (and therefore the workings of the spirit beyond the realm of matter) is considered the very organ of development and inner growth against the regressive power of natural instincts. This is why modern conceptions of history, even with atheist and materialist traits (like that of Marxism), can be seen as parallels to Christian eschatology, while the role of epistemic knowledge with the ‘enlightenment’ it brings to humans – on both an empirical and speculative level – remains a secular version of the ‘divine intellect’ in monotheistic religions.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Shiva et Dionysos, Paris 1979, p. 34.

- The forerunners of this epistemological and ontological turn date back to the 1960s, and the shining example is Irving Hallowell’s essay on Ojibwa ontology (Ojibwa Ontology, Behavior and World View, in: Stanley Diamond (ed.), Culture and History. Essays in Honor of Paul Radin, New York 1960, pp. 19-52), in which the latter shows that the category of ‘person’ for this North American Indian people extends beyond the human realm. Such intuitions became a remarkably articulated corpus of research work with a strong theoretical basis with authors like Philippe Descola, Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, Roy Wagner and Tim Ingold. – among others.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Relations entre les cultures dravidiennes et négro-africaines, in: La civilisation des différences, Paris 2003, pp. 151-165.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Les divinités hallucinogènes, in: Yoga, Kâma. Le corps est un temple, Paris 2005, pp. 121-125.

- The uniformity of the idea of culture is essentially linked with the notion of humanism and therefore attained by means of postulating an ‘essence of the human’ as common ground to judge the productions of meaning of any social group independently of its context. This is a guiding thread not only in the humanism of the Renaissance (Pico della Mirandola, Marsilio Ficino) and the XIX century (August Böckh, Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorf), but also in the ‘new humanism’ of the post- World-War II period (cf. Karl Jaspers, Über Bedingungen und Möglichkeiten eines neuen Humanismus, Stuttgart 1978 [first edition 1951]) and even in the ‘intercultural humanism’ of Jörg Rüsen at the beginning of the XXI century (cf. Jörg Rüsen, Humanismus interkulturell denken: Theorie und Methodenprobleme, in: Kerstin Andermann – Andreas Jürgens (ed.), Mythos, Geist, Kultur, Padeborn 2013, pp. 267-284).

- The presupposed value judgement in such a conception implies among others the conviction that the more archaic humans are, the closest they are to ‘nature’ (and farthest from ‘culture’). For a convincing scholarly refutation of that prejudice in the field of anthropology (still present in many human sciences), see Philippe Descola, Par-delà nature et culture, Paris 2005, pp. 18-19.

- Cf. Johann Gottfried von Herder, Auch eine Philosophie der Geschichte zur Bildung der Menschheit, Frankfurt 1967 [first published in 1774].

- For the first three aspects cf. Wolfgang Welsch, Transkulturalität: Realität, Geschichte, Aufgabe, Wien 2017, pp. 10-11 and 22-24. For the fourth aspect cf. Wolfgang Welsch, Unsere Postmoderne Moderne, Berlin 2008, Chapter XI: Transversale Vernunft, pp. 295-318.

- Cf. Wolfgang Welsch, Transkulturalität, p. 31.

- Alain Daniélou, Le chemin du labyrinthe, p. 139.

- Alain Daniélou, Ibidem, p. 231.

- Alain Daniélou, The Way to the Labyrinth, TRANSCULTURAL DIALOGUES 16p. 218. This passage is missing in the French original.

- Cf. Kaj Århem, Ecosofía Makuna, in: François Correa (ed.), La Selva Humanizada: Ecología Alternativa en el Trópico Húmedo Colombiano, Colombia 1990, pp. 109-126.

- Cf. Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, The Relative Native. Essays on Indigenous Conceptual Worlds, Chicago 2016, p. 241.

- Alain Daniélou, Essayer de comprendre, in: Yoga, Kâma. Le corps est un temple, p. 47.

- Alain Daniélou, Ibidem, pp. 44-45.

- A revision of such concepts can be very illuminating to historically understand Western prejudices, but it still preserves the politics of objectification that constitutes the main tool of ideological domination. In other words, the prescriptive amalgamation of the universalization process with an objective truth valid for each cultural group is the very thing that prevents such observers from really grasping the realities they intend to describe.

- This historical axis concerning Europe should not be taken in a strictly archeological sense, but rather as an anthropological initiative with focus on what is still embedded in certain practices and modes of socialization characterizing Western post-modernity from archaic, ancient or non-urban world-configurations in which an alternative to the increasing homogenization of the neoliberal world-project can take shape. The revival of paganism in its manifold references as well as new forms of ecological awareness related with a reconsideration of the expression ‘religion of Nature’ are two good examples of such differential phenomena, which are never fully European but always transversally impregnated by non-European references.