- » Interview with Alain Daniélou, PRE-ARYAN SHAIVITE CULTURE: A TRADITION TO BE RECOVERED

- » Sunandan Chowdhury, East and West in Rabindranath Tagore

- » Christof Zotter, BĀBĀ KĪNĀRĀM AND THE AGHORĪ TRADITION IN NORTHERN INDIA

- » Basile Goudabla Kligueh, Vodu and Nature: The Vodu Adept’s Communion with Nature

- » Fabrizia Baldissera, Notes on Maṇḍalas, cakras, and the resilience of the circular icon in contemporary Indian imagery

Basile Goudabla Kligueh

Social Anthropologist and Vodu priest

Translation from the french by kenneth hurry

Basile Kligueh knows African Vodu from the inside and has conducted long-term research on it; he offers a comprehensive picture of this religion based on its cosmology, reconstructing a way of life that brings us closer to Nature and its divine powers.

The real spelling of the word is VODU (in Ewe) or VODUN (in Fon). Ewe and Fon are the two main languages among the Aja-Tado, the people covering Africa’s West Coast, from the Nigeria-Benin border to the Upper Volta Region of Ghana, including Togo: they number over fifty million.

Nowadays, only the Aja-Tado can claim that the word VODU means something in their many languages. In the many Aja-Tado languages, and particularly in Ewe, Vodu means the World of the Invisible Ones. The term is a contraction of the expression “Evowo fé du”. Translated using popular etymology, it means the World of the Invisible Ones.

In the West, we are usually familiar with “Voodoo” from its variants in Haiti and Latin America. It is also related to Candomblé, Macumba or Santeria. These latter kinds of spiritualism are tainted by Christian practices, because Vodu is one of the few kinds of spirituality that adapts itself in time and space. It resorts to Nature and merges with its environment.

From the farthest Western coast of Africa, among the Aja-Tado, Vodu set off for the New World with the slave trade.

To understand Vodu, you must first understand its operating principle and insert this principle into the life of the Vodu adept: lastly, Vodu Cosmogony will demonstrate how the Vodu adept utilises his environment to draw on the Primordial Energy of Nature, which is called the Invisible. Is that a religion, or way of life?

The Principle of Vodu

Vodu goes from the psyche to the physical; the invisible is visited to throw light on the visible; all Vodu rites constitute a ritual drama that makes subtle suggestions, through the five senses, to the psyche, which in turn reacts on the physical body through somatisation.

The world in which the Vodu adept lives has both a visible and an invisible side or, in scientifically acceptable terms, a physical and a psychic side. Whatever the Vodu adept deems true in the visible, material or physical world is for him first realised in the invisible world or psyche.

This invisible world is called “Fetomé”, the origin of whatever is born on Earth. This superterrestrial world also represents the memory of Mawu, the Supreme Being. We should add that Mawu’s memory represents the collective psyche, of which the individual psyche is a link in a chain.

For the Vodu adept, the visible is only a feeble materialisation of the invisible, the invisible controls the visible. He believes that he is conditioned by the dynamics of the invisible realm. How does he deal with that?

A few examples will help to understand better this question of the visible/invisible mechanism.

Let us consider the trauma caused by an accident, whatever it may be. According to the seriousness of the accident, the victim will remember, long afterwards, all the details of the event. He remembers to the extent that he feels he is dying, both there and now. Science notes and recognises this condition, which is called “trauma”. Victims often receive psychological aid.

Whatever explanations science gives to the principle of memory, I propose the notion of “psychic eyes”. Thus, it is with psychic eyes that the victim sees again the details of his accident, by extrapolation: the individual’s five psychic senses.

In Vodu, psychic messages are sent from far away or near at hand, conceptual or full of imagery, sad or happy, constraining or appeasing. Nowadays, this principle is starting to be used for certain ailments in some Western hospitals, by means of hypnosis.

Each situation constitutes a case apart, but the Vodu adept always proceeds from the inner to the outer, from the invisible towards the visible.

Let us suppose you wish to reproduce someone’s head for the purpose of healing. This means that a disharmony takes place at the level of the person’s head, which may range from simple matters with no outcome to madness itself. In this case, an anthropomorphic head is made, representing the patient’s head. The ceremony or ritual drama witnessed by the patient formulates clear and precise messages that the five senses, as channels of communication, understand and integrate. Sometimes, the subtle nature of the message goes beyond the understanding of the five senses, but the psyche records and integrates them perfectly. In such a case, we may think of subliminal images.

The individual is confronted by his own head, which he must integrate: the mirror of himself

The individual is confronted by his own head, which he must integrate: the mirror of himselfPhoto: xxx

The ritual drama of making the anthropomorphic statuette whispers to the five senses that “his head is being made”. This is what I call suggestion. The patient goes back home with the statuette of his own head. Later, he must perform certain rites more or less regularly with the statuette; not only to continue the rebalancing rite for his own head, but also – and above all – to reintegrate it. This is what I term autosuggestion.

The individual’s psyche can be tuned with his physical side by replacing the patient with a family member or animal (ram, chicken, pigeon, etc.). This can be performed either in the patient’s presence, or during the ritual drama in his absence. The case of Nicéphore Soglo, a former president of the Republic of Benin, provides a good illustration.

“During the first democratic presidential elections in Benin, Nicéphore Soglo was very sick. He was unable to stand and his bodyguards had to support him to the ballot box. A spell had been cast on him. France repatriated Mr. Soglo to Paris and hospitalized him at the Val de Grâce. Leading French medical specialists saw their illustrious patient slipping away from them and could not diagnose his sickness. His family brought from Kétou a traditional practitioner, who worked in parallel with the invisible forces to rebalance the president while modern Western medicine revigorated his physical body”¹.

For the Vodu adept, all our ills and joys dwell first in our psyche: our physical body and its ecological environment are but the poor vessels of the material manifestations of the invisible, of the psyche.

Vodu, a way of life

Over twenty years ago, in my doctoral thesis, I maintained that Vodu is a religion. Nowadays, however, I doubt it is just a religion. The more I go into it, the more I see Vodu as a philosophy, a way of life, a spirituality in which the human being finds his balance and reconciles himself with his environment. At the same time, the environment turns out to be very complex. It starts with the Vodu adept himself, extending to his family, both on his father’s and mother’s sides. The environment embraces society and includes nature. The common point to all these environments lies in their visible and invisible, physical and psychic aspects; two opposites that support, penetrate and balance each other.

Every three years, the Malgaches dig up the family bones: the ceremony consists in exhuming the remains of an ancestor, and gathering the whole extended family to have a feast. The bones are replaced in a new shroud and reburied.

Among Vodu adepts, no exhumation takes place.

The fact of not exhuming the dead belongs to the sphere of Ancestor worship. In our prayers, we invoke them in a way that suggests that they are absent but present. They are in the invisible realm, in our memories, transmitted from generation to generation. This is a collective memory, to which our prayers all too often have recourse: not only do we invoke them systematically in our prayers, but the living must also harmonise with the spirits of the Ancestors, and there is also the question of reincarnation.

In certain Ewe communities, it is forbidden to eat bat meat, which is an excellent red meat. Dove meat is also forbidden. Observing these taboos honours the memory of the Ancestors and Nature. This is because, at a certain moment in our migratory history, these animals saved the life of our Ancestors when they pleaded for the aid of the Supreme Being, Mawu, in times of peril. Even intellectuals observe these taboos, albeit without understanding the reason for them, nor asking why, since the whole world is harmonised thereby.

Among most of the Ewé, male babies are circumcised after their eighth day, but only if their umbilical cord has fallen off. This operation, which plays a primary role in hygiene, has to be understood at a second level: when the umbilical cord falls off, the child no longer belongs only to his mother, but to the whole community. This is why, on the eighth day – only if the umbilical cord has fallen off – the child, whether boy or girl, is presented to the sun and its first name is revealed in public.

The purpose of the yam or maize festival is to give thanks to Nature, particularly the environment and the spirits of the ancestors, for giving us the harvest. Here, nature and the spirits of the ancestors are related to Mawu, the Supreme Being. Without performing these festive rituals, no one in the community concerned can eat the new yams or the latest maize harvest. For these festivals, members who have moved away return to the community, and the whole extended family is reunited at least once a year.

In actual fact, the festival of the sacred stone in the south of Togo commemorates the spirits of those Ancestors who made the one-way journey into slavery. To all appearances, an ox is offered to the sea so that the Supreme Being will provide an abundance of fish. Most of the population are not fishermen however, but merchants, and in reality the ox is offered instead of a human being, so that no child belonging to the community may ever again make this journey with no return.

The festival of the sacred stone in the south of Togo commemorates the spirits of those Ancestors who made the one-way journey into slavery

With regard to individual taboos, they can be classified in two categories: taboos linked to a Vodu that treats sickness, and taboos linked to initiation into Fa-destiny. Such taboos are prophylactic. Some special types of Vodu are for the treatment of certain kinds of sickness. This means that the ecological ingredients that compose the Vodu serve to treat sickness. If you are healed of your sickness in the temple of this particular Vodu or by a priest of this Vodu, you will often be considered as belonging to the community of this Vodu. You become one of its “Children”. It goes without saying that you observe the precepts and taboos of this Vodu, because you have a particular profile.

You can also be initiated into your destiny. I call it the Fa-destiny. It is the Word (Breath) through which the Supreme Being (Mawu) has fashioned your present incarnation. This word constitutes a profile: at a minimum it traces the outlines of the fields in which your life will be successful. The allegories of the sign of your Fa-destiny (Kpôli = the fence being erected) show what the ecological elements of “Nature” (Cosmos?), often personified (cf. Lafontaine’s Fables for example; others would say “gods”), have done to Fetomé, Mawu’s memory, before being on earth today. These allegories can make you in the field of Fetomé a rat, a monkey, a lion, a snake, a baobab, or even cotton, and so on. Each of these elements constitutes a very precise profile that the priests must conjure out of Fetomé (the Supreme Being’s Memory) and adapt their characteristics and properties to the life of the initiate. In this, we see what they do to nourish, defend and protect themselves: in short, their life. To give an example of this: the sign Fu-mèdzi means that when the tortoise withdraws into its shell, no predator can catch it. Indeed, when the tortoise withdraws into its shell, what we have is a round ball with nothing coming out of it. An initiate of this sign may be physically plump. As a character, the person must (his main taboo) always round off the corners of everything in his of her life. The strange lines that decorate the tortoise’s shell are the traces left by the talons of sparrowhawks, lions, and panthers that have sought to catch and eat the tortoise. But their talons, however sharp they may be, only slide off the tortoise’s shell. This means that the struggles of the Fu-mèdzi initiate will leave visible and durable traces on his or her life. The taboos of this initiate may be not to eat tortoises or kill them, to be always vigilant, and to reject compromise. Very often, the taboos intervene when the person does exactly the contrary of what is good for everyone else. At that point, by way of example, the following may be said to the Fu-mèdzi initiate: “Don’t forget that, although the tortoise has withdrawn into his shell, when fire is applied to his behind, he comes out!”

Sometimes, new initiates say: “Me? I’m used to eating this meat”, or “That’s my favourite colour! That’s how I see things; that’s how I’ve always lived!”

Personally, I propose a deal to the new initiate: for one week, he must do what he usually does. The following week, he must scrupulously observe the taboos. Then, he makes his choice. So far, they voluntarily choose the taboos after experiencing them in their own lives.

I still believe that many things happen in the psyche and that very often the psyche manifests itself physically. The life of a Vodu adept is not a calmly-flowing river. The individual recognises himself in the community and the community recognises itself in the individual. Incidentally, a proverb says that “If there’s a single redhead in the village, the village will be known as the village of redheads”.

A consultation for an illness may require the individual to be reconciled with his brother, his sister, or any family member, or even to reveal the problem of a friend or of an absent family member. This inconsequential ritual of being reconciled to a family member necessarily reunites the family in seeking to maintain solidarity.

Consultation may reveal that the individual covets someone else’s wife: it may just be a fantasy in his mind. The ritual may require him to leave the village, or do any sort of thing to teach him that taking someone else’s wife destroys the community: disorder in the family, shame, quarrels, even altercations between two clans. On top of that, legend has it that an adulterous couple remained stuck together and could only come apart in the market place; another says that a man maintains a continual erection until his penis reaches his knees. Whether or not such legends are true, they help reinforce the taboo concerning other men’s wives.

I don’t mean that among Vodu adepts no one takes another man’s wife, or that there is no adultery. But if you know in advance the shameful and traumatic procedure to remedy the affront, you think it through thoroughly before taking the path of adultery. Refusal to make reparation often leads to divorce: the wife abandons the conjugal hearth; the husband repudiates his wife. Now, among the Aja-tado, it is not just two persons who get married, but two families, even two villages. In order not to break up two or more families, or villages, the guilty who refuse to make amends for their sins exclude themselves, or are automatically excluded from the extended family.

Vodu Cosmogony

After reading Michel Onfray, I now have misgivings about explaining to a Westerner that Mawu (the Supreme Being) corresponds to the Christian God or the Muslims’ Allah. I feel that the West has suffered a religious trauma since the Emperor Constantine legitimated Christianity politically in June 313 with his Edict of Milan, a Christianity that he used to establish his expanding empire. Everyone had to believe in the Christian God. Believing in the Christian God, however, obliges us to renounce our own convictions, whatever they may be.

Besides renouncing our Ancestors, the Christian God also demands a renunciation of Nature and the environment with the promise of a “Heaven in the sky” (only after our death).

For the Vodu adept, the environment (including human beings) represents the multiple materialisations, the infinite terrestrial missions, of the Supreme Being. Thus, we see that the Supreme Being, Mawu, cannot be compared to the Christian God, because the Christian addresses his God through transcendent contemplation whereas the Vodu adept addresses Mawu by using and harmonising with his environment. Consequently, telling a Westerner that Mawu is equivalent, as a term, to the Christian God or to the Muslims’ Allah does not strictly mean anything. Not only will the Westerner think he is a God one must believe in, but also – and worse still – we refer him back to the traumatic memory of his Ancestors. From that point, no further objective communication is possible.

Let us replace the word “religion” with “spirituality” and let us call the Supreme Being by the name he is given by the multiple ethnicities of Black Africa. That will at least give us the possibility of translating the term or word with popular etymology and understand the practical meaning of these names or terms. Every proper name in Black Africa is conceived with an absolute meaning.

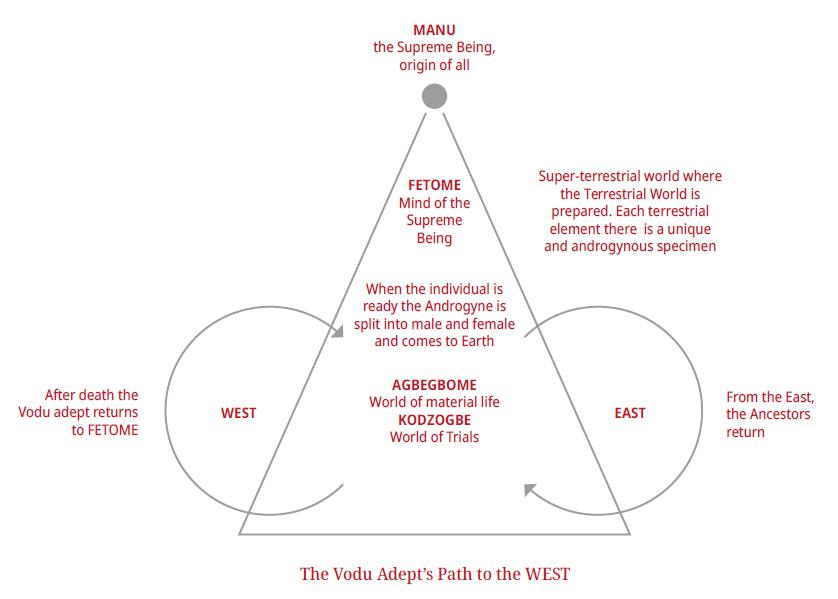

Vodu cosmogony is both simple and complex. As we shall see, it is difficult, or even impossible, to conceive of Vodu cosmogony except in a pyramidal form. The pyramidal form is inspired by the fact that the Fa myths present the Supreme Being with innumerable children as unique but androgynous specimens in timeless space; each specimen splits into male and female before coming to earth. A father at the top, unique androgynous children of each species, and a multiplication at least by two. This is the origin of my pyramidal conception of Vodu cosmogony.

I propose a Vodu cosmogony starting from Fa allegories. Fa or Ifá is a divination geomancy and a geomancy of creation. I also think that Fa is the Word that communicates between the invisible and the visible; as William Bascom says: “Ifá Divination, communication between God and men”. Fa is also the encyclopaedia of Vodu. The keys of the creations of all types of Vodu are to be found in Ifá myths and allegories. Furthermore, all Vodu temples and the various priests of the multiple Vodu deities always call on Bokon (Bokônô, among the Fon, Babalawo among the Yoruba) to communicate with their Vodu entities.

I think we can accept that this cosmogony is imaginary. Not because it doesn’t exist, but because the Supreme Being and his initial manifestations are conceived in a world beyond time, Fetomé, before materialising on a terrestrial level, and also because the conception or description of this cosmogony is open to the poetic fantasy of those who conceive it. Again, we can accept as imaginary the iconographic portrayals of the four basic manifestations of the Supreme Being (fire, air, water and earth), owing to the skill of artistic intervention. The difficulty in Vodu cosmogony lies in the fact that the invisible has to be translated into the visible, making more or less material what is conceived in a world beyond our time. My visual conception of Vodu cosmogony cannot claim to be unique or the best. Its merit lies in its inspiration by the allegories and myths of the Word of creation and communication that is Fa.

Vodu cosmogony moves on three levels: Mawu, Fetomé and Agbegbomé.

Mawu (Maou)

Although I know of no Ifá myths or allegories that speak of Mawu’s birth, in them he always acts as a father, the begetter of all the children in Fetomé. Mawu intervenes directly with his children to judge, make order or to separate them in the event of conflict, or else to demonstrate the birthright of those who deserve it. His children have direct recourse to Him to ask for advice or remove their doubts.

Certain Beninese scholars claim that Mawu (Maahu in the Fon language) is paired with Lisa. Lisa is the mystic name of the chameleon. These same scholars maintain that Lisa is the Husband and Mawu the Wife.

For me, such allegations are gratuitous and baseless affirmations, since their authors provide no explanation, still less any appearance of a demonstration. On the last occasion, in February 2017, that I heard this gratuitous affirmation, the author, a Beninese, distributed the drawing of a new moon and of a chameleon, taken from the Internet, without any hint of an explanation or demonstration.

Mawu always intervenes as father of all his children. No myth or allegory states his sex, but all concur in placing Him at a height from which He descends to meet his children. All myths and allegories unanimously present him as a Father.

According to popular etymology, the term Mawu comes from the phrase “Améa e wu”, ‘this Being surpasses’. The Fons say Maahu (Mèdé ma hu), ‘none can surpass Him’. Whether in Ewé or in Fon, we may feel authorised to translate Mawu or Maahu literally as “Supreme Being”.

The translation of “Supreme Being” is confirmed by incantations in honour of Mawu. Any African name can be explained by its matching incantations.

Indeed, during a prayer, having invoked the different deities and the various disembodied Ancestors, known and unknown, Vodu priests lastly invoke Mawu as follows: “Mawu Ségbo Lisa, Ata kokodabi, bé dzèna vônô, bé yé nu aha lé Eku shi xé féa nè”. Literally, in popular etymology, this incantation means: “Supreme Being, Ancient Soul with multiple materialisations, Omnipotent and Eternal Father, say that He has drunk at the inn of Death and has settled the bill”. As we see, the very name of the Supreme Being is itself an entire programme.

“Sè” translates as soul or spirit. “Gbo” means old or ancient. “Lisa” remains as the mystic name of the chameleon, but whenever a myth refers to Lisa, it is invariably translated as “multiple behaviours” or “multiple colours”. Consequently, the term “Lisa” in the Mawu incantation is a qualifying term or adjective meaning “multiple materialisations”. In any case, no Fa or other myth or allegory gives Mawu the role of husband. Modestly, I continue to seek the Fa sign that hints at a spouse for Mawu.

During rites, the priests may be heard naming the Supreme Being indifferently as “Mawu Ségbo Lisa” or “Amétô Lisa”. “Amétô Lisa” can be translated as “Father of many changes”, or “Father of multiple materialisations”.

Ultimately, Ifa allegories and myths confer on Mawu, the Supreme Being, the role of father; the Being through whom everything exists. Not only does he always descend from on high to meet his children, but also neither myth nor allegory places anything before Him.

Fetomé

Myths and allegories present Fetomé as a world beyond our time, a supernatural world. It is also called “Efè”. The term “Efè” is often used to designate the place where disembodied souls go. Some conflate this term with the city of Ilè-Ifè, the mythical city in Nigeria, among the Yoruba. Although there is no Fa sign that speaks of Ilè-Ifè in the allegories, Ilè-Ifè, the mythical city, is still today a major centre of Ifa geomancy. The term “Tomé” means city, town or world. We may add that the city of Ilè-Ifè is located on the migratory itinerary of the Aja-Tado. It is from there that they departed to reach Tado on the present-day border of Togo and Benin, before settling definitively on the West Coast of Africa.

The Fa myths and allegories all start with “At Fetomé, such-and-such a thing happened …”. Certain signs indicate clearly that you have to pass through Fetomé to reach Agbegbome, the terrestrial world. The whole terrestrial environment, including the human, is found at Fetomé as a unique and androgynous prototype. There is a single spitting snake, a single python, a single river … In short, every terrestrial species is a child of Mawu at Fetomé. We might say that all the species are there on the same footing of equality, because each species acts like a human being. But nowhere is it stated that at Fetomé there is a Man or a Woman. However, the Viper could be the wife of the hunter, the partridge that of the farmer: any species can be the wife or spouse of the other. Things become more complex if one says, for example, that “At Fetomé, the eye, the ear, the mouth and the nose are children of the same mother …” Who is this mother? Nowhere is it indicated. Or yet again, “At Fetomé, the vagina is a merchant, the penis and testicles are farmers …”.

However, all the signs that speak of the journey from Fetomé to Agbegbomé, the earthly paradise, allude to a stopover at Edu-Legba (the collective Legba), the guardian of the gate between the two worlds, to decide on the sex of the individual, his or her destiny and earthly mission, and to perform propitiatory rituals. This last point leads me to say that Fetomé represents a world in gestation, a world in the bud, the memory of Mawu. On consulting the Fa, what the allegories and myths say about Fetomé pertain to the consultant according to the priest’s interpretation. The gestation or budding of the world spoken of by the allegories bid me to propose that Fetomé is the memory realm of Mawu in which the terrestrial world is prepared and that each single specimen there is androgynous, and lastly, in coming to earth, at Edu-Legba, the guardian of the threshold, as each individual or species passes, attributes a physical or apparent sex. At the same time, certain rituals – and especially those of Mamiwata (the individual’s spiritual spouse) force me to say that, among Vodu adepts, each individual bears within him/herself a part of the opposite sex of his/her own apparent sex.

When someone dies on earth, in the Ifa language we say that he has left for Fè (Efè, “E yi Fè”), understood as “E yi Fétomé”.

In short, Fetomé not only represents a supernatural world or the memory of the Supreme Being where the world-to-become is prepared, but also that when one dies on earth, one goes back there. Seeing that at Fetomé one is called to come into the world, the deceased who goes to Fetomé will return to Agbegbomé, the earthly paradise, whence an initial idea of reincarnation amoung Vodu adepts.

Agbegbomé

“Agbé” means living, life, material, materialised, physical, visible, touchable.

“Gbomé”, as stated above, means world, town, circle.

Popular etymology thus translates Agbegbomé as “World of material life”. We also say “Kodzogbé”. This last term gives a deeper meaning to the third stage of Vodu cosmogony:

– “Kodzo” means judgement, trial

– “Gbé” or “Agbé” means life and, at another level, also ‘actual’, ‘present’.

Again based on popular etymology, “Agbegbomé” or “Kodzogbé” is translated as the terrestrial world or the world of trials.

From these literal explanations, we may deduce that the terrestrial world of the Vodu adept is a world of trials, a world in which life materialises. The word ‘trial’ should here be understood as ‘difficulties’, ‘temptations’, ‘sufferings’. I am tempted to say that, for the Vodu adept, neither hell nor purgatory exists after death. Everything happens here below. This is why reincarnation is conceived, in order to improve, each time, the terrestrial mission of the Supreme Being that it constitutes.

Agbegbomé is material well-being, but not isolated. It is intimately linked to Fetomé, the origin of the material world, the thought or memory of Mawu. When the Vodu adept dies, he returns to Fetomé, whence he will come back to the world to continue the mission of material realisations of the Supreme Being that he constitutes.

On Earth, the Vodu adept devises certain concepts and/or rituals that bind him to this supernatural world, which I also term the physical world:

– The Fa or Ifá is the word by means of which the Supreme Being shapes your present incarnation. The incarnated word incorporates the essence of your potential for materialisations, the fields in which you are best prepared for success in this life.

The terrestrial world of the Vodu adept is a world of trials, a world in which life materialises.

– The head, “Etá”: when your head has to be stabilised or established (materialised), it creates disorder in your head: this can even become madness. Lack of a head also means that your plans will not succeed, that you have no precise goal, or even that your head is too full, but lacking any order. Whatever one says, in every culture in the world, the head constitutes the essence of a human being’s life. Now, the Vodu adept knows that he is a terrestrial mission of the Supreme Being. If he lacks a head, how can he achieve this mission? So fashioning a head in the form of an anthropomorphic statuette of clay becomes a container for himself, a mirror of himself. It is a tool that allows the initiate to bind himself to the psychic, whether individually or collectively: it is what I also call autosuggestion.

– “Essé-Dzôtô”: this further materialisation of the psychic world of the Vodu adept takes infinite shapes. It is his/her spiritual double. It contains not only the initiate’s androgyny, but also his past incarnations that influence his present incarnation. I have the impression that “Essé-Dzôtô” allows us to draw on the consequences of previous incarnations so as to achieve our present life as best we may.

The rituals binding the Vodu adept to his past lives, which I have attended or practised, lead me to suggest that, for the Vodu adept, one is often reincarnated in the same family lineage, albeit not necessarily. A woman can be reborn as a man, a White can be reborn as a Black, and vice-versa. It is not a question of a material or physical reincarnation. It is actually more a question of a psychic reincarnation, a breath from the Supreme Being that continues to develop in terrestrial matter. Whatever the consequences of former lives, the priest must perform the proper and necessary rites to improve the applicant: such improvement is merely the pursuit of the terrestrial mission that the Vodu adept knows is his.

Explained in this manner by Tôbokô (the father-initiator) Amétamé Abianba, at Akamé in Ghana, reincarnation makes me ask myself – the man of science – the following question: Isn’t reincarnation quite simply the evolution of the world, as discovered by geologists, anthropologists, physicians and other scientists working on the origins of our Earth?

Vodu Cosmogony: a Supreme Being, Mawu, the Endless and Omnipotent Father, conceives his children as unique androgynous prototypes at Fetomé, a supernatural world. When the children are ready, meaning ready for Fetomé, they pass on to the Guardian of the Threshold, Legba, to re-enter the terrestrial world, Agbegbomé. During this halt, the Guardian of the Threshold separates the androgynous prototype into male and female, performs the necessary propitiatory rituals that will allow the Mission of the Supreme Being – which is every individual – to develop, whether well or badly, in the terrestrial world that the Vodu adept still calls the World of Trials.

Doesn’t this resemble a woman conceiving a child until it is born? The question, however, remains the same: Is Vodu a religion? A religion of Nature?

Although we perceive the meaning of religare (the same practice that binds a group of individuals to the same sacred being), here’s what a “non-believer” says, having read my works and observed my practices:

“To me, Vodu seems more than a religion, a philosophy of Ancestral Life. The Vodu adept communicates with the elements of Nature, but he does not worship them. Neither worship, not adoration. Nature is alive: it can be a benefactor, a nourisher, a protector, or it can call us to order. Aware of this Universal Energy (Mawu) at his disposal, the Vodu adept works (in rituals with plants), he speaks and communicates with (by means of Fa consultations) and orders his life according to the steps (initiations). The Vodu adept is aware of his place in the cycle of Life. For him, life is like a dance in which events are linked from pre-life to beyond physical death. A dance in which the Universal Energy (Mawu or “Cosmic?”) is never forgotten: on the contrary, that Energy is permanently present: invocations, chants and ritual dramas are there to help us recall…”.