- » Interview with Alain Daniélou, PRE-ARYAN SHAIVITE CULTURE: A TRADITION TO BE RECOVERED

- » Sunandan Chowdhury, East and West in Rabindranath Tagore

- » Christof Zotter, BĀBĀ KĪNĀRĀM AND THE AGHORĪ TRADITION IN NORTHERN INDIA

- » Basile Goudabla Kligueh, Vodu and Nature: The Vodu Adept’s Communion with Nature

- » Fabrizia Baldissera, Notes on Maṇḍalas, cakras, and the resilience of the circular icon in contemporary Indian imagery

Christof Zotter, indologist

BĀBĀ KĪNĀRĀM AND THE AGHORĪ TRADITION IN NORTHERN INDIA

All the images in this article are by christof zotter

Translation and adaptation by Adrián Navigante

The fascinating life of Bābā Kīnārām, the founder of the Aghorī movement in India, presented and analyzed from original Indian sources (in Sanskrit and Hindi) by German indologist Christof Zotter, who has researched the subject of Aghorīs for some years.

![The entrance gate of Krīṃkuṇḍ known as the “door of discernment” [vivekadvāra]](https://www.fondationalaindanielou.org/wp-content/uploads/text-3-image-2-1024x680.png)

The entrance gate of Krīṃkuṇḍ known as the “door of discernment” [vivekadvāra]

Kīnārām and Aghorīs, British imagination and emic sources

Bābā Kīnārām is the best-known aghorī in Northern India, associated with the most fantastic legends about the aghora sampradāya. He bears the title aghorācārya, that is, master of the aghora. This title already contains much more than a mere lexical question: it brings to the fore some important elements of the religious history of India deserving clarification.

The word a-ghora (the a being the equivalent of an alpha privativum in Greek) dates back to Sūrya’s Bridal Hymn in the Rigveda (10.84.), which states that the bride should not have a gruesome look [aghoracakṣus = ‘not evil-eyed’]. Both the Maitrāyaṇī Saṃhitā (4.5.11.) and the Śvestaśvatara Upaniṣad (3.5.) use the adjective aghorā (in the feminine) to refer to Rudra’s manifested form [tanū] as friendly and not fearful. The word is also used to refer to the fifth face of pancamūkha Shiva in the sense of ‘not-terrible/dreadful’, and is usually understood as a euphemism is this context1.

The modern noun aghorī, lit. “the one who is aghora”, is often seen as a euphemistic designation, too. A description of the ‘dreadful’ behaviour of aghorīs appears in almost every book about Hinduism. These ascetics are associated not only with Bābā Kīnārām’s heritage, but even with that of a much older group called kāpālikas (skull-bearers) and known for their marginality and norm transgression. As for instance H.W. Barrow reports, the aghorīs appear in many court cases in colonial India at the end of the XIX century, usually accused of cannibalism, necrophagy, and manslaughter2. Barrow’s source was the three-volume manuscript by E. T. Leith, “Notes on the Aghori and Cannibalism in India”. This manuscript, however, was not only based on court cases, but is a hotchpotch of information gathered also from travel reports and written exchanges with court officials, journalists and pundits.

There is no doubt that the aghorīs were an essential part of British demonology, and in view of the unreliable documents and even more unreliable reports from British authors, it is very difficult—indeed, almost impossible—to unravel facts from fiction. However, there are emic sources which tell us something different, especially when we focus on the founder of the tradition.

The legendary life of Bābā Kīnārām

According to the official sources of the kīnārāmī (followers of the Kīnārām lineage), Bābā Kīnārām was born in the early morning of the 14th of the dark half of the month of Bhādra. His father, a kṣatriya called Akbar Siṃha, was at that time 60 years old. Six days after his birth, a name had to be chosen for the child. Considering the age of Akbar Siṃha, the priest suggested giving the child away and buying him back. This symbolic act is usually carried out to protect a new-born when his father is old or when elder siblings might not survive. To this fact, we have to add the ominous date on which he was born: the 14th of the dark half-moon. The circumstances of Kīnārām’s birth and childhood point on the one hand to a certain aura of transgression and marginality and on the other hand to typical signs of an extraordinary personality associated with saintliness.

In the book Aughaṛ Rām Kīnā Kathā (edited by Lakṣmaṇ Śukla), we find the episode of Kīnārām’s reluctance to drink milk until he was initiated by Brahmā, Viṣṇu and Śiva who came to him disguised as three sages. The story of his marriage is linked with this early episode and highlights in typical hagiographic style the extraordinary insight of this man: following the traditional custom, the first marriage (arranged by his parents) took place when he was 9 years old³. Three years later, in the context of the gaunā ceremony (his second marriage), he felt the urge to drink milk and eat rice. Since milk and rice are known as a dish for widows, Kīnārām’s mother opposed his wish. But he insisted so vehemently that she had to give in. Immediately after he finished, the family received the news of the death of his wife to-be.

The young man abandoned his house shortly after the ceremony and sought a guru. He went to Ghazipur and there encountered a lay saint called Śivārām, who became his first spiritual guide. Kīnārām is said to have served him until the death of Śivārām’s wife, at which point he left him and continued his pilgrimage. Interestingly enough, some sources⁴ affirm that Śivārām was none other than Kīnārām himself, and argue that the boy known as “Kīnā”, in Bhojpuri meaning the “the bought one” (see above), received in his name giving ceremony also a secret name chosen according to his zodiac sign [rāśī]: Śivā. In any case, saints do not only encounter teachers, and the story of Kīnārām includes many other episodes in which he met people whom he helped, such as a woman from a town called Naīgaḍīh or Naīdīh whose son had been taken prisoner and flogged because he could not pay his debts. Kīnārām freed him and showed him a buried treasure to help him pay what he owed his landlord. Full of gratitude and awe, the young man became his first disciple and adopted the name Bījārām. He accompanied Kīnārām on his pilgrimages, and one day, while begging for alms in a city, they were sent to prison (as was usual with beggars owing to the law) and condemned to grind corn. Kīnārām ordered all sādhus in prison to stop working and when they did so, he beat one of the mills with his stick and shouted cal (“rotate”). At that moment, all the mills began to rotate at the same time. On seeing this scene, the navāb threw himself at Kīnārām’s feet and freed him together with all the imprisoned sādhus. Variants of this legend exist, for example in Lalita Prasad Vidyarthi’s book “The Sacred Complex of Kashi. A microcosm of Indian Civilization”, in which the main character of the story is an aughar called Kharab Das (instead of Kīnārām)5, or even in William Crooke’s essay “Aghori, Aghorapanthi, Aughar”, according to which Kīnārām frees his teacher, not his disciple⁶.

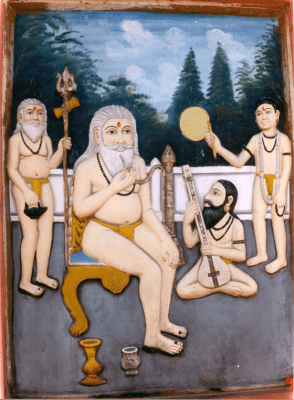

Wall painting in Śivāla (Benares) showing Bābā Kīnārām on his throne with his guru Kālūrām (left) and his disciples Bījārām and Jiyāvanrām (right)

Wall painting in Śivāla (Benares) showing Bābā Kīnārām on his throne with his guru Kālūrām (left) and his disciples Bījārām and Jiyāvanrām (right)More important than these standard hagiographical accounts are perhaps the legends showing other important elements of the Aghorī tradition: the importance of the Goddess in the life of Kīnārām, the meaning of meat in the Aghorī tradition and the tension between Kīnārām’s spiritual authority and the temporal power of kings. Concerning the first aspect, Udhayabhāna Siṃha and Lakṣmaṇ Śukla refer to Kīnārām’s pilgrimage to Hinglaj in Beluchistan, where he lighted the ascetic fire [dhūnī]and meditated for a couple of days on the banks of the Aghor river⁷. During his meditation,

Kīnārām was regularly visited by a woman who brought him food. When he asked her name, she revealed herself as the local goddess Hiṅglāj Devī. She told him to go to Benares and meet her there at the spiritual centre of Krīṃkuṇḍ in the form of a hidden yantra. This brings us to the second aspect concerning meat and social engagement (as opposed to vegetarianism and ascetic isolation).

Kīnārām established himself at Benares, following Hiṅglāj Devī’s instructions⁸. But before Kīnārām came to Benares, he went with his disciple Bījārām to the Girnār mountain in Gujarāt, where he met an old man. This man was Dattātreya, the master of siddhas, and he offered Kīnārām a piece of meat. No sooner had Kīnārām tasted the meat than he obtained the siddhi of foresight [dūra dṛṣṭi], and Dattātreya assigned him the task of transmitting his wisdom to society. At Benares Kīnārām is said to have performed miracles such as the resurrection of a dead man floating on the Gaṅgā who became his disciple with the name of Jiyāvanrām⁹.

The aghorīs have a reputation for terrible behaviour and practices breaking all the norms.

Once established at Krīṃkuṇḍ, Kīnārām received many worshippers and supplicants, including the sovereign of the new Hindu dynasty of Benares, Mansārām, who stemmed from a very influential Brahmanic family. With this episode, we reach the third aspect mentioned above: the opposition of spiritual authority and temporal power – which in the hagiographic sources is rather treated as the problem of justice. As a ruler, Mansārām was always very fond of and attentive to Kīnārām. The problem arose when he passed away and his son inherited the throne. He paid no attention to Kīnārām and ignored spiritual tasks altogether. For this reason, Kīnārām entered the palace one day with a donkey at a moment when a Vedic recitation was taking place. Since the people present began to mock him, he accused them of religious fraud and made his donkey recite the Veda. Immediately afterwards he cursed the sovereign with a lack of progeny.

But the most extraordinary episode in the life of Kīnārām was his death10. After cursing the palace, Kīnārām gathered his disciples and followers and drew on his water-pipe [hukkā]. Suddenly, thunder roared and a ray of light welled out of his head toward the heavens. His body was placed together with the yantra of Hiṅglāj Devī. All the people were very sad, but they soon perceived a hand stroking their heads from the heavens, and at that moment the voice of Kīnārām was heard, saying that whenever his worshippers were in difficulty, they would receive his help by just thinking of him11.

Kīnārām as aghorī

It is widely known that the aghorīs have a reputation for terrible behaviour and practices breaking all the norms. Although some of the transgressive elements usually mentioned with regard to aghorīs are present in the story of Bābā Kīnārām, the focus—as we have seen—lies on the supernatural powers of the saint and on his service to other people. The question remains: how did Kīnārām become an aghorī?

In the main sources about the saint, two places play a decisive role when it comes to the question of how he became an aghorī: the first is the Girnār mountain, where Kīnārām ate a piece of meat and was awarded the siddhi of foresight; the second is Benares, where Kīnārām met a sādhu who fed grains to a group of skulls at the cremation ground of Hariścandra ghāṭ. In either of these places, Kīnārām is assumed to have been initiated as aghorī. According to William Crooke, Kīnārām was first a disciple of a Vaiṣṇava pundit in Ghazipur; afterwards in Benares he met a certain Kālurām from the Girnār mountain and was initiated to aghorapantha12. Caturvedī and Śāstrī also tell about an initiation in Benares under the guidance of Kālurām13. According to the tradition’s own sources Kīnārām encountered in both places an incarnation of Dattātreya.

The figure of Dattātreya—a syncretic deity representing the union of Brahmā, Viṣṇu and Śiva—occurs in a number of traditions as original preceptor [ādīguru]. He is simultaneously worshipped by Vaiṣṇavas, Śaivas and Śāktas and is even present in Muslim cults. It is difficult to say whether Kīnārām was initiated by a real guru belonging to the aghorī tradition at the mountain of Girnār or whether his initiation was the result of a vision [darśana]he had at the summit of the mountain. No solid conclusion can be drawn on this subject from existing texts.

Other sources point to yet another guru: an aghorī who lived at the Maṇikārṇikāghāṭ with his wife told Vidyarthi that Kīnārām had been following Rāma devotionally for twenty years; he served him, but he could not really find him. One day, Kīnārām had the idea of drinking wine. No sooner had he raised the glass than the god held his hand. Kīnārām spoke thus: “I cannot leave it as it has brought me in contact with you and thus wine is my guru”14. There are also other legends linking Kīnārām to the consumption of alcohol – which is also an important element in aghorī rituals. We should not forget that some of the legends about Kīnārām present mythological elements linking this saint to the figure of Bhairava, which is the most terrible aspect of Śiva. It is therefore not surprising that many features and figures revolving around Kīnārām have to do with atypical, transgressive and violent behaviour – without being devoid of sacredness.

- Sir Monier Williams, A Sanskrit-English Dictionary (1995).

- H.W. Barrow, “On the Aghoris and Aghorapanthis”, in: Journal of the Anthropological Society of Bombay 3.4., 1893, pp. 197-251.

- In some other accounts, he is said to be twelve years old when he married (cf. among others, Paraśurām Caturvedī, Uttarī Bhārata kī santa-paramparā, Ilāhābāda 1972, p. 690).

- Such as, for example, Lakṣmaṇ Śukla, Aughaṛ Rām Kīnā Kathā, Vārāṇasī 1988, p. 18, and Udhayabhāna Siṃha, Aghorācārya Bābā Kīnārām jī, Vārāṇasī 1999, p. 31.

- Prasad Vidyarthi, The Sacred Complex of Kashi. A microcosm of Indian Civilization, Delhi 1979, p. 302.

- William Crooke, “Aghori, Aghorapanthi, Aughar”, in: The Tribes and Castes of the North-Western Provinces and Oudh, Volume 1, Delhi 1999, p. 27.

- The river is called Aghor or Hiṅgol, and the place where Kīnārām meditated is the westernmost śākta pīṭha (main shrines and pilgrimage destinations related to Shaktism in the Indian subcontinent).

- Lakṣmaṇ Śukla, Aughaṛ Rām Kīnā Kathā, p. 24 and Udhayabhāna Siṃha, Aghorācārya Bābā Kīnārām jī, pp. 67-68. Cf. also Lakṣmaṇ Śukla, Aughaṛ Rām Kīnā Kathā, pp. 27-28 and Udhayabhāna Siṃha, Aghorācārya Bābā Kīnārām jī, pp. 39-40.

- Cf. Dharmendra Brahmacārī Śāstrī, Santamata kā sarabhaṅga-sampradāya, Paṭnā 1959, p. 147.

- Lorenzen explains that supernatural episodes accompanying the death of saints are no exception but rather the rule (see David Lorenzen, “The Life of Nirguṇī Saints”, in: Bhakti Religion in North India. Community Identity and Political Action, Albany 1995, pp. 188-189).

- Cf. Lakṣmaṇ Śukla, Aughaṛ Rām Kīnā Kathā, pp. 76-79, and Udhayabhāna Siṃha, Aghorācārya Bābā Kīnārām jī, pp. 110-115.

- William Crooke, “Aghori, Aghorapanthi, Aughar”, in: The Tribes and Castes of the North-Western Provinces and Oudh, Volume 1, p. 26-27.

- Paraśurām Caturvedī, Uttarī Bhārata kī santa-paramparā, pp. 692-693, Dharmenda Brahmancārī Śāstrī, Santamata kā sarabhaṅga sampradāya, Paṭnā 1959, p. 139.

- Lalita Prasad Vidyarthi, The Sacred Complex of Kashi. A Microcosm of Indian Civilization, pp. 226, 303).