- » Jacques Cloarec, A SHORT BIOGRAPHY

- » Essay, Adrián Navigante. JACQUES CLOAREC: at the heart of the Labyrinth

- » Testimonials: Ajit Singh / Sophie Bassouls

- » Interview: Adrián Navigante in conversation with Jacques Cloarec

- » Special tributes: Alain Danielou: The magic universe of JACQUES CLOAREC. Alberto Sorbelli: Title, Act 1, Entr’acte, Act2. Sylvano Bussotti, Impromptus Cloarec

- » Documents: Jacques Cloarec, Wisdom and Passion Impressions of the Labyrinth

TESTIMONIALS

Ajit singh: News Editor and Regional News Head at All India Radio

A black and white photo of a ‘caravan’ in my father’s personal collection introduced me to the world of two European scholars – Alain Daniélou and Raymond Burnier. About this fascinating photograph, my father once told me that Daniélou and Burnier used the caravan during their trip to India in the early 1930’s.

Daniélou, during his stay in Benares for 18 years (1936-1954), hired many local persons. My father, Kamal Singh was among them. He used to help him in his day-to-day work.

Suddenly one day, I met Jacques Cloarec, a close associate of Daniélou’s, for the first time in 1999 when he travelled all the way from Italy to Benares just to meet those who worked with Daniélou and Raymond Burnier. At that time Jacques gave me a photograph of my father with Daniélou in Switzerland, which is so precious for my entire family. This photograph unlocked a mystery that lay hidden in a metal trunk at our house. Amidst numerous paintings, I came across my father’s passport, stamped in so many countries, although my father never spoke about his travels.

In the year 2004 I approached Jacques to seek information on my father’s trips to Europe and America while working for Daniélou and Raymond Burnier. To link his work and life, I planned a book release on the first anniversary of my father’s death. Jacques responded immediately and made all the required materials for the book available to me.

I am also indebted for his help in sponsoring a painting exhibition of my father’s work in Milan and in Zurich in 2005, besides extending financial support for my prospective media studies in Canada in 2017.

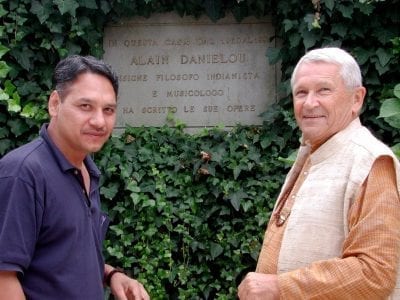

At the invitation of Jacques, I visited Daniélou’s residence at Zagarolo several times. The house, the Alain Daniélou Study Centre, located among scenic hills about 40 kilometers away from Rome is a pilgrimage, a ‘must’, for scholars and lovers of Indian art and culture.

The ambience inside the house virtually takes anyone to the India of the mid-19th century, where a classical musical instrument, Daniélou’s vīṇā, is kept beside his piano. His passion for the symbolism of Hindu architecture and sculpture is preserved in the form of so many books in his library, written either in India or in Europe. The paintings and pictures displayed everywhere on the walls are a valuable asset for any visiting scholar to these premises. Daniélou’s notations on the orchestration of a few songs by Rabindranath Tagore are a rare example of his unique musical knowledge. I am grateful to Jacques for his kind hospitality and guidance without which my understanding of Daniélou’s and Burnier’s love for India would have remained incomplete.

Jacques, as the Honorary Director of Alain Daniélou Foundation, has been for more than five decades deeply involved in promoting and preserving the cultural heritage of Daniélou. He has worked rigorously to strengthen both network and strategy, showcasing Daniélou’s philosophy and contribution to Indian art, culture, language, music across the globe. His perspectives about the entire journey of life of Alain Daniélou and Raymond Burnier have helped me know them more deeply.

After my father, Jacques is the person who has made me understand how these two great scholars played a key role in getting recognition for Indian music and Hindu architecture in the western world. Jacques narrates that Daniélou’s perfect mastery of Hindi helped him a lot in translating the Kāmasūtra, a very difficult text in ancient Sanskrit. He once mentioned in a note that he saw Daniélou working on it alone for four years with just his Sanskrit–English dictionary, beginning at the age of eighty. Jacques also gave me an insight into Daniélou’s musical training with Shivendranath Basu who, not belonging to the musicians’ caste, refused to play in public or to be paid.

I love Jacques’s way of practicing Shaivism, following Alain Daniélou who always considered himself a Hindu and declared India to be his true home. Alain Daniélou wrote on Hinduism, “The only value I never question is that of the teachings I received from Shaivite Hinduism which rejects any kind of dogmatism, since I have found no other form of thought which goes so far, so clearly, with such depth and intelligence, in comprehending the divine and the world’s structures”.

Jacques’s rudrākṣa with a Shiva liṅga around his neck shows devotion to ‘Shaivism’ and respect for his mentor. My family is fortunate to receive his blessings every year on the occasion of Mahā Śivarātri. I wish Jacques a long and healthy life!

Sophie Bassouls: Photographer

To define him, I would say that he’s young and has never ceased to be young.

His white hair counts for nothing: age seems not to overwhelm him; no wall confines him.

Young, always young: the years have not managed to transform the “sprite” – as my uncle used to call him – into an old gentleman.

If you seek him here, he’s somewhere else. Can he be the “furet qui court qui court” (the ferret, it runs, it runs)?

He goes from one house to another. With and without my uncle. This includes Zagarolo, Berlin, Venice, Lausanne, Paris, Delhi, and – always – Concarneau.

The countryside, the mountains, palaces, monasteries, the sea, and any other place as chance may take. Would he be looking for his double without ever finding him?

He goes here and there, time for a stopover of which he alone knows the priorities and schedule.

In Paris, Jacques lives in front of the Musée Pompidou, witnessing beneath his windows the perpetual bustle of the esplanade, enjoying improvised concerts, also walking along the banks of the Seine, organising dinners for his most faithful friends, taking part in society events and … that’s enough! Off he flies. To Lausanne, perhaps?

There, in solitude, he walks in the gardens of the Hermitage. You have to follow him on the steep sidepaths, (I know what I’m talking about!). Sometimes, he needs nothing. He just meditates, withdraws from the world and (happily) he returns to it, letting nothing appear of any worries that may trouble him.

The Alain Daniélou Foundation, which he tenaciously and constantly energises, keeps him busy every day.

I imagine, and doubtless I digress, that his time is divided between an anchorite’s dream and that material reality that he knows how to deal with so effectively.

Jacques Cloarec with his lenses, 1999

Jacques Cloarec with his lenses, 1999Photo: Sophie Bassouls

Life at Zagarolo (without of course mentioning the work and attention needed by Alain Daniélou Foundation) gives him the opportunity of leading several lives at once. He is a farmer, a winegrower, he wanders round the estate before dawn, followed by his dogs, Abruzzi watchdogs, he monitors the trees, examines the vineyard. Each year the grape harvest follows strict oenological rules, the grapes trodden by a young man as at the time of Hadrian, who will give his name to the year’s vintage.

Then he becomes an architect: I have seen the Labyrinth grow from year to year, become more complex (Labyrinthe oblige), a pavilion will rise in the full sun; a swimming pool will vanish and another be dug.

The style of living there has no equivalent. As often as I return, it is with the same pleasure each time. A delightful freedom is the rule for everyone and guests need never worry that they might be invasive or boring. The master of the house maintains his role, while adopting an apparent casualness. It is not by chance, however, that the menus suit everyone’s dietary taboos, or flowers are placed in the rooms, or the library is left open and accessible.

The Labyrinth is also a strange phalanstery that includes Sylvain, Ken, Giorgio, Maurizio, Adrián, like so many living limbs, each with his own work and links, with his own personality and space for all his fantasies.

I have spent very amusing times at the Labyrinth. One dresses up, wears things without taking the place or season too much into account. A sarong will be fine for watering the garden, an Indian tunic for dinner, under a vault of kiwis.

On one occasion, a Scotchman will pose with his dogs, or an Egyptian evening will be improvised, or a musical one. One day a beard grows, then disappears; behind dark glasses, he takes on the air of a Calabrian bandit.

Above all, do not think that doing everything that he undertakes so seriously makes him a serious person! That would leave out all his fantasy, his liking for dressing up, his jokes, his collection of bizarre slips of the tongue, or the changes of language that he gleans here and there, or even invents.

Jacques Cloarec in 2003

Jacques Cloarec in 2003Photo: Sophie Bassouls

Of his Breton childhood and the gavottes danced to the sound of the bagpipes (not the most melodious instrument on the planet), Jacques has maintained a feeling for festivals, dance, a little mad like all the Bretons, but fairly wise too.

I see my friend Jacques as a shy person. By way of reaction, he will shake it off with some great theatrical gesture to accompany the bonfire in the gardens, or the plan to restore a ruin, which he wishes to bring back to life.

Is he happy in his kingdom?

Is he “comme le roi d’un pays pluvieux, riche mais impuissant, jeune et pourtant très vieux” in Baudelaire’s poem (like the king of a rainy country, wealthy but powerless, both young and very old)?

His sojourns in far-off monasteries, his vagabond moods, his longing to be elsewhere, his appeals for solitude, what do they tell us?

One day he may arrive, brandishing the book he has just finished, in order to solicit our questions.

Happy birthday, dear Jacques, the burden of years seems not to weigh you down: long may it be so !

When I saw Jacques Cloarec for the first time, certainly around 1981, it was in Paris. He was a photographer, a hat that suited him at that time, amongst all those that a man like him can wear according to whim and the opportunities of life. A magnificent photograph, portraying a naked youth, life-size, was on the wall and the same youth, albeit clothed, was also there. It was still a very Puritan time, but in that house nothing was taboo, and certainly not the beauty of a boy’s body.

Jacques worked a great deal on his photos, arranging sets in selected locations.

One day he wanted to convert me (I’m also a photographer) to the square format and he lent me his Hasselblad, that mythical camera. I made a few attempts, but couldn’t get used to the square format.