- » Jacques Cloarec, A SHORT BIOGRAPHY

- » Essay, Adrián Navigante. JACQUES CLOAREC: at the heart of the Labyrinth

- » Testimonials: Ajit Singh / Sophie Bassouls

- » Interview: Adrián Navigante in conversation with Jacques Cloarec

- » Special tributes: Alain Danielou: The magic universe of JACQUES CLOAREC. Alberto Sorbelli: Title, Act 1, Entr’acte, Act2. Sylvano Bussotti, Impromptus Cloarec

- » Documents: Jacques Cloarec, Wisdom and Passion Impressions of the Labyrinth

Essay : JACQUES CLOAREC: AT THE HEART OF THE LABYRINTH

Adrián Navigante Alain Daniélou Foundation Research and Intellectual Dialogue

Jacques Cloarec inherited the whole of Alain Daniélou’s philosophy of life and distilled it according to his own personality. While Alain Daniélou is the (shaivite) non-conformist who pushed his free thinking beyond the limits of accepted conventions in order to create something new, Jacques Cloarec is the (vishnuite) preserver of his work. His devotion, rectitude and diligence have enabled the Labyrinth not only to survive as a rare exception of harmonious interaction between different beings (animal, human, divine) in the world of today, but also to adapt to new times and to expand its magic, inspiring people from all over the world. This essay tries to do justice to Jacques Cloarec’s perspective in the continuation of Alain Daniélou’s work.

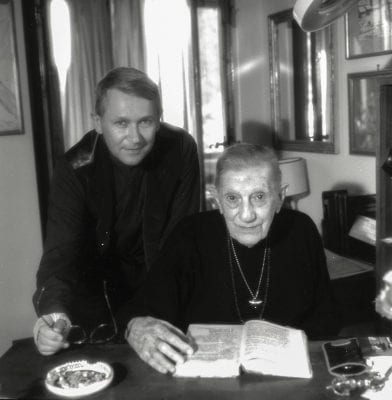

Jacques Cloarec with Alain Daniélou in 1993 while translating the Kāmasūtra

Jacques Cloarec with Alain Daniélou in 1993 while translating the KāmasūtraPhoto: Angelo Frontoni

1. Journeys

“To depart”, writes Jacques Cloarec in his Journal Asiatique Insolite (2009), “is to learn that the world is not one” . By ‘depart’ he means ‘travelling’. Travelling means opening oneself to the otherness of a foreign culture, decentring oneself as Alain Daniélou did quite early in his life, venturing abroad in search of his own freedom. Travelling is a form of extraversion that expands the horizon of one’s worldly experience in learning more about diversity, questioning one’s own convictions and beliefs to grow out of them. But, as Daniélou said, there is another journey that is not usually so easily spoken of: the inner journey² . The appropriate metaphor in that case – at least for Alain Daniélou and for Jacques Cloarec – would be the Labyrinth, for the Labyrinth encompasses the whole universe to the same extent as this universe is reflected in the microcosm of the individual. There is consequently an external departure and an internal departure, which are different but not necessarily contradictory, since intelligently accomplished extraversion is also a form of looking at oneself deeply and re-discovering oneself through a broader understanding of the world. Introversion, on the other hand, is a path towards the centre. I would almost call it ‘centroversion’, borrowing this term from the Jungian psychologist Eric Neumann, were it not for the impossibility of locating the centre. Because the centre of the Labyrinth is simultaneously ‘everywhere’ and ‘nowhere’, being at the centre of the Labyrinth is not fixing a point or standing on an eminence with a view of the whole, but rather flowing through the energies that fill the place without the slightest resistance, flowing as if one were at the heart of those energies. I have a feeling that Jacques Cloarec has reached not only his eightieth year of age, but also something that is far beyond mere biology: he has reached the centre of the Labyrinth and pulsates in tune with the heart of it. Eighty years is, as Daniélou said jokingly using the French expression, fourscore, or four times twenty. But eighty years is also twice forty, eight times ten, sixteen times five, and all the possible combinations of a life reflected in the intensity of an accomplished here and now. It is from this enigmatic centre and with a light-hearted regard to infinity that Jacques Cloarec watches over and nurtures Alain Daniélou’s work, preserving and expanding its essence. It is out of that feeling that I am writing the lines which follow.

2. The disciple

Jacques Cloarec tends to disappear behind his work, and may leave the impression that he does not even recognize his own merit: he constantly speaks of his maître, and makes it quite clear that his life-task is to preserve Daniélou’s work and to make it accessible to those who wish for a better understanding of the complexity of the world. It should be borne in mind that Jacques Cloarec is Alain Daniélou’s disciple, as he clearly states in his essay Sagesse et Passion: “he [Alain Daniélou]is my Guru, my master, in the exact sense that this term is understood in India. […]But this became clear to me only after his death”. Alain Daniélou’s quality as a guru seems to have been imperceptible, since Jacques Cloarec did not notice from the very beginning the depth of the influence he was undergoing: his life changed radically when he met Daniélou in 1962, but the transformation was a process, and it dawned on him little by little with the passage of time. Just as a good leader is one whose exercise of power is not noticed by his/her subordinates, a good guru does not exhibit his power of influence, because the work itself speaks and permeates the spirits of those around. Similarly, we could ask ourselves: What is, in fact, a good disciple? I would venture to say: one who learns permanently, not only from his guru but also from life, and who remains humble enough not to slip from intelligence into idiocy, from subtleness into vulgarity. Arnaud Desjardins once said, in talking about his guru Swāmī Prajñānpad, that people should learn more about being good disciples instead of wanting so much to become gurus. He defined himself as a disciple and affirmed this status against people who called him a guru. The same applies to Alain Daniélou, who always emphasized that the true guru was not him, but Swāmī Karpātrī. In saying this, he was showing that the first sound lesson is not to identify your ego with the contents of what you learn, as many so-called ‘traditionalists’ do, claiming to possess the key to the universe merely because they have read esoteric books and repeat commonplaces (as often as not without even understanding them).

Being at the centre of the Labyrinth does not mean dying or becoming a god, but rather attaining a practical wisdom that embraces the human condition with all its imperfections, rather than rejecting it.

Jacques Cloarec at the centre of the Labyrinth: What is the sense of that expression? Being at the centre of the Labyrinth does not mean dying or becoming a god, but rather attaining a practical wisdom that embraces the human condition with all its imperfections, rather than rejecting it. Jacques Cloarec’s philosophy is so similar to that of Alain Daniélou, that I am rather compelled to say a few words on the latter in order to contextualize. Let’s begin, then, with some generalities. I think it is wrong to believe (like some pious Indians or some Indianised Westerners) that Daniélou’s philosophy is essentially related to the Brahmanic ideology of India. It would also be wrong to believe that the foundations of Daniélou’s philosophy are to be found in the mainstream discourse of that amazingly complex theistic trend of the Indian Subcontinent called ‘Shaivism’. This is perhaps what some readers might wish to affirm to avoid the effort of delving into the work of a myriad personality like Alain Daniélou. There are many forms of Shaivism (from the aesthetic-metaphysical system of the Kaśmirī elite to the subversive sect of the Lingāyats), and Brahmanic ideology has not fallen from heaven as a totally unified corpus of doctrine (it suffices to compare the Weltanschauung behind the abstract philosophical speculations of Rig Veda with the magic and demonological practices of forest asceticism in Atharva Veda). Hinduism is not a religion that can be summarized in a sacred text and reduced to a set of practices to be universalized after the fashion of Coranic schools. It does not work that way, just as it does not work to call Daniélou a yogi, a saint, a perennialist or a perverse mind. The more one knows about Hinduism, the more one realizes how multiform and diversified it is, to the point where even the word ‘Hinduism’ turns out to be an abstraction that in no way corresponds to the myriad of living religious traditions on the Indian Subcontinent. The more one knows Daniélou, the clearer it becomes that the figure that expressed his life was the paradox. In particular, the concept of ‘tradition’ is problematic in the singular (and even more when written with a capital letter). There are different traditions, even religious and esoteric ones, and the medium as well as its dynamics is not accurately called sanātana dharma but rather sampradāya. It is a beautiful idea to think – in the words of Fritjhof Schuon – of an underlying unity of all religions, and Daniélou also liked this idea. But such a hypothesis is far removed from the concrete practice of living traditions, whose processes and experiences are far from being the same (a Theravāda Buddhist does not live the same life as an Aghorī, and the practices of a Tantric priest in Assam are not exactly those of a Benedictine monk at Subiaco). So, when Daniélou said that he adopted Shaivism, one should bear in mind that he had a specific idea, gathering different aspects of this complex phenomenon in order to extend the term even beyond the religious framework of India. Daniélou’s idea of Shaivism was no dogmatic block (he was too creative for that), but rather a construction of different aspects based on what he experienced and learned during seventeen years in Benares, and on what he later exhumed, researched and artistically restored: the pagan substratum, the most ancient religious layers of the European civilisation (also multiform) that flourished before Christianity. In this sense, the pseudo-scholarly accusation that he superficially concocted Etruscan mythology, Dionysian religion, Mithraic cults and Shaivism is as ridiculous as the pseudo-traditionalist objection focused on the ‘primordial Tradition’ that he is claimed to have betrayed when he eroticized religion and denied the value of initiation. It suffices to remember that Eros is part and parcel of Shaivite religion, as anyone can appreciate who makes the effort to delve into the mythology of Shiva and some Puranic sources, whereas the gesture of relativising initiation (as Daniélou does in Le mystère du culte du linga 5 ) is a healthy prophylactic against sectarian fundamentalism. Daniélou was, first and foremost, radically anti-dogmatic and anti-fundamentalist, as is Jacques Cloarec. If they battle against anything, one could say that they battle against the fear of freedom.

3. Inheritance

What did Jacques Cloarec, the good and loyal disciple, adopt from Daniélou’s philosophy of life? I would say with utter conviction: the whole of it, but he distilled it according to his own personality and background, so that the ‘wholeness’ in question looks somewhat different. Whereas Alain Daniélou was immersed in Indian philosophy and religion, Jacques Cloarec was a passionate researcher of Brittany’s pagan substratum and he has always felt religiously linked to Nature almost in the same way that Daniéliou describes the animistic substratum of religious experience – which resembles the type of living religion he discovered as a child. Jacques Cloarec has understood fully that Daniélou’s almost irreconcilable praise of the ancestry of Shaivism (which he traced back to the Indus Valley civilisation) as well as of the Brahmanic institutions codified in the corpus of Dharmaśāstras had a practical reason and aim in life. Shaivism is a religion of Nature and therefore a clear example of the Hindu ‘pagan’ spirit, easily adopted in a place like Alain Daniélou’s last refuge in Italy, the Labyrinth at Zagarolo. After Daniélou’s death in 1994, Jacques Cloarec cultivated a true pagan art of living, observing rituals linked to natural cycles (such as solstice and equinox bonfires), decentring humans from the womb of Nature with the aim of giving greater visibility to animals, plants, insects and other non-human beings whose dignity has been ignored for centuries – at least in the Western world. The hierarchical order of classical Hinduism (based on a mythical model of the caste system appearing in the famous puruṣa-sūkta of the Rig Veda 6) presented, on the other hand, two very interesting aspects both for Alain Daniélou and Jacques Cloarec: a balanced distribution of power (brahmans in charge of knowledge, kṣatriyas in charge of weapons, vaiṣśyas in charge of money and Śudras in charge of land) and a very flexible system for the integration of foreign cultures and the simultaneous preservation of identities. As Alain Daniélou writes in his essay Le système hindou des castes: “The caste system in India was created to enable very different races, civilisations, cultural or religious institutions to survive and coexist” 7. As curious as it may seem to the modern Western reader, Jacques Cloarec does not relate the caste system to oppression (although he recognises its problems, especially through the history of modern India), but rather to anti-colonialism and respect for the other. Severely criticised restrictions are not something he ignores but, like Daniélou, he poses the practical question as to how a society can survive harmoniously when human beings tend to an egotistic appropriation and unmeasured expansion of personal power. The answer seems to be, at least for Jacques Cloarec, hierarchical politics based on recognizing the dignity of each being and on a fair distribution of tasks. That is the way the Labyrinth works, and it is most probably because of this ‘conservative’ rule that it has been preserved for decades, even at times of serious imbalance.

However, it is important to remember that Jacques Cloarec is the disciple of a man who strove throughout his life for freedom and permanently questioned orthodoxy. This is enormously different from remaining within the safe boundaries of orthodoxy and orthopraxy (which has not been the case with Jacques Cloarec, either). We should therefore ask ourselves: What does Alain Daniélou mean when he says that he adopted the orthodox Hindu standpoint in his own life? Here many readers might fall into the trap of believing that he wished to represent traditional Brahmanic values (since Swāmī Karpātrī was a Brahmin) and export them to the West when he returned to Europe. Could somebody who – as Jacques Cloarec himself says – led a mundane life surrounded by artists, embarked on adventures in the underworld of capital cities from Beijing to Berlin and frequented the neighbourhood of Roma Termini so dear to Pasolini, actually fit in with the paradigm of orthodox Brahmanism? Of course not, and that is not the way in which his ‘Hindu orthodoxy’ should be understood. Alain Daniélou emphasized that part of Hindu tradition as a tool against Western colonialism. According to him, this necessary reaction took many forms, the last of which was not the British Raj, but the modern reform after Indian independence, that is, the ideologically motivated passage from a traditional, religious and hierarchically stratified to a modern, lay and democratic India. One could endlessly discuss this topic, involving not only politics but also the history of ideas and even comparative religion, but the focus should remain on the meaning of the word ‘orthodoxy” when Daniélou speaks of Hindu orthodoxy. It is the remnant of an ancient civilization in the face of which, in his view, the West has no right to impose a political form of government, a modern system of education and an institutional reform out of the mere belief that Western social life is superior to what India has transmitted over three millennia. The clearest sign of Alain Daniélou’s heterodoxy was his life: if he had remained within the strict framework of traditional Hindu orthodoxy, he would not have abandoned his music teacher Shivendranath Basu, he would perhaps have become a sannyāsin under the guidance of Swāmī Karpātrī, or he would have adopted the role of a locally trained Hindu scholar to impart the Vedic mainstream in Western universities on his return. But nothing of the sort took place. Daniélou rejected university posts, refused to wear traditional Indian clothes to look like a guru, and set up an Institute for the comparative study of music in order to eliminate the prejudices of ethno-musicology towards the value of non-European traditions. He wrote, he painted, he danced, and above all he loved beauty (bodily concrete sensual beauty, pretty much like Oscar Wilde, who paid a high price for it in the Victorian society of his time); he also extended the perception of eroticism from the restricted field of sexual practices in the human sphere to an impersonal and inexhaustible force permeating the whole universe and represented in the cosmogonic pair lingam and yoni.

It is precisely this spirit that was inherited by Jacques Cloarec. Fully convinced of the irreplaceable value it contains, Jacques Cloarec has carried on Alain Daniélou’s opus. One might ask what he did exactly that was so important, since he doesn’t write books like Alain Daniélou, he is neither Indologist nor musician, and he always pointed to his intellectual limitations concerning Daniélou’s speculations about cosmology, metaphysics and religion. Well, the answer is simpler than it seems: Jacques Cloarec has kept the Labyrinth alive, he has preserved it as a place where true pagan values are cultivated, where one can live in harmony with Nature, respecting every living form, rejecting the arrogance of thinking that human beings are the crown of creation, free from prejudices (especially of the moral kind) and trying to maintain a relative autarchy in the face of the ‘outer world’. The Labyrinth is a magical place and also a community where each member seems to have a place allotted by the gods, as Daniélou writes in his Contes du Labyrinthe. Preserving this place means preserving Alain Daniélou’s work in the alchemical sense of opus. His whole philosophy of inner transformation incarnated in the genius loci and expressed in the beings (human and non-human) living there is a permanent transmutation of perception, emotion and cognition, as well as an integration of these qualities into a field of transpersonal forces. Inhabiting the Labyrinth is an art in itself, first and foremost an art of living, but also a magic art when it involves awareness of the forces dwelling there and cohabiting in harmony with them. One very important artistic expression in Jacques Cloarec is photography, from landscapes to naked bodies. Their salient feature is not mainly as testimony (as a pictorial complement to travel diaries), but to some extent related to the possibility of catching beauty at a level that is not visible in this world, something of the order of svarūpa in Tantric visualisation.

4. The preserver

Once, when I was sitting at the main house of the Labyrinth at a meeting with Jacques Cloarec, we spoke of work to be done, of the activities of the Foundation and the intellectual direction to be taken in order to do justice to Alain Daniélou’s heritage. At a certain point, the question was raised about the value of the Labyrinth and the need for activities there. I said that for me the Labyrinth is Daniélou’s work incarnated, and that the Alain Daniélou Foundation without the Labyrinth would be difficult, rather like a body without a soul. At that point Jacques told me an anecdote that confirms his importance not only in Daniélou’s life, but also in the context of the Labyrinth and the Foundation for generations to come. The death of his friend Raymond Burnier deeply affected Daniélou and he wanted to leave the place. It was Jacques Cloarec who persuaded him that the Labyrinth had to be preserved, and it was because of Jacques’ effort that Daniélou stayed there for the rest of his life. Why did Jacques Cloarec defend the Labyrinth against his own maître? It is precisely that gesture that confirms the quality of the ‘disciple’: he saw through Daniélou’s human weakness and remained focused on the trans-personal value of his work, which Daniélou himself affirmed shortly before his death. He told Jacques Cloarec that the main task from that day onwards was not to turn the Foundation into a successful institution, but to preserve the Labyrinth as a place where one lives without prejudices, in harmony with Nature and respecting all beings. Not a single day passes without these words reappearing before my mind’s eye, questioning me with regard to the activities of Intellectual Dialogue. Jacques Cloarec’s ‘discipleship awareness’ has, in this sense, outreached Daniélou’s mastery and creativity, and the opus goes on because of his loyalty and his tenacity in doing justice to it. Jacques Cloarec has been a benevolent ‘Vishnu’ in a Shaivite context: his role has always been that of the ‘preserver’ in the microcosm of the Labyrinth. His being at the centre transmits a sense of right and orientation, which the other members of the Labyrinth must be aware of, to accompany him and pursue his efforts as best way we can.

- Jacques Cloarec’s journals are unpublished and have therefore no pagination. I am grateful to have had access to some of his texts in order to gain important insights into his personal life and interests.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Le Chemin du Labyrinthe, Lausanne 2015, p. 323.

- Jacques Cloarec, Sagesse et Passion, in: Ricordo di Alain Daniélou, Firenze 1996, p. 4

- Frithjof Schuon, De l’unité transcendante des religions, Paris 1979.

- “After all, initiation is a way of integrating yourself into a system, that is all. It is far from being something that changes your life” (Swami Karpâtri /Alain Daniélou, Le mystère du culte du linga, Robion 1993, p. 25).

- Cf. Rig Veda, 10.90.

- Alain Daniélou, La civilisation des différences, Paris 2003, p. 47.

- Jacques Cloarec, Alain Daniélou et les Castes, in: La civilisation des différences, Paris 2003, p. 176.