” The first duty of man is to understand his own nature and the basic elements of his being,

which he must fulfill to the best of his ability “

Alain Daniélou

Index:

- » Alain Daniélou and India: A Path of Integration and Freedom, Adrián Navigante

- » Phenomenology of Religion as Religion of Life: A Programmatic Introduction, Rolf Kühn

- » Vedānta and Holistic Health, Basant Gupta

- » Towards New Metaphors in the Description of Tonal Relations, Danel Cove

- » The Flowing Goddess, Gioia Lussana

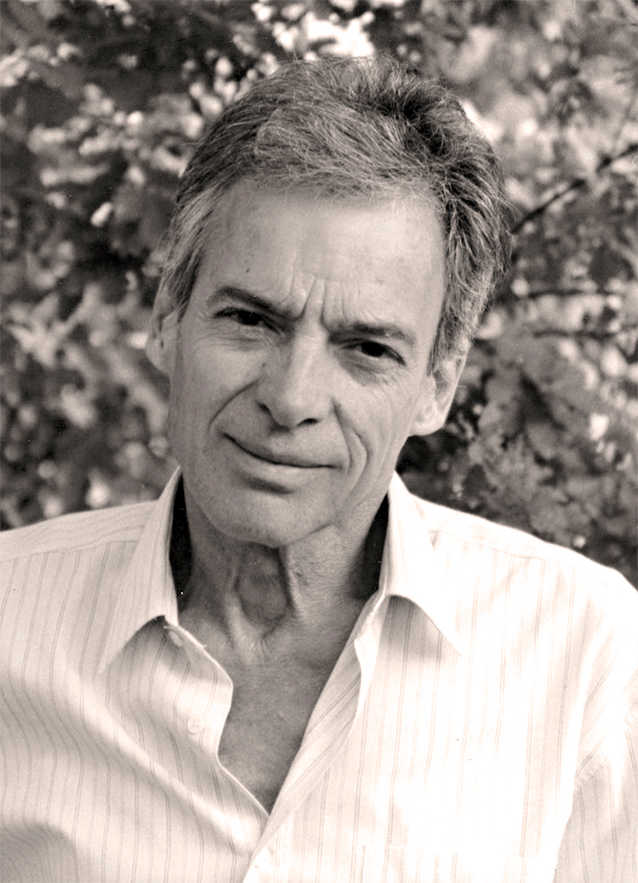

Alain Daniélou and India: A Path of Integration and Freedom

Adrián Navigante: Alain Daniélou Foundation Research and Intellectual Dialogue

In his essay Das Seelenproblem des modernen Menschen (Engl. The Spiritual Problem of Modern Man), C. G. Jung points to a paradoxical and epoch-making coincidence in the history of European civilization: at the time of the Enlightenment and the enthronement of the Déesse Raison, a French orientalist, Abraham Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron, translated a collection of fifteen Upanishads, enabling the Western world to approach the enigmatic spirit of India (1). The coincidence is paradoxical because Duperron, like the encyclopaedists and revolutionaries of 1789, was French, yet what he brought to life immediately showed the one-sided rationality of the Enlightenment and disclosed another concept of knowledge (vidyā) at the antipodes of that of modern science (epistêmê) (2). The coincidence is also epoch-making because the door opened by Duperron proved to be a similar but fully antithetical change of paradigm for the Western spirit, just as the French revolution had been regarding the social structure and civil life of the ancient régime. Nothing would be the same in the West after the discovery of Indian metaphysics and spirituality, and the idea of a new Gnosis through the integration of East and West would seize many brilliant spirits (Rudolf Otto, Mircea Eliade, Ananda Coomaraswamy, et al). All this is actually very well known. What still escapes many people is the fact that Duperron didn’t translate his selection of Upanishads from Sanskrit, but from Persian, and that he didn’t translate it into French, but into Latin.

India’s symbolic irruption into Western culture was characterized by the constitutive effacement of both source and target languages. This should be borne in mind not exactly as a deficiency, but rather as the disclosure of a creative, flexible and varied structure of identity formation. The absence of any well-defined and fixed parameters as to what was being received and to what purpose it was transmitted facilitated the proliferation of inventions and reinventions of Indian culture, not only Arthur Schopenhauer’s fusion of Brahmanism and Buddhism (from Duperron’s Latin translation) in his doctrine of the negation of the will, or Hesse’s literary universalisation of Siddharta Gautama (from Eugen Neumann’s German translation of the Pali Canon) in his unforgettable Siddharta, but also Madame Blavatsky’s uses and abuses of Hindu mythology, cosmology and metaphysics in her Secret Doctrine (out of numerous although scattered glimpses into Gnostic, Alchemical and Rosicrucian doctrines), René Guénon’s invention of an eternal Brahmanism (out of the modern Gnosis of French esotericism) and Aldous Huxley’s flirtation with a sober version of Hindu mysticism (out of his experiments with Mescaline and his regular exchanges with the iconoclastic Jiddu Krishnamurti). Some have viewed this proliferation as a deviation from a “norm” (usually identified with the pole of the source language and therefore with the original culture). The problem is to provide the norm so that discourse about it may reach a point of solid conviction as to the importance and the delimitation of the contents transmitted. As early as the XIX century, partly as an attempt to systematize and correct the profound but incorrectly elaborated intuitions of philosophers like the brothers Schlegel and Schopenhauer, German philology sought to provide a scientific norm, which would also serve to distance alienated esotericists from any valid possession of Indo-European religiosity. The recovered source was the Sanskrit language, and the established target was the jargon of the scientific community (as opposed to the existing normal examples of fragmentary translations and elucidations, whether English, French or German). However, even this scientific utopia couldn’t do without an imaginary basis. Friedrich Max Müller, one of the giants of Vedic studies, died without knowing India and (even more surprisingly) without regretting it: he had spared his idea of Indian civilization any confrontation with the reality of the subcontinent (3). But physical distance was not the only problem: even for orientalists who, at the time of the French Revolution, already knew India, like the first great Sanskrit scholar Henry Colebrook, the culture of the subcontinent was only represented by the type of the Brahmanic mainstream that fitted in with the expectations of colonialists. There is no doubt that such selectivity goes hand in hand with an image of “the other” as complementary, compatible, likened and therefore fully subordinated to “one-self”. The scientific construction of India was mainly the result of an idealized basis of highly selective textual evidence, amplified and projected onto the totality of that culture.

In this fascinating history of imaginary appropriation of India, the generation at the beginning of the XX century marked a turning point owing to the specific tenor of its approach. I would like to call it the European diaspora of the 1930s (all residing in the mythical city of Benares). The English poet Lewis Thompson, the Swiss painter and sculptor Alice Boner and the Austrian art historian Stella Kramrisch are some of the figures of this generation who knew India at first hand, adopted it as a homeland and identified themselves very strongly with the cultural and spiritual inheritance of the Indian subcontinent. Among these figures there is, of course, Alain Daniélou, whose profile could not be so easily drawn as in the case of the previous figures. Was Daniélou a musician, a dancer, a painter, an indologist, a musicologist, a philosopher, or a writer? Or perhaps all of them at the same time? Can he be called “French”, although he denied this epithet, having grown up in pagan Brittany (wholly allergic to Catholic France) and having learned almost everything he deemed meaningful in the traditional Hindu context of Benares rather than at European universities? Alain Daniélou left Europe when he was very young seeking a kind of freedom that he could not find in his immediate cultural context: freedom of thought and action, a way of productively and creatively channelling his unquenchable thirst for knowledge and understanding far beyond the small parcel of purely subjective experience and locally inherited identity. However, when he returned to Europe after his long sojourn, he brought an Indian message to the West and, at the same time, he re-discovered India in the most ancient layers of Europe. He was therefore a very special kind of Frenchman, because he could join two poles that, according to Jean Biès, represent the antithetic relationship between France and India: humanism on the one hand, and divinism on the other (4).

The members of the European diaspora in Benares opened another horizon on the incorporation of India into Western culture. Their relationship with India was not the result of a purely subjective fascination or a relentless will to conquer, but rather the consequence of a very strong identification manifesting itself in an interesting combination of disciplined study, mimetic assimilation and creative reconstruction and expansion. Alain Daniélou, as an example, wanted to embrace the very layer of Indian civilization that proved to be farthest from the (colonialist) Europe he knew; this was why he undertook a thorough education of sensibility and intelligence in order to re-create himself: he learned to speak Hindi to the point of doing away with the mediation of English, he learned Sanskrit as a living language out of the oral transmission instead of through philological text interpretation, he studied traditional Indian music with one of the most reputed Vina masters of that time, Shivendranath Basu, and was initiated into Shaivism by a traditional local pundit and sannaysin, Swami Hariharananda Saraswati (better known as Swami Karpatri). He also worked at the Banaras Hindu University collecting, studying and classifying music documents in Sanskrit from all over India (5). For that purpose, he was granted the status of professor, but he always remained very sceptical towards men of learning, especially Westerners, who were “accustomed to interpreting the vestiges of a ‘dead’ civilization” (6). Indian culture, Indian philosophy and religion were for him not only objects of research, but above all living realities with a dynamic and complex transmission process that he had experienced first-hand.

For Daniélou the Indian system was not reduced to yoga and spirituality (which is what has always attracted Westerners), but included every aspect of life, especially social organization and cohesion – hence his very severe opinion on modern reforms: “When the government [after Indian Independence] began to promote changes in Indian society, its main goal was more often to appear modern in the eyes of foreigners than to improve the lives of the Indian people” (7). Despite its undeniable problems, Indian society is, in the eyes of Daniélou, very inspiring because of its ability to structure a dynamic multiplicity of ethno-social-religious-cultural groups and provide them with permanent protection. This also explains the importance of Tradition, as an uninterrupted chain of (sacred) values handed down through specific selectivity criteria and influencing not only the order of society but also of the whole cosmos. Having left the European milieu when he was still young, Daniélou’s identification with the “incommensurable other” of European culture was not motivated by the type of (vague) spiritual attraction towards the figure of a guru (which very often proves to be a compulsive reaction to cover the psychological setbacks of Western development), but rather a profound interest in the huge diversity of the culture and its perspectivistic coherence. His approach was transversal (although he used the metaphor of linear transmission), heretical (although he always proclaimed his commitment to Hindu orthodoxy) and singularly intercultural (although he usually declared himself an outsider with regard to Western culture) (8). He aimed to show the richness of Indian culture to the Western world by approaching various complex subjects with remarkable intuition and deep awareness of the propaedeutic nature of his contributions. Books like Yoga, Method of Re-Integration (1949), The Four Senses of Life in the Tradition of Ancient India (French version 1963, English version 1993), Hindu Polytheism (French version 1960, English version 1964), The Ragas of Northern Indian Music (1968), A Brief History of India (French version 1971, English version 2003) and his unabridged translation of Vatsyayana’s magnum opus: The Complete Kāmasūtra (1994), bear witness to his monumental effort towards the culture he adopted as his own.

Perhaps the most interesting and creative aspect of Daniélou’s approach to India is his interpretation of Shaivism as a religion of Life, that is, a religion that deifies the immanence of nature instead of postulating a transcendent principle, a religion of eros instead of a doctrine of asceticism that rejects emotions, affections and the tension of contraries, and especially a religion in which every being (not only humans) has a place of dignity in creation and should therefore be respected as such. The deification of nature and eroticism shows an aspect of Hinduism that is far from the Vedantic metaphysics imported through Duperron’s heritage, elaborated by Schopenhauer, adopted (with a vague mixture of Gnosticism) by most XX century esotericists, tolerated and even supported by Christianity and popularized by modern Indian gurus, most of whom come to Europe and the United States to make money. In fact, Daniélou traces a contrast between the Aryan civilization, the heritage of which is textually codified in the Vedic canon and ritually exercised by Brahmanism, and the pre-Aryan culture of the Indus valley, out of which two religious attitudes took shape: the phallus cult and the cult of the mother-goddess (9) (nowadays incarnated in autochthonous forms of Shaivism and Shaktism). Both attitudes express a polarity that structures the movement of the cosmos and generates a tangle of oriented movements that come into existence as the multiplicity of the created in a play of interacting forces. Phallus and vulva are no mere anatomical forms, but reveal primordial forces of which human beings can become aware and to which they can reconnect in the exercise of their own potentialities – most of all in sensual delight (10). For this reason, Daniélou translates the Sanskrit term ānanda (which in the Vedantic Tradition is known as “bliss”) as “voluptuousness” and affirms that sexual ecstasy (and not its repression) is what brings us closer to the divine (11). This perspective of self-realization, which materializes the spirit and spiritualizes matter, lead also to other forms of integration even beyond the scope of human action, for example the integration of the whole realm of the non-human in the order of creation. The dignity of creation does not depend on human categories of good and bad, pure and impure, beauty and cruelty, but rather on the proportionate distribution of created beings and the mysterious dynamics of cosmic patterns and processes. Animal instinct is in this sense something to be dignified and admired as much as the movement of the planets, the scent of a plant or the inventions of the human brain. “The entirety of Creation in its beauty, cruelty and harmony, is the expression of Divine thought and is the materialization, or body of God” (12).

Had Alain Daniélou remained his whole life in India, his work and heritage would not be so interesting as they actually are, especially for the challenges of the XXI century. His return to Europe, his rediscovery of India in Europe, or more precisely: his attempt to synthesize Indian and ancient European religion, is the last and most creative step along his path of integration. It shows that his living experience of Shaivism was a step towards a recovery of what in his eyes had been a universal religion of nature and life, an art of living that he associated with the Dionysian cults and other similar trends in pagan antiquity. Daniélou’s active engagement to recapture the animistic substratum of religion and lead human beings back to their own source should not be mistaken for a regressive tendency toward some exotic form of primitive cult. It is a conscious process led partly by an unprejudiced intellectual effort to understand the universe beyond the limitations of modern rationality, partly by artistic imagination expressing itself in many forms such as music, painting, dance, and literature. Daniélou’s legacy to posterity consists not only of divers essays on Hinduism and epoch-making translations from the Sanskrit (like Vatsyayana’s Kāmasūtra), Hindi (Swami Karpatri’s The Inner Significance of Linga Workship, The Mystery of the All-Powerful Goddess and The Ego and the Self) and Tamil (the great epics of Ilango Adigal’s Shilappatikaram and Chithalai Chathanar’s Manimekalai), but also in a collection of water-colours, photographs, musical compositions (including a musical adaptation of Rabindranath Tagore’s poems), short stories, plays and his well-known autobiography, The Way to the Labyrinth. The title of his autobiography summarises his whole life journey by means of an ancestral symbol, the Labyrinth, expressing (as Daniélou himself says) a spirally-coiled path along which one does not “lose” but rather “finds” oneself. Finding oneself is the result not only of integrating several elements of different cultures as personal (and collectively functional) myths to fill one’s own life with meaning, but also the result of freeing oneself as far as possible from the inherited constraints of dogmas, prejudices, aversions, envies and inferiority complexes that separate us from the rest of creation and make it impossible to embrace its fullness.

Notes:

(1) C. G. Jung, Das Seelenproblem des modernen Menschen, in: GW 10: Zivilisation im Übergang. § 175.

(2) The term vidyā expresses a form of insightful (cf. Latin videre) knowledge through which subject and object are coalesced and self-realization is achieved, whereas the modern idea of episteme means full detachment from subjective experience and experimental observation leading to a description of the analyzed phenomenon.

(3) Cf. Hans-Joachim Klimkeit, Friedrich Max Müller, in: Axel Michaels (ed.), Klassiker der Religionswissenschaft: von Friedrich Schleiermacher bis Mircea Eliade, pp. 29-40, especially p. 32.

(4) Jean Biès, Littérature française et pensée hindoue, des origines à 1950, Paris 1974, p. 18.

(5) Cf. Alain Daniélou, The Way to the Labyrinth, New York 1987, p. 149, also Nicola Biondi, A Descriptive Catalogue of Sanskrit Manuscripts in the Alain Daniélou’s Collection at the Giorgio Cini Foundation, Udine 2017, S. 10-11.

(6) Cf. Alain Daniélou, The Way to the Labyrinth, New York 1987, p. 248.

(7) Cf. Alain Daniélou, Ibidem., p. 217.

(8) “For someone who had experienced almost nothing of the war, the occupation, or the genocides, Europe made a very strange impression […]. It was very difficult for me to understand the problems, states of mind, and attitudes of the people around me […]. I felt […] like a complete stranger in the land of my birth” (Alain Daniélou, Ibidem., pp. 220-221).

(9) Alain Daniélou, The Hindu Temple. Deification of Eroticism, Rochester: Vermont 2001, p. 7.

(10) Alain Daniélou, Ibidem., p. 8.

(11) “The orgasm is divine sensation […]. The ecstasy of pleasure can reveal divine reality to man, leading him to detachment and spiritual realization” (Alain Daniélou, The Phallus. Sacred Symbol of Male Creative Power, Rochester: Vermont 1995, p. 18).

(12) Alain Daniélou, Gods of Love and Ecstasy. The Traditions of Shiva and Dionysus, Rochester: Vermont 1992, p. 13.

Phenomenology of Religion as Religion of Life: A Programmatic Introduction

Rolf Kühn: Professor of Philosophy at the University of Freiburg im Breisgau

The aim of the Religion of Life project is to surpass the scholarly milieu in which it was born. Indeed, in the development of Rolf Kühn’s thought, particularly his openness to experiment beyond the Christian religion, many points of contact can be found with Alain Daniélou’s religion of nature, despite the fact that the latter insisted on the need to recover the animistic substratum of all religion, differing from Rolf Kühn’s conception of the source. In particular, their points of contact regard the consequences of the practical philosophy of life propounded by both authors. Beyond the usual differences concerning intellectual, cultural and experiential background, both authors seem closer in the exercise of a fundamental attitude toward life itself and its essential questions: existence, time, life, death.

With more than thirty books and about a hundred articles published on the subject, Rolf Kühn is involved in collaboration between the Alain Daniélou Foundation and the University of Freiburg. He also translated Alain Daniélou’s Shiva and Dionysos into German last year.

Rolf Kühn’s essay has been translated and adapted for the Cahiers de la Fondation by Adrián Navigante.

A radical phenomenology of life is a philosophical position focused on a primordial plane with a fully “practical effectuation” of life itself, that is, life in its absolute modality, independent of its empirical realization on the plane of separated beings. Usually, people speak about “life” referring to the life of an individual, the life of a finite and mortal being. That is not the primordial plane I refer to. Absolute Life is primordiality; it affects itself before it affects anything else, and its self-affection is the root of all religiosity (even before the creation of the world). The usual designation for this modality of the absolute is God, and it is quite adequate, because God is essentially a purely living being even before saying that he is a creator.

Consequently, the different manifestations of religion can be regarded as modalities of the primordial revelation of Life: an inner or a-cosmic revelation, which does not take place at a specific point of time, but permanently – or more precisely: eternally (for “eternity” lies outside the coordinates of space and time). There is nothing metaphysical or esoteric in this. If Life affects itself before affecting whatever world instance that presupposes an “outside”, a “pro-jection” or an “alienation” of Life itself, this “before” falls out of the temporal framework used to designate the manifestations of the world of objects and even the perceptions of the individual subject. Life is movement and energy that precede everything revolving around the world we see and the personal experience we are accustomed to. This is, in religious vocabulary, the “living word” of God, the self-donation of absolute Life in its utmost instance of self-revelation.

Seen from this perspective, we can say that it is not only external testimonies that speak about the bond between religion and life. In our own time, the possibility of experiencing an immanent bond is given through phenomenology, a discipline that enables us to delve into the primordial sphere where another revelation of Life takes place before any world-objectifying instance. If the primordial manifestation of Life is Life (in its modality of Absoluteness) revealing itself to itself, our life (which immediately takes part in the plenitude of absolute Life) appears as sacred, and we gain a profound conviction of its value, even beyond any kind of social convention. The affective self-apprehension of Life, its originary effectiveness, is the utmost instance of passivity, because it does not create beings separate from their source; it does not place something outside of itself; it does not distinguish itself from living mortal or finite beings on the level of affection, and thus it enables everyone to feel its participation in the primordial source: each being participates in absolute Life. On that level there is no separation whatsoever, but only a single invisible stream permeating the totality of existing beings.

Rolf Kühn, whose work continues and expands Phenomenology of Life in the direction of a Religion of Life in some aspects quite close to Alain Daniélou’s Shaivism.

Rolf Kühn, whose work continues and expands Phenomenology of Life in the direction of a Religion of Life in some aspects quite close to Alain Daniélou’s Shaivism.What is the relationship between absolute Life in its self-revelation and the enigmatic phenomenon called “culture”? Is culture a collective manifestation of Life? From a phenomenological perspective, we could say that culture is the historiality of Life’s self-revelation, its stepping out of its transcendent core. Life does not only manifest itself to itself in a sphere where nobody can make sense of it, or even act as a kind of existential response to the source. There is a trace of absolute Life within the logic of time, memory and representation, which infallibly appears with “culture”. Culture can be viewed as the repository of absolute Life in the sphere of separation and relativity, that is, in the sphere of becoming and multiplicity. But since Life is plenitude, we can view its permanent self-donation as a form of “growth”, as an intensification and expansion in its deepest effectuation mode. Every individual life-form must experientially recognize that level of life-donation, since it is nothing else than experiencing the Absolute in oneself. The manifesting Life-energy on a cultural level (in works of art of all types) is identical to its self-affection viewed phenomenologically. Because of self-affection our lives are bound to a unique Self, out of which individuals are reconnected with Life and become instances of absolute subjectivity. We can say that individuals are (absolute) subjects before they reach the plane of individuality and separation. This source was designated by different names in the past: resurrection, redemption, sacrifice, real basis of all things, etc. Every soteriological path in the various religions considers the possibility of re-connecting with Life as the key to self-realization or salvation.

While it is true that human beings are related to absolute Life, it is also true that Life is not at their disposal, since the originary force of Life is the source of all, rather than an instrument of any kind. Absolute Life transforms the tension of finite beings, their survival instinct, their abandonment to the tonalities of self-suffering and self-joy (summarizing the effect of absolute Life in the world sphere) into a growth beyond the internal limits of a Life-immanence prior to world-experience. The plenitude of Life can only be experienced at the level of receptivity, that is, when individuals open themselves to the “affective flesh” and enter the primordial sphere instead of indulging in all sorts of exercise of extraversion in order to gain acknowledgement and distinction in the world. This entrance into the primordial sphere is called “incarnation” and, on this level, there is no distance whatsoever between the individual self and the source of absolute Life: the transcendent basis of manifestation is not ecstatic (that is, a projection towards the outside forcing a separation from the source). Each life is, because of its own nature, a religious life; every individual is in its very core an absolute subjectivity. The passage of the Absolute from eternity to history is effected through the incarnation of life in the individuated forms of its self-donation. Life is the living work of the Absolute, which reveals itself in the phenomenological matter of the living individual (flesh, living body, affections, emotions, etc.). But, as stated above, the individual is not alone. He is driven by a force that permeates all other beings, and he is therefore united with other beings by means of the coming-to-existence of this force.

In this sense, Life is not just a concept, but absolute phenomenological Reality. It cannot be deduced in a Kantian sense, as an a priori category, since the sacred and the religious are not subject to any deductive process. The Absolute is no abstract principle: it is only principle in the sense of “donation source”, and religion is the theory and practice of this living and concrete principle permeating every instance of being in the world. Such statements would not make sense however if Life did not possess the originary self-affection effecting an “object” out of its own receptivity, that is, producing living individuals that, from an ontological point of view, are not emplaced and thus separated from it. Each thing is “donated” in this way, as part of the phenomenological effectuation of absolute Life, and the modality of donation in the permanent movement of Life can be seen as the living “logos” of every religion that adheres to this principle. The “logos” is immanent to absolute Life. It is the living word of the inner revelation (or self-revelation) of Life, and as such it founds the radical phenomenology of religion, which we also call “religion of Life”. With regard to this “logos”, we understand that the immanent structure of our transcendental affectivity is rooted in absolute Life (which is also called “God”). From a phenomenological point of view, we can formulate the following proposition: that which God experiences is something I can experience deep inside, but this depth is not an abstract spirit fully separated from matter; on the contrary, it is the affective or fleshly layer of myself. The substance in which the Absolute effectuates itself (as originary Life) is pathos, that is the pure passibility of every affective self-impression. This pathos constitutes an immanent certainty related to the feeling of “being alive” and “individuated every second” – whereby “being individuated” is not being separated from all other beings. Jubilation and affliction, joy and suffering are thus reciprocal phenomenological conditions interwoven with each other, so that a permanent transmutation from suffering to joy without any loss of the inherent affective substance takes place within the field of subjectivity on the level of the individuated “self” and in essential relation to the historialized Absolute. For the phenomenology of Life, finitude implies the infinite, because there is no separation between them on the level of the transcendent birth of the individuated self (which is not the ego!) in the Absolute. Religion appears in this sense as the practical form of knowledge on the Reality of Life, and its validity is apodictic.

What religion transmits on the level of representational belief is a certain knowledge about the ontological passibility or the metaphysics of everything that exists as well as a deep faith in an ultimate atonement. What is expressed in religious terms regarding the existential attitude of human beings is, from the point of view of radical phenomenology, the essential characteristics of Life in its absolute materiality, an archi-intelligibility (or primordial gnosis) which is at the same time donation and reception. This intelligibility has nothing to do with reflection on the level of consciousness. It belongs to the immediate movement of Life before its realization on the human level of (mental) re-presentation. Life is ontologically intelligent because it creates two related dispositions on the level of individuation: passible finitude and the experience of atonement. Both are part of the Absolute and both are the main dispositions of every religious faith. Knowledge of Life (as subjective genitive) is a practical form of knowledge proven by the experienced interiority in everyone. In this interiority, the main evidence is the feeling of (our) Life. Contingence does not only reveal the absence of a foundation due to the limits of existential meaning or to the presence of death as a cruel exteriority within one’s own biographical events. It rather points to its transcendental generativeness, to the self-affective effectuation of the Absolute in the sphere of individuated phenomena. Seen from this perspective, atonement is no eschatological expectation of something to be accomplished, but a unity that has already been reached: the unity of joy and suffering, sealed by absolute Life without any rapport to ecstatic temporality (past, present, future). Worldly transcendence knows no conjoined joy and suffering as the subjective materiality of Life or, more precisely, of the self-revelation of Life in us. This means that neither suffering nor joy in their primordial realization are part of the world. They are, viewed phenomenologically, an archi-fact. They belong to the primordial sphere of absolute subjectivity before they step out into the world as subjective-objective instances.

Although all religions speak of God as creator (that is, the origin and acme) of life, the proposition affirming the existence of God cannot become a certainty unless it refers to fleshly or passible self-affection. God as the object of an onto-theological argument is a figure that makes no sense, since it remains forever on the horizon of transcendence related to intentional understanding. The God of onto-theology is a God placed outside the field of immediate experience, since the only thing that can be intuited in such a case is distance (God as infinite, that is unreachable transcendence), not presence. But Phenomenology of Life shows us that Life recognises no distance regarding itself, meaning that God as the living being par excellence cannot be apprehended except through our interiority (which corresponds to the immanent manifestation of Life). The revelation of Life in itself implies, at the same time, a revelation of what is called “God” outside of world language, that is, a total donation of primordial energy, a self-donation of Life. It is impossible to grasp this revelation in terms of cognitive or sensible spheres (always related to the formation of an object: object of perception, object of knowledge, etc.), since it is a totality given to itself and received by human beings on the level of a transcendental (or vertical) birth of the subject without any distance from the source. This is called the parousia of origins, the unlimited manifestation of passible Life affecting the depths of individuated beings, prior to any instantiation of relativity, separation or finitude. From the point of view of the individual in the world, this Life is perceptible in the innermost recesses of subjectivity, beyond all possible action or movement of the will, where passivity becomes unlimited openness to receive the permanent flux of the source without any existential, temporal or worldly hiatus. We are only impotent in the face of Life when we cannot maintain this total passivity (atypical in human beings) in order to receive uninterruptedly the fullness of the source.

Vedānta and Holistic Health

Basant Gupta: President of the Alain Daniélou Foundation ’s Board of Directors

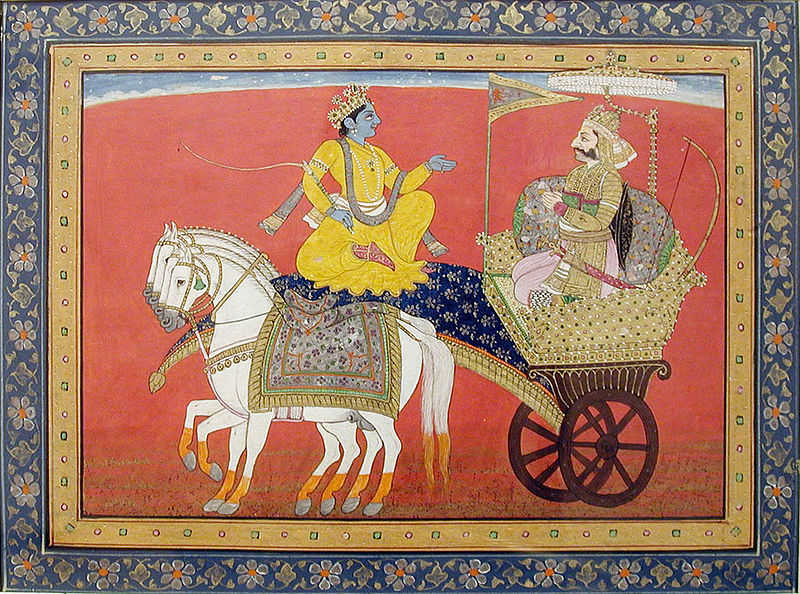

The Sanskrit term for health is svastha which has two roots: sva means “self” or “soul” and sthā means “to stand firmly”. Thus, a healthy person is one who dwells in the Self. Ancient wisdom states that in order to have a healthy body, one’s mind needs to develop soul-consciousness and move away from body consciousness. The concept of soul as an eternal and indestructible entity is beautifully described in Chapter 2 of the Bhagavad Gītā:

Weapons cannot cut it, fire cannot burn it, water cannot make it wet, and the wind cannot make it dry. (BG 2.23)

The verse emphasizes the fact that ātman is eternal, indestructible, all-pervading, changeless, immovable, and primeval.

Legend has it that when Alexander the Great came to India he met a yogi sitting underneath a tree in deep meditation. Alexander asked the yogi to accompany him to Greece saying, “I will give you everything you ask for. My people would love to meet you!” The yogi quietly answered, “I need nothing, and I am happy where I am!” This was the first time that anyone had turned down Alexander’s request. Unable to control his rage, he thundered, “I am the Great King Alexander. If you will not listen to me, I shall cut you into pieces!” Unperturbed, the yogi answered. “You cannot kill me! You can only kill my body, as I am the soul which dwells within the body!” Alexander realized his mistake and beat a hasty retreat unable to subdue an unarmed mystic.

Power of Yoga

Having attained knowledge of the soul, the question naturally arises: how does one attain soul-realization? Indian scriptures tell us that this can be achieved by the regular practice of yoga. According to the Gītā, yoga has four definitions. The first one says that yoga is “equanimity of mind” — samatvam yoga ucyate. According to the second, yoga is “excellence in action” – “yogaḥ karmasu kaushalam.” The third definition states that yoga is the union of ātman with paramātman. Finally, the fourth definition says that yoga severs a seeker’s union with sorrow. In other words, yoga practice uplifts the seeker to a higher state of joy and happiness. There is a beautiful verse in the Gītā which describes this aptly:

Let it be known that the severance of union with sorrow is known by the name of yoga. This yoga should be practiced resolutely with perseverance, without any mental reservation or doubts. (BG 6: 23)

In the joyous state of yoga, one is situated in boundless spiritual happiness, and enjoys oneself through transcendental senses. Once in such a position, one is never perturbed, even in the midst of the greatest difficulty. This indeed is true freedom from all the miseries arising from material contact.

Chaitanya Mahāprabhu describes this aptly: “God is like the brilliant light, and māyā is like total darkness. Just as darkness does not have the power to subdue light, similarly māyā can never overcome God”. The Gītā reveals that the nature of God is divine bliss, while the consequence of Maya is misery. Thus, one who attains the divine bliss of God can never be overcome again by the misery of māyā.

Life of moderation

The Gītā further recommends that a life of moderation, discipline and self-control has to be pursued to attain holistic health. The following verse aptly describes this truth:

He who is temperate in his habits of eating, sleeping, working, and recreation can mitigate all material pains by practicing the Yoga. (BG 6: 17)

Sri Kṛṣṇa declares that those who are moderate, restrained and regulated are eligible to practice yoga, which is the union of the soul with God. The opposite of Yoga is bhoga, which means engagement in sensual pleasures. Pursuit of bhoga eventually results in roga (disease). The same instruction was repeated by Gautama Buddha, when he recommended the golden middle path between severe asceticism and sensual indulgence.

Healthy Diet

The Gītā emphasizes the need for a healthy and balanced diet for the well-being of the individual. Three verses relate to Ayurveda—“the science of long life”. These verses tell us about the influence of the kind of foods we eat on our overall physical and mental health as well as our happiness.

Persons of sattvic nature prefer foods that promote long life, vitality, strength, good health, happiness and contentment; foods which are juicy, succulent, nourishing and pleasing to the heart. (BG 17: 8)

For a healthy mind, it is essential to have a healthy body. It is important for a seeker to consume the right kind of foods to have inner and outer vitality. These foods are described in this verse with the words “āyuh sattva (…) vivardhana”, meaning “which promote longevity”. They provide good health, strength, joy, and satisfaction. Such foods are juicy, smooth in texture, tasteful, and beneficial. These include milk, yogurt, cereals, pulses, fruits and vegetables, and other vegetarian foods.

Hence, a vegetarian diet is considered conducive to the spiritual life. This view has been shared by a number of well-known philosophers in history, including Albert Einstein who wrote:

“Nothing will benefit human health and increase chances for survival of life on Earth as much as the evolution to a vegetarian diet.”

Foods that are very bitter, sour, salty, hot, pungent, dry and spicy are dear to those in the rajasic mode. Such foods cause grief, misery and disease. (BG17: 9)

Rajasic foods are highly bitter, sour, spicy, hot, pungent, acidic, etc. Such foods cause pain, indigestion, ill health and disease. Persons in the mode of passion find such foods palatable, but those in the mode of goodness avoid them.

Foods that are stale, tasteless, putrid, rotten and impure are dear to those in the mode of ignorance. (BG 17: 10)

Cooked foods that have remained for more than one yam (three hours) are classified as tamasic. Foods that are impure, have bad taste, or possess foul smells come in the same category. Impure foods also include all kinds of meat products. Foods that are stale, insipid, tasteless, and intoxicating such as meat, fish, eggs, wine, alcohol, tobacco, opium, etc. are the foods of choice for those situated in tamas gūṇa (the quality of darkness).

Power of Truth

The Gītā further tells us that what we speak is vitally important for our well-being and holistic health. The following verse is very significant:

Speech that is truthful, pleasing, inoffensive, and beneficial, and which does not cause distress; and regular recitation of the Vedic scriptures- these are declared as austerity of speech. (BG 17:15)

The ancient text Manu Smṛti says: “Speak the truth in such a way that it is pleasing to others. Do not speak the truth in a manner harmful to others. Never speak untruth, though it may be pleasant. This is the eternal path of morality and dharma.”

Purity of Thoughts

Apart from the importance of spoken words for our well–being, the purity of our thoughts is also linked to our holistic health. In fact, the Gītā says that regular practice of yoga leads to internal purity. The following verse appropriately describes the same:

Serenity of thought, gentleness, silence, self-restraint, and purity of purpose- all these are declared as austerity of the mind. (BG 17: 16)

The austerities of the mind mentioned in this verse are serenity of the mind, goodness to other, external and internal silence, restraining one’s mind to stay focused on self-realization, and purity of purpose. These austerities of mind are in sattva gūṇa, or the mode of goodness.

In Chapter Six, the Gītā says, “Elevate yourself through the power of your mind, and do not degrade yourself; for the mind can be the friend but also the enemy of the Self.” It is a matter of fact that one’s state of mind determines the state of one’s consciousness. Each thought we dwell upon has consequences. Thought by thought, we forge our destiny. It is important to realize that we harm ourselves with every negative thought that we harbour in our mind. At the same time, we uplift ourselves with every positive thought that we dwell upon. So, we must cultivate our mind with rich and noble thoughts, while weeding out the negative and debilitating ones. If we allow resentful, hateful, unforgiving, and critical thoughts to reside in our mind, they will have a debilitating effect on our personality. Love brings love, and hate brings hate. For this reason, switching the mind from negative emotions and making it dwell upon positive sentiments is considered a vital requirement for our holistic health and spiritual well-being.

Towards New Metaphors in the Description of Tonal Relations

Danel Cove: Indologist and Musician

The realization of sound in music is comparable to a moment of creation as eruption out of an infinite source of silence containing already the primal resonance.

The realization of sound in music is comparable to a moment of creation as eruption out of an infinite source of silence containing already the primal resonance.It belongs among Daniélou’s seminal contributions to world cultural dialogue that he so methodically researched and compared the various systems of musical theory, the scales and interval descriptions in the East and West both historically, within their respective isolated development (as far as this even occurred!), as well as cross-culturally.

As a practical and practicing musician, however, it was not sufficient for Daniélou to merely research the origins and development of musical thought and perception across continents- already a substantial task-, neither was it enough to create extensive tables allowing comparison between Eastern and Western systems of theory, interval sizes etc. His desire to find practical applications, to expand his own experience, led him, on the one hand, to devote years to the practical study of Hindustani music and, on the other hand, to find a means to truly combine apparently antithetical cultural-musical constructions and traditions, and ultimately to use this synthesis to move forward culturally. Alone his suggestion for a 53-tone division of the octave places him in a long tradition of theoreticians. The creation, however, of a musical instrument capable of accurately reproducing such divisions made him a visionary, in the most positive of senses.

And yet, there is another contribution of Daniélou that somehow hovers between the deeply practical and the metaphysical. The direct, experiential encounter with pure intervals should be an indispensable part of any musician’s training. And yet the formative effects of such experience on the human psyche, on our being, are no less dispensable, on a non-musical level. Daniélou finds himself in illustrious company with many ancient sources who unceremoniously ascribe powerful effects to music. The acoustic confrontation with pure intervals, as well as musical experience using the pure intervals, and even the use of ones own musical imagination for the internal, inaudible production of such intervals are all steps and methods for expanding one’s experience of music and ultimately of ones own consciousness.

In the first steps away from the purely experiential, purely phenomenological, we require, however, some system of description, of thought, which allows us to accurately portray and convey these experiences. We order and relate objects of experience after-the-fact, we “make sense” of them in reflection, perceive coherence and begin to think about these experiences not only in reference to previous experiences but also within the framework of our – often half-consciously acquired – way of thinking about them.

This is a fundamental process of human cognition and is valid for musical and non-musical experiences alike. But questions should arise in the reflective thinker as to the accuracy of the conceptual construct used in explaining or even merely reflecting upon said experiences. It is not only the mathematical accuracy we should be concerned about, so necessary for the production and comparison of intervals; it is also to the conceptual-metaphorical accuracy that we should devote some time, thought and care.

The human experience as conceptual standard: towards less abstraction in the architecture of communication.

The human experience as conceptual standard: towards less abstraction in the architecture of communication.With a certain air of self-evidence, we would all state as a commonplace that when we take any two tones within a given melody, or even between two abstracted tones (the unison excluded), the tones stand in relation to each other such that one tone is higher or lower than the other. And yet, the realm of tonal relations is entirely non-spatial! These are acoustic phenomena perceived by the ear. Why do we then say that one tone is higher or lower than another? Because we apply a cognitive metaphor from our general physical experience of the world of concrete objects to the world of tone. Even more, we impose a construct of perception, which is not only spatial but also, more specifically, linear, onto the tonal experience.

Why is this not done with an accompanying degree of hesitancy? Firstly, because such conceptual metaphors – spatial, linear and directional – are incredibly common and go easily unnoticed. Secondly, because there are certainly many elements of tonal relation that lend themselves to or even allow such metaphorical treatment. Thirdly, it is simply convenient. This is not to be belittled or underestimated. Indeed it underlies a great part of all didactic endeavours wishing to facilitate the approach to new materials or ideas. Its goal is efficacy: to maximise the effort of delineation and ensure the greatest mass of transfer of information, or ease understanding.

Still, the claim must be made that, when using a system of experiential referentiality fundamentally foreign to the original source of experience, certain aspects of the experience of tone and tonal relations are not communicated, perhaps only underemphasised, and maybe not even properly perceived.

Nonetheless, the metaphor of “distance” cannot be entirely ignored. Tones, their frequencies, can indeed be measured and we can describe musical intervals, their size and relation, through mathematical proportions and through distance along a continuous line of frequencies going from the inaudibly low frequencies (or slow vibrations) to the inaudibly high frequencies (fast vibrations).

But the quality of the interval is not described thereby. It is as if I attempted to describe a person, or better, two people, all their physical features – size, hair colour, clothing etc. – and then assume that something has been said about them as individuals, their character, experiences, and even about their relationship to and with each other, their friendship, their way of speaking and relating to each other. It is precisely this quality that is, however, necessary for the true experience of the tones, necessary for the aesthetic experience, and necessary for the spiritual experience.

Again, I do not wish to dismiss entirely the value and applicability of metaphors of distance, of such quantifiable concepts of “ratio” and “proportion”, and also “scale” and “tonal space”. But I do wish to propose that the search for non-quantifiable or rather, non-quantity-based metaphors, images and concepts could help us not only communicate differently but also actually assist us in approaching a realm of experience more “correctly”.

So, what is available to us? If we leave the realm of direct linear metaphors, i.e. conceptual metaphors referring to distance, but still wish to use physical metaphors to capture the relational aspect of musical intervals, then we have for example both volume and mass/weight to use. How can this be applied? Is it not possible to imagine a system of description of musical intervals where they are ordered not according to a linear, scalar system but according to an emotional-affective “weight”, so that some intervals are heavier, others lighter?

Or could not intervals be described in three-dimensional space such that the relationship between any two tones is represented analogous to the relationship between surfaces and their intersections (lines and vertices)? A musical interval represented by a Platonic solid?

Certainly, withdrawing from the field of quantifiability relegates us, as in other fields of human experience, to a certain subjectivity. And yet, I would claim that even within this subjectivity there remains the possibility of approaching a non-quantifiable objectivity. There is something universal to the experience of musical intervals. This universality can be shown partially through the expression of their mathematical relationship and also only partially through the emotive response of the listener. There is a certain lawfulness to our emotional engagement of music and it is unlikely that the interval of a pure fifth, for example, would incite a reaction of fear or trepidation.

Leaving spatial and physical metaphors entirely, we still have a number of options. Representing single tones with individual colours is nothing new. But what of representing intervals with colour? Opaqueness and translucence expressing the “major” and “minor” experience in for example thirds (or seconds, sixths, etc.)? Is there an objective emotional response of a minor seventh that is similar to our response to, say, magenta?

Worthy of mention here is also the work of the Austrian philosopher and mystic Rudolf Steiner, who created a form of expressive dance that uses specific gestures of the arms and hands to express intervals. Note this is not a mnemonic device like the hand gestures used in some systems of solfege. Rather it attempts to express, if somewhat less accessibly than colour, the internal physical experience of musical intervals.

In this short essay I have not attempted to propose and champion a particular metaphoric construction, but rather to point out limitations of the currently most wide-spread one, to suggest possible routes for future exploration and certainly also to stimulate dialogue. I have neither exhausted the possibilities for other metaphors nor touched on some fundamental questions concerning interval perception (e.g. harmonic vs. melodic, ascending vs. descending etc.).

Resisting or changing patterns and structures of thought requires effort and questioning, perhaps ultimately rejecting, conceptual metaphors. But it is a deep act of consciousness forcing us to return with a certain naked purity to the original experience. I believe it is wholly in the spirit of Daniélou not only to expand our consciousness of the experience of musical intervals, and not only to apply this practically in making music, but also to purify our conception of them in thought and language.

The Flowing Goddess, Gioia Lussana

Adrián Navigante: Alain Daniélou Foundation Research and Intellectual Dialogue

A feminine approach to the Śākta tradition of Kāmākhyā

Gioia Lussana. La Dea che Scorre: La matrice femminile dello yoga tantrico. Bologna 2017.

Presentation of Gioia Lussana’s book at the Libreria Aseq in Rome. Back centre: Prof. Torella comments on a canonical text of Tantric tradition.

Presentation of Gioia Lussana’s book at the Libreria Aseq in Rome. Back centre: Prof. Torella comments on a canonical text of Tantric tradition.It is not my purpose to write a conventional review of this book, whose title in English would be The Flowing Goddess: the Feminine Matrix of Tantric Yoga. The Cahiers de la Fondation do not usually host book reviews, but rather essays opening different perspectives that may contribute to a better understanding of Indian culture in Europe and to a renewed perception of European culture in India. On top of that, Gioia Lussana’s profile is not that of a scholar: she is very close to ritual and yogic practice. She works on comparative mysticism outside the University and thinks that mere textual infatuation does not open the door to the varieties of religious experience that the Tantric tradition in India may offer. However, she studied Indology with one of the best Sanskritists in the Western world: Raffaele Torella (who belongs to a special lineage in the Italian tradition of Oriental Studies leading back to Raniero Gnoli and Giuseppe Tucci) and she conducted fieldwork for quite some time in the Kamrup district of Assam with the aim of investigating the cult of the Goddess Kāmākhyā and accounting not only from a scholarly point of view but also experientially for its yogic and philosophical trend. Within the purview of the Cahiers de la Fondation this is reason enough for commenting on her work, but its interestingly transversal character goes even further and deserves broader attention.

Those aware of the progress of indological research in the field of early Tantrism – especially in its ritualistic core (kula prakriyā) with practices reserved to a clan of initiates and centered on the divine feminine – will find Gioia Lussana’s work a continuation of the kind of research associated with a series of groundbreaking volumes from the Chicago School of Religious Studies, such as David Gordon White’s The Alchemical Body: Siddha Traditions in Medieval India (1996) and Kiss of the Yoginī: Tantric Sex in its South Asian Contexts (2003), Hugh Urban’s Tantra: Sex, Secrecy, Politics and Power in the Study of Religion (2003) and The Power of Tantra: Religion, Sexuality and the Politics of South Asian Studies (2010). In order to understand the singular aspects of this book however, one has to look at certain details rather than abide by generalities. In the first place, the book is written by a woman and dedicated to the Goddess Kāmākhyā (“for You, who impetuously flow in my veins as in all things” reads the devotional dedication at the beginning of the book). From the very start we are confronted with the ambivalence of an author writing with a considerable degree of scholarly objectivity, but simultaneously maintaining a decisively religious outlook. In the second place, she acknowledges the invaluable aid not only of her Western mentor, Raffaele Torella, but also of her two Indian guides – both highly religious persons – on her journey to the world of the Kāmākhyā cult. These details are important and are not only a question of the political importance of gender markers and anti-colonial attitudes, but rather of the implications of a certain constitution and a certain attitude (being a woman and writing as a woman, speaking about the Goddess and speaking to the Goddess), as characteristics transculturally related to a configuration of religious difference and radical alternatives to the mainstream transmission and intelligibility of Hinduism. Why should it not be the same when a woman writes about the Goddess as when a man does it? Analytical Psychology tries to provide a plausible answer to this question: the step from uroboric or symbiotic unity between the mother and child to the separation and rise of individuality entails different perceptions and experiences on the part of the child that vary according to gender distinction: for the male child the Great Mother will always be traumatic and dangerous, and the story of his development will be the story of his struggle against her domination. For a woman, the Great Mother is not viewed as the threatening Other, paralyzing and devouring the child due to their primordial bond. Hence, the originary projection, which is not individual – since at that stage there is still no ego – but archetypal and basically determines the whole development of the person, far beyond mere unconscious behaviour, is a symbolically strengthening participation mystique (1). The results of this process should not be seen as insights into purely individual psychology, but rather as a key to understanding collective behaviour and some of the ideological intricacies of male dominance in the social sphere. Intellectualization is not only the virtue of gaining knowledge in the world of things, but also a (self-defence) mechanism to appease the fear of the Feminine.

So-called Hindu mainstream transmission, which in the minds of some Western esotericists went hand-in-hand with a “Primordial Tradition”, falling incessantly from Heaven from time immemorial and illuminating the heads of some future elite, has proved to be what David Gordon White calls the reformist agenda of Hindu sensibilities (2). It is true that the basis for this reform dates back to the Vedic canon (which does not coincide with the saṃhitā but rather with the Vedantic reconstruction and structuration of the pair śruti/smṛti), and that it is a characteristic of the construction of that canon to appeal to immemoriality and vertical authority (supported by powerful myths of [non-]origins). However, the execution and expansion of that reform is quite modern: only in the XIX century was the semantic field of the expression sanātana dharma extended to claim a religious and political homogenization of the manifold forms of religious experience found in the Indian subcontinent (3). The retrospective look of mainstream transmission on the Indian history of religious ideas and sensibilities left no room for alternative and even transversal forms. Of the Vedic corpus there remained only the speculative part, of the Upaniṣads their reductive soteriology, of the Bhagavad Gītā a decontextualized spiritual universalism and of other Vaiṣṇava forms of devotionalism (for example, the Gaudiya Vaiṣṇava tradition) a sublimated form of love [prema] comparable to the Christian agape. Although this stream of tradition did have a value, its irritating aspect was that its claim to universality was in fact symptomatically selective: a male, ascetic, highly intellectualized, unworldly and even acosmic spirituality.

Tantric scholarship in India and later scholarship on Tantra in the West tried to balance matters by pointing to the value of “amplification” (as the main tendency in the world of Tantras, diametrically opposed to Vedantic reductionism). The possibility of a “religious aesthetics” (developed by Kāśmīri philosophers like Vasugupta, Uptaladeva and the great Abhinavagupta) shed another light on the religious dimension of Hinduism and showed that the way to liberation can be affirmative with regard to emotions, pleasure, passion, frenzy and other instances associated with an intensification (rather than a suppression) of life. Although scholarship talks about transgression regarding Brahmanic standards, the register of this transgression never reaches the degree of concreteness and materiality it announces because the scholarly aim is to amalgamate Tantric practice with theoretical exegesis and to determine the meaning of the former by means of the persuasive power of the latter. This was no problem at the time of mediaeval Tantric philosophers, because Abhinavagupta, for example, had an experiential bond to what he expounded theoretically. Western scholarship on Tantra, regardless of the excellence of some specialists, is in the same situation as a modern Hellenist reading Greek tragedy through Aristotle. Aristotle intellectualized Greek tragedy to the extreme, but he could still “hear” it. Modern philologists resort to solid but ostensible abstractions, incapable of bridging the historical gap that constitutes what Gadamer called “historically effected consciousness [wirkungsgeschichtliches Bewusstsein]” (4). The difference between the Greek and Indian past is that the former cannot escape from the sphere of history as res facta, whereas the latter still comes to life incessantly due to the dynamics of transmission within the framework of Hinduism. Gioia Lussana attempts to reach out and “touch” (5) the Goddess with her research on Kāmākhyā, not only conducting text exegesis and accounting for a “rational” interpretation of the cult, but also by means of conducting Shakta sādhanā, receiving dīkṣā and taking part in the secret rituals of the regional community. At this point, what appears to be “dangerous” by scholarly standards becomes a very interesting tool presenting the subject in quite another light. The objective sphere is always limited, and no scientist would be ready to affirm the “epistemic value” of any non-conventional or altered state of consciousness. Instead, Gioia Lussana picks up the challenge of rendering the subjective sphere (of her own identification with Shakta Yoga and other aspects of the Assam tradition) an intensifier of knowledge and door-opener to further layers of experience without incurring in watered-down versions of yogic practice and philosophy, so widespread in the Western market of new-age spirituality.

This book is very interesting not only for the research Gioia Lussana conducted in Assam (something she shares with other Indologists of various provenances), but mainly for its motivation and ambitious aim of laying the basis for what could be called “a Tantric ontology of the feminine”. Such an ontology is not based on an abstract and unifying principle (even when integrated in an amplificatory aesthetics of self-realization), but rather on the materiality of fluids (especially blood) (6), the ambivalent character of the divine (against widespread identification of the transcendent with the good), the integral cognitive value of bodily experience and the dominance of the chthonic element over a logocentric metaphysics of light and consciousness. This transgressive gesture finds a clear limitation in Lussana’s association of the cult of the Goddess in Kāmākhyā with the non-dual exegetic tradition of Kashmir. Great care is needed with this association. The fact that until the discovery of the Nag Hammadi Library in 1945, Gnostic doctrines had to be learned through the eyes of the Church Fathers does not allow any homologation, but rather a very differentiated hermeneutics enabling us to work out the nuances of the history of effects. From the scholarly point of view (and this is something that Raffaele Torella recalls in his preface), an exegetical reconstruction of historical exegesis is the sole access to such early ritual traditions of the Tantric landscape, since ritual access is denied to non-initiates. Furthermore, it is true that discourse on initiation compels the reader to distrust the self-legitimation of Western members of any “clan” [kula], especially because there is practically no other laconic affirmation of the value of initiation than that made by those with a compulsion to present themselves as something special, which is typical of Westerners (with centuries of individualism behind their backs). However, it is not necessary to orchestrate an initiation scene in order to account for a concrete experience beyond the parameters of textual scholarship. Hinduism is not (only) about texts. It is (also) about ritual practice, demonic possession, sexual ceremonies, bodily exercises, breathing and visualization techniques, configuration of maṇḍalas and yantras, music, dance and even the rituals of everyday life. Those that share all this with Indian people (especially in a tribal milieu) can gain a good idea of what has been – in general terms – uninterruptedly transmitted for millennia. In this sense, the last chapter, entitled Śākta Abhiṣeka (that is, the ritualistic worship of the Goddess, which Lussana translates as “the Tantric initiation of the Goddess”), is of importance, since it describes Lussana’s personal experience, with a description of the first of five sādhanās in the local tradition in which she was immersed. Although the descriptions are limited and there is also a good deal of speculation, the effort is praiseworthy owing to the sincerity of her research. Another person with that experiential background would probably jump to conclusions, especially with regard to his/her own capacities to transmit that line of practice – as usually happens in the West, where almost every practitioner with a certain (imagined or real) talent ends up highlighting his/her vocation as a guru…

Throughout this fascinating book, the reader notices inevitable weak points and contradictions typical of this kind of research. Lussana chooses to formulate very strong theses on the nature and origins of the Śākta cult with which she was involved for some time, borrowing N. N. Bhattacharya’s speculations about the pre-Vedic origins of the cult of the Goddess (which in the form analyzed by Lussana is attested only in the early Middle Ages), its matrilineal social setting, and the relationship between the feminine, nature, fertility and concrete materiality. She points to the transgressive character of the cult of the Goddess (at least in its origins) and mentions Brahmanic efforts to keep it under control, and she even points to the problem of thinking that this female tradition of fluidic immanence and natural powers is within the line of the non-dual metaphysics of Kashmirī philosophers like Abhinavagupta. However, she resorts (especially towards the end of the third chapter) to a scholarly amalgamation of feminine ritualistic religion and speculative (male) metaphysics, subsuming the former in the latter and leaving less structural solidity in the treatment of the kind of transgression she seems to celebrate not only at the beginning, but rather throughout the book. This is not a limitation of the author, but rather a general problem for anyone dealing with a counter-history of Tantric ritual (that is, with a history not based in the first place on canonic transmission and consequently desirous of freedom from Brahmanic domination): the stuff of this counter-history comes mainly from the same source that feeds the official version, so even if distinctions are possible, they will always be disruptive but functional elements reinserted into the mainstream with no great ideological consequences. It is precisely at this point that I see the need for a new philosophical vocabulary in the study of Tantras, coping with the specificity of feminine cults and the history of effects not only within local traditions but also in their perception by the mainstream.

At the book launch at the Libreria Aseq in Rome, I was glad to see that a scholar like Raffaele Torella – who emphasized the danger of “subjective enthusiasm” in projects like Lussana’s and confessed that he did not expect much from revelations based on “personal experience” in the field of Hindu religion – not only agrees with the need for such perspectives, but also supports them actively with prefaces and book presentations, even outside the university milieu. I am also aware that this support also seals an intellectual dependency of the researcher on patriarchal authority, but perhaps the next link in the chain of the Italian paramparā (from Giuseppe Tucci to Raffaele Torella) may be a woman, as was the case with Swāmī Cidvilāsānanda (Malti Shetty) in the Siddha Yoga lineage of Swāmī Nityānanda and Swāmī Muktānanda. Lussana, however, aims to go far beyond the immanence of a specific form of “tradition” (in this case related to scholarship. In reading her book, one has the impression that she is following the traces of women like Sarah Caldwell, whose remarkable book Oh Terrifying Mother (1999) (7) bears witness to a somewhat “transgressive commitment” of the ethnologist as a conditio sine qua non for really understanding certain forms of religious phenomena, and Donna Jordan, whose courageous work entitled Śakti’s Revolution (2012) (8) paves the way for a new figure in the intellectual arena: the female radical free-thinker.

Consideration of the feminine in the field of religious studies demands a meta-reflexion on the relationship between “thinking” and “living” and the intricate modalities of both according to the manifested (or repressed) aspect of the universal “male – female” polarity. This problem has little to do with militant feminism, but rather with the metaphysical enigma of male dominance in the history of human thought and with the refreshing possibility of abolishing intellectual commonplaces of the type “male = thought”- “female = life”, in the hope that a changed configuration of the cognitive field ascribed so far to human experience might be possible and practicable (since the expansion of such experience ultimately knows no gender barriers).

Notes:

(1) Cf. Eric Neumann, Die psychologischen Stadien der weiblichen Entwicklung, in: Eranos Vorträge, Band 4: Zur Psychologie des Weiblichen, pp. 12-54, quote pp. 14-15.

(2) Cf. David Gordon White, Kiss of the Yoginī, Chicago: London 2003, p. 2.

(3) In this respect, it is worth quoting a response from Julius Lipner: “I have yet to discover a Hindu sanātana dharma in the sense of some universally recognised philosophy, teaching or code of practice. Indeed there can be no such thing, for it presupposes that Hinduism is a monolithic tradition in which there is agreement about some static, universal doctrine… [rather than] a pluriform phenomenon in which there are many dynamic centres of religious belief and practice” (Julius Lipner, Hindus: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, London 1994, p. 221.

(4) Hans-Georg Gadamer, Wahrheit und Methode: Grundzüge einer philosophischen Hermeneutik, Tübingen 1999, p. 346.

(5) The book stresses the value of tactile experience as a means of knowledge (for example in analysing the term sparśa in the context of Trika Shaivism), a primary modality that challenges the Western perspective, according to which sense experience has to be shaped by understanding in order to achieve a good noetic result.

(6) The importance of “blood” as a life-regenerating fluid element is not limited to an observation of rituals and speculation on its symbolic value according to certain texts (especially mythical narrations like that of the Devīmāhātmya). It also concerns the etymology of the word Kāmākhyā – which, according to one of the members of the initiatic community frequented by Lussana, contains the morphemes mei meaning “blood” and kha which stands for “power of protection”. This etymology traces the word back to Austro-Asiatic origins and challenges its (quite plausible) Sanskrit analysis, attested in the Kālikā Purāṇa: kāma + ākhyā (“whose epithet is desire”).

(7) Sarah Caldwell, Oh Terrifying Mother: Sexuality, Violence and Worship of the Goddess Kali, New Delhi 1999. Like Lussana’s work, Cadwell’s book is dedicated to the Goddess. The dedication reads: “To She who sprouts in the tender green paddy seedling, who drinks the cup of blood, who shivers through trembling coconut fronds, whose blessing is hard to bear”.

(8) Donna Jordan, Śakti’s Revolution: Origins and Historiography of Indic Fierce Goddesses, New Delhi 2012.

Published by Alain Daniélou Foundation.

| Representative Bureau – Paris: 129, rue Saint-Martin F-75004 Paris France Tel: +33 (0)9 50 48 33 60 Fax: +33 (0)9 55 48 33 60 |

Head Office – Lausanne Place du Tunnel, 18 CH-1005 Lausanne Switzerland |

Residence – Rome: Colle Labirinto, 24 00039 Zagarolo, Rome – Italy Tel: (+39) 06 952 4101 Fax: (+39) 06 952 4310 |

You can also find us here

For contributions, please contact: communication@fondationalaindanielou.org

© 2017 – Alain Daniélou Foundation

EDITORIAL DISCLAIMER

The articles published in this Newsletter do not necessarily represent the views and policies of the Alain Daniélou Foundation

and/or its editorial staff, and any such assertion is rejected.

https://www.facebook.com/FondationAlainDanielou

https://www.facebook.com/FondationAlainDanielou https://vimeo.com/fondationalaindanielou

https://vimeo.com/fondationalaindanielou