Adrián Navigante

THE THREADS OF EROS: ALAIN DANIÉLOU’S ‘IMPURE’ METAPHYSICS

The question of Eros in Alain Daniélou’s thought has often been either rejected or banalized. From the point of view of a disembodied spirituality, it appears as a dangerous deviation from the goals to be pursued if human beings wish to accomplish their highest goal. From a modern and secular point of view, it is the result of a merely hedonistic motivation that does not go beyond the life of any individual. In this essay, Adrián Navigante tries to show quite another dimension of the question: Daniélou’s conception of Eros is closely related to his project of a new humanism and his conviction that there is a form of transcendence implying integration rather than separation, and enhancement rather than denial of life. In this sense, it is the main component of an ars vivendi (art of living) supported by creative and subtly elaborated insights on human beings and their relation to different reality planes of existence.

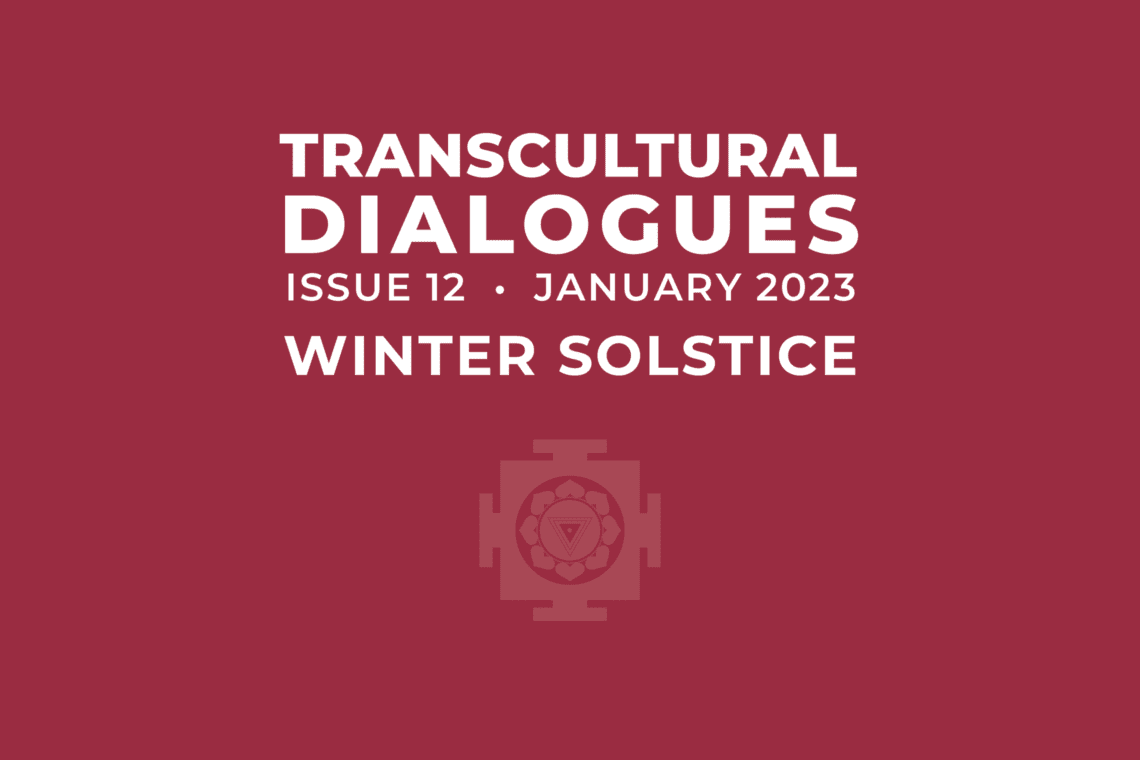

Alain Daniélou at Zagarolo around 1979 working on his erotic paintings. Photo by Jacques Cloarec.

Alain Daniélou at Zagarolo around 1979 working on his erotic paintings. Photo by Jacques Cloarec.Metaphysics: Which ‘Reality’ behind?

If one succeeds in grasping Plato’s effort to accomplish philosophy as an ars vivendi at the time of the Old Academy (IV century BCE), the difference between his conception of the ‘scholar’ [scholáchês] as the head of a human group following a path of self-knowledge and socio-cosmic integration appears as an irretrievably lost ideal compared with the present conception of ‘scholarship’, in which the notions of arts and life, cosmos and wisdom, are irrevocably cast aside on behalf of an increasingly rigid conception of knowledge. Plato’s idea of an ‘academy’ had little to do with the kind of specialized training received at universities today, which in some cases turns out to be more detrimental than beneficial for the expansion of the human spirit. Even where progress has been made over the last centuries in terms of what the collective memory has managed to accumulate through specialized research, there is no doubt that the repercussion of the resulting institutional Ozymandias on the individual’s life-path reveals an ostensible blind spot if the motto ‘development of mankind’ is to be taken seriously. Human sciences have been, for quite some time now, eroded by parameters of objectivity alien to the humanist notion of ‘proper studies’1. That is perhaps the reason why an anti-Platonic author like Georg Lukács declared, in the Nietzschean days of his youth, that the critical essay should not be a scientific piece but a form of art2, or a Marxist like Antonio Gramsci (also on the opposite side of the Platonic spectrum) opposed the dominant view of philosophy as the property of a certain category of specialists by coining the expression ‘spontaneous philosophy of ordinary people’3, or a radical existentialist like Emile Cioran bid philosophy farewell without any hope of replacing it with any other – better or worse – strategy of spiritual consolation, as had been the case with authors like Blaise Pascal and Søren Kierkegaard.

Endogamic closing, exogamic dissolution and existential evacuation can be read as signs of a general crisis. Whenever human intelligence is challenged in such a way, attempts at renovation are a kind of natural reaction, but nothing is clear enough as to which direction should be taken. The problem is that, once philosophy as a discipline of integration is either reduced to abstruse terminology or irreversibly dismissed, intellectual endeavors are likely to be put out of joint or turned upside down – or both. The question whether people need philosophy in order to live is misleading, since philosophy as an ars vivendi is in no way detached from an existential articulation capable of enriching human life: we simply don’t have any choice, at least if we want our lives to be worth living. In other words: ars vivendi does not tolerate an estrangement of thinking from the organic threads of life-experience, nor does it accept the degradation of human nature in automatisms of any kind. It is therefore clear that replacing the alienating straitjacket of specialized discourse by a jargon of dilettantes is no guarantee of a return to a life-changing program for the benefit of mankind. Intellectual history is furnished with creative examples of vulgarization but also full of parasitic appropriations leading to cultural stagnation. The Platonic art of living, injected as it was with a powerful movement of thinking capable of leading humans beyond their own physical and mental determinations, did not seek abstract essences or ultimate principles – as many people think. Its boomerang-like movement permeated every sphere of social life with the extraction of a power coming from outside and located (après coup) as a point of excess among humans. This power was called idea; its excessive character is known as meta-physics.

The word metaphysics is a shining example of a conceptual pandora-box that may serve to illustrate the present crisis and disorientation – that is, the impossibility for most humans to come up with an art of living. There are many kinds of metaphysicians: conscious and unconscious, explicit and implicit, refined and vulgar, scientific and esoteric, arrogant and humble, paradoxical, inverted and perverted ones, wildly experimental and purely conceptual, psychologically or cosmologically biased. If metaphysicians are (despite modernity and secularization) almost everywhere, can metaphysics be located at all? Strictly speaking, the discipline does not have to do with nature [physis], or with the soul [psyché], or with human conduct [éthos], since it has the distinctive quality of transcendence. However, it must be re-linked to each one of those levels if it doesn’t want to end up as a meta-referential caput mortuum. Can it be said to be a theory of what ‘lies beyond’ nature, the soul and human behavior? And if so, should it be taken in the sense of a condition of possibility, a principle or a real substrate underlying the sphere of such experiences? Can it be said to be simply an impulse to ‘go beyond’ the established state of affairs i.e. the taken-for-granted perspective to shape reality? And if so, is such transgression noble or rather disgraceful? Does it feed transpersonal and altruistic purposes or ego-centered and even narcissistic impulses? Is it related to a burning thirst for knowledge or to an unsurpassable fear of death? Perhaps it is both: impulse and reflection. Perhaps it cuts through and along all those motifs, aspects, symptoms, and factors without being capable of choosing the best and isolating the worst of them. Metaphysics, if it aims at concretion, cannot be declared. It is rather something to be composed.

For authors like Mircea Eliade and Alain Daniélou, the Western idea of humanitas needs to be reconsidered as a provincialist construction and therefore re-situated within a broader context, in which non-European cultures play an essential role.

There is a vulgar conception of ‘empirical reality’ contained in the modern trend called positivism, where the concrete, material, three-dimensional and well-delimited aspect of an object is turned into an ontological maxim to build an entire conception of the world. For positivists nature is ultimately a set of dead objects, whereas subjectivity appears as a misleading power to be reeducated toward a more perfected vivisection of reality. In the same way, there is a vulgar notion of metaphysics, in which the spontaneous impulse of exacerbated and uncritical truth-seekers obliterates every effort to come to terms with the intricate texture of human experience. Vulgar metaphysicians will bluntly sever ‘being’ from ‘becoming’, and ‘unity’ from ‘multiplicity’; they will fully adopt the first two and reject the other two altogether. Such an unnuanced way of parting the waters does have consequences on a moral, political and gnoseological level, for example when it comes to drawing a distinction between truth and falsehood, good and evil, identity and difference, or purity and impurity. Life – human, social, cosmic life – implies movement, tension, multiplicity, and change. It does not fit into rigid schemes or homogeneous constructions, nor can it be deprived of contingency and indeterminacy, because both contribute to creating and enhancing relations. Refined metaphysics seeks a criterion of consistency that may hold through the whole spectrum of discontinuities (with its tensions, conflicts, and paradoxes); vulgar metaphysics, on the contrary, tries to impose a transcendent superordinate, forcing the whole world of relations into a reductive grid. Its results don’t do justice to the classical idea of humanitas, the aim of which was to foster the spiritual evolution of mankind. Among other things, humanitas is an ancient pedagogic idea, Platonic in its origins, which was recaptured in the Italian Renaissance by figures like Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola and came to a somewhat unhappy denouement in XIX century Germany with the battle of philologists. The fact that thinkers like Erwin Rohde and Friedrich Nietzsche were cornered into the institutional margins whereas somebody like Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorf moved to the center shows a rather clear picture of the deteriorating process. The situation became much worse in the 1930s, when an idealist like Werner Jaeger wrote his monumental Paideia – still clinging to hopes of renewal that might in a way counteract the impact of National Socialism.

For authors like Mircea Eliade and Alain Daniélou, the Western idea of humanitas needs to be reconsidered as a provincialist construction and therefore re-situated within a broader context, in which non-European cultures play an essential role. The expression ‘new humanism’5 is in this sense an expansion of horizon through a de-centering of referents. The aim of these authors is to transform not merely a way of thinking but a whole spectrum of relations as well as fundamental attitudes and modes of being. Such a process must be necessarily hybrid in character because a change of referents and its corresponding transmutation of values imply operating on different levels and with different elements – sometimes extracted from incommensurable contexts. Mircea Eliade’s hermeneutics of the sacred (in which he challenges both objectivity and temporality), his notion of primitive ontology (where classical metaphysics is purposely combined with ‘primitive thinking’) and his variegated style (he wrote not only academic papers but also essays, novels and diaries) bear witness to the ambition of his project – and the price to be paid for it6. Alain Daniélou, for his part, operates with a notion of Shaivism through which he intends to link not only Brahmanical orthodoxy with Tantric (mainstream and vernacular) elements, but also fragments of pre-Vedic culture with central motifs of late medieval Puranic literature and Tamil folk-religions. This may sound wild and unreflected at first sight, especially if one applies scholarly criteria when reading his work, but for him it was the natural result of an insider’s experience in a Shaiva sampradāya, and since the insider had Western roots, it was necessary to inflect those roots according to the tenor of his South-Asian experience. In other words: Daniélou tried to see ancient European (Mycenean and Greek, Etruscan and Roman) paganism – and subsequently extra Indo-European animist traditions in Africa and South America as well as some aspects of (post-)modern Western counterculture – from a Shiva-centered perspective, that is, through an open-ended maṇḍalic grid of transgressive but at the same time multi-leveled and well-articulated relations reconnecting humans with a much broader and mysterious reality. Such an attempt calls for skepticism and tenacious resistance both from specialists and from dilettantes, since it is too specific for commonplace-lovers and too general for the masters of detail, not to speak of spiritual fundamentalists who postulate a set of fundamental truths in the name of secret knowledge, initiatic chains and spiritual enlightenment – usually under the rubric ‘Tradition’ – to reject all the rest, thus avoiding even a minimal effort to grasp the intricacies of what Daniélou calls ‘the human adventure’.

The Labyrinth of Crete, a significant motif in Alain Daniélou’s later work.

The Labyrinth of Crete, a significant motif in Alain Daniélou’s later work.Sexus as Nexus: Dimensions of Eros

The figure of the labyrinth is not absent in Mircea Eliade’s work7, but it is Alain Daniélou who made it the central motif of his whole work. In Hindu Polytheism (1964), the image of the labyrinth provides the best of Daniélou’s responses to the question of metaphysics as a possibility of human experience: Brahman, the unknowable, lies beyond the limits of perception, “it begins where understanding fails, yet it can be approached from many sides […]. It is only through the multiplicity of approaches that we can draw a sort of outline of what transcendent reality may be”8. The ‘many sides’ can be outlined as traces, and it is by following those traces that human beings compose their lives, embedded as they are in a much broader and never-fully-understood (natural and cosmic) environment. This idea is specified in Shiva and Dionysus (1979), where Daniélou, resorting to a passage of one of the earliest Upaniṣads, declares the following: “The gods don’t like to see humans attaining knowledge […], that is the reason why the path […] is twisted [vakra]”9. Knowledge of the radically transcendent brahman is like reaching the center of the Labyrinth, which is why it is impossible to achieve while we live as individuals on earth, no matter how broad our expansion of perception and knowledge may be. In other words: to reach the unknowable would mean to bring our mysterious pilgrimage of life to an end, to close the very earthly and cosmic window that we are, and with it all possibilities of interaction with the multiplicity of (visible and invisible) beings composing Life. The center of the Labyrinth is not only beyond human reach, but also beyond all other non-human agents we may encounter – whatever the local composition where the encounter takes place. The center of the labyrinth is the reverse-side of Life, the impossible confluence of all traces shaping the manifold – human and non-human – worlds. This does not mean that humans are excluded from all possibility of knowing. Quite the contrary, for Daniélou the articulation of Life is primarily a learning process. It consists in dealing – in a progressively differentiated way – with the many-layered reality of multiple entities and their dynamic interconnectedness. The more aware we participate in it, the closer we come to the divine sphere – which is also a sphere of multiple relations, only with a much more concentrated intensity. Divine life is for Daniélou analogous to the transcendent reality of brahman but with one main difference: it can take place, that is, it is susceptible to being articulated within a sphere of world immanence. It has to do with seizing, yoking, and harnessing a flow of energy stemming from the highest of concentric circles composing the maṇḍala of Life. That is why the figure of the labyrinth is essentially related not only to the esoteric and mysterious, but also to the erotic. Here we reach an essential point. The flowing of erotic energy creates strong bonds, inconceivable relations, and paradoxical correspondences, but above all it brings the whole labyrinth back to a primordial figure of ecstatic dance, as if the very center were to be disclosed inside and outside each dweller who follows the traces10.

For Daniélou the twisted path of knowledge is inscribed in our body. This means that everything we can ascribe to knowledge in terms of meta-physics (symbolic depth, subtle powers, ontological principles, etc.) is impossible to detach from the physical and organic sphere11. In Shiva and Dionysus this connection becomes clear when Daniélou refers to Ganeśa as symbol of the twisted path and at the same time as gate-keeper. In the Gaṇapatyatharvaśīrṣa, Ganeśa is characterized as gaṇānām patiḥ12, that is, “the lord of the multitudes”. In that expression, the word gaṇa refers both to the troops of Shiva [śivasya gaṇāḥ] and to the category of being with a separate existence (since one of its meanings is “number”). Gaṇeśa is therefore the origin or source of multiplicity and at the same time an embodied root-level of Nature’s most primordial powers13. The word vakra (“twisted”) is used when the text refers to the God’s bent or twisted trunk. The elephant trunk, a phallic symbol, stands for the reality of the self [ātman]. Being the limit point between manifestation and non-manifestation, it is considered evasive and ungraspable. At the same time, it appears both as a point of minimal consistency [bindu] and a primordial opening, like a gaping mouth [mukha], an entrance or a passage [dvāra]14. All this is contained in the Sanskrit expression vakramātmamukham15. It is in a related sense that Daniélou refers to Gaṇeśa as the gate-keeper of the root-chakra [mūlādhāra], adding an explicitly sexual reference to the question of the labyrinth: “In the human body, the narrow gate leading to the coiled serpent-goddess is the anus. There we find the center of Gaṇeśa, the keeper of the gate to the mysteries and servant of the goddess. Beyond, we find the labyrinth of the entrails, those tortuous paths leading toward the vital organs which are oracularly interpreted during a sacrifice […] The male organ, penetrating directly to the zone of the coiled energy [kuṇḍalinī], may cause its sudden awakening, thus provoking certain states of illumination as well as the perception of transcendent realities”16. Here Daniélou’s straightforwardness equates that of some Tantras in which there is no symbolic meaning on the textual level but a concrete and un-sublimated one – since the ‘symbols’ are the organs performing the ritual or the substances used in it. What he describes, however, is not simply anal sex but a ritual procedure in which that kind of intercourse is aimed at potentiating, harnessing, and channeling the energy flowing through the three lower chakras: mūlādhāra, svādiṣṭhāna and maṇipūra17. Transcendence is thus reached by a form of embodied meta-physics, in which the body is ultimately an energy tissue with its own – complex – economy of ecstasy. We are of course far from the ecumenical agenda of a disembodied spirituality (like that of universal Neo-Vedanta), for which any reference to bodies, organs and fluids are either metaphors of pneumatic instances or projections of a sick mind. Even if the Tantric economy of ecstasy cannot be equated with a hedonistic pursuit of sexual plenitude18, there is a junction-point between the two, which in a way discloses the nexus between the erotic and the mystical as well as its own inherent detour – the human all-too-human oscillation between perversion and magic.

For Daniélou, the articulation of Life is primarily a learning process. It consists in dealing – in a progressively differentiated way – with the many-layered reality of multiple entities and their dynamic interconnectedness.

All these powers are related to the earth, the primal (fluid, magmatic or chthonic) configuration of which can be reached when the opening to the root-chakra effects the transformation of elements – the passage from mūlādhāra to svādhiṣṭhāna19 – and the revelation of its mysteries20. In Shiva and Dionysus, Daniélou emphasizes the importance of discovering and realizing links between the different levels of being21. Shaivism as a religion of Nature is about broadening the scope of relations and contributing to render them as harmonious as possible, and the first stage lies in the body, its sensations, and the environment22. Empowering the (energy-)body by means of an erotic opening and perceiving the environment as a field of forces instead of a set of dead objects are closely related. This very concrete prescription, which builds the basis of a reeducation program for mankind, has metaphysical assumptions – which will nevertheless challenge in themselves the idea of a disembodied spirituality, so often wielded against Daniélou’s ars vivendi. In Shaivism and the Primordial Tradition, he speaks of the aim of a religion of Nature: “to perceive the divine in its own work and integrate oneself into that sphere”23. This definition is not so simple as it seems. The divine cannot be grasped without the senses, and human integration in its sphere implies an expansion of perception, a transformation of energy level, and mainly the ability to communicate with non-human agency – a trans-human, animistic-related form of intersubjectivity. In other words, the primordial tradition to which Daniélou refers, despite his references to René Guénon, has little to do with the radical metaphysical monism of the latter, in which notions like puruṣa and brahman impose themselves upon the whole spectrum of māyā-śakti and prakṛti. The primordial sphere is for Daniélou the mystery of Nature, and tradition is what human beings can codify out of their individual and collective confrontation with that mystery. From the most powerful nexuses re-connecting human beings with the forces of Nature, Eros has, in the philosophy of Daniélou, the first place, even when he mentions – not without a certain caution – two other possible ways for his contemporaries: entheogen-induced ecstatic experiences and certain techniques of Yoga24. The erotic dimension of human experience is not merely ruled by a biologically driven instinct and its correlative psychological determinants; it adds a differential and transcendent quality to the psycho-physiological pandemonium of sexuality, and it can lead to spiritual fulfillment.

A female member of a Tantric circle being oiled and massaged after a bath and before a ritual. Source: Philip Rawson, Tantra: The Indian Cult of Ecstasy, London 1973.

A female member of a Tantric circle being oiled and massaged after a bath and before a ritual. Source: Philip Rawson, Tantra: The Indian Cult of Ecstasy, London 1973.The Step (not) beyond: On Tears, Fears and Tension

Metaphysics implies a step beyond the empirical sphere through which human beings encounter an instance of (personal or impersonal, form-related of formless) transcendence. The general assumption is that the configuration of reality according to sense perception is an absolute parameter, and that there is a form of experience fully detached from the senses and from everything related to them. The main question to be asked before jumping to conclusions is: what does the term ‘empirical’ refer to? The Greek word empeiría means ‘experience’, so we can say that the empirical sphere is the result of a cultural configuration delimiting what is valid in terms of experiential reality. Observation of different cultures suffices to realize that the value ascribed to ‘experience’ (and therefore the place where the limits of the ‘empirical’ are set as well as the rigidity or plasticity of its threshold zones) varies enormously according to the type of world configuration characterizing the life of the group. The distinction between the empirical and the metaphysical is not the same among modern European Catholics, Indian Brahmins, West-African Vodun practitioners and Indigenous peoples of Amazonia. Even within a culture, there are different attitudes and sensibilities at work which influence the dynamics of such delimitations. Only within Indian culture, the metaphysics of Advaita Vedānta differs considerably from that of Śākta Tantra or Śaiva Siddhānta. The universalization of the former – to the detriment of other approaches – can be seen as a big step toward a vulgarization of metaphysics. Daniélou succinctly mentions this problem in Śaivism and the Primordial Tradition when he says that the hypertrophy of uttara mīmāṃsa (as a result of Shankara’s predominance in modern Hinduism) practically led to the elimination of the other darśanas, and that its triumph in the West progressively clouded the most concrete (and refined) forms of Indian thinking25. Empiricism is far from being an absolute parameter. It is a flexible term – certainly to be questioned if the dominant perspective configurating it happens to be challenged by context and circumstances.

Alain Daniélou’s divinization of Eros can be read as a counter-movement against an increasing vulgarization of metaphysics, against the step beyond that leaves the manifold levels of human experience behind and secludes the spirit in a purely abstract realm26. The consequence of such a metaphysical attitude is a disregard for the world, beginning with one’s own body and continuing with everything related to the material aspects of Nature (as in the advaitic homologation of māyā with ontological inconsistency). Daniélou, on the contrary, locates the origin of erotic attraction in the cosmogonic act of world-disclosure: “When the first tendency toward creation appears in the neutral, inert, and non-polarized substrate beyond movement, space and number, it has already the aspect of a current or tension between two opposite poles. This dual instance is the essence of every physical or mental existence and can be represented as a male and a female principle penetrating every aspect of life”27. It becomes evident that divine reality is not located in the radical transcendent and inert substrate28 but in the original and cosmogonic tension essentially related to the world-shaping power. This is not so much Tantric philosophy as early Upaniṣadic thought. In one of the cosmogonic passages of the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad, it is said that ātman desired a complementary opposite [dvitīyam aicchat], became as a result “a woman and a man closely embraced” [strī-pumāṁsau sampariṣvaktau] and “came together (in sexual union) with his feminine counterpart” [tāṁ samabhavat]29. This sequence does not depict a fall or degradation process from an original principle, but a disclosure of cosmic intensity and plenitude. In the concentric circles of the ‘maṇḍala of Life’, the tension of opposites is kept at its highest intensity through a conflation or coupling [sambhava, maithuna] of male and female energies. That is why Daniélou rejects the advaitic distinction between a self-sufficient or purely spiritual bliss [svābhāvikānanda] and any instance of everyday or object-related happiness [laukikānanda, viṣayānanda]30. Eros is a primordial and transgressive force which embodies the mystery of Life. It leads beyond every instance of differentiated world-experience; however, the differential step leading beyond our limits is not a radical detachment but an intensification and enhanced relation. It is a state of “beatitude and delight, not of silence and death”31.

Shaivism as a religion of Nature is about broadening the scope of relations and contributing to render them as harmonious as possible, and the first stage lies in the body, its sensations, and the environment.

In his book The Tears of Eros, Georges Bataille explores the transgressive force of sexuality and its scope in the life of human beings. Like Daniélou, Bataille emphasizes the essential link between sexuality and the sacred. Unlike Daniélou, he sees a “diabolical aspect” of eroticism, which distinguishes it from mere sexual activity: “diabolical means the coincidence of death with eroticism”32. Erotic rapture, incessantly present in Daniélou’s work, is not in a relation of tendential opposition to, but of paradoxical coincidence with death. Bataille writes in this respect: “Death is associated with tears, whereas sexual desire is sometimes related to laughter. But laughter is not the contrary of tears, as it seems. The object of laughter and the object of tears have to do with some sort of violence”33. The violence he refers to is extreme; it interrupts the ordinary course of things, tearing human beings out of their social framework (dominated by rationality and calculation) and opening the door to an experience of ontological continuity (characterized by a prodigious effervescence of life)34. In Bataille’s thought, continuity means absence of limits, even those of the individual (which is why it has ontological significance). Transgression, experienced in such a radical form, brings human beings in contact with death. This contact is not speculative or metaphorical but rather an ecstatic depersonalization and dissolution. Death is for Bataille no nihil privativum, but the horror of a ṯōhū wā-ḇōhū inscribed in the human flesh itself. Eroticism is therefore related to radical loss35 and transpersonal ravage. If sensuous delight [volupté] appears as the summit of life, it is at the same time delirium and limitless horror36. The main paradox is that, from a phylogenetic perspective, Bataille sees eroticism as essentially related with the fear of death37. In order to escape that fear, rationality offers a civilized life and the illusion of protection and safety, but it cannot placate for long the increasing pulsation of horror. Human beings plunge into the ecstatic excess of Eros in the hope of exorcizing that feeling, and what Eros brings back from that apotropaic trip is ultimately no plenitude, but its own tears, the literal realization of that fear.

Alain Daniélou’s divinization of Eros can be read as a counter-movement against an increasing vulgarization of metaphysics, against the step beyond that leaves the manifold levels of human experience behind and secludes the spirit in a purely abstract realm.

“The two aspects [male and female] of Being are separated”, writes Daniélou in Shaivism and the Primordial Tradition, “so that the spark of sensuous delight [volupté] can appear between them”38. If the rhythm of being in the manifested world of multiplicity consists in a dynamics of creation and destruction – killing and being killed, eating and being eaten39 –, the sexual act fuses the two instances and reintegrates the seemingly perpetual discontinuity. It brings the tension to its summit and restitutes a fullness of being despite the constitutive finitude of the participants. This restitution is the embodied realization of a transcendent reality: “The union of the phallus and the female organ is the symbol of divine reality as well as of the cosmic and physical reality […]. Accomplished like a rite, it is the most effective means of participating in the divine work”40. It should be noted that, in the context of Daniélou’s reflection, the symbol is not something to be intellectually decoded, but something to embody and realize in the accomplishment of a ritual act. This act becomes a passage to another level of being: “[It] is maybe the highest and most direct experience that we may have of the beatitude and the limitless rapture which is the nature of the divine”41. For Daniélou the climax of the sexual union is conveyed in the Sanskrit term ānanda, which – contrary to the one-sided spiritualization of the term in the modern reception of Advaita Vedānta42 – could be rendered as “sensuous delight” or “erotic rapture”. In the Brāhmaṇas and early Upaniṣads, the term appears many times in the sense given by Daniélou43, with the difference that orgasmic thrill (as a mystical moment) is not severed from the procreative act44, as in the case of Daniélou: “Sensuous delight [volupté] […] [is] the experience of an instant of joy during which we forget everything: reason, interest, egoism, duty. […]. Procreation has nothing to do with this sacred aspect of love”45. This emphasis on erotic-spiritual realization lays stress on the power of Eros not only as an experience of transgressive intensity between individuals but also as a fundamental instance of relation surpassing human parameters. The cosmic threads of Eros are in perpetual tension, intensified in union to avoid ontological disaggregation, and simultaneously redistributed to avoid full implosion. The world is thus disclosed – and preserved – as a living tissue of interrelated beings, in which humans are – due to their erotic dimension – capable of having an embodied intuition of transcendence46. In Daniélou’s conception of Eros, there is no diabolical element or malediction of any kind, but a form of pleromatic aisthesis that does not call for tears of any kind. Precisely because the fullness is in this case related to an expanded and intensified form of perception, the transcendence it implies is no radical instance of discontinuity with regard to the world. It impregnates every layer of human experience and revitalizes it. It does not require leaving the body but transforming the objectified and dissected version of it (which is the product of an alienated attitude to oneself and to others) in an energetic body-soul-spirit complex. The world is not disfigured and dissolved, but transfigured and recomposed.

Strongholds of purity, bridge of impurity

Radical metaphysics, which reduces the spectrum of phenomena, contingency and interrelations to a determining instance detached from them, is not only spiritualist. There are also materialist versions of it. In his essay Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Sigmund Freud questions his former model of libidinal economy based on the pleasure principle as regulator of psychic processes. The pleasure principle was thought to regulate tensions emerging in the psyche that might lead to displeasure (discomfort, suffering, pain), either by reducing them or by transforming them into pleasurable sensations. This is not only a problem of energy quantity, but also of the quality of the energy concerning, as Freud says, “the darkest and most inaccessible domain of psychic life”47. The history of subjectivity is one of divisions or fragmentations as a result of the mechanism of repression. The conscious part tries to cope with the enormous task of assimilating tensions, but in such a context pleasure and displeasure are not clearly distinguishable, since the ego itself carries a great deal of unprocessed contents48. For Freud this is not only visible in traumatic neuroses. The observation of non-traumatic self-aggression instances in infantile behavior leads him to the notion of “compulsion to repetition” [Wiederholungszwang]. The puzzling fact of this compulsive mechanism is that the repetition is essentially linked with an experience of displeasure. Do we unconsciously tend to destruction? And if so, in which way is that fundamental tendency compatible with the so-called survival instinct? The living organism, says Freud, is like “a small bubble of irritable substance” which tries to cope with stimuli from outside, but the problem is that the outside has two asymmetric dimensions: the outer world in space and time, in the face of which a conscious mechanism of protection may be quite effective, and the inner world from which the most challenging stimuli arise – a burst of invasive energy that ignores the parameters of space and time. Here lies the conspicuous asymmetry: the dark powers of the inner world, which for Freud are fundamentally connected with sexuality, are too strong and unbound for any conscious assimilation. But what is the purpose of those (destructive) unconscious drives? Freud’s question is neither biological nor psychological, but metaphysical. His suspicion is that the notion of drive is ultimately not related to the preservation of the living organism – although its accomplishment is indirect, that is, it passes through preservation strategies. In other words: if unconscious impulses are by nature ‘regressive’ (in the sense that they always introduce a tension that resists the ‘progress’ of consciousness), this regression does not take place in order to preserve something, but to achieve an earlier state. Since every form of life returns sooner or later to an inorganic state, Freud’s conclusion is that “the purpose of all life is death”49, and he explains this by means of a materialist mythology: “Once upon a time, the properties of life were awakened in inanimate matter by the effect of a power that defies conjecture. Perhaps it was a prototype of what took place later, when consciousness was formed from a certain stratum of living matter. The tension that arose at that moment in the inanimate stuff strove after a balance, and that resulted in the instinctual tendency to return to a lifeless state”50. If the ultimate goal of life is to reach death and the preservation instinct is only a partial deviation from this goal, its function is to serve the death drive, and this becomes evident in its inner dynamics of displeasure and destruction. In his Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, Freud had already expressed the constitutive character of sexual perversions in human subjectivity. In the context of his elaborations on the death drive, such primary processes (in which the polymorphous sexuality of origins is inscribed) appear as a sign of an inverted metaphysics in which death is the ultimate transcendence.

Of course, materialist metaphysics is no metaphysics at all for its rivals. In his ambitious book Metaphysics of Sex, Julius Evola regards the Freudian hypothesis of a death-drive as a merely biological (and therefore irrelevant) explanation of a phenomenon that deserves a much deeper approach51. The purified metaphysics of Eros that Evola attempts to delineate must also dispense with a specific phenomenology of the abnormal and the pathological, since such cases reveal for him the underlying substratum of so-called ‘normal sexuality’, which cannot be grasped by means of a profane approach. Evola strives to fully redress Freud’s materialistic subversion, turning the complex dynamics of love and aggression, pleasure and destruction, Eros and Thanatos, into a potential means of ecstatic transcendence52. But his ambition does not end there: he also rejects the conjunction of eroticism and ecstatic mysticism – in Christian saints like the Carmelite Mary Magdalene de’Pazzi or Margaret Mary Alacoque – as an impure and suspicious phenomenon which “does not have much to do with true spirituality”53. Orgiastic promiscuity, which Georges Bataille saw as a deeply transformative katábasis, is for him merely an intermediate phenomenon: it dissolves the limits of individuality in erotic excess, but it remains still too close to the type of union whose purpose is procreation54. A real metaphysics of Eros should begin with the conviction that human desire does not have its roots in the reproductive instinct, and that sexual attraction cannot be explained through psychological theories. The main fact of Eros, sexual attraction, is for Evola a mystery that can only be grasped if one focuses on the strictly metaphysical value of polar attraction (that is, a value to be found beyond both physical and psychological parameters) and the tendence toward the union of the opposites55. This radical position forces Evola to go even beyond the cosmogonic level of Eros (which is central in Daniélou’s divinization of eroticism) and cleanse the motif of immortality of any ‘telluric’ or ‘feminine’ aspect that might be attached to it56. From that perspective, the liquida voluptas surpasses the biological, psychological and daimonic-telluric domains to the point that any direct association with them would fail to do justice to the metaphysical significance of it: “the revelation of the fulgurating and destructive One”57. Led by the conviction that androgynous fullness – as undisputable alpha and omega of the erotic experience – is situated in the non-place of the transcendent One, Evola rejects not only any instance of erotic empowerment related to different forms of ritual performance but also homosexual love as a deviated and fictitious attempt at such completion58. The key to his metaphysics of sexuality is conveyed by means of a passage from the Bṛhadarāṇyaka-Upaniṣad, certainly quite different from the ones selected by Daniélou, and with a particular translation: “Not for the sake of the wife (in herself) is the wife desired by the man, but for the sake of the Self (the principle of ‘pure light, pure immortality’)”59. Even if the passage does not refer to erotic love [kāma] or passionate attachment [raga] but rather to being fond of [priya]60, Evola’s idea is clear enough: the root of desire is not in the object, but in the transcendent source from which both subject and object (as finite manifestations of life) arise, and that is the ultimate goal of erotic union. A purified metaphysics of Eros intends to re-conduct that power even beyond its cosmogonic origins, where it finally implodes.

Ritual scene of ass-kissing (XII century) at the Saint-Pierre-et-Saint-Paul de Troyes Cathedral. Source: Jean-Dominique Lajoux, Art profane et religion Populaire au Moyen Âge, Paris 1985.

Ritual scene of ass-kissing (XII century) at the Saint-Pierre-et-Saint-Paul de Troyes Cathedral. Source: Jean-Dominique Lajoux, Art profane et religion Populaire au Moyen Âge, Paris 1985.In a radical materialist metaphysics, the scope of sensuous delight (in Daniélou’s sense of volupté, i.e. ānanda) does not reach any pleromatic aisthesis; on the contrary it is reduced to an experience of lack and blind compulsion revealing that we – beings of desire – are a contingent deviation on the road to an inorganic and lifeless outcome. Its fundamental opposite, spiritual metaphysics, strives to render embodied experience with its contingent parameters and its plurality of beings fully impotent, degraded, or illusory in the face of a superior spiritus rector determining the ultimate goals of human behavior. It shifts the transcendent character of erotic rapture to the reverse-side of its experiential arena – out of which the erotic threads of sensuous delight appear devoid of any ontological value. Alain Daniélou’s divinization of eroticism may seem contradictory at first sight: what is the transcendence of Eros if it implies participation in a greater reality (called ‘divine’) which is mainly distinguished from ours in terms of intensity and not in terms of drastic ontological pairs like reality and illusion, principle and manifestation or truth and falsehood? We could say that his figure of transcendence is the spiral, in which there is no vertical architecture to account for relations among beings, but an expansive field. In this sense, his conception of the ‘supernatural’ is not topographical, but mainly energetic. Supernatural beings are relations we can have in different frequencies of intensity, and one of the parameters to bridge over the different frequency-levels is erotic rapture. In fact, the orgasmic culmination, irrespective of the form through which it is achieved61, is the most concrete and accessible energetic embodiment of the union of cosmic principles. Through specific techniques dealing with sexual energy, this intensity can be expanded to the whole of the energy-body, establishing thus a relation with the invisible and most inaccessible dimensions of Nature. This is even clearer in the case of what Daniélou calls sacred pharmacopoeia, the experiences of which – if properly controlled and framed in a sacred space – “lead to a contact with subtle beings and to the development of certain [special] faculties”62, like that of shamans. It becomes clear that the type of metaphysics purported by Daniélou tends to an immanent deployment and distribution of a multi-layered configuration of (human, non-human and trans-individual) energy. This energy breaks the boundaries of individuality and dislocates the field of experience from its rigid framework – not to remain aloof, but to return to Nature and disclose its unknown spheres. Even if unseen and mainly ignored (both by materialists and spiritualists), such spheres have an undeniable influence on our individual and collective behavior, so dealing with them means building bridges and enhancing the energy of the cosmic threads. There is a potential ars vivendi to be extracted from such a philosophy, the relevance of which (in our present context of global and ecological crisis) becomes more and more conspicuous. After all, worn-out metaphysical models (not only religious and spiritual but also secular) preserve an undeniable complicity with the ethnocentric and anthropocentric bent that is literally wiping out the diversity of the animated and living universe. Perhaps it is time to rescue Eros from its double imprisonment in the noetic and hyletic vaults of (proto-)history.

- “Man in his totality comprises the measurable as well as the unmeasured aspects of his being, and no account of him can be complete which does not comprehend the results of scientific measurement and relate it intelligibly to that which is unmeasured. But though incomplete, an account of man exclusively in terms of his unmeasured characteristics can be of highest utility […]. In order to be able to say something significant about man, one does not need to have had a special training” (Aldous Huxley, Proper Studies, London 1927, p. VIII).

- Cf. Georg Lukács, Die Seele und die Formen‚ Berlin 1911, p. 4.

- Cf. Antonio Gramsci, Quaderni del Carcere, volume secondo. Quaderni 6-11 (1930-1933), Torino 2001, p. 1375.

- Cf. Emile Cioran, Sur les cimes du désespoir [1932], in : OEuvres, Paris 1995, especially p. 17.

- Cf. Mircea Eliade, The Quest. History and Meaning in Religion, 1969, pp. 1-11, and Alain Daniélou, Shiva et Dionysos, Paris 1979, p. 294 It should be noted that the question of a ‘new humanism’ in Eliade is neither reducible to his political flirt with Romanian fascism or comparable to the totalitarian notion of a ‘new man’, however strong the mystical overtones of its ideological militantism of youth might be (cf. Michel Gardaz, Mircea Eliade et le « nouvel homme » à la chemise verte, in: Numen, Vol. 59, N°1 (2012), pp. 68-92).

- In order to emphasize the hybrid character of Eliade’s work, it suffices to consider his book The Quest: History and Meaning in Religion (1969), which contains a program to retrieve the religious ground of humanity by means of the study of non-European cultures, “both oriental and primitive” (Mircea Eliade, Ibidem, p. 3). Eliade’s conceptual pair (oriental/primitive) should draw our attention: oriental cultures like Brahmanism and Buddhism can hardly be equated with indigenous folk-groups like the ones characterizing Australian and Amazonian traditions. However, Eliade attempts an ontological synthesis by means of his ‘morphology of the sacred’. Thus, the field of so-called hierophanies imposes itself – as a kind of synthetic necessity – before any social structure or dynamics involving specific practices and relations.

- Cf. Mircea Eliade, L’épreuve du labyrinthe. Entretiens avec Claude-Henri Roquet, Paris 1978.

- Alain Daniélou, Hindu Polytheism, New York 1964, p. 5.

- Alain Daniélou, Shiva et Dionysos, p. 155. His words paraphrase the Bṛhadāraṇyaka-Upaniṣad 1.4.10. which reads tasmadeṣāṃ [devānām] tanna priyam yad etanmanuṣyā vidyuḥ [aham brahmāsmi]: “to those [gods] it is not pleasing that humans should know this [: I am Brahman]”.

- For a consideration of the choreographic function of the labyrinth and patterns of ecstatic dance in ancient times, cf. Hermann Kern, Labyrinthe. Erscheinungsformen und Deutungen. 5000 Jahre Gegenwart eines Urbildes, München 1999, p. 19

- It is also (though not exclusively) in this sense that we should understand Daniélou’s verdict on Shaivism as “essentially a religion of Nature” (Alain Daniélou, Shiva et Dionysos, p. 20).

- The passages from this Upaniṣad are taken from Alain Daniélou’s essay The Meaning of Gaṇapati, in: The Adyar Library Bulletin, Vol. XVIII, 1954, in this case p. 4. Part of this essay was edited and republished, together with some manuscript variants, in: Transcultural Dialogues, Issue 04, Spring Equinox 2020, pp. 18-26.

- An indication of this is that, in the same Upaniṣad, the salutation to Gaṇeśa contains the bīja mantra corresponding to the root-chakra [mūlādhāra]: oṃ laṃ namaste gaṇapataye (Daniélou, The Meaning of Gaṇapati, Ibidem, p. 3).

- Cf. the expression brahmadvāramukham in the description of the mūlādhāra cakra contained in Srī Pūrṇānanda’s Ṣaṭcakranirūpana, Verse 10 (Tantrik Texts, Vol. II: Shatchakranirupana and Pádukápanchaka, edited by Táránátha Vidyáratna, p. 18).

- Daniélou, The Meaning of Gaṇapati, Ibidem, p. 7.

- Alain Daniélou, Shiva et Dionysos, pp. 155-156.

- Cf. Daniélou’s considerations on prostatic orgasm and its relationship with initiatic rituals in: Yoga, Kâma: le corps est un temple, Paris 2005, pp. 190-191.

- The hedonistic dimension is not at all absent in Alain Daniélou, but his own divinization of eroticism, the most basic levels of which may attract the sexually obsessed, is not at all detached from a thorough reflection on the power of Eros and its individual, social and cosmic economy. Daniélou’s heightened awareness of the multi-layered threads of Eros makes it impossible to reduce his Shaivite-Dionysian philosophy – as some of his detractors have tried to do – to a projection of perverse phantasies or an apology of sexual debauchery.

- In the Bhūmikā-Sūkta of Atharvaveda (12.8.1.), the earth is referred to as ocean-born [ārṇava] and immersed in the primordial waters [salilamagna], precisely the inverted logic of the passage from the earth-chakra [mūlādhāra] to the water-chakra [svādhiṣṭhāna]. Daniélou’s interest in the fourth Veda is in this sense not at all anecdotical, since he saw a connection of aspects between the archaic practices of the forest ascetics and some elements of early Śākta Tantra – of the type he refers to with regard to Sāmkhya and Yoga: the individual experience displays a reversal of the cosmogonic process.

- Only a reformed Hindu agenda (and its heritage in the West) can deny the importance of the root-chakra for any operation related to Kuṇḍalinī Yoga. Even classical texts like the Ṣaṭcakranirūpana contain clear references to that aspect, like the following remark in Kalicharana’s commentary: raktapadmāntaropari ṣaṭśaktīnāṁ sthitiriti bodhyām [“the six śaktis should be regarded as situated upon the red lotus-leaf”]. Here the red lotus-leaf is the opening of the root-chakra, and the śaktis are forces of Nature personified as ambivalent female deities/demons who accompany the adept (with their concomitant transformations) in his progressive piercing of the chakras. These forces usually appear distributed in the different chakras according to their dominant element in each case, which can lead to the erroneous conclusion that they do not emanate from the earth but from some other subtle location. This primacy of mūlādhāra in different registers of the Tantric practice is confirmed in contemporary treatises on the subject, for example in Shyāmākānta Dvivedī’s Bhāratīya Śākti-Sādhanā (Vāraṇasī 2007, especially p. 101), where kula kriyā is explicitly related to the primacy of pṛthivītattva and the energy stemming from mūlādhāra.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Shiva et Dionysos, p. 11.

- Daniélou’s focus on an intensified and expanded aisthesis can be found in some contemporary thinkers with a remarkable elaboration and strong ecological bent, notably in David Abram: “The ‘real world’ in which we find ourselves […] is not a sheer ‘object’, not a fixed and finished ‘datum’ from which all subjects and subjective qualities could be pared away, but is rather an intertwined matrix of sensations and perceptions, a collective field of experience lived through from many different angles” (David Abram, The Spell of the Sensuous, New York 2017, p. 39).

- Alain Daniélou, Shïvaisme et tradition primordiale, Paris 2007, p. 43.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Shiva et Dionysos, p. 293.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Shivaïsme et tradition primordiale, p. 59.

- The isolation of the ātman in a sphere of purely introspective apperception can be compared to an absolute reduction of consciousness in a subtractive being, as one may read in one passage of Śaṅkarācārya’s introduction to his Brahmasūtra Bhāṣya when he writes aparokṣatvācca pratyagātma praṣiddheḥ [“one’s own self is well known to exist out of immediate presentation”]. The immediate character referred to in the passage is purely apperceptive, which means that it does not coincide with any of the conscious instances that fall within the empirical domain of one’s own self, but in opposition to a modern Western concept of pure apperception (as purely synthetic transcendental unity, cf. Immanuel Kant, Kritik der reinen Vernunft, B 132, Hamburg 1998, p. 178), it is furnished with an eminent ontological status.

- Alain Daniélou, La civilisation des différences, Paris 2003, p. 81.

- “According to the Shaivite texts, Shiva, the male principle, if devoid of the ‘i’ which is the shakti or power of the female principle, is merely śava (corpse), that is, the return to the neutral state conveyed by the non-manifested substrate” (Alain Daniélou, Ibidem).

- Bṛhadāraṇyaka-Upaniṣad 1.4.3. Daniélou quotes this Upaniṣad in different texts, such as Shiva et Dionysos, Shivaïsme et tradition primordiale and L’érotisme divinisé, notably also in Hindu Polytheism, whose philosophical section is built on a textual basis of the early and middle Upaniṣads.

- Cf. Govind Chandra Pande, Life and Thought of Śaṅkarācārya, Delhi 1994, pp. 202-203.

- Alain Daniélou, L’érotisme divinisé, Monaco 2002, p. 51. In Shiva and Dionysus, Daniélou points to the importance of samarāsa, that is, identification with the divine through sensation (cf. Alain Daniélou, Shiva et Dionysos, p. 200).

- Georges Bataille, Les larmes d’Eros, Paris 1961, p. 11.

- Georges Bataille, Ibidem, p. 21.

- In his Theory of Religion, Bataille defines the sacred as the “prodigious effervescence of life” [bouillonnement prodigue de la vie] (cf. Georges Bataille, Théorie de la religion, Paris 1973, p. 71), which leaves no doubt of the importance that the sacred character of eroticism has for him. This is the reason why he considered mankind’s progressive attempts to ‘frame’ or ‘civilize’ eroticism as a deceptive amputation of the sacred (cf. Les larmes d’Eros, p. 52).

- Cf. Georges Bataille, Ibidem, p. 34.

- Cf. Georges Bataille, Ibidem, p. 8.

- “The apparently hairy Neanderthal had knowledge of death, and out of this knowledge arose eroticism, which opposes the sexual life of humans to that of animals” (Georges Bataille, Ibidem, p. 20).

- Alain Daniélou, Shivaïsme et tradition primordiale, p. 83.

- “The creator is a cruel god who wanted a world in which nothing can survive without destroying life, without killing other living beings. No being can subsist without eating other forms of life, whether plants or animals. This is a fundamental aspect of the nature of created being” (Alain Daniélou, Shiva et Dionysos, p. 207). In the same passage Daniélou quotes Bṛhadāraṇyaka-Upaniṣad 1.4.6: etāvadvā idaṁ sarvam annaṁ caivānnādaśca [“All this (world) is but food and eater of food”].

- Alain Daniélou, La civilisation des différences, p. 87. In this passage, “accomplished like a rite” means with full awareness of its transindividual character and importance. The integration of ritual performance and sexuality in Tantra is barely dealt with by Daniélou, only fragmentarily (as in Shiva and Dionysus), allusively or between the lines (as in The Way to the Labyrinth), in spite of affirmations like the following: “the Tantric path, which makes the most diverse sacred rites out of sexual acts, is the truly mystical path through which we can apprehend the nature of the divine and come closer to the gods” (Alain Daniélou, Yoga, Kâma: le corps est un temple, p. 145). His references to the Tantric tradition are instead mainly cosmo-anthropological: he focuses on mantras, yantras and chakras rather than on the relationship between ritual and sexuality, cf. Le secret des Tantra, in: Alain Daniélou, Shivaïsme et tradition primordiale, pp. 139-152, and Notes sur le Tantra, in: Yoga, Kâma: le corps est un temple, pp. 119-120.

- Alain Daniélou, Ibidem, p. 42.

- It is clear that the term ānanda, already in Śaṅkarācārya, cannot be experienced in the sense of worldly pleasure – however intensified, trans-individual or cosmically related it may be (cf. Wilhelm Halbfass, Tradition and Reflection: Explorations in Indian Thought, Albany 1991, p. 255). This drastic division is enhanced and simplified in the reception of his thought. In the famous post-Śaṅkara formula saccidānanda (referring to the nature of brahman), for example, the term ānanda means clearly ‘spiritual bliss’ in the sense of a self-sufficient, a-cosmic, non-related ontological fulness.

- Examples abound. Suffice it to mention two of them. The first one is found in Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa 10.5.2.10: tau hṛdayasyākāsaṃ pratyavetya mithunībhavatastau yadā mithunasyāntam [“the two (Indra and Indrāṇī, that is, the male and female principles) descend into the space of the heart and engage in sexual union”]; the second in Bṛhadarāṇyaka-Upaniṣad 2.4.11.: evaṃ sarveṣāmānandānāmupastha ekāyanam [“the sexual organ is the convergence of all forms of delight”].

- The Taittirīya-Upaniṣad is explicit in this respect: prajātiramṛtamānanda ityupasthe [“procreation and immortality correspond to delight in the sexual organ”].

- Alain Daniélou, Yoga, Kâma: le corps est un temple, p. 139. Bataille shares this radical distinction between sexual act in the sense of procreation and erotic pleasure (cf. supra, note 36).

- Cf. Daniélou’s use of the term samarāsa (cf. supra, note 31).

- Sigmund Freud, Jenseits des Lustprinzips (1920), in: Studienausgabe, Band III: Psychologie des Unbewußten, Frankfurt 2001, pp. 213-272, quote p. 217.

- In fact, Freud indicates that the opposition between conscious and unconscious is not to be equated with that between ego and repressed contents: “Much in the ego is surely unconscious, already what we might call the core of the ego” (Sigmund Freud, Jenseits des Lustprinzips, Studienausgabe Bd III, p. 229).

- Sigmund Freud, Jenseits des Lustprinzips, Ibidem, p. 248.

- Sigmund Freud, Ibidem.

- Julius Evola, Metafisica del Sesso, Roma 2006, pp. 110-111. Evola focuses on the opposition between vital drive and death drive (cf. Evola, Ibidem, p. 111, footnote 47) without considering the fundamental asymmetry introduced by the compulsion to repetition in the psychosomatic dynamics and the metaphysical dimension of Freud’s reflection – in spite of Freud’s materialist and scientific attitude. This is quite understandable, since Evola operates with a prescriptive concept of metaphysics that excludes materialist variants altogether.

- “An algolagnia that is not compulsory experienced by perverts but consciously used by perfectly normal beings to intensify and expand, in a transcendent and eventually ecstatic sense, the possibilities contained in the current experience of sex” (Julius Evola, Ibidem, p. 115).

- Juluis Evola, Ibidem, p. 117.

- Julius Evola, Ibidem, p. 130. In Evola’s perspective, the ritual institutions of so-called ‘archaic societies” are degraded or clouded forms of a primordial tradition. Their cosmic-pantheistic character is closely related to an experience of the feminine divine (and its ambivalent Eros), which is to be distinguished from the highest, solar and masculine Weltanschauung in which he places his purified metaphysics of Eros.

- Julius Evola, Ibidem, pp. 42-43.

- Hence his critique of Ludwig Klages’ reflections on the liberation of the soul “not from the body, as man wrongly imagined, but from the spirit” (Ludwig Klages, Vom Kosmogonischen Eros, Jena 1941, p. 67, cf. Julius Evola, Metafisica del Sesso, p. 73) and even of Diotima’s analogy of the divine act of conjunction between man and woman with the act of begetting (Plato, Symposium, 206c: andrós kaì gynaikòs synousía tókos estin […] theîon to pragma, cf. Julius Evola, Metafisica del Sesso, pp. 74-75).

- Cf. Julius Evola, Ibidem, p. 89.

- Cf. Julius Evola, Ibidem, pp. 90-91.

- “Non per la donna [in sé] la donna è desiderata dall’uomo, bensì per l’âtma [pel principio ‘tutto luce, tutto immortalità’]” (Julius Evola, Ibidem, p. 69, footnote 6).

- The original text (Bṛhadarāṇyaka-Upaniṣad 2.4.5.) reads na vā are jāyāyai kāmāya jāyā priyā bhavati, ātmanastu kāmāya jāyā priyā bhavati. The passage enumerates many other instances of attachment, not only to a wife but also to a husband, to sons, to wealth, to being a brahman or a kṣatriya, to the worlds, the gods and other beings. The idea behind it is most probably that one is fond of something because it is similar to what has been experienced before, and none of the instances mentioned in the passage is previous to experience of the Self [ātman].

- Daniélou regards all variants of enhanced sensuousness as valid to achieve the type of transcendence related to Eros, including group sex, fellatio, and masturbation (cf. Alain Daniélou, Yoga, Kâma: le corps est un temple, p. 152).

- Alain Daniélou, Yoga, Kâma: le corps est un temple, p. 123.