Amanda Viana de Sousa

THE QUESTION OF ‘ANIMISM’ IN ALAIN DANIÉLOU

In this essay, Amanda Viana de Sousa approaches a central question in Daniélou’s work: animism. Through a historical reconstruction and a systematic analysis of this concept, she shows, in the first part of the essay, the radical change of connotation in the use of this term. The emergence of the new connotation is due both to the influence of the new anthropology (with its progressive critique of ethnocentric models) and to the increasing awareness of other modes of being (mainly in indigenous cultures) across the globe. The second part of the essay is a detailed analysis of a new understanding of animism in Daniélou’s thought, which in some ways is related to the radical transformation of that term between the end of the XX century and today.

Alain Daniélou performing a pūjā at Rewa Kothi around 1940 (archive of the Alain Daniélou Foundation).

Alain Daniélou performing a pūjā at Rewa Kothi around 1940 (archive of the Alain Daniélou Foundation).An Introductory Note on the Term ‘Animism

What does Daniélou understand by ‘animism’? What is the role of this concept within the framework of his work and thought? In order to answer these questions, it is first necessary to consider the origin and meaning of the concept of ‘animism’ in the context of anthropology.

Etymologically, the word ‘animism’ has its origin in the Latin word anima, which refers to breath, soul, life1. In philosophical and religious usage, the word anima refers to what distinguishes a living being from a non-living one. Anthropological usage has kept the etymological meaning to some extent, but it has also modified and expanded it with nuances and new layers.

If we take a retrospective look at the concept of ‘animism’, we notice that it was first introduced in the XIX century to convey the belief of ‘savages’ (a pejorative term used for indigenous people) in ‘souls’ or ‘spirits’ (both terms referring to ‘animated nature’). As such, the notion of animism came to be considered the elementary substrate of all religions. But at the same time, the term was associated with a defective type of reasoning and placed at the lowest level of civilization in human history2. This evolutionist view was further developed by stigmatizing the cognitive processes of ‘savages’ in their relation to nature, and also by assuming that animism is a superstitious practice inferior to science, whereas science is the best modality of relation between human beings and nature3. Even attempts of that period that opposed the evolutionist view proved to be problematic. Such attempts did not consider animism as an underdeveloped mode of (primitive) thinking, but rather as a synthetic and pre-logical mode of being, based on affections and mystical participation with the environment, thus defining and judging the life experience of indigenous peoples according to Western standards of logical thinking4. Even critique of the postulate concerning animism as the most elementary form of religion5 was judged problematic at that time: on the one hand it ascribed to animism the status of a complex cognitive process, while on the other, it confined it to the framework of an underdeveloped form of rationality6.

The XX century witnessed a revolutionary attempt to remove this concept away from the idea of a religious foundation with normative implications and define it as an ontology that describes a certain way of being in the world7. This implies a broader interpretation of the notion of person, its scope being subjectivity and relations encompassing both humans and other-than-humans (plants, animals, minerals etc.). Consequently, the expanded modality of interpersonal socialization propounded by animism includes a community far wider than humans. This new perspective of animism is drastically demarcated from the old one. In its worldview living beings know how to behave respectfully and properly towards all potential persons – “only some of whom are human”8. In other words, the ‘new animism’ does not take any being (whether human or other-than-human) ontologically for granted. Rather, it describes the process of relating in the best possible way with all beings, some of whom may become ‘persons’, according to the situation9.

In this conceptual context the idea of ‘animism’ is also an ontological opposite to ‘naturalism’ (that is, a world-configuration inaugurated with XVII rationalism and consolidated by Western industrialism in the XIX century, in which ‘nature’ is reduced to a domain of ‘soulless things’). The animist world-configuration presupposes a continuity of interiority (which accounts for subjectivity) and a discontinuity in physicality between humans and non-humans. This means that both humans and non-humans (plants, animals, and also invisible beings) have the status of ‘subjects’ and can never be reduced to ‘things’ (as is the case in ‘naturalism’)10. Both humans and non-humans perceive the world by physical means11, and since each embodiment is different, a physical discontinuity is established, essentially through their affective openness to the environment. In other words, the behavior, dispositions and capacities of a being are defined by its affective (embodied) constitution, not by the perspective it has, but the perspective it is12. One can clearly see the importance of the notion of ‘perspective’ in this new understanding of animism. The term shows that ‘nature’ as perceived by humans is not the only form of world-disclosure, and that ‘culture’ is not the exclusive property of humans13. Further, ‘nature’ is not precisely what Western science has defined in terms of objectivity. The ideology that emerged from that epistemic exclusivism has proved to be destructive when it comes to relating humans to nature, mainly because of the hierarchical division between ‘culture’ (high = work of the spirit and exclusively human) and ‘nature’ (low = lacking in spirit and therefore at the disposal of humans). Such a division allows all sorts of vertical schemes of domination and destruction in the name of ‘exploitation of resources’ for the sake of cultural progress.

The ‘new animism’ does not take any being, whether human or other-than-human, ontologically for granted.

An attempt has also been made to describe ‘animism’ as a ‘relational epistemology’: a cognitive, perceptual and social ‘relatedness’ between ‘persons’, not all of which are ‘human’. In this sense, certain persons are essentially connected with the specificities of a certain milieu14. This relational epistemology displays a mode of socialization between humans and non-humans based on a relationship of mutual dependence, significantly underlining an accurate and selective attention in the face of special incidents15. Because the new understanding of animism is so nuanced and has so many variants, we should perhaps speak about ‘animisms’ (using the plural) and avoid Western categories, such as ‘soul’, ‘spirit’, ‘subject’16.

Animism in Alain Daniélou

After these introductory remarks on the concept of animism, it is time to turn our attention to Alain Daniélou. In dealing with his approach, some relevant questions emerge from the contents exposed so far: What does Alain Daniélou understand by ‘animism’? Does he think of animism as the root of all religions? Does he consider it an ontology or an epistemology? Does his animist conception have evolutionist traits? Does he use animism, as we have seen in the case of the new scholarly approaches, as a critical examination of worldviews deemed ethnocentric or culturally biased?

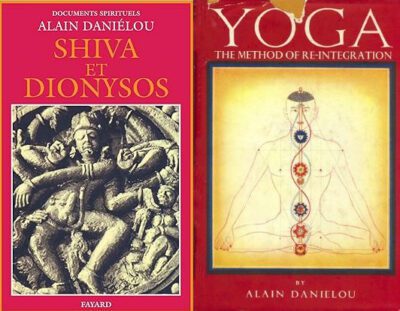

In my analysis of Daniélou’s concept of animism, I rely mainly on two of his books: Yoga: The Method of Re-Integration17 and Shiva and Dionysus18. In these books, Daniélou’s theses on animism are clearly expressed, and can be summarized thus:

- Animism is the foundation of all religions.

- Animism is a conceptual tool against urban religions.

- Animism is the most genuine expression of a ‘religion of Nature’.

- Animism is a kind of relational ontology and epistemology.

- Animism is the source of a religious phenomenon that he calls ‘Shaivism’.

I will devote the rest of this essay to an elucidation of Daniélou’s theses.

Animism is the foundation of all religions

In his book Yoga: The Method of Re-Integration, Daniélou presents animism in a certain way in agreement with the classical or old anthropological definition dating back to the XIX century. Animism appears as a worldview in which subjectivity is ascribed to the realm of nature19. In consonance with the old approach to animism (by XIX century anthropology), Daniélou believes that animism is the foundation of all religions. In his view, the religious practices of Christians, Muslins, Buddhists and Hindus are at root animistic, because they ultimately show a way of coping with a hidden and mysterious field. This mysterious field is ‘Nature’ in its non-objectifiable modality20. As opposed to the old approach to animism, Daniélou however regards it neither as an inferior stage in the development of religion nor as a naive, irrational or primitive attitude to the world. Animism removes the human being as the center of attention and does not take ‘nature’ for granted. Animism is the source of all religions because all religions reveal – implicitly or explicitly – manifold levels of non-human subjectivity and the human’s need for relation and negotiation with them21. In this sense, Daniélou claims that only some religions have remained faithful to their animistic foundations and have refused to reduce them by a restricted use of human reason. Such religions show not only an antidote to human alienation from nature but also the vital importance of a respectful exchange between humans and non-humans.

Animism as a Conceptual Tool against Urban Religions

In Shiva and Dionysus, Daniélou makes a fundamental distinction between a religion of nature and a religion of the city. In the frame of this distinction, he suggests that animism advocates an inner continuity between humans and non-humans. With this specific understanding of animism, Daniélou explains why a religion of nature includes non-human agency in the field of relations – which is not the case with urban religions22.

Urban religion is characterized by a dominant anthropocentrism – its clearest example being monotheistic religions. It operates using logical categories of human reason and derives three basic ideas: 1. The idea of a single God, source of all truth, who is pure intellect. 2. The peculiarity of the human species as made in God’s image, which is essentially related to being endowed with reason. 3. The devaluation of nature as something devoid of reason, incomplete, finite and objectifiable. For Daniélou, these basic ideas that characterize monotheistic creeds are rational speculations supporting ideological constructions, since they reduce ‘nature’ to a mere field of objects at the service of human ‘culture’23. As a result of this, urban religion disregards the complexity and relationality of all other living species, and it advocates the idea of a supernatural being, which inevitably leads to the alienation of humans from their ‘natural environment’. It is the transcendence or the supernatural (that is, what is beyond or above ‘nature’) that must be sought and emulated rather than nature as a field of immanent relations. A further consequence of this position is that human alienation ends up being considered a privilege of the spirit and nature is condemned as something imperfect. On the diametrically opposite pole we find the ‘true God’ and His absolute supremacy. This domination mechanism implies not only the exercise of human power over non-humans but also the affirmation of the moral superiority of humans – transmitted by means of specific dogmas elevated to universal laws24.

Daniélou uses the concept of animism to unmask the ideological character of the religions of the city. In this sense, the term ‘animism’ appears as 1. A worldview that recognizes the special position of non-humans as living beings endowed with intelligence, language, intentionality, etc. 2. A political instrument that underlines the interdependence and interrelation of all beings in a cosmic framework. 3. An anti-theological weapon against the devaluation and the objectivation of nature taking place in so-called ‘mainstream religions’. 4. The ground of all religions, though not as the lowest stratum in a process of evolution. On the contrary, animism appears as the most perfect expression of a ‘religion of Nature’.

In Daniélou’s expression ‘religion of nature’, two terms are combined and are worthy of attention, since they have become controversial concepts today: ‘nature’ and ‘religion’. Both terms are Western categories indicating a special relationship between humans and non-humans – a relationship quite alien to other cultures all over the globe in which such terms do not exist. Despite this semantic difficulty, Daniélou’s use of the expression aims at re-situating the notion of ‘supernatural’ within a field of immanence, as if he wanted to retrieve the hidden and mysterious dimension of nature that monotheistic religions and later scientific reductionism have progressively excluded from the field of human experience25. He also describes a certain experience of nature in non-European cultures, in opposition to the alienating practice of urban religion.

Samaúma, a powerful sacred tree for the indigenous people of the Amazonian rainforest (photo by Amanda Viana, 2022).

Samaúma, a powerful sacred tree for the indigenous people of the Amazonian rainforest (photo by Amanda Viana, 2022).Animism as the Most Genuine Expression of a ‘Religion of Nature

In Alain Daniélou’s thought, the religion of nature does not imply a connection with a transcendent God, but rather the development of an attitude in which the human subject opens itself to the possibility of communication and interaction with the ambivalent forces of nature. This attitude is mainly expressed on the level of perception. Both non-human beings and human animists are in a permanent negotiation with both the visible and the hidden levels of their environment – none of which is the object of abstract cognitive processes. Both non-human beings and human animists have not only an awareness of the invisible landscape of their environment (spirits, forces, gods, etc.), but they also notice and heed what is necessary for their survival and can sense natural disasters beforehand. They never violate the cosmic order, because they are instinctively aware that no action is without consequence26.

The animistic foundation of this form of religion demands a constant attention to the sacred and ambivalent character of nature. For Daniélou, nature is ‘sacred’ because it can neither be fully grasped by the human intellect nor reduced to anything objectifiable (material resources, scientific objects, experimental field of modern technologies, etc.). It is also ‘ambivalent’, because no moral principle regulating human conduct can be projected onto it to account for its sometimes baffling complexity. Within that context, non-human agency is an expression of the divine and in no way outside the realm of subjectivity. The animist mode of living is an authentic and unquestionable religious experience per se, in which the intersubjective relation between humans and non-humans plays a central role. Alienation from nature (as in the case of the religions of the city) is not only a disconnection from life but also a profanation of the sacred, a desecration of the divine, and ultimately a threat and a great danger for the human species27. Daniélou’s conception of animism is no sentimental plea for a utopian re-connection with nature (of the type that we can see in New-Age movements today), but rather an exhortation to ‘modern man’28 to re-discover his own place in a world that is simultaneously dynamic and manifold, beautiful and cruel29.

Animism as a Relational Ontology and Epistemology

The permanent and necessary negotiation between humans and non-humans presupposes a specific form of interconnection. In Daniélou’s approach to animism, the inner continuity between humans and non-humans displays their mutual dependence. This aspect comes very close to what post-modern anthropology terms ‘relational ontology’. In Shiva and Dionysus, Daniélou writes: “The mineral, vegetable, animal and human world as well as the subtle world of spirits and gods exist one through all the others, and each one for all the others”30. These words show that Daniélou advocates the vision of a cosmic architecture or a dynamic and coherent whole, where human beings cannot arbitrarily impose their will upon others. Daniélou defines their role as a humble and active participation in the divine harmony. Human beings should contribute to the preservation of a socio-cosmic order in which they have no special privilege31. In this regard, he writes: “When humanity as a whole becomes a threat to other species, the gods instill madness in them, which leads to their destruction in order to preserve the natural balance”32. In other words, when man reduces the mystery of life to his instrumental reason, he becomes the enemy of “the gods and creation”33. Daniélou is convinced that only a religion of Nature (which he terms ‘Shaivite-Dionysian’) can lead to an harmonious interaction between humans and non-humans, and the animistic attitude is the basis for such a type of dynamics:

“Neither purely moral nor just ritualistic, but ecstatic and close to nature, this [Shaivite-Dionysian] religion tries to find the points of contact between the different levels of being and to seek their harmonious interaction – something which allows everyone to realize themselves on the physical, intellectual, and spiritual level and to entirely play their own role in the universal symphony of the manifest world”34.

Apart from the ontological aspect and ethical consequences of animism, Daniélou refers to what in contemporary anthropology is called ‘relational epistemology’. As mentioned above, animists have an expanded perception that reaches the subtlest levels of reality, a special kind of intuitive knowledge enabling them to identify subjectivity in mountains, springs, rivers and forests, and to engage in a relationship with them35. The result of this is a careful and empathic respect for the subjectivity of non-humans and a vehement opposition to “the appropriation, possession and exploitation of the earth, which destroys the natural order and postulates man as the lord of creation”36.

We may therefore say that Daniélou’s understanding of animism entails an onto-epistemological interdependence between humans and non-humans, from which emerges a clear hostility against every form of ‘institutional alienation’ – regardless of its being monotheistic or secular.

Animism as Source of the Religious Phenomenon called ‘Shaivism’

For Daniélou the greatest expression of a religion of Nature is Shaivism37. In this respect, he writes: “Shaivism is that great religion that emerged from the animistic conception and the long religious experience of prehistoric man, about which we otherwise have only a few rare archaeological signs and references”38.

Shaivism is, in its very roots, animistic, because its field of experience is nurtured by an archaic, unpredictable and powerful force39. In its practical dimension, it is closely connected with the forest and the mountains40, it opposes the anthropocentrism of urban societies41, it postulates an interdependence between the different levels of being (or the multiplicity of life forms),42 and it does not accept any dichotomy between the natural and the supernatural, nor does it postulate an ontological separation between humans and non-humans.43

Daniélou resorts to Puranic sources to validate his own view of the god Shiva44. In some of the Mahapuranas, Shiva is closely connected with a power of expansion and dispersion, i.e. he is characterized as the principle of life and death: “Shiva is the force of expansion in the world and is thus the energetic source of existence and principle of life, but also, since expansion ends in complete dispersion, the principle of dissolution and death. Everywhere and in everything, whatever causes life and death reveals Shiva’s nature and is his ‘sign’”45.

Shiva acts – in a broader sense – as a cruel god, and his cruelty teaches us fundamental aspects of life. One of these aspects is the concrete awareness that no living being can survive without destroying and devouring other forms of life46. At the same time, Shaivism not only expresses but also upholds a living continuum entailing humans and non-humans. In Daniélou’s words:

“Shaivism […] is the sum of human experience since immemorial time. Its non-dogmatic traits allow people to find their own way. […] Its ecological aspect (as one would say today) regards humans as part of a whole in which trees, animals, people, and spirits are related to one another and should live in mutual respect […]. It is completely opposed to the destruction of nature and its different species […]. It does not separate intellect from body, spirit from matter, but it sees the universe as a living continuum”47.

Shiva incarnates the totality of Life and permeates the manifested reality. For Daniélou all natural phenomena, living beings, and intrinsic qualities of human life (for example its physical, emotional and cognitive faculties) are part of Shiva’s body and can serve as a way of reaching the divine48. But since Shiva is a ‘dangerous god’, he grants access to a form of knowledge that can only have its source in an unpredictable experience49. For this reason, Daniélou advocates specific religious practices related to Shaivism that may serve in accepting and even embracing the ambivalent character of life, thus leading to a deeper understanding of the cosmos50.

For Daniélou the greatest expression of a religion of Nature is Shaivism.

Another special aspect of Daniélou’s conception of animism is, as already mentioned, the continuity he postulates between humans and non-humans on the level of their perceptive faculties. A peculiar feature of this is that perception does not appear as a lower faculty, but quite the opposite, as something endowed with a kind of noetic power – a power that enables a profound understanding of reality even before analytic processes are carried out. This aspect goes hand in hand with an affirmation of the body51.

Front cover of Alain Daniélou’s Shiva et Dionysos (Paris 1979) and Yoga: The Method of Re-Integration (London 1949).

Front cover of Alain Daniélou’s Shiva et Dionysos (Paris 1979) and Yoga: The Method of Re-Integration (London 1949).Daniélou criticizes religious practices that reject the body and isolate the soul as an exclusively privileged channel to reach the divine. He categorically claims that religious practices based solely on spiritual experience devoid of every instance of embodiment lock themselves up in abstractions and alienate themselves from the true interactive field of forces that is Nature. Even when the body appears as a consistent starting point for the experience of the divine52, in itself it does not guarantee anything. For Daniélou physical awareness of the divine presupposes a re-education of sensation and perception53. Within the field of Shaivism, there are methods – a certain number of Yogic and Tantric practices – that lead to the expansion of perception by breaking the barrier of human reason54. It is in this way that the connection of humans with subtler levels of being becomes possible,55 as well a religious socialization of humans with non-humans. Daniélou was convinced that some methods and techniques practiced in Shaivism may contribute to the development of an animistic attitude towards the world56. In this sense, Shaivism appears as a way of integrating every aspect of manifest reality (including its chthonic or tamasic powers) to make human experience broader, richer, and more intensive. But most of all, it leads to an enhanced responsibility of humans in their way of dealing with nature57.

- Cf. Julius Gould und William L. Kolb (Hg.): Dictionary of the Social Sciences, New York, 1965.

- Tylor, Edward, 1913 (1871). Primitive Culture I, London: John Murray, p. 426-7. Cf. Graham Harvey. Animism. Respecting the Living World. London: C. Hurst & Co., 2005, p. 6-9.

- Frazer, James G., 1983 (1860). The Golden Bough, London: Macmillan, p. 146-147. Cf. Graham Harvey, 2005, p. 5.

- Lucien Lévy-Bruhl. La mentalité primitive, Paris 1922, p.76-80, 84, 86, 87-88, 121.

- In this model, animism does not attain the status of a religion, since it is not a system of convictions and practices.

- Émile Durkheim. Les formes élémentaires de la vie religieuse, Paris 1912, p. 125.

- Graham Harvey 2005, p. 20. Cf. Graham Harvey. “Animism rather than Shamanism: new approaches to what shamans do (for other animists)”. In: Schmidt, Bettina and Huskinson, Lucy eds. Spirit Possession and Trance: New Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Continuum Advances in Religious Studies (7). London: Continuum, 2010, pp. 14–34, here p. 4-5. Jenny Nerlich. „Neue Betrachtungen eines evolutionistischen Begriffes“. Open Edition Journals: Zeitschrift für junge Religionswissenschaft. 15/2020, p. 7.

- Graham Harvey, 2005, p. xvii.

- Cf. Graham Harvey, 2005, p. 18.

- Cf. Eduardo Viveiros de Castro. The relative native. Chicago: Hau, 2015, p. 245. Cf. Viveiros de Castro. “Die kosmologischen Pronomina und der indianische Perspektivismus.“ Societé Suisse des Americanistes 61, 1997, p. 99-114; p. 103.

- Cf. Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “Perspektiventausch: Die Verwandlung von Objekten zu Subjekten in indianischen Ontologien”. In: Animismus. Revisionen der Moderne, hrsg. Irene Albers und Anselm Franke, Zürich: Diaphanes, 2012, pp. 73-93; here p. 83-84.

- Cf. Viveiros de Castro, 2015, p. 257; Viveiros de Castro, 1997, p. 107.

- In the development of the conception of animism, one should not forget the nuance introduced by perspectivism: while in animistic systems cum perspectivism humans and non-humans see themselves and their equals as ‘humans’ and other species as ‘non-humans’, in animistic systems sine perspectivism both humans and non-humans see themselves and the other species as ‘humans’. Cf. Philippe Descola. Par-delà nature et culture. Paris: Gallimard, 2005, p. 249 and Nerlich, 2020, p. 10.

- Cf. Nurit Bird-David. “Animismus revisited: Personenkonzept, Umwelt und relationale Epistemologie”. In: Animismus. Revision der Moderne, hrgs. Irene Albers und Anselm Franke, Zürich: Diaphanes, 2012, pp. 19-47, here p. 23.

- Cf. Bird-David, 2012, p. 43-46.

- Cf. Bird-David 2012, p. 23 and p. 33.

- The first edition of Yoga: The Method of Re-Integration was published in 1949. The book was republished in English with the title Yoga: Mastering the Secrets of Matter and the Universe. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions, 1991.

- This book was published for the first time in French: Shiva et Dionysos (Paris: Fayard, 1979). The first English translation kept the title of the original: Shiva and Dionysus (London and The Hague: East-West Publication, 1982). Subsequently, English-speaking publishers opted for a somewhat different title: Gods of Love and Ecstasy. The Traditions of Shiva and Dionysus (New York: Inner Tradition, 1992). In 2020 a critical edition was published in German: Alain Daniélou. Shiva und Dionysos. Die Religion der Natur und des Eros. Aus dem Französischen übersetzt von Rolf Kühn, überarteitet von Sarah Eichner und herausgegeben von Adrián Navigante. Dresden: Text und Dialog, 2020.

- Cf. Daniélou, 1991, p. 8.

- Cf. Daniélou, 1991, p. 8.

- Cf. Daniélou, 1991, p. 8 and p. 9.

- Cf. Daniélou, 2020, p. 57-58.

- Cf. Daniélou, 2020, p. 58-59.

- Cf. Navigante, Einleitung. In: Alain Daniélou. Shiva und Dionysos. Die Religion der Natur und des Eros, 2020, p. 16-17. Some historical consequences of the monotheistic worldview are violent evangelization, holy wars, colonialism, dogmatic imperialism, a patriarchal persecution of the erotic, the witch trials, and the massive destruction of nature ensuing from the idea of a radical transcendent God.

- Cf. Daniélou, 1991, p. 8: “Modern religions have reached an extremely simplified concept of the supernatural by seeking to reduce everything to a single personified being, a single god resembling somewhat the chief of a tribe”.

- Cf. Daniélou, 1991, p. 8. Cf. Daniélou, 2020, p. 74.

- Cf. Navigante, 2020, p. 16-17.

- Cf. Daniélou, 2020, p. 74.

- Cf. Daniélou, 2020, p. 56 und p. 74-75.

- Cf. Daniélou, 2020, p. 55 (my translation).

- Cf. Daniélou, 2020, p. 52 and p. 56.

- Cf. Daniélou, 2020, p. 51 (my translation).

- Cf. Daniélou, 2020, p. 58 (my translation).

- Cf. Daniélou, 2020, p. 49 (my translation).

- Cf. Daniélou, 1991, p. 8, p. 10 and p. 11.

- Cf. Daniélou, 2020, p. 74 (my translation).

- Cf. Daniélou, 2020, p. 55 and p. 60. Cf. Daniélou, 2006, p. 43: “Shaivism is a religion of nature which tries to perceive the divine in its work and to integrate itself into it” (Alain Daniélou, “Le renouveau shivaïte du troisième au dixième siècle”, in: Shivaïsme et tradition primordiale, Paris 2006 [first edition 2003], pp. 37-67, quotation p. 43). Cf. Navigante, 2020, p. 23.

- Cf. Daniélou, 2020, p. 82 (my translation).

- Cf. Cf. Daniélou, 2020, p. 60. Cf. also Navigante, 2020, p. 24-25.

- Cf. Daniélou, 2020, p. 60, p. 200.

- Cf. Daniélou, 2020, p. 60.

- Cf. Daniélou, 2020, p. 55.

- Cf. Daniélou, 1991, p. 9 and p. 10.

- Cf. Daniélou, 1991, p. 14: “Apart from the Purânas, which are histories, the basic aspects of Shaivite philosophy, rites, and symbols are found in numerous other works known as Âgamas and Tantras”.

- Cf. Daniélou, 1991, p. 15.

- Cf. Daniélou, 2020, p. 131, p. 132, p. 196, p. 240, p. 241, p. 242, p. 248 and p. 250. Cf. also Daniélou, 1991, p. 8, p. 9, p. 14 and p. 15.

- Alain Daniélou, Brief an Michael. Auty, Dezember 7, 1997, Archiv. Alain Daniélou, Zagarolo, Italien (Cf. Navigante, 2020, p. 42).

- Cf. Daniélou, 2020, p. 56.

- Cf. Daniélou, 2020, p. 60.

- Cf. Daniélou, 2020, p. 63.

- Cf. Daniélou, 1991, p. 2, p. 7, p. 8 and p. 9.

- Cf. Daniélou, 1991, p. 7: “The pleasure of taste, smell, touch, sight, hearing, and sex can, on the other hand, lead to the perception of divine harmony through beings and things. We are very close to the Divine in our moments of enjoyment, love, and contemplation of beauty. If we wish to go still further and perceive the inner harmony that presides over form, it suffices to go beyond the senses. It is in our own body, at the very source of enjoyment and not of thought, that we can attain the creative principle of the world. Corporal, not mental, techniques allow us a foretaste, at the very bottom of our being, of that Absolute of which we are merely fragmentary manifestations, since “the space inside the jar is not by its nature distinct from the immensity of space.”

- Cf. Daniélou, 1991, p. 8, p. 10, p. 12 and p. 24.”

- Cf. Daniélou, 1991, p. 12 and 15.

- Cf. Daniélou, 1991, p. 9 and p. 16.

- Cf. Daniélou, 1991, p. 9: “According to the chronology of the Purânas (ancient chronicles), it was towards the sixth millennium before our era that he who among the gods presides over life and death revealed to mankind the means to pass beyond the limitations of sensory perception and to know by direct and extra-sensorial experience the subtle nature of the natural apparent world and its transcendental aspects, which are the gods and spirits. The technique of this experience is called yoga (‘the bond’), of which our word ‘religion’ is a translation.”

- 57 Cf. Navigante, 2020, p. 24.