Gioia Lussana

WHERE BEAUTY BLOSSOMS*

In this essay, Gioia Lussana approaches the relationship between aesthetic experience [rasāsvāda] and religious experience [brahmāsvāda] in the context of the medieval non-dual Śaivism of Kaśmīr. Focusing on the Abhinavabhāratī, Abhinavagupta’s commentary to the Naṭyaśāstra, as well as on Raffaele Torella’s recent studies on that text, Gioia Lussana explores the modalities and intricacies of the perception of beauty – even as part of everyday life experience which, in the inclusive view of non-dual Tantrism, also hosts the potential to generate beauty.

* This essay is the revised version of a chapter of the book Lo yoga della bellezza. Spunti per una riformulazione contemporanea dello yoga del Kashmir (Om Edizioni 2021), the fruit of a grant received in 2019 from the Alain Daniélou Foundation (FAD). It is dedicated to Raffaele Torella, mentor and inspirer of my work.

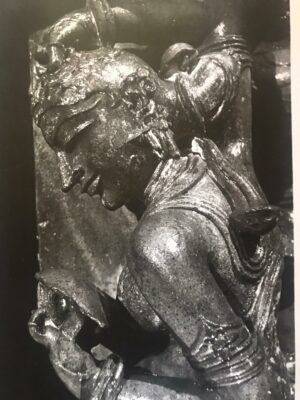

VI century Naṭarāja relief at the Badami Cave temples (courtesy Laura Giuliano).

VI century Naṭarāja relief at the Badami Cave temples (courtesy Laura Giuliano).“L’Amour est descendu par amour dans ce monde sous forme de beauté” (Simone Weil, Cahiers)

vAbhinavagupta, in a crucial passage of the first chapter of his Abhinavabhāratī1, refers to the various possibilities of cognitive activity [pratyaya] in the human being. The first form of knowledge of reality is the ordinary sort [laukika] that distinguishes the limitedness of saṃsāric experience. In it, the individual is almost a hostage to objective reality, to which he reacts with a predatory attitude, to exorcise, through domination, his own dependence from it and to impose, overbearingly, his own egoic identity. Such a procedure, prevalent in daily life, leaves no place for beauty which, to be evoked, requires a free space between the knower-subject and the known object.

This space emerges in the second possibility of knowing the world, that of the enjoyer of art (homo aestheticus), which occurs through rasa, aesthetic emotion. Indeed, beauty can burst forth only in the crucible of an interactive space between subject and object, the space of freedom rather than of need or control. Then egoic coercion ceases to impose itself on this or that object and – by virtue of what the great Kaśmīri master denominates ‘the universalisation of experience’ [sādhāraṇībhāva] –beauty can be enjoyed gratuitously, like a flower that blossoms spontaneously in the midst of an ownerless garden.

Then there is the perceptive and cognitive quality typical of yogic experience [yogi-pratyakṣa]2, a heightened degree of cognition, which also provides a space of contemplation between itself and the object, as also an unfiltered view of what one wishes to know. Abhinavagupta examines two different levels of this cognitive mode. The yogin of a lower level is no longer at the mercy of his own ego like the ordinary man; but his knowledge lacks beauty however, which, to reveal itself requires not only an immediate and direct perception of reality – generally speaking, the distinguishing mark of yogic perception – but a further element missing at this level: a spark of empathy by the subject toward the object of his knowledge. This is not within the reach of this yogin, because he is too ‘detached’ for his heart to beat fervidly in unison with life. The siddhi, or supernormal abilities that he has acquired through yogic discipline, act as a screen for the inner affective coloration that triggers and illuminates the immediacy of beauty.

Using the classification recognised by the Kaśmīri schools, this kind of yogin belongs to the coarse level of techniques [sthūla-dhyāna or āṇava-upāya]. Through the various means of yoga he has developed powers (such, for example, that of reading others’ minds)3 which somehow makes his perception ‘opaque’, because it remains uninvolved and unactivated in what it perceives. Such a yogin’s mastery of the elements of the real in actual fact involve a sort of indifference [tāṭasthyā] towards all things. In him there is no trace either of the attachment that distinguishes the ordinary man, or of that special empathy freed from the egoic components typical of aesthetic experience. This means that the flame of vibrant energy, always a priority in the non-dual Śaivite context, is not alight within his heart. This lower kind of yogin is taṭastha, unconcerned, like ‘the one who stands on the bank of a river and lazily observes its flow’, without throbbing to the rhythm of existence.

Beauty can be enjoyed gratuitously, like a flower that blossoms spontaneously in the midst of an ownerless garden.

In the context of this work, Abhinavagupta also considers the para-yogin or yogin of a superior level, equally unable to pick beauty since he is too distant from human passions and wholly identified, not with human events in this case, but with the Absolute itself. If, however, we interpret coherently the thought of the great Kaśmīri master in the light of the spiritual view that emerges in all his work and in non-dual speculation as a whole, we could argue that the high-profile yogin cannot pick it because he actually embodies the supreme form of beauty. The highest expression of yoga, often characterised as para-dhyāna, śāmbhava upāya or even anupāya (wholly spontaneous yoga, beyond all technique), actually coincides with that condition of intimate bliss [svānanda] intrinsic in brahmāsvāda, tasting the Absolute. It represents the maximum achievement of non-duality, as Abhinavagupta states elsewhere, as for example in the Locana, his commentary on the work of Ānandavardhana4. Here, aesthetic tasting [rasāsvāda] is explicitly described as a mere drop of that overflowing bliss that is the savouring of the Absolute [brahmāsvāda]. Here, the adept, in the ecstasy of experience, recognises himself as identical to Śiva, the ‘supremely beautiful’5. No longer coloured [uparāga-śūnya] by outside influence, but nonetheless trembling and bewitched by the Absolute in an ardent embrace that includes everything. In a word, it can be said that, considering the Absolute (Śiva) as Beauty itself, the aesthete perceives beauty wherever the para-yogin becomes it6.

In the dimension of brahmāsvāda, this space of separation and energetic tension between subject and object that marked rasāsvāda (and generated the perception of beauty) is replaced – in this interpretation – by what we may call a pulsating integration between subject and object which amalgamate in mutual intensity, without ever losing that live spark that is spanda, which in Śaivite transmission moves life and awareness. The two poles, like those of a generator (i.e. the human and the divine), never disappear, but mutually energise each other like tongues of a single flame. In the integrated condition of brahmāsvāda they are, on one side the yogin / bhakta and, on the other, the God, to whom the adept is always alert in an impetus of fervent devotion. Within this inscrutable relationship is released the glow of a live connection.

The para-yogin, whose ego has divested its arrogant rapacity toward the real, then experiences a paradoxical ‘ardent neutrality’, similar to rasāsvāda, but enormously enhanced by the mutual increase of the two poles of experience. We could compare this otherworldly state [alaukika] to what R. Torella defines as a kind of “hyper-saundarya”, a ‘super-beauty’, an experience that is highly unifying and vital at the same time, in which the subject contemplates itself in the object of that awareness that is Śiva himself and the God contemplates himself in him. This aesthetic experience thus constitutes an effective training, marked moreover by its own self-sufficiency, in the irruption of spiritual beauty, its direct extension, albeit autonomous and not automatic in its regard. In this situation, any form of fruition may become an occasion of awakening and, as such, a reverberation of the Absolute which, on its side, is solely pure, conscious bliss.

Through a kind of alchemic transmutation, not only pleasure, but even the pain of life – as well as life’s own routine – can be transformed into an experience of savouring. Saṃsāra is transformed into nirvāṇa, or rather, the fictive barrier between them falls away. Yoga becomes life, savoured in all its luminous beauty, even in what appears negative, painful, obscure.

Going on to the non-dual conclusion of these considerations, ordinary, aesthetic and religious perception are in any ultimate analysis equally expressions of the divine (meaning ‘supreme beauty’). I have personally been able to establish directly to what extent all this is true in present-day Kaśmīri yoga.

Yoga becomes life, savoured in all its luminous beauty, even in what appears negative, painful, obscure.

A contemporary Indologist, M. Hulin, points out that daily life itself may present sudden and unexpected irruptions in this spiritual bliss which, by approximation, we may call beauty7. Hulin observes that even in everyday life glimpses of a mysterious or mystical dimension are spontaneously accessible – and sometimes even gape open – often triggered by the most banal situations, without any precise or apparent cause. Happiness (and with it the expansive quality of beauty) sometimes irrupts in a self-explanatory and self-sufficient way, even under saṃsāric conditions, suddenly eclipsing all the limitations of ego and space-time that structure our ordinary existence in the world. This happiness offers itself through an ecstatic emotion, as sudden as lightning that lightens the night sky, without any explicable relationship to the eventually apparent irrelevance of the situation that triggered it.

Apsarā in loving attitude – Adinath Temple, Khajuraho (photo Raymond Burnier, archive of the Alain Daniélou Foundation).

Apsarā in loving attitude – Adinath Temple, Khajuraho (photo Raymond Burnier, archive of the Alain Daniélou Foundation).Kaśmīri masters exclude, from a theoretical point of view, any perception of beauty in the bustle of ordinary existence, since it always requires a discreet degree of revival of the attention fostered by a space of contemplation. But in the substance of non-dual speculation, even daily existence is not ultimately substantially different from absolute reality so that flashes of savage beauty can also be suddenly revealed there too. Kaśmīri Śaivism, while considering rasāsvāda and brahmāsvāda as two privileged conditions of knowledge as compared to customary somnolent perception, never undervalues the living experience of so-called ordinary reality, because whatever exists is merely the free expression of Śiva’s dance and every situation contains the potential of awakening, like that of a flower that grows spontaneously even outside the pot or garden.

In line with these considerations, Abhinavagupta affirms8 that even what we call ‘things’ [bhāva] are alive: they ‘feel’, they share with human beings the potential of awakening. It is actually they that ‘move’ men’s actions. Things possess a determining capacity, an intelligent creativity and can bring about different states of mind in man. According to the non-dual view, there is thus an actual real reciprocity in the relations between the human being and the world of objects, as equally ‘animated’ as the subject they serve. It is the very will to possess things – typical, as we have seen, of the despotic attitude of ordinary man – that precludes perception of the souls of all things. The heart of things is profound and alive, because it contains within it the spark of the divine, which is everywhere, albeit dormant, shielded, by the density of the objects themselves9. In Abhinavagupta’s concept, things are merely more humble and less intrusive than their observers and users, but they are equally proactive and desirous of interacting with the iridescent game that is life in its every expression. Not only in the human being, but also in things, moves spanda, the vibration of consciousness, whether one is aware of it or not. In the contemporary reformulation of Kaśmīri yoga we are constantly invited to listen to ‘the heart-beat’ by carefully exploring whatever seem inert in the body, but which reveals unexpectedly and whenever it chooses its own hidden vitality.

Continuing with my revaluation of the world of objects in the non-dual Śaivism of tradition, during my recent study-visit to contemporary Kaśmīr and from my talks with Pranāthji, the master whom I have had the fortune to encounter, I learned of the central role in the living transmission of Kaśmīri yoga played by ‘contemplation in action’. ‘Things’, like daily activities, whether dense or multiform, while actually veiling the luminosity of awareness, nonetheless hold that same light within them. In the end, they seem to have been planted there to render the mystery of existence more various, constantly inviting and challenging us to reawaken. The transforming encounter with objective reality may thus even disregard strictly ritual time. The world of objects then appears worthy of respect, care, attention, and of being listened to. Things are no longer just things, but presences prompting an inner dynamism. This correspondence with things spontaneously triggers ‘the posture’, i.e. that vibrant inner disposition, yoga’s beating heart in a wider sense, that is also life lived to the full, apart from specific ritual practice.

The unhurried prompting of a non-appropriative relationship between oneself and the world simplifies the field of perception, allowing only the essential to emerge in all its brilliance. Attention awakens and feeds the exchange between oneself and things. Its mutual intensity renders this exchange fervid and fruitful.

Transformation of the gaze leads to a ‘loving consensus’ with things which, from an ephemeral present, rise to become the vehicle of eternity.

Things are capable of opening wide their universal nature, also seen as evident by Marcus Aurelius10, heir of the Stoics, at the outset of Western mystical philosophy. In his ‘physical’ contemplation of the world of nature, Marcus Aurelius speaks of ‘indifference towards indifferent things’, not because they lack interest for the observer or for their indifference in itself. In actual fact, they involve the subject in a reciprocal complicity, but are independent of man’s will and thus go far beyond his limited understanding. Things must be ‘left free’ from personal involvement, free to unfold their own universal nature (sub specie aeternitatis). Their ‘indifference’ with regard to anthropocentric usefulness thus reveals to the sage an infinite interest, revealing love, beauty and admiration. Such things are then transfigured and open the horizon to an infinitely greater will that even includes their observer himself. Transformation of the gaze leads to a ‘loving consensus’ with things which, from an ephemeral present, rise to become the vehicle of eternity. This is how the ordinariness of the natural world opens to become an aesthetics ‘of daily things’, in which everything reveals its authentic beauty11.

Yoginī – Hirapur Temple, Orissa (photo Gioia Lussana).

Yoginī – Hirapur Temple, Orissa (photo Gioia Lussana).The great mystics, like the ‘mystics of daily life’ have never undervalued relations with things, sometimes the minor things of daily life, discovering in them a silent support for innerness. E. Hillesum,12 a natural mystic, in his penetrating diary prior to his deportation and death at Auschwitz in 1943, describes the possibility of experiencing amorous rapture for Spring, or of befriending Winter, or a city, or a countryside. She describes, for example, special feelings towards a plant, the copper beech tree of his childhood, the feeling of enchantment and nostalgia for that element of nature. I can personally recall a pregnant daily exchange with a rose bush, during a long meditational retreat, and in every month of May I rediscover that same inspiration of dialogue with the roses of my garden. Silence sometimes favours the perception of the vastness that encompasses us, of which we are merely a part. A breath that breathes us, a thought that thinks us.

Thus we can affirm that the spontaneous spiritual awakening envisaged by Kaśmīri yoga is something to which everyone is already intrinsically predisposed. It comes however like an uncalled for and sudden grace, but it is evoked and mysteriously prepared by constant training of attention, ‘gracious’ and participant in our daily relations with things. We can find the same kind of grace in aesthetic experience or in strictly defined yogic gesture. It may be perceived as something fragile, which a single moment’s distraction may sweep away, but it is rooted in the deepness of being.

Grace is revealed as a privilege of homo aristocraticus, by which we mean not exactly the rājānaka or ‘man belonging to court nobility’ – a category to which Abhinavagupta and the other Trika masters belonged – but the sahṛdaya or one who ‘has a heartfelt connection’ with existence. In this tradition, the higher yogin or homo religiosus has an empathic heart that beats in syntony and recognizes oneself in every manifestation of reality. He is the adhikārin,13 he who has proper skill in action; he is the siddhimān,14 who knows how to savour the generative quality of rasa. Aristocrats are qui rationem artis intelligunt, as Gnoli says, quoting Quintilian. Rasika or sahṛdaya are they who – we may say literally – ‘share their heart’ with things, because they discern the underlying vitality of everything.

On the other hand, nobility or greatness of soul in the Stoic and Platonic Western tradition, which we later find in Marcus Aurelius, is that vigilance [prosoché] that becomes ‘cosmic awareness’, detached from narrow individual vision and turned to a universal momentum for good. This attitude of the early Western philosophers gave rise in the 3rd century C.E. to the spiritual practice of the first monks for whom attention becomes that ‘guarding of the heart’ that reveals in each his divine vocation. According to non-dual Tantrism, attention plays the same prime role, but saṃsāra is not different from the liberated condition. In both, everywhere, Śiva shines and dances. He who is One says, “I’d like be many” [bahu syām], as told by one of the most ancient Upaniṣads (Chāndogya 6.2.3). Again, it is Śiva in the Svacchanda-tantra who is called Bahurūpa (of the many forms) for his versatility in being all things.

The awakening of the kuṇḍalinī, a highly important topos in yogic practice generally speaking as in today’s Kaśmīr, always occurs spontaneously, albeit prepared by two different paths: one, using vital breath, is known as prāṇa-kuṇḍalinī, or else training the strengthening of awareness, known as cit-kuṇḍalinī. But what launches the profound reawakening of vital energy – which in Kaśmīr coincides with awareness itself – in either of the two paths indifferently is conscious presence in the ordinary activities of everyday life. In every experience, without distinction, is saṃvit-rūpa āveśa; meaning that each experience is imbued in that single awareness that takes different forms. Thus, there is no demarcation between what is ‘spiritual’ and what is ‘ordinary’. It is merely a question of removing the obstacles that veil the living and conscious light from which all things existing are made.

At the base of this, crucial importance in applied yoga is played by the so-called krama-mudrā or bhairavī-mudrā that has many similarities with it. It is an inner disposition firmly anchored in a bodily centre and, at the same time, projected in an activity performed outside. This is an integrated and extremely advanced psycho-physical condition of non-dual yoga, to which Lakshmanjoo in his yoga teaching attributes great importance; even today it is still practised by the community that flourishes around the ashram he founded at Ishber Village. Having eliminated the fictitious barrier that separates the so-called inner world from the so-called outer, there remains only the vital connection between the two ‘worlds’: a diffused and all-pervasive awareness.

An example of this aptitude ‘straddling two worlds’ is found in the Vijñānabhairava-tantra (śl.51), which proposes the procedure for maintaining the attention of the inner dvādaśānta (any inner spot of the body) and, with the mind focused on that centre, devoting oneself to any activity of daily life with the same concentration [yathā tathā yatra tatra]. Thus, attention remains present, but simultaneously on both sides. Inner awareness acts, as it were, as a support for bodily dynamism externally, with a reciprocity that feeds both. In the words of Lakshmanjoo15 bhairavī-mudrā combines with the cakita-mudrā, the attitude of wonder, since dwelling between two worlds makes everything appear new, vivified, reawakened. Antar-lakṣyo bahir-dṛṣṭiḥ is as Abhinavagupta describes the bhairavī-mudrā: “turned inward but looking outward”16.

A yoga that strongly revalues ordinary experience, recognising in the latter the seeds of beauty and liberty that germinate fully in aesthetic and in truly spiritual experience, naturally lead to a non-yoga, i.e. a yoga that includes everything, a condition that Abhinavagupta indicates as anupāya: an experience of pure awareness all around, surpassing any kind of practice, rooting itself in the distinct sensation of being alive and in the awareness of being so. Personally, I have been able to verify, during my visit to Śrīnagar, to what extent this position is within the reach at least on principle, of every sincere practitioner and constitutes the natural and integrated destination of the yogic path. The sole fundamental element in yoga practice is training attention [avadhāna] to ever-deeper levels. And since awakening coincides with the authentic nature of reality, it is plausible that it may also reveal itself spontaneously through a simple act of recognition, an insight that irrupts without warning during our daily routine17.

The awakened condition may be described as svānanda (fulfilled happiness), a characteristic of the practitioner who reaches a high degree of qualification [adhikāra] or para-yogin18. It may equally be described as camatkāra, a psycho-physical aptitude characteristic of both rasāsvāda and brahmāsvāda. Camatkāra is that experience of the whole being that illuminates with awareness whatever appears inanimate [jaḍa]. Camatkāra is ajāḍyam, awareness of the luminous nature of all things that exist, that vivacity of the heart that makes whatever lives even more lively, that light of presence that throbs like the emotions, like life itself. Para-yoga is truly this amazing intensity.

The para-yogin consciously enjoys all this and knows how to discern the inexhaustible afflatus in every thought, in every word, in every āsana.

- Cf. R. Torella, Beauty, in V. Eltschinger et al. (eds.), Burlesque of the Philosophers: Indian and Buddhist Studies in Memory of Helmut Krasser, Hamburg Buddhist Studies Series, Projekt Verlag, Bochum-Freiburg 2023, pp. 763-87.

- R. Torella, Observations on yogipratyakṣa, in “Saṁskṛta-sādhutā: Goodness of Sanskrit. Studies in Honour of Professor Ashok N. Aklujkar. Edited by Chikafumi Watanabe, Michele Desmarais, and Yoshichika Honda, D. K. Printworld, New Delhi, India, 2012.”

- Cf. R. Torella, “Beauty” and R. Gnoli, 1968: 82.

- Locana on Dhvanyāloka III. 44. Quoted in R. Torella, “Beauty”.

- Utpaladeva in Śivastotrāvalī XVIII. 21b defines Śiva precisely as atisundara, ‘the supremely beautiful’. Quoted in R. Torella, “Beauty”.

- This condition of pure non-dual awareness goes in the same direction that R. K. C. Forman (Mysticism, Mind, Consciousness, pp.109-127; State University of New York Press, Albany 1999), on the subject of mystical experience, designates as knowledge by identity, an epistemological structure in which being and knowing coincide.

- Cf. M. Hulin, La mystique sauvage : aux antipodes de l’esprit, Presses universitaires de France, 1993. The author notes that Sanskrit has no term corresponding precisely to the adjective ‘beautiful’… Śubha, sundara, kalyāṇa include, according to the case, nuances such as ‘shininess’, ‘purity’, ‘good omen’, etc.

- R. Torella in the introduction to The Īśvarapratyabhijñākārikā of Utpaladeva with the Author’s Vṛtti. Introduction, Critical Edition and Annotated Translation, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi 2002. 2nd revised edition. 2021 (pp. XIV et seq..) quotes passages of Somānanda’s Śivadṛṣṭi (III 18ab) in which it is explicitly affirmed that the non-duality of Śiva, present and real in all phenomenal reality, is a direct manifestation of himself. The ekaśivatā is the sole essence of all things existing that also shine equally in his light. Things, animated by will and awareness (V, 4 – V 16, 37), are consequently not passive, but alive. Even though made of him, they have however their own specific autonomy.

- v. Spanda-kārikā 5: “nor does insentience exist” [na cāsti mūḍhabhāvo’pi].

- Cf. P. Hadot, Exercices spirituels et philosophie antique, Éditions Albin Michel, 2005: 119 et seq..

- Ibid (132 et seq.). Marcus Aurelius, Meditations III, 2.

- E. Hillesum, An interrupted life: the diaries of Etty Hillesum 1941-43, Washington, D.C., Washington Square 1985: 105.

- Abhinavabhāratī I, p. 280, R. Gnoli (1968: 63).

- Abhinavabhāratī I, p. 279. Ibid (57).

- Swami Lakshmanjoo, The Manual for Self-Realization. 112 Meditations of the Vijnana Bhairava Tantra, ed. by J. Hughes, Kashmir Shaiva Institute (Ishwar Ashram Trust), New Delhi 2016: 153.

- Tantrāloka 5. 80.

- As affirmed admirably by Utpaladeva (Śivastotrāvalī 18.13): ): Dwelling in the midst of the sea of supreme ambrosia, with my mind immersed solely in the worship of You, may I attend to all the common occupations of man, savouring the ineffable in every thing (trad. R.Torella, IPK p. XXXVI).

- As Abhinavagupta explains in Tantrāloka (cap.2) – and as, even today it is recognised in Kaśmīr (as explained to me by Pranāthji) – the hierarchy of yoga levels starts from the highest, the spontaneous means and non-means [anupāya], descending progressively to the means that use techniques [śāmbhava-upāya, cap.3, śākta-upaya, cap.4, āṇava-upāya, cap.5]. From a theoretical point of view, this ‘hierchical inversion’ gives everyone the possibility of instantaneous liberation.