Adrián Navigante

THE FREEDOM OF BEING IN-RELATION: ALAIN DANIÉLOU THROUGH THE VEIL OF TIME

This essay is a modified version of the introduction to the new Italian edition of Alain Daniélou’s Le Chemin du Labyrinthe. Ever since the publication of the first edition in 1981, these « memoirs » of Alain Daniélou have been taken mainly as a personal account of his life or as a testimony on a « bygone India » – outstripped by modernization and scholarship. Adrián Navigante shows that the scope of Le chemin du labyrinthe is much broader than its reception so far. If the reader takes the figure of the labyrinth seriously and follows the traces left by Daniélou, this seeming autobiography becomes a courageous intellectual adventure going far beyond India, in which thought is not detached from life, spirituality is not devoid of eroticism, and creativity is not opposed to knowledge but complementary to it.

Front cover of the third edition of Alain Daniélou’s Le Chemin du Labyrinthe (L’Age d’Homme, 2015).

Front cover of the third edition of Alain Daniélou’s Le Chemin du Labyrinthe (L’Age d’Homme, 2015).Human Adventure and Divine Play

Contrary to what readers may assume, Alain Daniélou’s Le Chemin du Labyrinthe [The Way to the Labyrinth] is not mere autobiography. Throughout the book, Alain Daniélou shows that subjectivity can be the mark of something broader and more significant. The text is an invitation to travel along a spirally coiled path in which different cultures, individual and collective myths, erotic and artistic encounters, religious and philosophical teachings lead him from the inherited constraints of his own milieu to a singular form of freedom. Not the freedom of absolute being, but the freedom of being in relation – with all the richness and beauty but also the risks and setbacks that relations sometimes imply. This is the figure of the Labyrinth. Daniélou invites us to follow the traces of his own path, face the paradoxes left behind and rethink, in a time of hypocritical conformism and world-wide constraints of all kinds, the possibility of our own freedom. Some of those paradoxes are challenging: A ‘Hindu’ born in Brittany whose deity of preference (Shiva) is not limited to the Indian subcontinent; an admirer of traditional Brahmanism who elevates Dravidian culture over the Vedic heritage; an anti-racist thinker who doesn’t hesitate to use the term ‘race’ when referring to ethnic or cultural groups in order to rescue their intrinsic value; a radical anti-colonialist who does not hide his taste for royal kingdoms; a denouncer of injustices who despises socialist thinking and rejects democracy; a passionate defender of ‘tradition’ (against the ‘myth of progress’) who is interested in modern science; a virulent anti-Christian who has an esteem for Jesus Christ; a Dionysian acolyte prone to nature religion who proclaims a Platonic conviction in the reality of mathematical structures. Precisely in facing such paradoxes, the reader may discover that the leading thread cutting across such tensions and polarities is the search for an unprejudiced point of view of reality.

It takes some effort, and surely a certain amount of courage, to enter Daniélou’s labyrinth. Readers are hardly familiar with such a territory. In our global culture, plurality degenerates into shallow fragmentation and compulsive unification seems the only criterion of consistency. Consumer society and its increasingly digitalized market are clear examples of the first trend, religious and political fundamentalisms stand for the second. Artists who sacrifice aesthetic production to cultural industry and scholars who reduce the world to their special fields do not escape the reductive polarization that ends up evacuating complex thinking processes (where paradoxes arise). An honest reading of Daniélou’s account implies leaving aside those prejudices to plunge into the narrative of a life in which many other voices are disclosed: voices of friends and enemies, but also of distant landscapes, forest spirits, Indian gods, and European ancestors. Daniélou’s narrative is at the same time the consolidation of a destiny, and since destiny surpasses by far the insignificance of a merely biological existence, Le Chemin du Labyrinthe can be taken as a message going far beyond Daniélou himself and the limitations of his own time.

“I have given myself completely to the present moment, throwing myself in the widest range of activities”, writes Daniélou in the prologue, “yet it seems clear to me now that destiny was waiting for me at every turn”1. For the individual, destiny is veiled by time. Yet, the labyrinth of a whole life contains (and in turn discloses) relations that are mysteriously concealed in the foldings of contingency. There is no translucid gaze through the veil of time; no human being can penetrate its depths. The task would be to create figures of displacement which may turn out to be instances of integration. The freedom of being in relation is a freedom in becoming.

In Le Chemin du Labyrinthe, Daniélou invites us to follow the traces of his own path, face the paradoxes left behind and rethink, in a time of hypocritical conformism and world-wide constraints of all kinds, the possibility of our own freedom.

At the beginning of his account, Daniélou writes that the spiral of life grants us moments in which very special (so far hidden) connections become possible. Time is intensified by active memories, chronology loses its monotonous density, our lives acquire another tinge. The dead return to us, the gods awaken and descend, desire wells up from the depths, old values are reenacted. Daniélou’s world is a bygone world, and yet it speaks to us. We enter other dimensions, time succession becomes relative, a much more complex logic prevails. Toward the end of Chapter 19, he declares that, in the face of a multiple and ungraspable reality, the task consists in understanding and realizing one’s own place in creation2. Many people tend to deny that complexity and take refuge in dogmatisms of any sort: a hypostasized spiritual tradition, a scientific truth turned into ideology, or a political idea attached to gregarious instincts. Some people, however, choose to deal with that complexity and work on a confluence of different but interconnected perspectives. The task is not to fix a certain form of knowledge, but to go through its twists and turns.

Daniélou’s testimony is profoundly subjective, but precisely because of that, it is no mere account of his individual life. Ultimately, it can be seen as a conscious effort to bring the human adventure to a point of confluence (in thinking and experience) with the divine play. Subjectivity has always been a mystery when we go beyond the banal sphere of the arbitrary and whimsical. Those who judge Daniélou by ‘objective standards’ are as wrong as those who take his personal testimony ‘literally’ and reduce the mystery of subjectivity to the banality of ‘an individual project’.

Itineraries and Passages

In his book Labyrinth-Studien, Karl Kerényi refers to the main problem in dealing with a figure like the labyrinth: the interpreter is faced with a problem that cannot be solved scientifically; it must be experienced and incorporated – rather like a poetic text3. The texture of Daniélou’s narration combines family history, travel experiences, memorable encounters, intellectual challenges, religious experiences, and philosophical intimations on specific situations as well as on fundamental questions of human life. This progression is not fortuitous. At the beginning of the book, we experience an individual talking about his immediate context (Brittany, France); toward the end, we are immersed in an elaborate worldview from which many aspects of Western culture (bourgeois education, religious dogmatism, political corruption, utopian idealism, colonizing anti-racism, etc.) are severely criticized and a counter-model is presented, not as a unity but as a vast array of complementary perspectives cleverly extracted from classical Indian philosophy. This passage from the individual and simple to the general and complex should not confuse us. At no moment does Daniélou portray himself as a guru, a prophet, or luminary of any kind. Quite on the contrary: his reflections intend to show possible ways of coming to terms with life. This is a typical human problem. Daniélou’s purpose is therefore far from that of divinizing human beings (i.e. placing them at the center of the labyrinth) or attaining spiritual enlightenment (since that would imply stepping out of the labyrinth). In Daniélou’s view, humans must be de-centered and re-integrated into another – broader – field of relations. The divine is not One but manifold, since it is open to experience4. The dignified place of humans in the universe coincides with a humble reduction of their ambitions.

Throughout Daniélou’s book, we will have access to some of the labyrinth’s paths and the manifold directions they disclose. By means of such a movement, Daniélou’s narrative inevitably triggers a reflection in the reader about life’s situations and choices – since, as readers, we are also engaged in the relations displayed throughout the book. We may mention three examples (among many others). The first example concerns the experience of the sacred. Daniélou has a significant experience as a child in a wood of Brittany, where he senses a divine presence. This presence will reappear and consolidate itself during his long sojourn in India (where he was reeducated and initiated into a living tradition) and further after his return to the West (where he attempted to retrieve the lost thread of such power in the ancient traditions of Europe). It is on the basis of that strongly religious and deeply embodied connection that Daniélou attempts to establish a link between the Celtic god Cernunnos, the Hindu deity Shiva and a Greco-Thracian version of Dionysus – all three of them forces of nature essentially connected to sexual power. The second example refers to the attitude toward ‘the other’. On the occasion of his first voyage to Algeria5, the young Daniélou plunges into the inner life of foreign cultures without any pretension of explaining them by translating such experiences into the theoretical vocabulary of the West. His notes on Arabic music from that early period anticipate in many ways both the titanic work he carried out on Indian classical music during his long stay in India as well as the ambitious project at the International Institute of Comparative Music Studies in Berlin, upon his return to Europe, to show the value of traditional music throughout the world. The third example relates to his critique of Eurocentrism. Daniélou’s account of one of his first visits to India contains a critique of what today would be termed (sometimes equivocally) ‘white power’. This will be a recurrent topic in the book with different variations and a certain escalation as the narration progresses. It begins anecdotally, in Chapter 5, when Daniélou refers to the Indians travelling like cattle (from Peshawar to Calcutta) in a third-class carriage, while Europeans occupied the luxurious first-class compartments; it goes on with a denunciation of British lords in north Calcutta whose hunting targets included indigenous groups along the Bhagirathi River6. As the narration progresses, Daniélou broadens the scope of his critique and thematizes the oppression suffered by ancient Dravidian populations at the hands of Indo-Aryan groups – related to Vedic culture – to finally put forward a general theory, in Chapter 19, of the predatory nature of Aryan populations: Achaeans, Dorians, Celts, Germans, Russians, etc., all of them ultimately destined to self-destruction after their own force of expansion has reached a territorial limit7.

Daniélou’s testimony is profoundly subjective, but precisely because of that, it is no mere account of his individual life. Ultimately, it can be seen as a conscious effort to bring the human adventure to a point of confluence with the divine play.

Each one of Daniélou’s reflections is related to concrete experiences (from the most ordinary to the most significant ones) in which he takes a certain position. The three examples mentioned above may become quite challenging for the reader, since they refer to problems that are at the center of our cultural agenda today: the existential crisis due to the isolation of human beings in an increasingly nihilistic setting, their inability to understand and deal with differences, and the question of domination and oppression (especially in the name of civilization or progress). Do we have a real connection with the sacred apart from the worn-out dogmas handed down to us and the poor surrogates of consumer society? When we deal with another culture, why do we tend to immediately impose our own categories and simplify the matter instead of learning from it? Does the affirmation of an identity necessarily imply a violent delimitation of “the other”? These are some of the questions triggered by Daniélou’s account, and the reason why taking Le Chemin du Labyrinthe as a mere autobiography does not do justice to the book.

The above-mentioned examples show that behind some of Daniélou’s critical remarks there is a subtle consideration of a problem that far surpasses the immediate account we read. The reader of Le Chemin du Labyrinthe will surely enjoy the entertaining dimension of Daniélou’s narrative: his conflict-laden relations with avant-garde artists in Paris, his experience with Rabindranath Tagore in Shantiniketan, his encounter with Iranian native warriors in the desert of Baluchistan, etc. However, this aspect does not exhaust the potential of its content. It is also possible to gain access to deeper layers of the text, where the narrative becomes a cartography of less personal – and more significant – relations. Those layers become clearly manifest and even dominant in Chapter 8, where Daniélou refers to his life in India8. At that point, the external voyage ceases and another movement begins, that of a reeducation and a transformation, and a qualitative expansion of relations. Daniélou’s ‘passage to India’ is also the possibility of a bridge to a Europe prior to the ‘exile of the gods’. This movement intends to retrieve all possible lessons of wisdom related to a ‘religion of Nature’9, the religion of the chthonic gods who did not suffer the ravages of internal dissection – unlike the Olympic ones. It is also a potential opening to many other cultures of our present time which still preserve that link to the sacred.

Indic-Italic Mythologies

Many creative thinkers are controversial to the point of being marginalized by the cultural consensus of their time, and Alain Daniélou is no exception. In Le Chemin du Labyrinthe, the reader will find many interesting entrance doors to his thought, not only to his musicological work, which is unanimously recognized even today, but also to his views on Indian society, history, philosophy, and religion, which were progressively contested with the development of South Asian scholarship and impossible to reconcile with the Neo-Vedantic trend that was increasingly adapted to the spiritual needs of the modern West. In Chapter 16, Daniélou himself defines the passage from the well delimited field of musicology to a broader approach to Indian culture as “an arduous task”10, since he knows very well that, in his case, the difference of attitudes, methods and contents with regard to mainstream scholarship is considerable. From a scholarly point of view, the affirmation that the Pashupati seal of the Indus Valley civilization (which dates back to the third millennium BCE) represents the Hindu god Shiva of the classical and medieval period (from the middle Upanishads and the epics to the Mahapuranas), or the thesis that Dravidian populations were cast out of their territories by Aryan invaders in the second millennium BCE, or the hypothesis of an esoteric Shaivite substrate circulating not only among errant ascetics on the margins of society but also among Hindu orthodox scholars abiding by Dharmashastric rules may be seen more as the product of imagination than of scientific work.

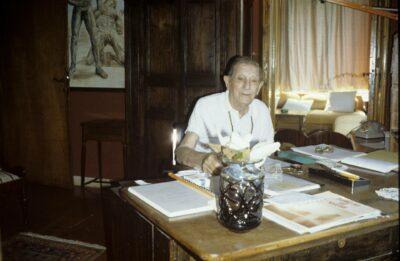

Alain Daniélou at the Labyrinth

Alain Daniélou at the Labyrinth(photo by Jacques Cloarec, 1989, archive of the Alain Daniélou Foundation).

In reading Le Chemin du Labyrinthe, the reader will see that Daniélou makes a drastic distinction between the mechanisms of knowledge legitimation in Western scholarship and in the traditional Hindu milieu of Benares, where he spent sixteen years of his life. In Western scholarship, the validity of knowledge depends on objectivity criteria, mainly of the type of research on written sources; in the traditional Hindu milieu, knowledge results from oral teachings and their multi-perspectivist dynamics. Such a modality of knowledge transmission, which is not focused on objectifying and delimiting contents from a purportedly neutral position, must necessarily include thinking and discursive patterns shoved aside or rejected by science. One of the central questions of this dispute relates to mythology. For Daniélou, myth is not a fictional narrative but a codified testimony of interaction between humans and other levels of being; artistic expression is not an arbitrary act of a single subject but a sacred activity extending to a whole community; intellectual history is not only configured through textual analysis but through iconographical production, ritual, musical and dance performance as well as through non-human agency (revelations of gods, irruptions of demons, or interventions of mythic beings). This is what he learned in traditional Hindu milieus. All the instances of interaction Daniélou refers to, which require different intellectual procedures as well as artistic and religious performances, contribute to the ultimately unfathomable rhythm of being, and his scansion embraces all levels. In the last chapter of the book, he refers to himself as a hard worker who cannot bear to be idle: “Once I have mastered a subject or a technique, I feel no desire to exploit it or turn it to my advantage, and immediately I want to go on to something new”11. This permanent shift of domains, normally regarded as loss of focus or lack of solidity, turns out to be an effective antidote against the alienation of both blinkered specialists (well-established in clearly delimited research domains) and dogmatic preachers (excessively prone to metaphysically revealed truths). It is at this point that the main paradox of Le Chemin du Labyrinthe becomes prominent: when Daniélou says that his task is to bear witness to the true message of India for the West, he does not mean that he bears the truth of that message. In fact, what is called ‘truth’ cannot be reduced to a metaphysical principle (too abstract to deserve that name) or to an empirical fact (too raw without the corresponding interpretation). It is, quite the contrary, a complex existential procedure. Daniélou did not extract any literal truth from India to be mechanically applied to the West (as is the case of vulgar metaphysicians and pseudo-gurus). He has made the lesson of India his own existential truth and developed it further, with a controversially creative spirit, in every one of the contexts that destiny unfolded to him. His existential procedure has therefore cultural effects, and it is the construction of a myth that matters – once again, not in the sense of a fictional story, but rather of a living truth that fills the person’s existence with meaning and permeates his/her whole field of relations. The architectural structure of his myth is the Labyrinth, but he is not the mythmaker. He is rather a channel or a link in the transmission of that message. Daniélou follows traces before him and leaves traces behind him; he varies the different figures to (re-)chart the labyrinth according to his time. This is the main procedure in his narrative.

All the instances of interaction Daniélou refers to, which require different intellectual procedures as well as artistic and religious performances, contribute to the ultimately unfathomable rhythm of being, and his scansion embraces all levels.

We can give two examples of Daniélou’s procedure, which show how playful his own passion for knowledge has always been and how important paradoxes are in his own dynamics of thinking. The first example concerns his relationship with the god Shiva. In Chapter 8, Daniélou recounts his life in the traditional milieu of Benares, where he stayed between 1937 and 195312. In the back of the palace where he lived with his partner, Raymond Burnier, he found a sanctuary devoted to Shiva and hired a Brahmin to perform the corresponding rites. Soon afterward he met the local Shaivite devotees and scholars, with whom he embarked on assiduous studies and practices (including Indian classical music) to end up being initiated by order of one of the most important spiritual leaders of northern India, Swami Karpatri. He opened his palace’s doors to Shaivite ascetics who would regularly stay at his place. He took lessons with a left-hand path Tantric practitioner and got progressively imbued in the religious atmosphere of Shiva’s luminous city, Kashi, far away from Western habits of thought. For some people these are exotic experiences and maybe cultural achievements; for Daniélou, the whole story was mainly an increasing connection with the divine. The divine, as he says in Chapter 21, paraphrasing the first verses of the Īśa-Upaniṣad, “dwells everywhere”13, and he himself became its abode. When Daniélou speaks about Shiva, he refers to the Lord of all creatures – not only humans but also animals and trees. His god is no abstract metaphysical principle. The minimal degree of manifestation, symbolized by the lingam, refers to the most intense concentration of life – hence Daniélou’s insistence on the link between eroticism and divine energy. Such affirmation of the forces of Nature permeating and transcending the human person leads him beyond his immediate context, back to his early experience of the sacred in Brittany. It pierces the veil of time: “Here was the god I had intuitively sought in my childhood”14, he writes, once again sensing the emergence of destiny in the weaves of contingency. Daniélou’s pre-Aryan Shiva, which he encountered in Benares, turns out to be the Proto-Celtic god Cernunnos coming back to him in a later period of his life, but this is not all. After his return to Europe, Daniélou found in the figure of the Dionysus another variation of that Protean spout of life and overflowing energy embodied in Cernunnos and Shiva, an energy prior to any moral restraint, religious norm, economic calculation, or social mechanism. The main theses of books like Deification of Eroticism, Shiva and Dionysus or The Phallus are certainly the result of research, but mainly they are a cross-cultural and analogical elaboration of his own experience of the divine. This aspect explains the increasingly contested amplification in his work: it is ultimately Daniélou’s own theistic-animist ethos and his ‘return to paganism’15, confronted by the real presences of his destiny, that sets the parameters of his interpretation.

The second example of Daniélou’s procedure relates to the place he chose to spend the last period of his life, the Labyrinth at Zagarolo. Having spent more than twenty years in India, imbued as he was with the different traditional and local aspects of the Asian subcontinent, it was difficult for him to readapt to Europe. As he recounts in Chapter 13, he felt particularly uncomfortable in France, and the rest of Europe didn’t fulfill any expectation of his16. Italy was clearly the only country in which he felt he could live. However, the search for a concrete location in that land was not easy. Rome, which he visited in many occasions after his return to Europe, seemed to him increasingly ravaged by dishonest politicians and rapacious bourgeois; Venice, a significant episode (mainly due to his musicological activities at the Cini Foundation) to which he devotes the entire chapter 18, remained a hostile setting for him despite its cultural value. Neither Naples nor Amalfi, two places he fancied very much, could convince him to drop anchor. Instead, it was in a small and apparently insignificant town of the Roman province, Zagarolo, where he found his place. In Chapter 13, Daniélou describes Zagarolo as a magical place “where the forces of heaven and earth meet and one feels the presence of the gods”17. For Daniélou, Zagarolo has different layers, not only as a natural setting but also as a cultural complex with an unknown story. He connects the hill of the Labyrinth (the residential area in Zagarolo where he was offered a house) and its Etruscan remains with the religious complex of the great goddess from Præneste, Fortuna Primigenia, and points to two significant historical moments: the first dating back to ancient Rome under the emperor Hadrian, when the temple was enlarged and a palace was built at the foot of the hill; the second taking place during the Renaissance under Francesco Colonna, who built a palace over the ruins of the sanctuary in order to protect it. But for Daniélou the parallel does not end there. In the same way in which Hadrian gathered wise men to keep the secrets of the ancient Egypian religion alive, Francesco Colonna gathered the first humanists seeking ancient wisdom in “his other palace located at Zagarolo”18. This connection between Palestrina and Zagarolo as sacred focal points of the Italian peninsula goes hand in hand with the centrality Daniélou ascribes to Francesco Colonna in the cultural production of the Renaissance. But who exactly is Francesco Colonna? Certainly not the Venetian Dominican priest and reputed author of the remarkable allegorical tale Hypnerotomachia Poliphili [Poliphilio’s Strife of Love in a Dream]. Danielou purposely moves away from the mainstream reception of Renaissance culture. In his attempt to highlight the ancient wisdom around Præneste and reconfigure the cultural geography of the fifteenth century, Daniélou shifts the focus from Franceso Colonna of Venice (1433-1527) to Francesco Colonna of Palestrina (c.1453-1538), member of the Roman Academy of Pomponius Laetus. As in the case of his interpretation of Indian sources, Daniélou’s reading of Renaissance humanism is decidedly heterodox, but certainly not a mere invention. In the mid 1960s, Italian art critic Maurizio Calvesi published an essay in the review Europa Letteraria entitled ‘Identificato l’autore del Polifilo’, in which he identifies Francesco Colonna of Palestrina as the author of the Hypnerotomachia. His further research would lead to a book published in 1980, Il Sogno di Polifilio Prenestino19. In that book, Calvesi intends to reverse a dominant trend dating back to the Venetian man of letters Apostolo Zeno, who – as early as in 1512 – attributed the authorship of the Hypnerotomachia to Francesco Colonna the Dominican monk. Maurizio Calvesi contends that the new Virgil and Cicero, praised in an epigram of the XV century presumably written by the Bolognese aristocrat Raffaele Zovensoni, is in fact Francesco Colonna of Palestrina.

Daniélou’s shift of focus from Venice to Præneste is closely related to his readings of Maurizio Calvesi through the mediation of the Italian art historian Emanuela Krezulesco Quaranta, whose book Les Jardins du Songe (1976) inspired not only Daniélou’s variation of the Zagarolo myth in Le Chemin du Labyrinthe but also one of his most significant tales of the labyrinth (published in 1991), Le Jardin des Songes, in which we see the same humanist circle at work for a restitution of a civilization that has lost its course. Daniélou also plays with the idea that in the humanist activities of Latium there circulated a form of ancient wisdom transmitted within esoteric Etruscan circles of Tusculum which probably go back to the times of the Trojan war. In clear analogy to the Puranic literature of India, his narration fuses historical facts with mythological themes. This intentional twist of register does not intend to contort facts in the name of fiction but to account for paradoxical levels of reality and experience that demand a different approach – where the delimitation of ‘fact’ and ‘fiction’ does not hold. This is also the main subject of Daniélou’s Les contes du Labyrinthe, a book that Daniélou refused to define as fictional work20.

Through the Veil of Time and Toward a New Light

There are few authors as difficult to classify as Alain Daniélou. This difficulty goes hand in hand with the readers’ creation of pre-texts to justify their own approach to his thought. A man without academic credentials, he cultivated a principle of uncertainty about the location of his own activities and thoughts: musician, painter, dancer, writer, translator, Indologist, philosopher, Shaivite initiate, etc. To highlight the paradoxical even more, Daniélou was a playful and subversive author who nevertheless expressed reactionary ideas that shocked forward-looking intellectuals. Most of the problems of the modern West are for him the result of maladjusted petit bourgeois (among whom he counts figures from Theodor Adorno to Jean-Paul Sartre) who spent their lives daydreaming instead of learning. In his eyes, the caste system in India deserves to be examined in depth instead of being portrayed as an abomination by people who ignore that culture. Quite on the contrary, egalitarianism is for him a selective and hypocritical ideology contributing to the expansion of colonial power. The modern forms of Hinduism that have conquered the West, epitomized by well-known authors such as Vivekananda, Aurobindo, Shivananda and Ramana Maharshi, have no value whatsoever – or rather, they have a negative value. Their doctrines appear to him as a generalization of one single system (Vedanta) to the detriment of a non-dogmatic philosophical perspectivism (that of classical Hinduism). In addition, the presence of different elements of Western – scientific or esoteric – doctrines in some of their conceptions render them even less reliable as a real alternative to the Western cultural production. When it comes to criticizing Gandhi and Nehru for the ‘Westernization’ of India, Daniélou combines historical and political arguments with very personal – and therefore intellectually sterile – attacks. He mistrusts esoteric authors and milieus, which leads him to become excessively (and unfairly) judgmental with authors like Mircea Eliade, artists like Nicolas Roerich or humanist circles like Eranos at Ascona. Apart from that inflexible attitude, he fails to recognize that there is as much (Western and modern) ‘esoteric invention’ in René Guénon (to whom he pays homage) as in Madame Blavatsky (whom he rejects altogether). These remarks intend to say that, in the pages of Daniélou’s account of his life, we are not spared the subjectivity of the author in the narrowest and most outspoken sense of the word.

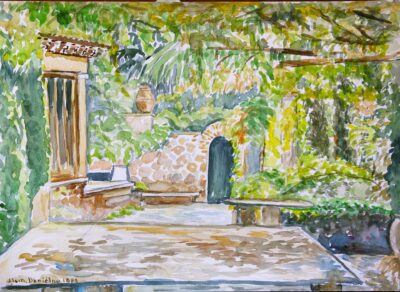

One of Alain Daniélou’s water-colours depicting the terrace of the Labyrinth’s main house (photo by Giorgio Pace, 2022).

One of Alain Daniélou’s water-colours depicting the terrace of the Labyrinth’s main house (photo by Giorgio Pace, 2022).Those instances are nevertheless part of the richness and sincerity of Daniélou’s own account, and the reader is compelled to find inroads to ideological turning points. Because he does not stoop to please the right-minded, he forces the reader to pick up and reshape the traces of his labyrinth – as if he himself were asking the reader to perfect his own attempt. Le Chemin du Labyrinthe is no mere accumulation of anecdotes, reflections, and judgements. Its guiding thread is the testimony of an adventurous journey leading to the reeducation of a person and his reconnection with Life. The opening epigraph (attributed to Aristotle) reads: “the rightness of the path you have chosen will be measured by your happiness”21. This is not (only) a warning against excessive intellectualism, inflexible dogmatism and illusory (or delusional) utopianism, but the expression of an outright conviction: humans are happy if they get the best out of life – which is not always possible, since humans, regardless of the objective circumstances, are masters of self-boycott. This eudemonistic maxim anticipates the link between the contingencies of the individual’s adventures and the deep structures of his fate. It is displayed (with the manifold tensions contained in a human life) throughout the book, but radically transformed in the closing remark: “The only fear I have is that I might not have given enough before I pass”22.

Daniélou’s subtle feeling of apprehension in affirming an accomplished life can be seen as the recognition that happiness has a reverse side – without which it implodes into an empty hedonism. The reverse-side of ‘receiving from life’ consists in ‘sharing and giving’, that is, in de-centering oneself. In this way, the individual passes from the limited expansion of a limited self to the cosmic threads of an ever-expanding labyrinth, where relations of another kind may arise – and even blossom. No wonder that Daniélou’s rather irreverent translation of the first verses of Īśa-Upaniṣad does not focus on the supreme Ruler of the world but on the distribution of beings in it, and what that logic implies: “In a world where everything changes, where nothing is permanent, the divine dwells everywhere: in flowers, birds, animals, forest vegetation and human beings. Enjoy fully what the gods leave for you and never covet what belongs to others”23. The freedom of being is paradoxical, because it is freedom in becoming, that is, in permanent relation and never free from contingency. And the divine is also part of it. This is perhaps the most original aspect of the – both Pagan and polytheistic – message that the readers of Le Chemin du Labyrinthe should pick up and re-think in the light (or rather shadows) of the present time.

- Alain Daniélou, Le Chemin du Labyrinthe, Lausanne 2015, p. 10. All quotations are taken from the French version of 2015 (the third expanded edition of the text), and all translations are mine.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Le Chemin du Labyrinthe, p. 320.

- Karl Kerényi. Labyrinth-Studien: Labyrinthos als Linienreflex einer mythologischen Idee, Zürich 1950, p. 11.

- Daniélou’s ‘polytheism’ is neither a mere provocation against the dominance of dual aspect monism in the Western reception of Hinduism nor a short-sighted affirmation of the theological reality of Hindu doctrines that overlooks the metaphysical radicalness of concepts like the impersonal absolute [parabrahman], or the Supreme reality [anuttara]. It is a very logical way of doing justice to every level of religious performance across the Indian Subcontinent, but even more important: it is an antidote to the ideological operation of transforming a specific philosophical school (Advaita Vedanta) into a universal doctrine – dangerously close to the exclusivity of monotheism –, as well as an attempt to bring back the dimension of multiple experience that opens many of the religious phenomena in India to other cultures of the world (as Daniélou emphasized in his later writings).

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Le Chemin du Labyrinthe, Chapter 4, pp. 76-77.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Le Chemin du Labyrinthe, pp. 90-92.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Le Chemin du Labyrinthe, p. 301. The theory of an ‘Aryan invasion’ marking the passage from the Indus-Valley civilization to Vedic culture has been contested by many authors, and Daniélou’s equation of Indo-Aryan and predatory invaders is too general, homogeneous, and hyperbolic to be considered ‘scientifically valid’. The main point is not scientific validity, though. Apart from the fact that the contrary has not been proven, and that the scientific standards of the Humanities are quite different from those of natural sciences, such aspects of Daniélou’s thought are relevant for an understanding of how he articulated his own position and constructed his own philosophy confronted with problems of utmost relevance such as colonialism, imperialist wars and discrimination of all types based on ethnocentric standards.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Le Chemin du Labyrinthe, Chapter 8 : La vie en Inde, pp. 127-158.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Shiva et Dionysos, Paris 1979, p. 20.

- Alain Daniélou, Le Chemin du Labyrinthe, p. 260: “After ten years of successful efforts, the great musicians of South Asia had gained recognition and had already been integrated in the international music scene. That was an essential first step before passing on to the more arduous task of rendering other aspects of Indian culture accessible, such as its philosophy, its religion and its social structures”.

- Alain Daniélou, Le Chemin du Labyrinthe, Chapter 20, p. 321.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Le Chemin du Labyrinthe, pp. 127-158.

- Alain Daniélou, Le Chemin du Labyrinthe, p. 329.

- Alain Daniélou, Le Chemin du Labyrinthe, Chapter 8, p. 143.

- Cf. the section in Chapter 21 entitled “Return to Paganism” (Le Chemin du Labyrinthe, pp. 343-344). The ideas that are succinctly expressed in those paragraphs reappear in other books, mainly in Shiva et Dionysos, where Daniélou’s paganism is developed into a program for the future.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Le Chemin du Labyrinthe, pp. 215-217.

- Alain Daniélou, Le Chemin du Labyrinthe, p. 226.

- Alain Daniélou, Le Chemin du Labyrinthe, p. 228.

- Maurizio Calvesi, Il sogno di Polifilio Prenestino, Roma 1980. The book expands some central ideas on the subject that the author had already expressed in a previous article published in 1965.

- “I have merely tried to consider history on a level different from that of appearances, and I am convinced that such vision corresponds to an invisible but ever-present reality” (Alain Daniélou, Les contes du Labyrinthe, p. 9).

- In the form quoted by Daniélou, this passage is not found in the whole Aristotelian corpus, but that should not surprise the reader, since Daniélou often quoted by heart or resorted to indirect sources without much attention to philologically relevant distinctions – especially in dealing with Western material. The psychoanalytic sources quoted in his last publication, Le Phallus (1993), are a clear example of this aspect.

- Alain Daniélou, Le Chemin du Labyrinthe, p.325.

- Alain Daniélou, Le Chemin du Labyrinthe, p. 329.