- » Interview with Alain Daniélou, PRE-ARYAN SHAIVITE CULTURE: A TRADITION TO BE RECOVERED

- » Sunandan Chowdhury, East and West in Rabindranath Tagore

- » Christof Zotter, BĀBĀ KĪNĀRĀM AND THE AGHORĪ TRADITION IN NORTHERN INDIA

- » Basile Goudabla Kligueh, Vodu and Nature: The Vodu Adept’s Communion with Nature

- » Fabrizia Baldissera, Notes on Maṇḍalas, cakras, and the resilience of the circular icon in contemporary Indian imagery

Fabrizia Baldissera

Professor for Sanskrit Language and Literature, University of Florence, Italy

All the images in this article are by Stephen Roach

Fabrizia Baldissera, professor of Sanskrit language and literature, presents an inspiring summary of a scholarly and artistic project she conducted with photographer Stephen Roach, both as Alain Daniélou Foundation grantees, on the resiliency of mandalic shapes in different aspects of Indian culture.

I was really interested in things Indian from a very early age, and my first exposure was a long trip there in 1969, when I travelled overland to North India and Nepal.

Observations leading to the idea of a book, however, occurred first to Stephen in 1994, on one of the voyages in India we made together. His first relevant photographs were taken at that time, and again in 1995, 2004, 2011 and 2016. They come from sojourns in Maharashtra, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Kerala.

For years in our Indian travels Stephen and I had marvelled at the wealth of Mandala-like shapes found in the ordinariness of the everyday.

Stephen, with his artist’s interest in the contemporary, was struck by the endless variety of these representations, and their use in a multiplicity of disparate ways. I kept being reminded of their ancient function, both in ritual as well as in geopolitical terms, and wondered at the nuanced feelings these contemporary images might evoke in the minds/hearts of their Indian makers and onlookers. Except for some cases, as in the special golam or raṅguli drawn by women on the floor in front of houses for auspicious reasons, or to mark a particular occasion, the configurations we noticed did not convey a religious meaning. They served entirely different purposes, in fact. Yet the very abundance of these images pointed to an underlying consistency of intent. I felt that their profane use in every street we passed was reinforced by the fact that Mandalas were still so present in Indian ritual life, at all levels of society. We started to work together on the idea of a book where images and words would mirror each other, looking for this elusive metaphor, the circle, image of the cosmos and of the wheel of time, as well as of innumerable natural forms.

Circular images have been frequently employed also in many other countries and cultures. Plato, for instance, believed the sphere was the perfect shape, and decreed that not only the planets, but also their orbits had to be round…but nowhere have we seen such a preponderance of round images, and of wheels, as in India. The Indian flag itself carries the wheel, that may be interpreted either as the spinning wheel of Gandhi, symbol of Indian independence, or, in a more traditional way, as the might of a great sovereign power. The contemporary Indian fascination with these images in everyday life is rooted in ancient ideas, and illuminates a particular poetics that the eye of the photographer reveals in its incessant movement. The circular motion acts in unison with the expansion and contraction generated by outgoing and ingoing breath. It goes from the minutest centre of energy, the bindu, ‘drop’, where the universe contracts to a mere point, to the endless variety assumed by all forms of life in the deployment of the cosmos. It opens and shuts the eyes of deities and humans alike. The photographs follow the labyrinth of these configurations in the stark Indian light of a sunny day, or under the glow of a naked bulb at night. And ancient and new images keep reinforcing and echoing each other.

As a visual artifact, the Mandala, just like a similar image, the cakra, ‘wheel’, is used extensively as a graphic symbol and is found so often in Indian life that it has become ubiquitous, almost non-descript, and in a sense, therefore, people perceive it subliminally, rather than consciously acknowledging its presence. In recent years, in fact, I have asked a number of people in India if they had considered the overwhelming presence of Mandala configurations in contemporary Indian visual culture and everyone I asked found the question odd. Later, however, several of our Indian friends wrote back to me, or told me that since Stephen or I had spoken to them about it, they had actually started to notice the many instances of contemporary, non-ritual and non-religious Mandala images laying all around them.

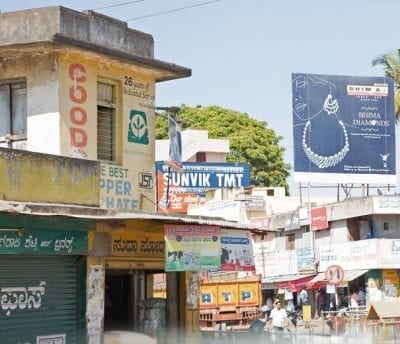

We had initially observed that in India, in the past thirty odds years, both decorations and advertising kept making a large use of these images. Only quite recently, however, we started to see new trends in those fields, that point in the direction of a different visual approach, similar to what can be found in western urban environments. Two Indian friends interested in contemporary art, as well as in graphics and printing, one from Maharashtra, the other from Kerala, in recent conversations maintained that lately some of the best Indian designers of advertisement had started using new shapes, different geometrical forms, rather than the customary circles and spheres. We have also seen that in the last fifteen to twenty years, photography and digital technology has replaced most painting in publicity and advertising.

As for decorations and adornments: the love of adornment has continued unabated for centuries…Now, in contemporary India, only gold, diamonds and pearls are considered real jewels. The great favourites are pearls, both as actual jewels, perfect in their roundness, and as a metaphor of excellence. Whereas in the west we speak of excellence as ‘flower’, like in ‘anthology’, ‘the choice of [the best]flowers’, in India excellent poetical verses were called muktakas, ‘pearls’, and the good writer was then supposed to string them together in another circular ornament, a necklace or a garland, mālā.

In spite of the new trends in ads which have gained space especially on large high-rise buildings and on the roads leading from an airport to a town’s centre, one can still see a profusion of Mandala-like shapes, and not only in ancient religious or political representations preserved in temples and palaces. They are actual images used in road signs, publicity, patterns drawn on clothing and materials, jewelry, decorative architectural elements on pavements, walls and floors, political billboards and symbols, items used for eating or to decorate tables, contemporary works of art, and in innumerable other settings. This ordinary, everyday use follows highly conceptual religious and political thought as well as being the simple representation of natural elements found sometimes right on one’s doorstep.

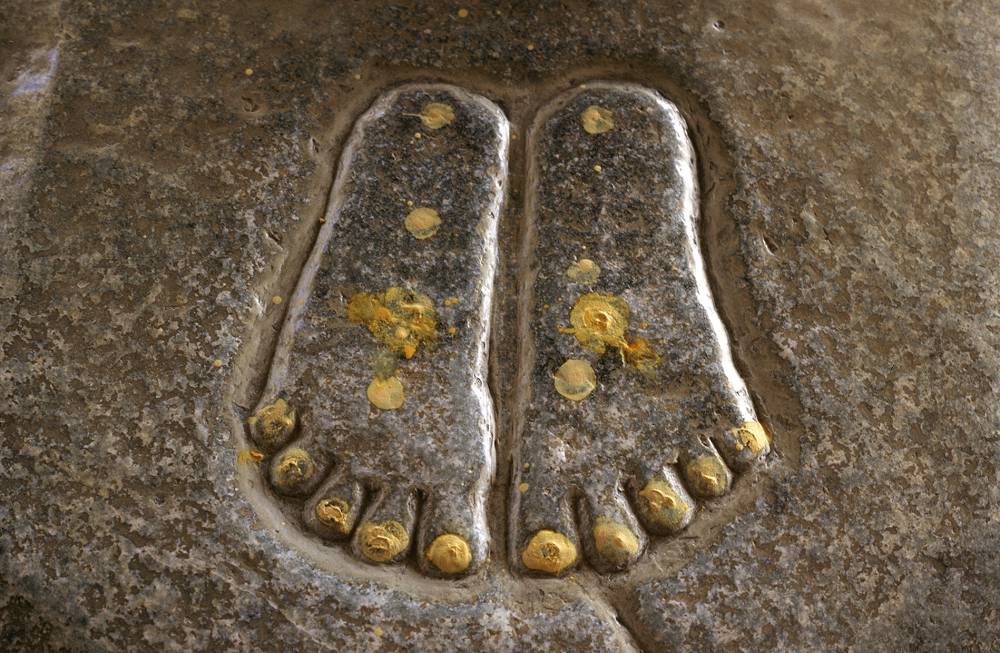

The most widely encountered image of the Mandala is a circle, but it can also be represented by a bindu, a small dot, sometimes made of yellow sandal paste, but more usually of red powder, often drawn for auspicious reasons. At particular times it may also be put on appliances, like on the electrical power boxes of private apartment blocks, for protection.

In this figurative all round consistency one finds an intriguing blend that constantly reiterates deep-rooted structures in Indian thought, as for instance the idea of saṃsāra1, the constantly revolving cycle of birth, death and rebirth, sometimes represented by the halo of flames circling the icon of Śiva Nāṭarāja, Lord of Dance, or symbolized by the eye-blink of a deity. And the decoration women put between their brows, a dot, or a tattoo with a half moon and a circle, alludes to eye of wisdom, but is also an allurement.

These images then flow into the constantly changing contemporary visual world, which is increasingly man made and theoretically non-religious and non-political, but where religion, politics and new economy meet in an uncanny covenant.

The importance of the Mandala in its twin religious and political facets was stated in a simple way by André Padoux when in one of his studies on Tantra he wrote of the monarch and of his relation to the kingdom, that was conceived spatially and politically as a maṇḍala:

‘The maṇḍala is a space in which the deities are placed, and where they can exert their power’2.

Ritually, the relevant fact is that the deities are placed there by means of Mantras, the secret syllables that empower the maṇḍala and make it fit to receive the deities. This requires the presence of a specialized ritualist, who knows the appropriate Mantra for the occasion, and can utter it correctly, so as to attain the desired result. The mandalic configuration applies equally to the sacred diagram, at times called yantra, in which the deities are invited during a rite, or to a large pilgrimage circuit that touches different temples or sacred images located in a particular geographical area. On a more worldly level, it also applies to the political conceptions of the oldest extant Indian treatise on governance, economics and politics intended for the instruction of a king, the Arthaśāstra. Its period of composition dates from the middle of the first century BCE to the third century CE, and its views are the same as those of several tantric traditions. All of these indeed agree in considering a realm as a maṇḍala, a ritually determined space, protected by deities.

In ancient South East Asia, the city-states with their surrounding territory were called maṇḍala, and even today a central region of Myanmar with its presiding city is still called Mandalay.

In some cases, when there is a group of deities that are worshipped together as a set, their sanctuaries may have been arranged in a maṇḍala configuration in a particular area, as those around the temple of Vindhyavāsinī near Varanasi, so that the pilgrims visit them in a certain order. In the words of Padoux, «a circuit of shrines delimits a Vindyakṣetra, the holy space that is formed by the Vindhya mountains, and reproduces on the territory the triangle that is the symbol of the goddess»3. The same occurs for the somewhat irregularly shaped maṇḍala formed by the nine sanctuaries of the Navadurgas in Bhaktapur, the ancient city of the Newars in Nepal. When I attended the Navadurgas festival a couple of years ago, I followed devotees who moved around the city-maṇḍala starting each dawn in one of the nine portions in which it is ritually divided.

The maṇḍala is a space in which the deities are placed, and where they can exert their power

In more remote times, towards the end of the second millennium BCE, the term maṇḍala (here taken in its first meaning of ‘circle’) qualified the subdivisions of the most ancient vedic scripture, the Ṛgveda. As a geometrical and visual configuration, the Mandala is at once spatial, political, symbolical and religious. In spatial terms, it usually4 indicates a circle or a sphere, and one of its particular uses is in the vastumaṇḍala, the diagram employed for building temples and palaces, and also to inscribe figures for a sculptural program5. In politico-geographical terms, it qualifies both the spatial extension and the sphere of influence of a particular kingdom, as a cosmological symbol it may be a representation of the planets and of the entire universe, as well as its integration by human beings. In religious contexts, after its first use in the Ṛgveda, the term maṇḍala was also used to qualify the different branches of particular tantric schools, and practices of these schools.

A similar image, the round cakra, ‘wheel’ and ‘discus’, appeared first, in the Vedas, as the weapon of Indra, king of the gods, and later as that of Viṣṇu. An early depiction of this wheel in vaiśṇava context is on a silver coin form the first century BCE. Later, in early Gupta times, there was sometimes an attendant figure, a wheel-man, cakrapuruṣa, or, around the fifth century CE, a weapon-man, āyudhapuruṣa, like in cave 6 at Udayagiri, and around 578 CE in the caves of Badami. Occasionally, a wheel is found on top of a lotus flower6.

In later religious (and alchemical) developments, the cakras, conceived in motion, are seen as centres of energy within the human body, in Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism alike. In a tantric context dhyāna, ‘meditation [as the representation of the deity]’, takes place within one’s body. The tantric adept visualizes the deities present in the six cakras, ‘wheels’, located in his7 own body, that “often form a cosmic maṇḍala”8. Through his meditating and creative imagination, called bhāvanā, the meditating person identifies with the deity, and can perceive the movement of the Mantras going through the cakras present in his own body. In a particular śakta current, the esoteric Śrīvidyākaula, the central maṇḍala was the Śrīcakra, consisting in nine sets of nesting triangles, arranged in a specific order with a central dot. Each of them is presided over by a group of nine yoginīs. In the hypetral yoginīs temples, discs of stone carrying the figures of the yoginīs became internalized into circle or wheels, lotuses, or cremation grounds of feminine energy within the subtle body of the practitioner. Several tantric texts situate certain yoginīs on specific petals of such internal lotuses. There is a link between the yoginīs and the movement of the heavenly bodies. They appear already in Mahābhārata 1.7.15, where they are Candra’s wives, dwell in the twenty-seven lunar mansions, nakṣatra, said to “regulate the life of the world”.

When three dimensional, the Śrīcakra represents Mount Meru, the mythical mountain at the centre of the world.

In political terms, on the other hand, the cakra symbolizes the absolute power of a universal conquering sovereign, the cakravartin9, the wheels of whose chariot could proceed unimpeded from coast to coast.

Even in contemporary politics and economics the round image is frequently found for its wide appeal, used as a poster for a party’s campaign, or as an extraordinary spherical grand entrance to a commercial mall…

Chronologically, the politico-geographical aspect of both the cakravartin sovereign and the maṇḍala was developed quite early. According to the Arthaśāstra, the king has to take into consideration not only his own territorial sphere of influence (maṇḍala), but also those of his immediate neighbours, traditionally considered his potential enemies, and those of his neighbours’ neighbours, traditionally considered his potential allies. The overlapping of these maṇḍalas, territories that each king tried to constantly expand, were crucial areas for diplomatic relationships between different kingdoms. ‘The central idea of the maṇḍala was to keep a balance of power among a circle of States…’ 10

It is interesting to notice that the Artaśāstra, that considers kings who are in opposition to each other, employs the term cakravartin only once, for such a universal sovereign has already conquered all his opponents. The passage says that «within the earth, between the Himalayas and the sea longitudinally, and one thousand yojanas in extent latitudinally, constitutes the territory of a universal sovereign (cakravartin)»11. In this particular case cakra also means a country, India, extending from sea to sea. At the same time, when called maṇḍala, it was also imbued with a religious meaning, as it represented a sacred space, protected by particular deities, who were often female ones, fierce goddesses of war12.

In the particular Buddhist interpretation, on the other hand, the Buddha is called the cakravartin as he is seen as ‘the one who sets in motion the wheel’ for a different type of conquest. It is the wheel of dharma, the universal Norm, that according to the Buddha should be one and the same for all human beings, irrespective of their origins or beliefs.

In both religious traditions the circular image, moreover, both visually and conceptually, was not intended as a static figure, but represented circular motion, like the wheel of saṃsāra, the ever-repeated cycle of births and deaths, found in the oldest Upaniṣats.

The maṇḍala’s graphic rendering as a circle – or sometimes as a lotus flower – is often contained within a square13, or contains squares or triangles, and in both Hindu, Jain and Buddhist contexts it usually represents the totality of the universe and of the energies/deities at play in it. The physical or mental portrayal of this ensemble has been used as a support for both worship and meditation.

Already some of the oldest śaivite tantric texts, belonging to at least the late fourth century CE, relate that a maṇḍala was drawn during tantric initiation (usually on the floor, with red and white powders). The deities who presided to the ceremony were installed in the maṇḍala, and a flower was thrown in its centre by the blindfolded initiand14 in a particular tantric lineage.

The ritual practice of throwing flowers on to a maṇḍala drawn on the floor, however, is rather old, and does not belong merely to Tantric practice. It is mentioned already in the Nāṭyaśāstra, the oldest Indian dramatic treatise, whose long period of composition, according to the latest studies of Bansat Boudon15, dates from the second century BCE to the first CE. A flower is thrown on the maṇḍala as a feature of the pūrvaraṅga, the initial ritual consecration of the stage, that recalls the first dramatic representation of the fight between gods and anti-gods, in which Indra, the warrior king of the gods, conquered the anti-gods. Indra and the ritual maṇḍala on which the other deities are installed are actually a protection for the performance to come, and flowers are thrown on the maṇḍala because of its sacred function, as an homage to the gods who should then protect the performance.

In the Indian dramatic practice, a complex ensemble involving poetical recitation, music and dance, several dance positions make use of the maṇḍala configuration16. The manuals prescribe the stance called ardhamaṇḍalī ‘half-maṇḍala’, for the classical style Bharatanatyam17, but circular configurations are equally employed in several village choreographies of the round dances performed throughout India by women during the harvest festival, or by fisherwomen dancing to mark particular moments of the fishing season.

Round are also many favourite sweetmeats, and the surprising fruit and vegetables maṇḍala built at Pongal in a traditional pataścāla school in Pondicherry to honour the cows as givers of bounty, like the presiding image of Surabhi, the cow that grants all desire…

Both as terms and images, therefore, Mandalas and cakras have been around since the end of the second millennium BCE and continue to spin.

A full circle embodies the idea of both fullness and completion. In nature, for instance, it is the case of several ripe fruits, full blown lotus flowers, or the sun, as well as the full moon, complete with its sixteen digits, and of all the visible planets.

At times a ritual or auspicious maṇḍala could be inscribed in a square, or be formed by triangles or rhombuses, or be in the shape of a lotus flower.

Commercial advertising imitates nature and makes use of immediately recognizable symbols: the red ad for Indian Vodafone is a set of fourteen perfect circles, plus a few other imperfectly finished ones, organized in a round pattern … It somehow recalls the marvellous round baskets of flowers used to make garlands in the covered flower market of Bengaluru.

On most wrought-iron gates in front of houses, in Pondicherry, circles adorn in many guises the figure of an auspicious woman (with her beautiful saree, large breasts, flowers and jewels), both a protection from the robbers and the giver of light and food. Round are the plates and all the table implements at a popular restaurant where employees flock for lunch from the nearby bank. And the bank advertisement itself, carries a number of round icons, while its logo portrays a man with his arms raised to protect his head, so that it looks like a Mandala formed by a circle surrounded by several squares …

Both in Tamil Nadu and in Karnataka the golam drawn in front of houses are traced with particular care. Here even the wall has received red hand marks, similar to the red and white longitudinal pattern that decorates South Indian temple walls. And later, in the evening, a rickshaw comes to pick us up, its inside decorated like a small boudoir, with a Mandala-like circle of plastic triangles running around the blue light in its ceiling. And all these images recall also the shape of the Śivaliṅga resting on its yoni support in its water cell.

As I was looking at the magnificent marble tree, similar to a wave sculpted in lace, in the fifteenth century Jain temple of Ranakpur, an image that represents frozen, captured movement, it occurred to me that I see maṇḍalas as ritual configurations where energy is contained and arrested by its limiting circular boundary. It is somehow similar to the superficial tension that holds together the molecules of a water drop fallen on a flat surface, giving it a half-spherical shape. Ritual maṇḍalas are also supposed to be beautiful, as «beauty is auspicious»18. As a purely visual expression, however beautiful and vibrant with colours and special powder and substances, maṇḍalas are powerless. In ritual terms, the key to trigger, to free the latent energy they embody, or in other words to animate the frozen maṇḍala, is the correct uttering of the appropriate Mantra19. It is the Mantra formula that summons the deities into the maṇḍala and actuates that potential movement that is at once – or in ordered succession – a centripetal or a centrifugal one, like the moving of inward and outward breath, a contraction followed by an expansion. It is the movement that turns a central point into multiplicity, and that allows multiplicity, the manifested world of forms, to return to the still or pulsating centre. And as Indian cultural manifestations develop in a rather consistent manner, one can even trace a similar process at work in a classical sequence of music, or of dance. In fact, in ritual the Mantras introduce sound in what would otherwise remain a purely visual experience.

These days maṇḍala-like configurations are found also where one would least expect them, not only in all manner of commercial or political ads, but also in patterns on Muslim women veils, or on the advertisements calling the pious to the Haj, just as it could be seen once, as well as now, in the marvellous rounded shape of the tree delicately traced on the arched windows of the Sidi Saiyyed mosque in Ahmedabad, built in 1573.

- Literally ‘the flowing together’.

- Padoux, Tantra, (2011, Italian edition), p. 190.

- Padoux, ibidem, p. 188 (my translation).

- There are also square- or triangle-shaped maṇḍalas, used for specific rituals.

- See for instance A. Boner, S.R. Sarma, B. Baümer (1982), The Vāstusūtra Upaniṣad, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi.

- See C. Sivaramamurti (1955), Sanskrit Literature and Art – Mirrors of Indian Culture. Memoirs of the Archeological Survey of India n. 73, Delhi (pp. 129-133.)

- I am using a masculine form to refer to the meditating person, here, because usually in the ancient tantric texts the adept is a male. Females do appear and take part in the rites, but as dūtīs, ‘messengers’ or ‘consorts’.

- A. Padoux (2010), Comprendre le tantrisme. Les sources hindoues, Albin Michel, Paris.

- ‘He who sets the wheel in motion’, or, according to Kṣīrasvāmin, ‘one who wields lordship over a circle of kings’, or ‘who makes the circle (i.e. the kingdom) abide by his orders’. A more ancient word for ‘emperor’, on the other hand, is sarvabhauma, ‘he to whom the entire earth belongs’.

- P.V. Kane (1946, 3rd ed. 1993), History of Dharmaśāstra, vol. III, p. 222.

- Artaśāstra, 9.1.18, (translation P. Olivelle).

- For a study of the relationship between King and Devī, see F. Baldissera (2016), ‘King and Devī: instances of a special relationship’, in S. Bindi, E. Mucciarelli, T. Pontillo, Cross-cutting Asian Studies: An Interdisciplinary Approach, New Delhi: D.K. Printworld, (pp. 353-388.); for a study on the Warrior Goddess, see for instance Y. Yokochi (2004), The Rise of the Warrior Goddess in Ancient India: A Study of the Myth Cycle of Kauśikī-Vindyavāsinī in the Skandapurāṇa, PhD dissertation submitted to the University of Groningen.

- Interestingly, some maṇḍalas are in the shape of squares containing other squares, or sometimes flowers. See Bühnemann (ed.) et al. (2003), Maṇḍalas and Yantras in the Hindu Traditions., D.K. Printworld Ltd, New Delhi.

- See for instance Abhinavagupta, Tantrāloka, XXIX.vi. 187b-192a, where the initiand is particularly advanced. The point where the flower fell would indicate the name he was going to have after his initiation.

- See L. Bansat-Boudon (1992), Poétique du théâtre indien. Lectures du Nāṭyaśāstra, École Française d’Extrême-Orient, Paris.

- See for instance Kalpana Vatsyan (1983, 2nd ed. 1997), The square and the circle of the Indian arts, Abhinav Publications, New Delhi; and Fabrizia Baldissera, Axel Michaels (1988), Der indische Tanz, Du Mont Verlag, Köln.

- See F. Baldissera, A. Michaels (1988), Der Indische Tanz, Du Mont Verlag, Köln; F. Fratagnoli (2010), Les danses savants de l’Inde à l’épreuve de l’Occident: forms hybrids et contemporaines du religieux, PhD thesis presented at the University of Paris VII.

- This is what is written in Nāṭyaśāstra IV, starting at v. 261, that explains why one dances nṛtta even if it does not tell a story. In particular vv. 264 e 265 say:

kiṃ tu śobhām prajenayed iti nṛttaṃ pravartitam prāyeṇa sarvalokasya nṛttam iśṭaṃ svabhāvataḥ //264//

‘In fact, it should create beauty (śobhā); this is why (= iti) nṛtta was originated; generally nṛtta is desired (= loved) naturally by everyone.

maṅgalyam iti kṛtvā ca nṛttam etat prakīrtitam vivāhaprasavāvāhapramodām yudayādiṣu //265//

‘As it creates auspiciousness, this nṛtta is celebrated (or: ‘is famous’)

at marriages, births, feasts and other happy occasions.’ - It actually consists in a particular sound or succession of sounds… Any type of worship needs its appropriate Mantra. The beginning of the chapter on Mantras of the Vātulaśuddhāgama says «The Mantras are the form of the gods, and the world is the form of the Mantras», in H. Brunner-Lachaux (1963), Introduction, (Somaśambhupaddhati vol. I, Institut Français d’Indologie, Pondicherry, (pp. XXX-XXXI.)