Wouter Hanegraaff

CLOSE ENCOUNTERS WITH THE THIRD KIND: A HERMETIC THEORY OF IMAGINAL CONSCIOUSNESS

In this essay, Wouter Hanegraaff analyzes a neglected theory of consciousness and the imagination central to Hermetic literature. Corpus Hermeticum XI, in particular, describes a radical state of consciousness expansion referred to as the Aiōn, in which the human mind is said to participate completely and consciously in the “incorporeal imagination” of the universal divine mind or Nous. By going back to the original terminology and its intellectual context in late antiquity, Wouter Hanegraaff brings to light a theory of consciousness that has been forgotten and misunderstood, but may prove highly relevant to current discussions in philosophy and cognitive research.

Marble portrait bust of Plato (428-248 BCE) dating back to the IV century BCE. Capitoline Museum, Rome. Source: DeAgostini/SuperStock. In: britannica.com/biography/Plato.

Marble portrait bust of Plato (428-248 BCE) dating back to the IV century BCE. Capitoline Museum, Rome. Source: DeAgostini/SuperStock. In: britannica.com/biography/Plato.The so-called Hermetic treatises were written by anonymous authors in Roman Egypt during the first centuries CE. They are very well known to scholars as important historical sources for popular philosophy and religion in late antiquity, but have almost never been approached from the perspectives of psychology and consciousness studies1. In this short article I argue that in actual fact, they contain a subtle and fascinating theory of consciousness grounded in classic post-Aristotelian views of the imagination (phantasia). The intellectual tradition from which these texts emerged has been neglected and marginalized to a truly remarkable extent between antiquity and the eighteenth century, when some of its basic insights were rediscovered and reinstated by Kant and Fichte – only to be covered up once again, first by Kant himself and then by Hegel2. The crucial importance and continuing relevance, for philosophy and the study of consciousness, of these theories of the imagination has nevertheless been emphasized in different ways notably by Martin Heidegger (who rediscovered the Kantian theory), Cornelius Castoriades (who did the same for the original Aristotelian perspective), and Chiara Bottici (who has sought more recently to restore it to the agenda of political philosophy and critical theory). My larger argument is that the human faculty of imagination (phantasia in Greek, Vorstellungsvermögen or Einbildungskraft in German3), as theorized in this tradition, may well be of key importance for understanding the nature of human consciousness. To explore the connection from a systematic perspective, modern specialists in the study of consciousness can look for inspiration and important insights to classical theories and approaches that have seldom received the attention they deserve.

Plato’s Chōra and Aristotle’s Phantasia

Classical Greek metaphysics distinguished famously between the realm of Being and that of Becoming. In Plato’s Timaeus, for instance, these “two basic kinds” (eidē) were formulated in technical language. To understand the important passage in question, we first need to be aware of a crucial but severely neglected issue concerning translation. The Greek word nous is conventionally translated as “mind” or “intellect”; and its activity, noēsis, is most frequently rendered as “thinking.” However, these standard lexical translations do a very poor job at conveying the actual meanings of nous and noēsis in ancient philosophy, whether Platonic or Hermetic. In fact, they obscure the very nature of these “noetic” processes of human cognition, by using philosophical language that sounds comfortable to modern readers but is far removed from the original meaning. The sober truth is that modern English has no words that even approximate the subtle meanings of nous and noēsis in ancient Greek philosophy – these terms are strictly untranslatable4. It is for this reason that on the following pages I introduce the verb noeticizing, as a neologism necessary to capture the activity of nous.

With these observations in the back of our minds, we are now ready to read the following key passage in Plato’s oeuvre about Being and Becoming:

… the following must first be distinguished: what is that which always is [to on aei] and has no coming-to-be, and what is always coming to be [to gignomenon aei] and never is? The former is to be noeticized with the help of logos [noēsei meta logou], being always the same, but the latter is to be opined by opinion [doxēi] with the help of unreasoning sense perception [aisthēseōs alogou], coming to be and passing away but never really being.5

Thus the timeless noetic reality of “what really is” stands against our perceptual space-time reality of impermanence and multiplicity, sense perception and mere opinion. So far, so good. Notoriously, however, Plato was preparing the way here for his later introduction of a third “kind” – something baffling and utterly mysterious referred to as the chōra. While the passage in question may seem obscure or enigmatic at first sight, that impression results in fact from the extreme precision of its formulations. It therefore deserves to be read with the utmost care:

… there is a third kind, the everlasting chōra [triton de au genos on to tēs chōras aei] which does not receive destruction, which provides an abode [hedran] for everything that comes to be, but is itself apprehended without sense experience [met’ anaisthēsias] by a kind of bastard reasoning [logismōi tini nothōi], hardly trustworthy; which we see as in a dream, and affirm that it is necessary for all that is to be somewhere in some place and occupy some chōra; and that that which is neither on the earth nor in heaven is nothing.6

Regardless of how we interpret the exact nature of this chōra (if indeed it can be interpreted at all), there is broad agreement among specialists that by introducing this “third kind,” Plato utterly deconstructs the dualism of eternal Being versus ever-changing Becoming7. While the chōra is everlasting like Being, yet it functions like a necessary, indispensable substrate or receptacle of everything that pertains to the domain of Becoming; it is imperceptible to the senses and cannot be grasped by proper or legitimate reason; and since it neither is nor becomes, one can only refer to it as “nothing.” Therefore is it or is it not? Somehow it must be neither or both. While the chōra lacks any formal qualities, it both receives and reveals them; while it never appears itself, yet it makes everything apparent.8 We cannot presume to know with absolute certainty what Plato meant by chōra, but I suggest it would be perfectly natural for readers in antiquity to be reminded of another concept – that of Aristotle’s phantasia, the imagination. In a famous passage of De anima, he observes that internal images (phantasmata) appear to the noeticizing soul as objects of perception, which it then avoids if they seem bad and pursues when they seem good. Thus it is, he notes, that “the soul never noeticizes without a phantasm” (oudepote noei aneu phantasmatos hē psuchē).9 This elusive faculty of imagination never appears directly or independently, but only through what it does; it is “different from either sense perception or discursive thinking (dianoia), although it is never found without sense perception”10; and it enables human consciousness to store images and remember them. Commenting on Plato’s statement that the chōra escapes our proper faculty of reasoning and is seen only “as in a dream,” John Sallis has made the perceptive remark that what we see in our dreams is always “an image that goes unrecognized as an image, an image that in the dream is simply taken as the original” – one must be awake to distinguish between the two11. Most modern readers experience some difficulties in grasping the point at issue here, and its implications, because it seems to conflict with our default post-Enlightenment assumptions about fantasy and imagination as contrary to rational knowledge and the reality principle. However, this difficulty of understanding in fact illustrates the very problem of translation that I already highlighted with reference to nous and noēsis: as it happens, the Greek word phantasia has no proper equivalent in our modern languages either. As explained in a meticulous analysis by Chiara Bottici,

The contrast [of phantasia] with the modern view of imagination as purely imaginary could not be greater. The proportions of this rupture are evident in the embarrassment of modern translators who cannot render the Greek term phantasia with the literal translation “fantasy” because this would mean the opposite of what Aristotle had in mind when writing those passages. Alternative modern terms are needed to capture the meaning of Aristotle’s phantasia: “actual vision” or “true appearance,” that is, expressions that mean exactly the opposite of what literal translations such as “imagination” and “fantasy” would convey to modern readers.12

Therefore the term phantasia did not refer to mental delusions or creative inventions divorced from reality, as we usually assume: it meant simply “appearance” or “presentation,” from phainesthai (to appear)13. As such, it covered absolutely everything that appears to be present in human consciousness. In stating that “the soul never noeticizes without a phantasm,” Aristotle therefore referred to the imagination as nothing less than “the condition for thought insofar as it alone can present to thought the object as sensible without matter.”14 In other words, no mental or intellectual activity of any kind is considered possible without the faculty of imagination: “there is always phantasm; we are always imagining.”15 Because this point is obscured by our common understandings of “imaginative” or “imaginary” as not cognitive but delusionary or deceptive, I adopt Chiara Bottici’s convention of using imaginal as an adjective that makes no assumptions either way about the reality of what is being perceived16.

The Hermetic Aiōn

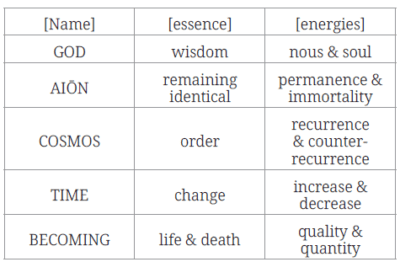

Against these backgrounds, I wish to call the reader’s attention to an important Greek treatise known as Corpus Hermeticum XI, in which the pupil Hermes Trismegistus receives instruction from no one less than the personified Nous itself, understood in a Hermetic context as the ultimate divine reality of universal Light. Here the Nous calls Hermes’ attention precisely to a “third kind” of reality intermediary between God and the Cosmos but not reducible to either of those two. It undercuts the dualism of Being and Becoming just as the chōra does in Plato’s Timaeus, but here this third kind is referred to as the aiōn. As an introduction, Hermes is first presented with a systematic overview of how the whole of reality is structured. There is a hierarchy of five levels, each one of which is the source of the one below it: from God comes the aiōn, from the aiōn comes the Cosmos, from the Cosmos comes Time, and from Time comes Becoming. Each level is said to have an essence (ousia) and two energies (energeiai).17

The term phantasia did not refer to mental delusions or creative inventions divorced from reality, as we usually assume: it meant simply “appearance” or “presentation,” from phainesthai (to appear).

This structure is less complicated than it might seem at first sight. That the Ptolemaic geocentric cosmos with its continuous circular movement of the planetary spheres brings forth time was a perfectly standard assumption; and that “becoming” depends on time is equally obvious. The three lower levels therefore belong together as the cosmic domain of time and change. Thus it is easy to simplify this five-part division by reducing it to a more basic triple division: God – Aiōn – The World (= Cosmos/Time/Becoming). The result is a familiar standard structure in which eternal Being (God) is pitted against Becoming (the world) – but with the aiōn added in between, as a surprising “third kind” that apparently neither is nor becomes, or does both at the same time. CH XI continues by explaining that while God is the ultimate source (pēgē) of all things, the aiōn is their true being (ousia); more specifically, it is the divine power or soul that allows the cosmos to function and move. As it always remains identical, it is imperishable, indestructible, immortal, and wholly envelops the cosmos.18

Before the teaching returns to the aiōn, Hermes is now invited to look at the cosmos through the eyes of the Nous itself (theasai de di’ emou…). As with earlier instances in the Hermetic literature (notably a passage in which the pupil’s attention is called to the innocence of a newborn baby19) what this means is that he must look with a gaze of wonder and love:

behold the cosmos as it extends before your gaze, and carefully contemplate [katanoēson] its beauty: a flawless body, while older than anything else, yet always in bloom, young and flourishing in ever more abundance.20

The text continues to praise this supreme spectacle of cosmic splendour: all is filled with divine Light and Love, everything is full of soul and in never-ending harmonious movement,21 and the whole is forever held together by the universal goodness of God alone: “one single soul, one single life, one single matter.”22 As the central power of creative abundance, the generative Source in its boundless generosity never stops giving birth to all that is. “And that, dear friend, is life. That is beauty. That is goodness. That is God.”23

So here we have Hermes looking at the cosmos with what the Hermetic literature often refers to as “the eyes of the heart,” the internal gaze of wonder and love, marvelling at the beauty of it all. It is at this point that his teacher makes a characteristically Hermetic request for extra concentration24: some of my words require special attention, so please try to understand [noēson] what I’m about to say now!25 And what follows is important indeed. As Hermes is looking at the cosmos, what is he really looking at? This is what the nous explains to him:

All beings are in God – not as though they were in some place … but in a different manner: they rest in his incorporeal imagination [en asōmatōi phantasiāi]. … You must conceive of God as having all noēmata in himself: those of the cosmos, himself, the all. Therefore unless you make yourself equal to God, you cannot understand [noēsai] God. Like is understood only by like. Allow yourself to grow larger until you are equal to him who is immeasurable, outleap all that is corporeal, transcend all time, and become the aiōn – then you will understand [noēseis] God.26

Ancient marble portrait of Aristotle (384-322 BCE). Roman copy (II century BCE) of a Greek original (c. 325 BCE). Museo Nazionale Romano, Rome (Italy). Source: A. Dagli Orti/©De Agostini Editore/age fotostock. In: britannica.com/biography/Aristotle.

Ancient marble portrait of Aristotle (384-322 BCE). Roman copy (II century BCE) of a Greek original (c. 325 BCE). Museo Nazionale Romano, Rome (Italy). Source: A. Dagli Orti/©De Agostini Editore/age fotostock. In: britannica.com/biography/Aristotle.Regretfully, modern specialists of the Hermetic treatises have almost universally ignored the request for special attention, for the abundant critical literature shows a singular lack of interest in precisely this key passage about the incorporeal imagination.27 We find lengthy and erudite discussions of what the word aiōn could mean in late antiquity, but no recognition or discussion of what our text so clearly says: that here this term refers to God’s incorporeal imagination filled with the noēmata of all that is.28 And yet, precisely that statement is of key importance for CH XI as well as for the important parallel treatise CH XIII, the famous treatise on rebirth.29 According to the Hermetic literature, our normal human consciousness gets deluded on a constant basis by the “phantom images” of the imagination. These must be distinguished from the supreme true image of the divine Monas: while the former belong to the realm of change and Becoming, the latter stands for permanent Being. But in CH XI we are presented with a third kind of imaginal awareness. Unlike the other two, this is not an inherently limited perspective “from somewhere” (for even the supreme image of the Monas described in CH IV 9-11 will still be perceived by one single human consciousness as it freshly emerges, in Platonic terms, from the cave of impermanence and multiplicity) but the eternal divine perspective from everywhere. In other words, this is not the image of God as it appears to human consciousness, but the All as it is perceived in God’s own consciousness. Whereas isolated images that appear in human consciousness attract our selfish desires, so that we pursue them and end up getting enslaved in matter, the point is that God perceives all images simultaneously. He feels no need to pursue any of them, because he already possesses them all and privileges none over the other; therefore this universal divine consciousness alone is perfectly free from the limiting temptations of desire. The truly remarkable statement made by CH XI is that human consciousness is not separate from this divine consciousness but is capable of full participation in its universal mode of imaginal perception.

Behold [noēson] him who contains all that is, and behold [noēson] that there are no boundaries to the incorporeal, that nothing is quicker or more powerful. … You can see [noēson] this for yourself. Tell your soul to travel to India, and it will be there faster than your command. Tell it to go to the ocean, and again it will be there quite as quickly – not as though it were moving from one place to another but as though it was always already there. Then tell it to fly to heaven, and you will find that it needs no wings. Nothing can stop it, neither the fire of the sun, nor the ether, nor the cycles of the stars, nor the other heavenly bodies. Cutting through all spaces, its flight will carry it all the way up to the ultimate corporeal thing. And if you wish to break through the outer rim of the cosmos to see what is beyond it (if anything beyond the cosmos can be said to be), you can do even that. See what power you have, what quickness! … Having perceived that nothing is impossible for you, consider yourself immortal and capable of understanding [noēsai] everything – all arts, all learning, the nature of all living beings. Rise higher than every height and descend lower than every depth; gather all sensations inside you of all that is made – fire, water, dry and humid. Be everywhere at once: on earth, in the sea, in heaven, before you were born, in the womb, young, old, dead, in the hereafter. If your nous can behold all these things simultaneously [noēsas] – times, places, actions, qualities, quantities – then you can know [noēsai] God.31

Again and again we are faced with the difficulty of translating the Greek terminology of noēsis (“behold,” “see,” “understand,” “know”) for which we may have to learn using a neologism such as “noeticizing.” The passage makes clear that the activity of nous is perceptual and not just conceptual, imaginal rather than just intellectual in our narrow post-cartesian sense of that term.32 In Aristotelian terms, God himself “never noeticizes without a phantasm”; but the point is that in Hermetic terms, he never does so without all phantasms! If indeed the human soul could participate in this universal consciousness, it would evidently be freed from its enslavement to the bodily senses, which limit and constrict our field of perception by forcing our consciousness to concentrate always on just one particular time and one particular place to the exclusion of all others. Hence the significance of the final sentences: this is not about some kind of Superman ability to travel through the universe with the speed of light, but about the possibility of being consciously present at all times and in all places simultaneously (homou). This universal consciousness is described as God’s “incorporeal imagination” and referred to as the aiōn.

It is therefore misleading to translate aiōn simply as “eternity,” as in most modern translations.33 From Homer through the Hellenistic period and into the Christian era, the word could be interpreted as long or even infinite duration or as timeless eternity, but could also mean the human life force or source of vitality. In the central tradition of Parmenides and Plato, aiōn was understood as a monas in which temporal distinctions were all present together, and Plato seems to have thought of it as a living being.34 Keeping in mind that time itself was described as a phantasma by Democritus and probably Epicurus as well,35 an interpretation of aiōn as God’s incorporeal imagination (phantasia) makes perfect sense. Exactly like the chōra in Plato’s Timaeus, in CH XI it functions as a “third kind” that cannot be reduced to either Being or Becoming but mediates between the divine noetic world and the material world of the senses. As such, it transcended the limits not just of time, but those of space as well. In terms of modern philosophy it is remarkably similar to the crucial Kantian concept of the transcendental imagination (transzendentale Einbildungskraft) that allows noumena to be perceived as phenomena (appearances) in human consciousness.36

It is significant that on no less than three different occasions, the Hermetica explain human perception by the analogy of a painting, pointing out that although we actually look at a flat surface we see images that give the illusion of three-dimensionality. Thus the Nous explains to Hermes in CH XI 17, again with that characteristic request for special attention (“try to understand noetically [ennoēson] what I’ve been telling you…”),37 that the notion of an incorporeal idea, a word that comes from idein (“seeing”), is not so astonishing as he might think: “on paintings you may see mountain ridges rise up in sharp relief although the painted surface is actually smooth and even.”38 Likewise, Hermes says in the Asclepius that we think the world is visible “because of the forms of species that seem to be imprinted on her as images …. similar to a painting”39 But in fact, he insists, the world is not visible. Finally, the same point is made in one of the Stobaean fragments.40 All these passages reach the same conclusion: what makes vision possible must itself be invisible, that which allows things to appear must forever dis-appear. Today the Hermetic authors might have said that our daily perception of phenomenal reality is similar to watching a movie: one needs a projection screen and one needs to be unaware of its presence.

In CH XI, the Nous tells Hermes explicitly that learning to participate in God’s own imaginal consciousness is the indispensable key to gnōsis, ultimate salvational knowledge. Such knowledge is impossible in our normal state of restricted consciousness, because

… if you shut your soul up in your body and humiliate it, saying “I can know nothing [ouden noō], I can do nothing, I fear that celestial ocean,41 I cannot rise to heaven, I do not know what I have been, I do not know what I will be,”42 then what do you have to do with God? Then you are powerless to know [noēsai] anything beautiful or good, in love with the body and bad as you are. For ignorance of the divine is the worst defect there is. But to be capable of knowing him [gnōnai], to wish it and hope for it, is the straight and easy path that leads directly to the good. On that road he will meet you everywhere, you will see him everywhere, at places and times where you least expect it, while waking or sleeping, on sea or on earth, at night or in daytime, while you speak or as you’re silent – for there is nothing that he is not.

So will you say “God is invisible”? Don’t speak like that. Who is more visible than he is? He has made everything so that you might see him through all that is. That is God’s goodness, therein lies his excellence: to make himself apparent through all that is. For nothing is invisible, not even among the incorporeals. Nous shows itself in the act of noēsis, God in the act of creating.43

There is no conflict between the strongly world-affirming perspective of CH XI as a whole and the message that divine knowledge will escape those who are “in love with the body.” Note that problem lies not in the body as such, but in a limited consciousness that “shuts the soul up in the body” and allows it to be dominated by the negative passions.44 The soul must be liberated from enslavement by opening its eyes to the beauty and goodness of divinity that literally surrounds it on all sides.

What makes vision possible must itself be invisible, that which allows things to appear must forever dis-appear.

Concluding Remarks

To recover the relevance of these classical views for modern discussions of consciousness and the imaginative faculty – or rather, to even begin grasping their meaning at all – we need to cross a formidable abyss of understanding and translation. Our very word “translation” comes from the Latin translatus, the past participle of transferre, “to carry across.” The German übersetzen (“setting across,” as for instance in lifting something up from a river’s shore and putting it down on the other side) makes the same point, as does the French traduire (viz. transducere, “leading across”). All these words reflect the very acute insight that what happens in any act of translation is always a transfer of meaning across a liminal space of radical discontinuity. Concerning the most central vocabulary of classical Greek philosophy, it is routine practice to translate nous as “mind” or “intellect,” noēsis as “thinking,” and logos as “word,” “speech,” or “reason,” and we are completely used to conducting our scientific and philosophical discussions of consciousness in these and similar modern terms. As a result, we have lost touch with some of the core assumptions, insights, contexts, and understanding that informed the philosophical traditions of which we claim to be the heirs. One does not have to agree with Martin Heidegger’s philosophical system to agree with his basic observations about what happened to logos and nous in the course of Western intellectual history:

Elohim Creating Adam (1795c.1805) by William Blake (1757-1827).

Elohim Creating Adam (1795c.1805) by William Blake (1757-1827).Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Thinking becomes the legein [saying] of the logos in the sense of uttering a proposition. At the same time, thinking becomes noein in the sense of apprehension by reason [die Vernunft]. The two definitions are coupled together, and thus determine what is henceforth called thinking in the Western-European tradition. The coupling of legein and noein as proposition and reason are distilled in what the Romans call ratio. Thinking now appears as what is rational. … Ratio becomes reason [Vernunft], the domain of logic. But the original nature of legein and noein disappears in ratio. As ratio assumes the dominant position, all relations are turned upside down; for medieval and early modern philosophy now explain the Greek essence of legein and noein, logos and nous, in terms of their own concept of ratio. But that explanation no longer illuminates – it obfuscates.45

Giving the unquestionable centrality of precisely these terms to what “thinking” is supposed to mean in Western intellectual history, this is no small matter. It may be comfortable for us to think of intellectual developments between Greek antiquity and modern philosophy as a history of progress in which ancient but incorrect ideas have given way to better, new and more adequate concepts. But before considering such an interpretation, congenial as it may be to our own cherished beliefs and default assumptions, we should explore the alternative possibility that we may have lost sight of acute insights about the nature of consciousness and the imagination simply because we no longer understand what they meant.

Abbreviations

Ascl.: Asclepius (Latin in Nock & Festugière, Hermès Trismégiste, vol. 2).

CH: Corpus Hermeticum (Greek in Nock & Festugière, Hermès Trismégiste, vols. 1-2).

HD: Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius (Armenian in Mahé, Hermès Trismégiste, vol. 5).

SH: Stobaean Hermetica (Greek in Nock & Festugière, Hermès Trismégiste, vols. 3-4).

Bibliography

Banner, Nicholas, Philosophic Silence and the “One” in Plotinus, Cambridge University Press 2018.

Böhme, Hartmut & Gernot Böhme, Das Andere der Vernunft: Zur Entwicklung von Rationalitätsstrukturen am Beispiel Kants, Suhrkamp: Frankfurt a.M. 1983.

Bottici, Chiara, Imaginal Politics: Images Beyond Imagination and the Imaginary, Columbia University Press: New York 2019.

Broek, Roelof van den & Gilles Quispel (eds.), Hermetische Geschriften, In de Pelikaan: Amsterdam 2016.

Bull, Christian H., The Tradition of Hermes Trismegistus: The Egyptian Priestly Figure as a Teacher of Hellenized Wisdom, Brill: Leiden / Boston 2018.

Camassa, Giorgio, “Phantasia di Platone ai neoplatonici,” in: Fattori & Bianchi, Phantasia – Imaginatio, 23-55.

Castoriadis, Cornelius, The Imaginary Institution of Society, Polity Press: Cambridge / Malden 1987.

—-, “The Discovery of the Imagination,” in: World in Fragments: Writings on Politics, Society, Psychoanalysis and the Imagination, Stanford University Press 1997, 213-245.

Colpe, Carsten & Jens Holzhausen (eds.), Das Corpus Hermeticum Deutsch, 2 vols., fromman-holzboog: Stuttgart / Bad Cannstatt 1997.

Copenhaver, Brian P., Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction, Cambridge University Press 1992.

Derrida, Jacques, On the Name, Stanford University Press 1995.

Fauconnier, Gilles & Mark Turner, The Way We Think: Conceptual Blending and the Mind’s Hidden Complexities, Basic Books: n.p. 2003.

Festugière, André-Jean, La révélation d’Hermès Trismégiste, 4 vols., Les Belles Lettres: Paris 1942, 1949, 1953, 1954 (repr. in one volume 2006).

Fowden, Garth, The Egyptian Hermes: A Historical Approach to the Late Pagan Mind, Princeton University Press 1986.

Fritz, Kurt von, “Νοῦς and νοεῖν in the Homeric Poems,” Classical Philology 38:2 (1943), 79-93.

—-, “Νοῦς and νοεῖν and their Derivatives in Pre-Socratic Philosophy (excluding Anaxagoras), Part I: From the Beginnings to Parmenides,” Classical Philology 40:4 (1945), 223-242.

—-, “Νοῦς and νοεῖν and their Derivatives in Pre-Socratic Philosophy (excluding Anaxagoras), Part II: The Post-Parmenidean Period,” Classical Philology 41:1 (1946), 12-34.

Godel, R., “Socrate et Diotime,” Bulletin de l’Association Budé: Lettres d’humanité 13 (1954), 3-30.

Hanegraaff, Wouter J., “Religion and the Historical Imagination: Esoteric Tradition as Poetic Invention,” in: Christoph Bochinger & Jörg Rüpke (eds.), in cooperation with Elisabeth Begemann, Dynamics of Religion : Past and Present, De Gruyter: Berlin 2017, 131-153.

—-, “Carl August von Eschenmayer and the Somnambulic Soul,” in: Lukas Pokorny & Franz Winter (eds.), The Occult Nineteenth Century: Roots, Developments, and Impact on the Modern World, Palgrave MacMillan: Cham 2021, 15-35.

—-, Hermetic Spirituality and the Historical Imagination: Altered States of Knowledge in Late Antiquity, Cambridge University Press 2022.

Heidegger, Martin, Was heisst Denken?, Vittorio Klostermann: Frankfurt a.M. 2002.

—-, What Is Called Thinking?, Harper & Row: New York / Evanston / London 1968.

—-, Kant und das Problem der Metaphysik (Gesamtausgabe I.3), Vittorio Klostermann: Frankfurt a.M. 1991.

Hyland, Drew A., Questioning Platonism: Continental Interpretations of Plato, State University of New York Press: Albany 2004.

Iamblichus, Réponse à Porphyre (De Mysteriis) (Henri Dominique Saffrey & Alain-Philippe Segonds, ed. & transl.), Les Belles Lettres: Paris 2018.

Kingsley, Peter, “An Introduction to the Hermetica: Approaching Ancient Esoteric Tradition,” in: van den Broek & van Heertum, From Poimandres to Jacob Böhme, 17-40.

Kneller, Jane, Kant and the Power of Imagination, Cambridge University Press 2007.

Leyden, W. von, “Time, Number, and Eternity in Plato and Aristotle,” The Philosophical Quarterly 14:54 (1964), 35-52.

Mahé, Jean-Pierre, Hermès en Haute-Égypte, vol. 1: Les textes Hermétiques de Nag Hammadi et leurs parallèles grecs et latins, Les Presses de l’Université Laval: Québec 1978.

—-, Hermès en Haute-Égypte, vol. 2: Le fragment du Discours Parfait et les Définitions Hermétiques Arméniennes, Les Presses de l’Université Laval: Québec 1982.

—-, Hermès Trismégiste, Tome 5: Paralipomènes grec, copte, arménien – Codex VI de Nag Hammadi – Codex Clarkianus 11 Oxoniensis – Définitions Hermétiques, Divers, Les Belles Lettres: Paris 2019

Mansfeld, Jaap & Oliver Primavesi, Die Vorsokratiker, Philipp Reclam: Stuttgart 2012.

Miller, Dana R., The Third Kind in Plato’s Timaeus, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: Göttingen 2003.

Morenz, S., La religion égyptienne, Payot: Paris 1962.

Moreschini, Claudio, Dall’Asclepius al Crater hermetis: Studi sull’ermetismo latino tardo-antico e rinascimentale, Giardini: Pisa 1985.

Nock, A.D. & A.-J. Festugière, Hermès Trismégiste, 4 vols. (1946, 1954), Les Belles Lettres: Paris 1991, 1992, 2002, 2019

Nussbaum, Martha Craven, Aristotle’s De motu animalium: Text with Translation, Commentary, and Interpretive Essay, Princeton University Press 1978.

Reitzenstein, Richard, Review of Scott, Hermetica vol. 2, Gnomon 3:5 (1927), 266-283.

Salaman, Clement, Dorine van Oyen & William D. Wharton (eds.), The Way of Hermes: The Corpus Hermeticum / The Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius, Duckworth: London 1999.

Sallis, John, Chorology: On Beginning in Plato’s Timaeus, Indiana University Press: Bloomington / Indianapolis 1999.

Schulte-Sasse, Jochen, “Einbildungskraft / Imagination,” in: Karlheinz Barck, Martin Fontius, Dieter Schlenstedt, Burkhart Steinwachs & Friedrich Wolfzettel (eds.), Ästhetische Grundbegriffe: Studienausgabe, vol. 2, J.B. Metzler: Stuttgart / Weimar 2010, 88-120.

Scott, Walter, Hermetica: The Ancient Greek and Latin Writings which contain Religious or Philosophic Teachings ascribed to Hermes Trismegistus, 4 vols. (orig. 1924, 1925, 1926, 1936), repr. Shambhala: Boston 1985/1993.

Shaw, Gregory, “The Chôra of the Timaeus and Iamblichean Theurgy,” Horizons 3:2 (2012), 103-129.

Van den Kerchove, Anna, La voie d’Hermès: Pratiques rituelles et traités hermétiques, Brill: Leiden / Boston 2012.

—-, Hermès Trismégiste, Éditions Entrelacs: Paris 2017.

Warnock, Mary, Imagination, University of California Press: Berkeley / Los Angeles 1976.

Endnotes

- The argument outlined in this article is part of a larger book-length treatment in which I try to remedy this situation: Hanegraaff, Hermetic Spirituality and the Historical Imagination: Altered States of Knowledge in Late Antiquity (Cambridge University Press 2022). Among the most important standard works are Festugière, La révélation d’Hermès Trismégiste (4 vols.); Mahé, Hermès en Haute-Égypte (2 vols.); Fowden, The Egyptian Hermes; Van den Kerchove, La voie d’Hermès; and Bull, Tradition of Hermes Trismegistus.

- See notably Castoriadis, “Discovery,” 215; Schulte-Sasse, “Einbildungskraft/Imagination,” 89-93; Bottici, Imaginal Politics. For Kant’s cover-up between the first and second edition of Kritik der reinen Vernunft, see Heidegger, Kant und das Problem, 126-132; Böhme & Böhme, Das Andere der Vernunft, 231-250; Warnock, Imagination, 13-71; Kneller, Kant and the Power of Imagination, chs. 1 and 5. For Fichte and Hegel, see Castoriadis, o.c., 214-215; idem, Imaginary Institution of Society, 391-392 note 53.

- The differences between Vorstellungsvermögen and Einbildungskraft would deserve a separate discussion. For a short discussion at the example of an early nineteenth-century pioneer of consciousness studies, see Hanegraaff, “Carl August von Eschenmayer,” 22-23 with note 8.

- E.g. Banner, Philosophic Silence, 187; Godel, “Socrate et Diotime,” 26 with note 58. For discussion, see Hanegraaff, Hermetic Spirituality, pp. ***.

- Plato, Tim. 27d5-28a4; cf. Miller, Third Kind, 41-42.

- Plato, Tim. 52a-b (with very slight adaptations in the interest of readability; cf. translations in Sallis, Chorology, 118, and Hyland, Questioning Platonism, 116-117).

- Hyland, Questioning Platonism, 109-122 (here 114), with an important critique of Derrida’s influential analysis in On the Name, 89-127 (as summarized by Shaw, “Chôra,” 108, “Derrida deconstructs a house that was never built, at least not by Plato or his Neoplatonic successors”); Sallis, Chorology, 91-124; Miller, Third Kind.

- Shaw, “Chôra,” 111.

- Aristotle, De anima III.7.431a. See parallel statements in III.7 and 8, and in De memoria quoted in Castoriadis, “Discovery,” 233; and see discussion in Hanegraaff, Hermetic Spirituality, Chapter Seven, pp. ***. As noted by Castoriadis, the proposition was intended to be “universal, absolute, without restriction” (o.c., 239).

- Aristotle, De anima III.3.427b.

- Sallis, Chorology, 121. At the expense of its radical nonduality, chōra was identified with matter (hulē) by the time of the Middle Platonists, and Plotinus concluded that matter itself was incorporeal, “a sort of fleeting frivolity … nothing but phantoms” (Enn. III.6.7; see Sallis, o.c., 151). As pointed out by Sallis, Kant’s concept of the transcendental imagination in the first edition of his Kritik der reinen Vernunft is in fact “a reinscription of the chorology” (o.c. 155).

- Bottici, Imaginal Politics, 20-21.

- Bottici, op. cit., 20. On φαντασία as derived from φαίνεσθαι, see Camassa, “Phantasia da Platone ai neoplatonici,” 23-25; Bottici, op. cit, 20 with 206 note 18: our understanding of the imagination as a creative faculty appears “only very late and very rarely.” For a longer discussion, see Nussbaum, Aristotle’s De Motu Animalium, 221-273 (with reservations: Bottici, op. cit., 20-21 with 207 note 20).

- Castoriadis, “Discovery,” 231 (note that “sensible” potentially refers to all the senses, not just visuality).

- Castoriadis, op. cit., 228., 235-236; and see references to Aristotle on p. 233. Modern cognitive reseach confirms that “imaginative operations of meaning construction … work at lightning speed, below the horizon of consciousness” (Fauconnier & Turner, The Way We Think, 8; Hanegraaff, “Religion and the Historical Imagination,” 133-135).

- Bottici, Imaginal Politics, 57: “in contrast to the unreal and fictitious, which is associated with the imaginary, the imaginal has no embedded ontological status; it makes no assumption as to the reality of the images that fall within its conceptual domain.” It is important to note that such a “radically agnostic” understanding of the imaginal runs counter in that respect to the original perspective of authors such as Henry Corbin (who introduced the term to current philosophical debate) or James Hillman (ibid., 58-59; cf. Hanegraaff, Hermetic Spirituality, Epilogue, p. 367 note 55).

- CH XI 2. Following Nock and Festugière (Hermès Trismégiste, vol. I, 147), I see τὸ ἀγαθόν, τὸ καλόν, ἡ εὐδαιμονία as a scribal error. Whereas in CH XI 2 these words have no clear function and are stylistically out of place, they appear in CH XI 3 as a clear response to Hermes’ question about the nature of wisdom; therefore I assume that “wisdom” is meant to be the primary term (contrary to Scott, Hermetica, vol. I, 206, who leaves out ἡ σοφία instead of τὸ ἀγαθόν). Scott’s addition of ποσότης (quantity) seems perfectly reasonable and has been universally adopted.

- CH XI 3.

- CH X 15 (see discussion in Hanegraaff, Hermetic Spirituality, 198).

- CH XI 6.

- CH XI 7-8. Several commentaries ( & Festugière, Hermès Trismégiste, vol. I, 159 note 23; Colpe & Holzhausen, Corpus Hermeticum Deutsch, 127 note 355) are painfully blind to the obvious meaning of divine “light” and “love” (conjunction of opposites and contraries) in this passage. For the explicit distinction between light and fire, cf. HD II 6 (Mahé, Hermès Trismégiste, vol. 5, 222-223; and note that the light appears wholly “as it is in itself”: it is not a phenomenal appearance but a noumenal reality).

- CH XI 11. This direct equivalence of divine light with soul, life, and even matter (ὕλη) is a particularly strong confirmation of the radical nondual perspective of CH XI and indeed of the “spiritual” Hermetica as a whole (as argued at length in Hanegraaff, Hermetic Spirituality).

- CH XI 13. Since God is only life and abundance, what we call death and dissolution is really just change and transformation (CH XI 14-15); see discussion in Hanegraaff, Hermetic Spirituality, 271-274.

- On these characteristically Hermetic requests for special attention and concentration, see Kingsley, “An Introduction,” 33-35, 38-39; Moreschini, Dall’Asclepius, 81; Van den Kerchove, Hermès Trismégiste, 84; Hanegraaff, Hermetic Spirituality, p. 62, note

- CH XI 18.

- CH XI 18 and 20.

- See the close parallel with CH V 1, discussed in Hanegraaff, Hermetic Spirituality, 231. Scott, Hermetica, vol. I, 218-219 puts φαντασίᾳ within brackets (!) and distorts the original so completely that his translation does not even remotely reflect the original. Nock & Festugière, Hermès Trismégiste, vol. I, 154 have “représentation,” without a footnote. No commentary in Copenhaver, Hermetica, 172, 133 (“Vorstellungskraft,” no footnote); Van den Broek & Quispel, Hermetische Geschriften, 146 (“het zuivere denken van God”: “the pure thinking [!] of God,” no footnote).

- Festugière’s 60-page discussion of CH XI and the aiōn (La révélation, vol. 4, 141-199) manages to overlook almost everything of importance. From p. 146 on, he vanishes down a rabbit hole of extreme erudition in pursuit of the word αἰών, distinguishing seven possible meanings, of which the first two are considered relevant, but at the expense of what CH XI itself says about it. His discussion of “the psychological conditions of the problem” (op. cit. 149-151) provides nothing of the sort; and his analysis on pp. 159-175 imposes a dualistic “static/dynamic” straitjacket on the Hermetica that obscures precisely the intermediary nature of aiōn as a “third kind.”

- In CH XIII, we read how the pupil Tat in fact “becomes the aiōn” and thereby achieves the state of expanded consciousness described as a theoretical possibility in CH XI: “Father! I no longer picture reality by means of my eyes but through the noetic energy that comes from the powers. … I am in heaven, on earth, in water, in the air; I am in animals, in plants; in the womb, before the womb, after the womb; everywhere … Father, I see the All, and I see myself in the Nous!” (CH XIII 11, 13). Detailed analysis in Hanegraaff, Hermetic Spirituality, Chapter Eight).

- Since we cannot assume that the text means to say there is nothing beyond the cosmos, not even God or his nous, I interpret this as a question about the nature of “being” along the lines of what we find for instance in Iamblichus, Response to Porphyry I 8 (see Réponse à Porphyre, 20-21): the realm of the gods cannot be enveloped by being – it must be the other way around.

- CH XI 18-20. Cf. HD V 1 (Mahé, Hermès Trismégiste, vol. 5, 230-231): “the nous sees everything” whereas the eyes see only corporeal things. It is not that the eyes allow the nous to see, but rather that the nous allows the eyes to see reality as it truly is. Hence this is not about rejecting the senses but about using them noetically.

- The ability “to make far off things present” through the imagination was an important aspect of nous since as far back as Homer (see von Fritz, “Νοῦς and νοεῖν,” 91; “Νοῦς and νοεῖν, and their Derivates, Pt. I,” 224 with note 10, 225, 239).

- Scott, Hermetica, vol. I, 21 (“become eternal”); Copenhaver, Hermetica, 41 (“become eternity”); Salaman et alii, The Way of Hermes, 57 (idem); van den Broek & Quispel, Hermetische Geschriften, 146 (“word een eeuwig wezen”: “become an eternal being”). Only Nock & Festugière, Hermès Trismégiste, vol. I, 155 has “deviens Aiôn” (but see ibid., 164 note 58: “Ou: deviens éternité,” followed by references to the Papyri Graecae Magicae that I consider irrelevant to the meaning of aiōn in CH XI); and Colpe & Holzhausen, Corpus Hermeticum Deutsch, 134 has “werde zum Aion.”

- Von Leyden, “Time, Number, and Eternity,” 36-37 (with reference to Simplicius).

- Ibid., 37-38.

- Castoriadis, “Discovery of the Imagination,” 244. See also reference above, note 12, and consider the remarkable statement in HD VI 1 (Mahé, Hermès Trismégiste, vol. 5, 234-235): “humanity’s creation is the world; if there were nobody to see [the world], neither would he truly exist, nor that which is seen” (whereas Mahé and van den Broek here choose to translate the Armenian stac ‘uac as “possession” [κτῆσις] instead of “creation” [κτίσις], I suggest that this latter option results in a much more logical statement). See also HD VIII 6 (Mahé, o.c., 256-257) “Everything came into being for you”; IX 2 (Mahé, o.c., 262-263) “external things would not exist if there were no internal ones.” From the same perspective it is tempting to speculate about the possible relevance of SH X, about the nature of time (see the very useful footnotes with source references in Litwa, Hermetica II, 67 note 2-3).

- See above, note 25.

- CH XI 17.

- Ascl. 17.

- SH IIA 3-4.

- I see this as an obvious reference to the “open sea” of ultimate beauty in Plato, Symp. 210d. Reitzenstein saw it as referring to der Himmelsozean in Mandaean and “gnostic” texts (Review of Scott [1927], 282 note 3); Festugière qualified this as “décidément fausse” (La révélation, vol. 4, 141 note 3) but provided no plausible alternative. To me it makes no sense to suggest that the author means just the normal sea (as in Nock & Festugière, Hermès Trismégiste, vol. 1, 156; Copenhaver, Hermetica, 42; Salaman et alii, Way of Hermes, 58; Colpe & Holzhausen, Corpus Hermeticum Deutsch, 135; van den Broek & Quispel, Hermetische Geschriften, 147). Note that Mahé draws close connections between the aiōn and the Egyptian Noun, described as “the original ocean” of being (“La création,” 23-24, cf. 29; referring to Morenz, La religion égyptienne, e.g. 222).

- Quispel imposes a reincarnational reading on the text (van den Broek & Quispel, Hermetische Geschriften, 147); Holzhausen sees a parallel to the well-known “gnostic” passage from Clement, Exc. ex. Theod. 78 (Colpe & Holzhausen, Corpus Hermeticum Deutsch, 135 note 383). I see neither of those interpretation as obvious, since the statement refers to the soul’s transcendence of temporality (“before you were born, in the womb, young, old, dead, in the hereafter”).

- CH XI 21.

- On the importance of negative passions in Hermetic spirituality, see Hanegraaff, Hermetic Spirituality, Chapter Six.

- Heidegger, Was heisst Denken?, 213-214 (my translation, with transliteration of the Greek terms; cf. Heidegger, What is called Thinking?, 210-211). Heidegger’s argument is based on his analysis of a famous formulation by Parmenides χρὴ τὸ λέγειν τε νοεῖν τ ᾽ἐὸν ἔμμεναι (Mansfeld & Primavesi, Die Vorsokratiker, 322, frg. 9). Note that according to Heidegger, thinking never gets farther from its original meaning than “when it gets the idea that thinking must begin with doubting” (Heidegger, op. cit., 214). This remark is of course directed at Descartes and suggests a perspective similar to what we find in the Hermetica: knowledge consists rather in a revelation or disclosure of true being. Heidegger’s basic point is confirmed by von Fritz: “Hellenistic philosophy replaced the contrast between νοῦς and αἴσθησις, which is characteristic of the latest stage of pre-Socratic philosophy, by the contrast of λόγος and αἴσθησις” (“Νοῦς and νοεῖν, and their Derivates,” Pt. II,” 32). Heidegger also notes, correctly, that investigating the meaning of logos and nous means questioning the very foundations of Western thought. See e.g. Was heisst Denken?, 182-183, 199, 207-208 (against those who think such questions to be eccentric or useless, he points out that without λέγειν and λόγος and what these words signify, we would have had no Christian trinitarian speculation, no modern technology, no Age of Enlightenment, no dialectical materialism, and so on: “the world would look different without the λόγος of logic”).