Adrián Navigante

TRANSVERSALITY: QUESTIONS OF METHOD

In this essay, Adrián Navigante reflects on a method that has been a guiding thread in the activities of the domain of Research and Intellectual Dialogue: transversality. This method appears as a possible reorientation in thinking and experience in the face of the state of knowledge, the cultural crisis, and the global challenges of the XXI century. Its potential and risks are related with the inevitable task of transforming our attitude to the world, as Alain Daniélou declared in his book Shiva and Dionysus, not only on the level of representation but mainly as a reeducation of perception, sensitivity, and relation.

Jean-Paul Sartre and the cover of his book Critique de la Raison Dialectique, published in 1960. Source: youtube channel “Rien ne veut rien dire” (program Les nouveaux chemins de la connaissance, 16 July 2013).

Jean-Paul Sartre and the cover of his book Critique de la Raison Dialectique, published in 1960. Source: youtube channel “Rien ne veut rien dire” (program Les nouveaux chemins de la connaissance, 16 July 2013).Introduction: Humus and Horizon

When it comes to defining ‘questions of method’, it is difficult not to think of Jean-Paul Sartre. The first part of his monumental Critique de la raison dialectique (1960) bears that title1 and relates it to the task of facing the challenges of the cultural horizon of his time – a horizon which, for many Westerners, remains a universal paradigm even today. It aims at the best possible articulation of life, thought, and action in a social milieu. Sartre’s explicit elucidation of the ‘method’ is, as the Greek word méthodos indicates, a pursuit of the right knowledge, in this case a path pointing to the relationship between humus and horizon, or between the soil from which a whole conception will grow and the consequences of the latter in the dynamics of the culture affected by it. In the case of Sartre, the questions of method intend to cover the complex passage from the contingency of subjective and objective circumstances to the necessity of an integrated totality of experience and knowledge, or to put it more simply: between a given situation and a process through which the ‘given’ is transformed. In this sense, Questions of Method points to a double movement toward knowledge and being which at the same time rejects their ontological separation: knowledge is ultimately no spiritual abstraction and being is no blind material substrate. Their synthetic confluence presents itself as a totalizing movement which resituates individuals and circumstances (with all the conflicts that their coming together presupposes) within an all-encompassing dynamic of meaning-fulness – a disclosure of ‘meaning’ as historical declension of ‘fullness’2.

What kind of ‘work of the spirit’ is capable of such achievement? For Sartre the task does not consist in grasping something that is already given and remains unchanged, but rather in realizing or – as said above – transforming subjects and circumstances toward that ontological and historically relevant confluence. This implies the passage from a static to a dynamic world configuration, which Sartre attempts to summarize taking the history of philosophy as paradigmatic example. Before European Enlightenment, the ultimate object of knowledge was totalizing but static – therefore it remained, strictly speaking, a property of theological thinking. After Enlightenment, the objective Spirit (God) could only survive “in the form of a regulative idea pointing to an infinite task”3. The Kantian critique enabled philosophy to get rid of an outdated ambition of totality – i.e. the rather simplistic concretion of metaphysical thinking in dogmatic statements. However, that important step did not lead to the rise of an emancipated humanity, but to that of a dominant class – the bourgeoisie – which naturalized its own relationship to the world to the detriment of the other social groups. The broadest totalization in philosophy was brought about by Hegel, in whose system “knowledge [was] elevated to its most eminent dignity”. In this framework, being was no longer known from the outside; instead, knowledge took hold of it and dissolved its opacity. In Hegelian dialectics, “the spirit objectifies itself, alienates itself and permanently recaptures its course; it realizes itself through its own history”4.

According to Sartre, the afore-mentioned movement can only be deemed ‘concrete’ if we keep in mind that there is an “unsurpassable opacity”5 at the core of individual experience. This is the point where Sartre comes back to Kierkegaard to justify the limited space and function of existentialism in a (Hegelian) world-conception that intends to concretize a totalizing movement: “whatever one can say and think of suffering, the latter escapes knowledge insofar as it is suffered in and by itself, so that knowledge remains incapable of any transformation on that level”6. The passionate intransigence of immediate life, the pure subjectivity that remains untransformed by the objective expression of the Idea (in Hegelian terms: the passage of God from being to becoming, or from eternity to history) turns out to be a mirror of infinity, an inner mirror reflecting the co-incidence of the tiniest with the greatest. This mirror accepts no mediation. If it did, it could be surmounted and classified – and therefore rendered ‘finite’, provincial, all-too-human. On the contrary, the qualitative leap to faith proves to be insurmountable, singular and universal at the same time. The distance between the human individual and God is infinite but remains a direct channel of communication – a channel impermeable to any instance of mediation7.

At this point, the conflict between the soil of individual existence (the roots of which are found in the singularity of the human subject) and the horizon of universal objectification (the summit of which is embodied in the Hegelian notion of World-Spirit) finds its resolution by resorting to the dialectics of Karl Marx, who, according to Sartre, “imposes himself over Kierkegaard and Hegel, since he asserts with the first the specificity of human existence and, with the second, takes the concrete man in his objective reality”8. The Marxian homo laborans, which is the slave of history, transforms the world. The objective process of capitalistic accumulation endows him with consciousness, it enables the slave to become master of himself. Finally, the world is turned upside down by the self-conscious slave turned into the very subject and meaning of History. Society after a Marxist revolution would shine – at least in Sartre’s imagination – with the light of a post-historical éschaton, that is why the term ‘History’, once the local method becomes the universal content, needs to be written in capital letter. After Hegel and Marx, history is not a mere succession of events, but a pleromatic process at work.

Knowledge has reached a level in which totalization, even in its secular form, turns out to be too general, too abstract, and too vague to ensure the consistency of a plurality of fields in need of further and deeper inquiry.

Philosophy, contrary to what ordinary people think, is no abstruse discipline. In fact, cultural processes are the result of a long-term incorporation, digestion and, in many cases, ‘domestication’ of philosophical ideas. This means that such ideas are not only the conceptual expressions of a certain period but also a shaping force of reality; they have more incidence on our lives than we think. Sartre says that periods of philosophical creativity are few and far between9, and in that sense he is right. Creativity in philosophy means subversion, that is, underlying (or explicit) tension with already-established cultural parameters with the aim of re-tracing the path going from the soil of the given situation to the horizon of its acceptable possibilities. In such cases, shaping means deconstructing, sometimes dissolving, but also re-shaping. Non-creative philosophers, on the contrary, are agents of cultural homeostasis (some of them merged beyond recognition with the regional elites of ‘scientists’ or ‘scholars’). They operate with already-digested ideas to shape a continuity of social relations according to constitutive and regulative principles ensuring general consistency. Ordinary people carry out the ideas of these cultural agents with a higher or lower degree of consciousness, depending on their education, studies, self-reflection, and influences. They inherit the ‘naturalized situation’ and contribute – blindly in most cases, purposely in a few exceptions – to preserve its parameters. This means that an analysis of Sartre’s philosophical exemplification can give us a key to understand where we stand today with regard to those questions of method. My conviction is that we stand at a considerable distance from what he thought were the universal (counter-)parameters of ‘philosophical creation’, and that is the main reason why other questions of method should be raised and programmatically developed as a general orientation.

Post-Modernity as Underlayer: The Return of the Repressed

In his book The Postmodern Condition (1979), Jean-François Lyotard declares that “science has always been in conflict with narratives”10. This verdict must not exclusively be taken in the sense of the traditional opposition (known in Plato) between logos and mythos, but mainly in the sense of a unification of knowledge through a ‘meta-discourse’ of science. Only scientific trials are conducted in laboratories (the way rituals are conducted in temples), but the knowledge of science is communicated in and to the world. In this sense, there is no denying that science finds its own legitimation through something that accounts for its content and at the same time transcends its method, something that cannot be contained in the very epistemic equation: a narrative process. The narrative emanating from science is not any narrative, though. It must be a narrative of knowledge, so it cannot be other than philosophy – philosophy as a metadiscourse. The aim of philosophy in Lyotard’s ‘given situation’ is not only to legitimate but also to amplify the status of truth immanent to each special field of research in order to reach the whole extension of society. The classical function of philosophy is to justify, amplify and unify knowledge stemming from regional ontologies (biology, physics, sociology, psychology, etc.). It is precisely this paradigm of a meta-narrative (nurtured by its own previous designation: philosophy as ‘science of sciences’) that cannot survive the transformations brought about by the post-modern condition.

Although modern episteme gained the upper hand in the XVIII century, the metanarratives of the emancipated human subject (Kant), the realization of the Spirit in history (Hegel) and the total transformation of society (Marx) were attempts to consolidate a world configuration in which, even without God, a unified meaning is preserved and deployed as a collective promise of ‘fullness’. The postmodern, says Lyotard, “is incredulous in the face of such metanarratives”11. Knowledge has reached a level in which totalization, even in its secular form (as thematized by Sartre), turns out to be too general, too abstract, and too vague to ensure the consistency of a plurality of fields in need of further and deeper inquiry: “The obsolescence of the metanarrative device of legitimation is paired with the crisis of metaphysical philosophy and that of the institution that depended on it”12. Knowledge cannot be totalizing any longer; on the contrary, “it refines our sensitivity to differences and reinforces our capacity to bear the incommensurable”13.

Lola Álvarez Bravo. Hilados del Norte 1 (circa 1944), a work displaying a perspectivist view of overwhelming urban processes of late modernity. Akland Art Museum. Source: México Moderno. Vanguardia y Revolución, Buenos Aires 2018.

Lola Álvarez Bravo. Hilados del Norte 1 (circa 1944), a work displaying a perspectivist view of overwhelming urban processes of late modernity. Akland Art Museum. Source: México Moderno. Vanguardia y Revolución, Buenos Aires 2018.Like Sartre’s Questions of Method, Lyotard declares that his essay is “a writing of circumstance [un écrit de circonstance]”14. Therefore, it is not a mere declaration but a diagnosis of his time. Ten years before the collapse of the Soviet Union, the French philosopher of post-modernity anticipated the total fragmentation of knowledge – which was already taking place and turned out to be the reverse-side of the last (quite degraded but highly effective) form of imperialist cohesion: the global expansion of finance capitalism15. Sartre’s radical prescriptions, such as that of the retrograde character of all anti-Marxist ideas or the reactionary character of plurality16, are rendered obsolete by Lyotard’s argumentation. The challenge is not any longer unification, universalization, and prescriptive truth, but de-centered cohesion, plural cohabitation (not always harmonious) and (agonistic) articulation of different narratives. With Lyotard, the utopian solution related to the bridge or the link between knowledge and social life is replaced by a pragmatic one. What is the positive side of it? Mainly the innovative reading (and denunciation) of the essential relationship between scientific knowledge and narrative emplacement as a form of concealed (or disguised) cultural imperialism. From this perspective, there is not much difference between a Christian mission bible-bashing to death indigenous populations in South America, an enlightened French humanist stifling a black insurrection in Haiti, and a Soviet militant destroying shamanic communities in Siberia.

Progressive de-legitimation of sciences – in the sense of an abandonment of metanarratives – implies, according to Lyotard, above all interdisciplinary work: “the valorization of team-work is related to the prevalence of a performative criterion of knowledge”17. In this sense, the focus on a plurality of disciplines must bear in mind a dialogical operation whose mediating instance does not step back from paradoxes. The logos of post-modernity is too open and fluid to accept the old chains related to classical standards of logic and rationality, since the consistency of representation is to a great extent an operation of power and dominance, and the plurality of views flowing beyond every prescriptive border intrinsically deconstructs the configuration of a homogeneous and well-delimited mainstream. This operation has consequences that go far beyond what Lyotard thematizes in The Postmodern Condition. In his considerations on ‘paralogy’ (which forms the last chapter of his book), we find an enigmatic sentence: “The little narrative remains the quintessential form adopted by the imaginative invention, foremostly in science”18. If the term ‘paralogy’ is to be taken as an argumentative register that transgresses the norms of valid reasoning, ‘imaginative invention’ is an expression that reinforces the access to another way of configuring the world. Lyotard seems to affirm the following: there is a passage from paralogy to paralogic in the sense of ‘working on paradoxes’. In other words, if the only totalizing instance of the post-modern period is that of an expanding ‘crisis’ (crisis of knowledge, crisis of justification of knowledge and action, crisis of valuable social links, crisis of authority, crisis of dialogical capacity, etc.), there is an increasing vitality of small narratives working everywhere locally and reshaping segments of reality beyond generally accepted parameters. Can this tension be resolved in any other way than by means of a sublation of all different cultural registers – whatever their provenance – in the unifying (and leveling) power of the global financial system?

In his introduction to the English version of The Postmodern Condition, Fredric Jameson takes “a further step that Lyotard seems unwilling to do”, namely “to posit, not the disappearance of the great master-narratives, but their passage underground as it were, their continuing but unconscious effectivity”19. Reading the obsolete metanarratives of history (mainly Hegelianism and Marxism) as unconscious determinants does not seem a step forward but rather backward. It turns out to be as regressive as the postulate that obsolete systems should be totally buried and in no way borne in mind when it comes to evaluating the present. The movement of digging out deeper layers should not reinstate mainstream tendencies of former periods, but rather disclose the real symptom of what is called European culture: that which pulsated underneath the conquering logos of its own universalization process. The unconscious is not only political, but also socio-cultural, ecstatic, collective, life-world and cosmic related, multiple and perspectivist in its own auto-póiesis. It is not trapped in a biological or sociological or historical evolution, it is not confined to the selectivity of a single cultural complex that has declared itself the only one valid and subjugated the existing ontological diversity to fit its own exclusive and unequivocal world-configuration. It is in those deepest layers that the terminological difference between ‘European’ and ‘Western’ finds its intrinsic link: the West is Europe’s horizon, or the survival of the European humus (basically Christianity and Enlightenment) in the minds of the conquered and assimilated. This link is of course not devoid of tensions, like those between the USA and Europe at present.

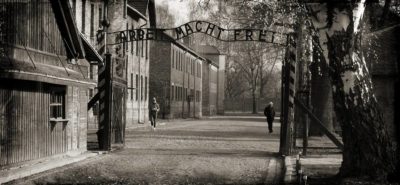

For Lyotard, post-modernity dissolves metanarratives and brings up the challenge of a plurality of logoi impossible to sublate. But even further: it discloses the return of the repressed. Is there any ‘image’ for what lies behind the paradoxes of European metanarratives? Lyotard reaches the deepest layer of the Western humus in his interpretation of the Shoah. In his book Heidegger and ‘the jews’ (1988), he thematizes the original repression (by means of the Freudian concept of Ur-Verdrängung) of a culture that promised a totalization of knowledge and an expansion of universal values only to end in the worst catastrophe of modern times: Nazism as the invention of a biological particularity (the Aryan race) elevated to a soteriological imperative (Europe’s salvation from both Soviet communism and American liberalism) demanding the emplacement of a politics of imperialist war and racial extermination. The fact that the allied ‘democracies’ were against German expansionism does not necessarily mean that they cared so much about the extermination of the Jews20. Lyotard is therefore right in writing ‘the jews’ without capital letters, “to make it clear that I am not thinking about a nation”, and in the plural, “to mean that I am not presenting any […] political subject (Zionism) or religion (Judaism) or philosophy (Hebrew thought) under that name”21. Lyotard’s ‘jews’ are a subtractive object: inconsistent, unreachable, symptomatically expelled from every field – of identity and difference, of being and becoming. Heidegger’s ontological difference could not reach them. They are a non-figure that pulsates beyond any representative formation and can never be grasped, not even as something that was erased the moment it took place. Lyotard refers to a multiplicity whose inconsistency forces the powers of dominance and expansion to perpetual (and sterile) attempts to cover that hole. In this sense, the reflection on the Shoah is for Lyotard the external border of every attempt to consolidate Western culture in terms of consistent identity. I will leave the moral question aside (since it would demand a long excursus) and concentrate on the transformation in Western thought that the XX century brought about, especially after the fall of all totalizing metanarratives. Post-modernity as the return of the repressed is the step beyond the conviction that there is an evolution, an expansion, a consolidation, a progress, and a differentiation carried out by the West for the sake of mankind.

The Rebooting ‘Flip-Side’: Strategies of Othering

Fredric Jameson’s strategy persists. The Hegelian-Marxist complex is tempting because it explains quite clearly (and critically) the functioning of Western society through history, but this temptation should be resisted the moment the conceptual complex takes that functioning as an absolute parameter for all civilizations. This happens mainly because there is an irrational fear of (heterogenous) multiplicity lying behind those constructs. For this reason, religious people think that only a ‘transcendent One’ can guarantee their salvation after death, and secular people demand the existence and intervention of a ‘welfare State’. If the disappearance of metanarratives (which ultimately guarantee ‘the One’ behind the multiplicity, the homogenous sublating heterogeneity) is a fact in the light of history, nothing guarantees that the consistency of such metanarratives should survive a descent to the waters of the Acheron. Following Jameson’s fashion, one can always resort to ‘unconscious layers’ as the unseen (i.e. underlying) horizon, but as I pointed above, the risk is to mistake unconscious layers with defense mechanisms. In that case, the work of the Spirit would keep blocking the disclosure of the repressed – it would perpetuate the symptom. If there is a reverse-side of the light of history, it is highly improbable that it should preserve the logic of what dominated its surface in the previous historical paradigm. To put the matter more clearly: if post-modern knowledge dissolves a metanarrative of universally valid cultural parameters based on the ‘high culture’ of the West, neither Hegelian nor Marxist (and let alone Christian) references will help in grasping either the cultural complexity of non-Western cultures nor the internal contradictions and ‘barbaric’ features within that so-called ‘high culture’. To understand the other(s) does not mean merely to describe their ways of behaving (as ethnographers do) but mainly to question our own assumptions as to what a legitimate point of departure in a process of (mutual) understanding really is. The assumption of a political unconscious is therefore the last defense mechanism to preserve an old strategy of local cohesion (Europe, the West) in which the local still believes that all the others (or otherwise localized) are mirrors of that specific locality22.

The challenge is not any longer unification of knowledge and prescriptive truth, but de-centered cohesion, plural cohabitation (not always harmonious) and (agonistic) articulation of different narratives legitimating knowledge.

Auschwitz, paradoxical symbol of what defies every instance of representation: the bottomless pit of Western civilization. Source: Public Domain Pictures Net (publicdomainpictures.net).

Auschwitz, paradoxical symbol of what defies every instance of representation: the bottomless pit of Western civilization. Source: Public Domain Pictures Net (publicdomainpictures.net).If we decide to cancel the defense mechanism that claims an unconscious survival of metanarratives, this action will certainly not lead to the disappearance of such totalizing discourses from the face of the earth. However, their validity will be for the first time relativized in a way that allows us to move on – not precisely along the line of the ‘(old) work of the Spirit’ but rather toward a (renewed) work on spirits. Where are those spirits? The irruption of the postmodern showed quite clearly that beneath each homogeneous construct of modernity – however solid it might seem – there is permeable soil connecting with subterranean contents and meanings that challenge the solidity of what is taken to be ‘the ground floor’ of our cultural building. The black pit thematized by Lyotard in Heidegger and ‘the jews’ is an epochal closing. Semitic culture appears as the external limit of a Europe claiming homogeneity, but the historical incursions of Western power opened other channels that now come back in the in-between places of the colonial palimpsest. If we move the eye away from the unifying strategy of Christianity (with its transcendent God and its desacralization of Nature) and the heritage of the Enlightenment (with its eschatological superordinate translated into progress and emancipation), many other spirits appear: South Asian, African, Amerindian, Australian, Siberian, etc. These spirits can barely be subsumed within a protraction of Western culture (as was intended in the past with categories like Indo-European culture or – even more boldly – Universal Self Consciousness mysticism). They impose themselves with their own specificity ever since anthropology made a decisive detour and replaced its former alliance with colonial power by a new attitude toward the other(s) based on unprejudiced understanding.

Of course, one could always say that non-Western cultures, even those which could not be – well or badly – assimilated to our ‘universal parameters’ (like China, Persia and India), do have their own metanarratives, sometimes orally transmitted (like the complex mythology of Indigenous peoples), sometimes contained in oracular patterns (after all, Ifa divination is as complex and elaborated as the revered and ever popularized Yjing), but the point is not whether they have or not a meta-structure of cohesion; it is rather the epistemological and ontological results of the enactment of those narratives. They don’t unify meaning towards the homogeneous superordinate that characterized modern rationality in the West. They don’t define nature as a self-contained sphere of inanimate objects, nor do they consider that human beings are the only entities endowed with interiority; they don’t think that events are better explained by their causes, nor do they experience time as something that passes and space as something we (as material bodies) merely occupy; they don’t possess universal truths to be disseminated, nor do they think that the earth obliterates the dead. Judged from our own world-configuration, they push us to renounce many taken-for-granted assumptions about reality and relations. They show us that beyond all our conscious efforts (in the name of progress) and our defense mechanisms (to preserve the superiority of the West) and our collective shadow (to impose our worldview for the good even at the price of extermination), there is a reverse-side, or perhaps I should say a flip-side23. The hole of the (absolute) ‘other’ is not merely a subtractive impossibility. It is a gate toward new epistemological and ontological challenges that Western culture should assume instead of clinging to outdated (and counter-productive) strategies of survival. If there is a form of ‘humanism’ to defend at this point, it is a form in which the utterly external and extraneous, so challenging or threatening as it may be, can have a place among the conditions under which we ‘see’ (i.e. experience) things in order to configure a world and describe the world(s) of others. It is no longer a question of integration, but of rebooting the hermeneutic machine, beginning with our own position.

Working on that flip-side implies changing our strategies of ‘othering’. This is the most difficult thing, because the ‘other’ is per definitionem external to a well-demarcated identity territory, which we identify with our ‘self’. Saying that the ‘self’ is a construction does not mean denying its value. It means introducing a degree of relativity in it, and the degree of relativity grows according to the cultural dynamics we are faced with. The cultural dynamics of globalization is in this sense a major challenge because it inserts the ‘other’ within the very foundations of the ‘self’ and at the same time seeks to erase all differences by resorting to the quantitative homogenization of ‘the market’ (the place of unlimited exchange and potential realization of needs and desires). This is the promise of its metanarrative, but it is not necessary to be a philosopher to realize that the dissolution of borders offered by the market is precisely the opposite of that old (Christian) utopia of a unified mankind – which also had its sinister consequences along its ‘historical realization’. The subversive power of the Post-modern is the capacity to create micropolitics of difference and alternative cartographies of desire. The danger is that if fragmentation remains a spontaneous reaction against homogenization, it may end up being swallowed by it without even noticing. From the proliferation of the myriad forms of new-age spirituality, there is practically no single movement that critically reflects on a differential work on the spirits (of the ‘others’). They fall very rapidly into full identification with old traditions or into a fully emancipated individual invention. In most cases, both end up being market products instead of cultural alternatives to the crisis of our time.

Transpiring Invisibility: Toward a Transversal Reorientation of Experience

What does this ‘alternative othering’ look like? Historians of religion like Jeffrey Kripal (a rare specimen in the field) try to incorporate the effects of radical differential experiences within Western culture into the very ontological conditions of the social construction of meaning. His methodological intervention contributes to a relativization of what were thought to be absolute parameters of understanding and defining ‘reality’. The interesting thing is that he reconstructs alternative movements within Western culture, not only in poetry and literature (from William Blake to Evelyne Underhill24) but also in the field of scholarship (from Frederic Myers to Jacques Vallée25), working at the margins of the dominant epistemology to relativize its effects. There is still the temptation, and that is an undeniable aspect of Jeffrey Kripal, to link the epistemologically subversive methodology he introduced in the field of religious studies with a ‘mystical model’ independent of any culture – which can be easily brought back to Western strategies of assimilation instead of alternative strategies of othering. Kripal’s transgressive bent in his definition of “the knowledge of such a [subversive] historian of religions as “a kind of gnosis”26 is very inspiring if taken as an expansion of scholarly research into the hidden (or repressed) side of receptivity, imagination, and insight within intellectual production – precisely because such procedure takes reflexivity to a point of reversal and the dominant epistemology of modernity to a point of internal fracture. But it can end up being reductive if it does not bear in mind that every relativization of mainstream parameters needs to be located and its location cannot be the dominant emplacement of ‘universality’ (whether Christian, secular, or non-dual). The local articulations of the flip-side are much more interesting and cohesive than any potential relapse into strategies of unification that end up replacing the dualism of modern Western ontology (self/other, subject/object, mind/body, imaginary/real, etc.) by a non-dualism that looks more like a ‘naturalized substratum’ (after the fashion of traditional metaphysics) than like the ontologically dynamic ‘between-ness’ required – by the very context of our crisis – for new strategies of ‘othering’27. Working on the spirits of the others, that is, on the paralogical or paradoxical incorporation of radically different modes of thinking and being into our social and ontological scaffolding, is betting not only on the postulate of a flip-side but also on the articulation of it without confining local cartographies to epistemological invisibility. The best way to do justice to the ‘other’ is not by pasting it on the smooth skin-surface of our ‘self’, but rather by letting it transpire through the tiny pores of one’s own cultural defense shield.

A very significant example of alternative othering is provided by post-structuralist anthropology, out of which arose the very controversial but also fruitful expression ‘ontological turn’28. When (and how) does anthropology take this turn? Eduardo Kohn provides a useful answer to this question: “I define ontological anthropology as the nonreductive ethnographic exploration of realities that are not necessarily socially constructed in ways that allow us to do conceptual work with them”29. That the anthropological exploration of other realities may end up questioning the basic assumptions of the ones describing those realities is something that anthropology has known since its very beginning. That the experienced disparity may challenge those assumptions to the point of compelling the anthropologist to re-configure his/her ‘reality’ against the inherited ‘soil’ of experience and intellection is something quite different. Normally anthropologists are willing to modify their horizon of expectation for the sake of the discipline, but not the (pre-reflective) soil of their own methodological assumptions. In the last case, the reality of the ‘other’ ceases to be an object of research and becomes a non-objectifiable living perspective displaying a retroactive effect on the ‘self’ of the observer; it turns each one of the latter’s own analytical and even existential resources upside down, and this may lead to sacrificing the discipline itself. In the face of this challenge, the two alternate solutions in the history of anthropology have been to reject it, partially or altogether (as has been the case with missionaries, colonial agents, and ethnocentric scholars – even in the post-colonial period), or to emphatically identify oneself with it (like certain heterodox authors who decided to take a jump off the rational edge and ‘go native’). Utter rejection of the challenge of the other is simplistic and retrograde; one-sided identification can be fascinating and sometimes arduous – but still proves to be insufficient when it comes to facing the challenge. Another kind of response is demanded, based on a transformation of the basic ‘questions of method’ (including the – positive or negative – projection mechanisms at work in the attempt to ‘grasp’ the other) in order to hold the insurmountable tension of opposites30. What is required to face this challenge and do justice to its complexity is a transversal (re-)orientation of experience.

The ungraspable aspect of the ‘other’ is a gate toward new epistemological and ontological challenges that Western culture should assume instead of clinging to outdated (and counter-productive) strategies of survival.

What does this transversal reorientation consist of? To begin with, it is a reorientation concerning the method. The mechanics of globalization demands a transcultural response, in the sense that each culture is permanently addressed and challenged by ‘external agents’ in a way that the latter are reinserted within the immanence of the affected identity. This is especially the case in the West, which is forced to assume, for the first time in his self-contained history, the relativization of its own ‘universal’ parameters also from within – or in social terms: a progressive hybridization of its ‘soil’. A proper reorientation in method should not only accept the fact that the reflexivity of Western thought can no longer reject the ‘ethnological input’ leading to its own ontological relativization. But there is a further step to take. The moment the ‘other’ ceases to be a (straight or inverted) mirror of our ‘self’, this ‘self’ immediately ceases to be the fundamentum we thought it to be, and many instances of difference and otherness become visible. The ontological relativity of mainstream Western principles and values should not be confined to the challenges of anthropology, such as the consideration of animistic cosmologies as examples of an instructive phenomenology of relations31 or the revalorization of the totemic imagination as narrative device of (de-centered) local resistance in the face of capitalist deterritorialization32. There is also an internal critique to carry out because difference and otherness are not only part of an external landscape; they constitute our internal dynamics. A transversal reorientation is a learning process, a reeducation of our perception and cognition, a modification of our being-in-the-world. We can reeducate our mode of thinking with critical training, but the register of critique will tend to remain fixed on the very soil that constitutes our hegemonies of representation. We can criticize a political system, the application of a law, the uses and abuses of science and technique, discrimination and racism, or the distribution of wealth in the world. Our hegemony of representation remains nonetheless intact. Quite different is to question the fact that only humans have an interiority, that is, to ascribe a soul or a spirit to animals and plants – certainly not metaphorically but in concrete interaction with them –, or to say that nature as a self-contained domain of objects does not exist, or affirm that the difference between the different actors in the chain of being does not lie in their substantial constituents but in their body’s capacities to be affected by other bodies – the body being in this case a fluid and perspectivist energy quantum disclosing world(s). This is the input of ethnology. But this input has been the whole time among us, in the undercurrents of Western culture. It suffices to think about visionary poetry and esoteric thinking. After all, what is the alchemical experiment of Michael Maier, what are the mythological effusions of William Blake, or Antonin Artaud’s theater of cruelty? They are not merely three imaginary attempts at restitution of a cultural horizon in periods of collective disintegration (the Thirty Years’ War in the case of Maier, the French Revolution in Blake, and the collapse of Europe between the two world wars in Artaud33) but rather a way of questioning the very soil that led that culture to experience such convulsions. They attempted to re-shape the coordinates of world-relation in periods of increasingly reductive monoculturalism, but their work will never become visible if we don’t re-read it from another viewpoint than that of the self-sufficient critic whose assumptions about ‘elucidation’, ‘contextualization’ and ‘solid argumentation’ remain intact before and after confrontation with those authors.

University of California Publications in American Archeology and Ethnology (1903). Berkeley University of California Press. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

University of California Publications in American Archeology and Ethnology (1903). Berkeley University of California Press. Source: Wikimedia Commons.Conclusion: Transversality as ‘Balancing Act on a Hanging Bridge’

Just as critics do not venture into the world of poets, anthropological knowledge, as useful and sometimes challenging as it may be to question deep-rooted assumptions about the value of other modes of living, tends to set a limit to its own reflexivity, precisely at the point where the main presuppositions of the discipline are threatened by the analytical reversal that other cosmologies and social practices demand. This step back is ‘reassuring’ in two ways: it prevents an irrational ‘flight from reason’ (going native), and it reinstates the scholar in a position of power that is not only related to his own institutional status but to a hegemonic constitution of reality. One can describe the other, in detail and even sympathetically, but ultimately one cannot act out the other. The other remains a representational object – however scrutinized, appreciated and recognized it may be. The skepticism related to a possible permeability of the method has a clear counterpart in the skepsis with which most anthropologists react if they are asked to venture an extension of their theoretical assemblages beyond their ‘objective descriptions’34.

A transversal reorientation does not consist in thinking differently while keeping hegemonic presuppositions intact. It does not mean discarding everything related to the inherited world-configuration, either, since that is utterly impossible, even in the most radical cases. Reorientation means challenging the soil, opening the gaze, reshaping the horizon in both directions: learning from the ‘other’ on the level in which objectification ceases, deconstructing the ‘self’ accordingly, but at the same time re-shaping the ‘self of the other’ through the inevitable distance being bridged over (which is not without tensions and conflicts) and nurturing an ‘internal other’ within ourselves. The transversal reorientation is an in-between, a work of interstices, and at this early stage it can be compared to a balancing act on a hanging bridge whose anchorage, deck and ropes are distressingly unsteady. Transversality35 is in this sense a very daring act with no guarantee of success, but in the present context and given the serious challenges that humanity is facing, it is necessary. It is also the method philosophy should adopt to deal with such issues, since philosophy is almost by definition a transversal way of thinking – partially coupled with science, partially coupled with arts, but also independently enough to cut through both domains; closely related to life in order to embrace an ‘art of living’, but at the same time detached from the immediacy of the former to come up with judgements concerning one’s own actions; solidary with societal processes and experiences (of a religious, legal and political sort), but at the same time in rupture with them in questioning even the very basis on which they are built.

A philosophy based on a transversal reorientation in thinking would certainly not preserve the totalizing function that Jean-Paul Sartre ascribed to it. It would not limit itself to well-delineated rhetorical interventions for the sake of a social communication of specialized knowledge, either. The first task is too big, since the world is more than what almost thirty centuries of Western philosophy can summarize and sublate. The second too is limited, since in the post-modern and post-secular world knowledge is not only produced by the scientific and technical elites of Western culture – there are also forms of oracular knowledge, plant-based knowledge, trance-related knowledge, mystical-hermeneutical knowledge procedures, etc. Such modalities of knowing cannot be reduced, as in the colonial past, to a cabinet of curiosities, nor can they be taken at face value out of sheer fascination (the problem of superstition does not lie in the other but in the mechanisms of appropriation applied to the other’s universe). They need to be integrated into a progressive and thorough philosophy of world compossibility, with all the difficulties and promises that the construction and the exercise of such a philosophy implies.

- The title in the original French version, Questions de méthode, was translated into English as In Search of Method. For the purposes of my essay, I will maintain the literal translation ‘questions of method’.

- In spite of his declared atheism, Sartre’s movement adopts to a great extent Hegel’s historical ‘Theodicy’ as expounded in the latter’s Lectures on the Philosophy of History (1837), that is, it does not show much discontinuity with the Christian conception of revelation that Hegel intends to translate into a totalizing meaning of ‘world history’: “Our treatment of the subject [philosophy of History] is, in this aspect, a Theodicy, a justification of God, which Leibniz attempted in his own way on a metaphysical basis with indefinite and abstract categories, so that the ill found in the world may be comprehended and the thinking Spirit reconciled with the existing evil” (G. W. F. Hegel, Werke 12: Vorlesungen über die Philosophie der Geschichte, Frankfurt 1986, p. 28).

- Jean-Paul Sartre, Critique de la raison dialectique, Tome I, Paris 1985, p. 15.

- Jean-Paul Sartre, Ibidem, p. 22.

- Jean-Paul Sartre, Ibidem, p. 23, note 1.

- Jean-Paul Sartre, Ibidem, p. 23.

- Jean-Paul Sartre, Ibidem, p. 24.

- Jean-Paul Sartre, Ibidem, p. 26.

- “il est bien clair que les époques de création philosophique sont rares” (Jean-Paul Sartre, Ibidem, p. 21).

- Jean-François Lyotard, La condition postmoderne, Paris 1979, p. 7.

- Jean-François Lyotard, Ibidem.

- Jean-François Lyotard, Ibidem.

- Jean-François Lyotard, Ibidem, p. 8.

- Jean-François Lyotard, Ibidem.

- Lyotard takes as a point of departure of this historical phase the 1950s, which coincides with the achievement of Europe’s reconstruction after the World War II (cf. Jean-François Lyotard, Ibidem, p. 11).

- These two verdicts are easily deduced from his declaration of Marxism as the “unsurpassable philosophy of our time”, which means that there is no anti-Marxist argument that can possibly contribute to the progress of mankind and that the rejection of a totalizing reason capable of integrating plurality means a regression into provincial nodes of dogmatic thinking (cf. Jean-Paul Sartre, Critique de la raison dialectique, pp. 21 and 29, respectively).

- Jean-François Lyotard, La condition postmoderne, p. 86.

- Jean-François Lyotard, La condition postmoderne, p. 98.

- Fredric Jameson, Foreword to The Postmodern Condition, Manchester 1984, p. xii.

- In this respect, cf. Alain Badiou, Le siècle, Paris 2005, p. 15.

- Jean-François Lyotard, Heidegger et « les juifs », Paris 1988, p. 13.

- Of course, the locality is not always geo-political. It can also be implanted in the structure of thoughts and feelings of its carriers – especially in the so-called ‘global context’.

- The word ‘flip’ in the expression ‘flip-side’ intends to evoke, in this context, the promising effort of a historian of religion like Jeffrey Kripal to shake the foundations of scholarly rationality with a methodical procedure of intellectual transgression that does not in any way attempt to throw Western intellectual history overboard. His conception of ‘the flip’ is a clear illustration of what can go beyond ‘the hole’ of otherness in the West to extract new hermeneutical possibilities: “The moment of realization beyond all linear thought, beyond all language, beyond all belief, is what I call ‘the flip’ […]. The pages [of this book] attempt to flip the reader via story, philosophical argument, and simple human trust (in the otherwise-unbelievable stories that other human beings tell us here) […]. I begin by employing a set of common extraordinary experiences to call for a new recalibration of the humanities and the sciences toward some future form of knowledge” (Jeffrey Kripal, The Flip: Epiphanies of the Mind and the Future of Knowledge, New York 2019, pp. 12-13). If taken as an ethnology of abnormal (or counter-canonical) experiences within Western mainstream culture, his work is very valuable and needs to be collated with ethnological work on other cultures to build a new morphology of human and non-human relations.

- Cf. Jeffrey Kripal, Roads of Excess, Palaces of Wisdom: Eroticism and Reflexivity in the Study of Mysticism, Chicago and London 2001, especially his ‘Blakean-Tantric inversion of Freud’ (in the Introduction) and the epistemological complexities of ‘experience’ brought about by Underhill’s work (in chapter 1), which go in the direction of my argumentation.

- Cf. Jeffrey Kripal, Authors of the Impossible: The Paranormal and the Sacred, Chicago and London 2010, where he deals also with other authors like Bertrand Méheust (and by extension with William James, Gregory Bateson, Ernesto de Martino and C. G. Jung) and the science mysticism in the fantastic narrative of Charles Fort.

- Jeffrey Kripal, Roads of Excess, Palaces of Wisdom, p. 5.

- In this respect, a good example would be Terence Even’s approach to the “problems of otherness”, summarized thus: “Such defining ethnographic problems as what is the nature of kinship? Or how can there be order in society without government? or […] what is the sense of magico-religious presumptions? […] require for their resolution nothing less radical than ontological conversion” (Terence Even, Anthropology as Ethics: Nondualism and the Conduct of Sacrifice, Oxford and New York 2008, p. 3).

- The discussion literature on the question of the ontological turn in anthropology is vast and it is not the purpose of this essay to provide a thorough account of it. For a succinct reconstruction of the ontological turn in French anthropology see John D. Kelly, The Ontological Turn in French Philosophical Anthropology, in: HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory (4), 1, 2014, pp. 259-269; for a systematic evaluation of the anthropological turn outside of France, see Martin Holbraad and Morten Axel Pedersen, The Ontological Turn: An Anthropological Exposition, New York 2017.

- Eduardo Kohn, Anthropology of Ontologies, in: Donnald Brenneis and Karen Strier (eds.), Annual Review of Anthropology, Vol. 44, pp. 311-327, quote p. 315.

- It is usually argued that in multicultural societies there is no such ‘tension of opposites’, especially because many people stem from more than one provenance. Even when multiculturalism is a reality, and the ‘fluidified’ (inner and outer) boundaries of individuals and social groups contribute to a permanent re-shaping of the cultural landscape, there is always a construction of ‘self’ at work in relation to ‘other(s)’, and the modality of that relation is not devoid of tension (even within the same individual or group). In such cases, alternative strategies of othering are not only carried out in the outside world but also in the inner sphere of one’s own (apparent) ‘self’.

- Cf. Graham Harvey, Animism: Respecting the Living World, London 2019.

- Cf. Barbara Glowczewski, Rêves en colère. Alliances aborigènes dans le Nord-Ouest australien, Paris 2004.

- These attempts are not to be taken strictly speaking as chronological responses (Maier’s Atalanta Fugiens, for example, was composed on the eve of the Thirty Years’ War, as opposed to Blake’s visionary work, which is contemporary and posterior to the Reign of Terror), but rather as atmospheric or field-related reactions – anticipatory, contemporary, or retroactive – to their perception of an acute crisis; nor are they to be seen as successful attempts. Antonin Artaud’s Les nouvelles revelations de l’être, for example, is a kind of apocalyptic manifesto in which he sees unequalled flashes of insight on the catastrophes of the coming times. However, as late as in 1943, Artaud wrote a dedication to Hitler in one of the copies of that book. The failure of Artaud’s attempt does not really lie in his dedication to Hitler, but mainly in the effects of it, or more precisely in having provided the psychiatric power (in his case Dr. Gaston Ferdière) with the perfect excuse to re-interpret almost the whole of his poetic operations – from the mystical openings in content to the glossolalian rupture of discursive logic – as ‘madness’ (cf. Antonin Artaud, OEuvres Complètes VII, Paris 1982, pp. 423-424).

- A refreshing exception to this rule is Brazilian anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, whose work contains not only solid research and a philosophical elaboration of the ethnographic material obtained through local fieldwork and complementary readings of extensive ethnographic records, but also a political agenda to further the survival and interests of Amerindian peoples.

- My debt to Félix Guattari in the subject of transversality, far beyond the parameters of the field in which he mainly worked (alternative psychiatry), is something on which I will elaborate in a future essay.