Adrián Navigante

ALAIN DANIÉLOU: SACRIFICE AND COMPOSITION OF THE WHOLE

This essay was written for the second symposium on the question of Sacrifice organised by the Alain Daniélou Foundation in collaboration with the Association Recherches Mimétiques (ARM) in September 2020. Adrián Navigante’s reflection on Alain Daniélou’s conception of sacrifice began in 2019 within the framework of the seminar “Perspectives on Sacrifice” at the Bibliothèque Nationale François Mitterrand (BNF) in Paris, France; it has later been deepened and amplified beyond the Indian context to include Greek antiquity and Daniélou’s project of a ‘return to paganism’. This English version of this essay (originally written in French) has been slightly modified for Transcultural Dialogues.

Alain Daniélou at the Labyrinth around 1979. Photo by Jacques Cloarec

Alain Daniélou at the Labyrinth around 1979. Photo by Jacques CloarecTowards a diagonal of thought in the question of sacrifice

At the BNF symposium last year, I approached the question of sacrifice from Alain Daniélou’s perspective. To this purpose, my presentation was based on a reconstruction of the principal aspects defining a reading of sacrifice in Hindu tradition, particularly the tension between a reception of the Brahminic tradition in which Daniélou was ‘re-educated’ and a hermeneutic opening to Tantrism as a symptomatic deviation of Veda, that is, a revelation of certain repressed elements in the constitution of a mainstream culture. I now propose to consider Daniélou’s conception of sacrifice as ‘diagonal’ to the central discussion line of this symposium, which is the dialogue between Roberto Calasso and René Girard on the question of sacrifice. This dialogue poses the central question: is sacrifice part of an inevitable economy of creation in which increasing awareness of its inevitability and even ascetic reactions are included, or does the anthropological difference, especially through the Christian message of Christ’s passion, introduce the discontinuity of an inverted mimesis – reproducing ‘love’ instead of ‘violence’ – and the possibility of a radical change in that economy? This time I do not intend to approach this question from within the Indian tradition (as I did at the BNF), but by considering the tension between ‘paganism’ and ‘Christianity’ (a subject that permeates the debate between Calasso and Girard) in the Hellenistic world, revealing a somewhat wider horizon – closely related to the thought of the later Alain Daniélou on ancient Europe – that allows us to reread this tension in the current context.

Regarding the debate on sacrifice between Roberto Calasso and René Girard on the TV programme Océaniques in 1990, one is greatly tempted to take Calasso as the defender of a mythical system – linked to the pagan notion of the ‘sacred’ – against the voice of the Christian difference raised by Girard. Although it is not wrong to do so, this type of reading risks over-simplifying a subject that deserves wider and deeper consideration. I will therefore attempt to present another view, through which it will become clear that the paganism defended by Calasso rests on a modern conception (one might say an already-Christianised perspective1), and that Girard’s Christianity has a considerable value if it is limited to a specific context as an internal critique of it: the context of the European-Christian tradition.

In other words, I will not say – as Roberto Calasso said about René Girard at a conference held in 2009 at the Collège des Bernardins – that we are faced with one of the very rare church fathers of our time. I would rather say that Girard can be considered to have introduced a break with regard to that tradition. A book like Achever Clausewitz forces me to push my thought beyond the undeniable historical sympathies that may have inspired Calasso’s theory. In fact, the Christian message of apologists as a ‘call to conversion’, with their visceral denunciation of paganism2, is re-established and revivified in Girard’s demystification of pagan violence – as a form of violence exercised over innocent victims – and revelation of its component mechanisms. Reading Achever Clausewitz attentively, I understand that the ‘historical discontinuity’ of this demystification – which introduces its ‘eschatological link’ – coincides with the irruption of the ‘satanic’ in human history. The discontinuity in question is not a mere replacement of ‘violence’ with ‘love’, but at the same time an overflowing of violence – also in the name of love. At this point, another perspective is required to balance the opposite poles – a reading based on what I would call (returning to Daniélou) the ‘composition of the whole’.

Alain Daniélou’s ‘Return to Paganism’

In the history of ideas, it is well-known that so-called ‘returns’ (to a tradition or an author) are the result of a modification within a system of ideas according to criteria foreign to the context in question, highlighted by a singular appropriation from the past. If I were to mention three paradigmatic cases in French culture, the return to Marx carried out by Althusser, the return to Nietzsche undertaken by Foucault and the return to Freud elaborated by Lacan are not merely a movement back to, but the extraction of something not-seen and unthought-of that subverts the present and retroactively shapes the past. The same thing could be said, cum grano salis, of Daniélou’s ‘return to paganism’, of which I shall present a succinct conceptual sequence by way of introduction: 1. There is no return to paganism without a religion of Nature (his criticism of monotheism3); 2. There can be no religion of Nature without a change of perception and cognition of the real (his criticism of anthropocentrism and its related consequences4); 3. There can be no re-evaluation of the real without experience of the other5 resulting in a reconsideration of our own world-configuration (his criticism of globalism and egalitarianism6).

Sacrificial ceremony for Masto, an ancestral deity of the Khas people in Nepal. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Sacrificial ceremony for Masto, an ancestral deity of the Khas people in Nepal. Source: Wikimedia CommonsThis sequence shows that the ‘return to paganism’ to which Daniélou alludes is not some whimsical and purely individual project, but rather a significant detour from a process of cultural blindness. Such a return means classifying, ranking and distributing beings (human and non-human) without adopting the modern Western (Christian) assumption of a social order forged by humans (whose sphere of liberty can be ultimately traced back to God as Creator of the world) as opposed to the order of things (which would fall under the jurisdiction of necessity or of natural constraints). In this sense, the term ‘Nature’ is both appropriate and equivocal. Firstly, it tells us that Daniélou’s thought points to a conception of immanence in which even religion must have its place, since the roots of religion are not cut off from ‘manifestation’ – that is, from shared, collected and distributed experience. Such ‘open rooting’ [enracinement ouvert]is contrary to the idea that Nature is an order of strict causality and necessity, or even of an objectifiable totality opposed to the social order7. Secondly, Daniélou resorts to a (re-)sacralization of Nature – which is why I have given that term a capital letter. Sacralizing means de-objectifying the sphere in question to make a terrain of encounters and mysteries out of it – without however turning it into the inscrutable non-place of savage mysticism.

Let us say that, for Daniélou, non-European cultures (not only that of India8) show us that we never coincide with the humankind we believe ourselves to be, and that the awareness of this asymmetry (or non-identity) is the antidote against falling into deviating or excessive forms of domination, pillage and destruction9. The equivocal aspect of the term can be summarized as follows: by writing ‘Nature’ in capital letters, one always retains the possibility of underlying the ‘given’ or the ‘prime qualities’ to the point of making an ontological paradigm of the mystery out of it. This also means transforming paganism into a mystical impulse to merge with the deepest secret of surrounding reality – something exclusively revealed to the natives10. Although Daniélou’s thought remains attached to an idea of ‘the primordial’ as one of the keys to understanding the notion of the sacred and its relationship with sacrifice, I wish to present something more complex – and I hope also interesting – for discussion. Daniélou does not expound the conceptual couple ‘sacred-sacrifice’ either to show the relationship between transgression of the law and divine continuity (as Georges Bataille does)11, or to reveal a primitive ontology that binds us to the world of archetypes (like Mircea Eliade)12, but to remind us of the active composition of the whole that India has maintained in an exemplary manner and which can also be found in other cultures. He thus inverts René Girard’s understanding of the Christian paradox announced in Achever Clausewitz, which can be expressed in his own terms: we can all participate in Christ’s divinity, so long as we renounce our violence (meaning, according to Girard, the sacrificial trickery of old); however, we now know that humans will not renounce it (meaning that this trickery of old has the type of cultural relevance that is lacking today13). Daniélou’s inversion of this paradox is totally different from the position of Georges Bataille, with whom Daniélou has sometimes been compared. For Bataille, the paradox of Christianity consists in the desire to rediscover the continuity of being – which necessarily requires a transgression linked to violence and death – in the downward spiral of ritual actions towards a total and definitive elimination of violence. In other words: for Bataille, the apostolic transfiguration of existence into love (starting from the total synthesis of violence fully reversed and sublated in the person of Christ) shifts the continuity of the being (excess of life without conscious distinction) towards the sphere of discontinuity (egoism, calculation, alienation). The immediate – and, for Bataille, absurd – consequence of this shift is to view the sacred in the profane and imagine an immortality of discontinuous beings, an immortality totally cut off from the violence of animal life-excess and re-located in pneumatic individualities14.

Now, Daniélou appears to approach this problem differently. He compares Christ to Moses and Mohammed. He conceives the Christian message as an attempt at liberation from a dried-out, puritan and inhuman monotheism. Christ opposed the dominant religion of his time (that of the Roman Empire), as well as the collaborationism of the élites (Rabbinic Judaism). His teachings were addressed to the humble and marginal, the persecuted and the prostitutes15. Most important of all, however, his figure could not be severed from the pagan sources that had nourished it, particularly the Orphic mythology surrounding Dionysus16 and the idea of a community that participates otherwise in the order of Creation17. What Daniélou calls ‘the problem of Christianity’18 mostly concerns the history of Christ’s message – a logic of becoming coinciding with the distortion of his project: “Later Christianity is, in fact, diametrically opposed to it, with its religious imperialism, political role, wars, massacres, tortures, stakes, persecution of heretics […]Christianity thus became an instrument of conquest and world domination, just as Buddhism had been for the Indian emperors. This kind of activity has lasted down to our own times, causing the elimination of autochthonous cults and gods in Europe and the Middle East. Later on, this same activity spread over the whole world, depriving the various peoples of their gods and therefore of their power and personality. It reduced them to a state of moral and ritual dependence”19.

‘Return’ and ‘detour’: sacrifice, interdiction, integration

According to Daniélou, the history of Christianity is a distortion of Jesus’s project. But what is the origin and what was the nature of his project? In Shiva and Dionysus, we find allusions that seem too speculative, obscure and sometimes even scanty, but which are not at all lacking in meaning. Allusions such as the relationship of the original Christian message with Orphism should be specially borne in mind, since this relationship best expresses Daniélou’s position on what I have called, in the first part of this essay, ‘the Christian paradox’. I quote Daniélou: “In the West, Orphism inserted itself into Dionysism and perverted it. Orphism was an adaptation of Dionysism to suit Greek taste and corresponds to certain forms of Shivaism which were incorporated into Aryan Hinduism […]The influence of Jain thought can be felt”20. This means that, according to Daniélou, since the history of Christianity was a perversion of Jesus’s initial plan, the initial plan itself was linked to a perversion of Dionysism (Orpheus’s reform), in other words, to the ascetic and soteriological becoming of a cult that had originally integrated mankind with Nature in its entirety – as a composition of the whole. The comparison of Orphism and Jainism plays an important role, well beyond certain readings of Megasthenes that we can trace back in Daniélou21, since Jainism, with its doctrine of salvation (instead of ecstasy), ethics (instead of rites) and asceticism (instead of Eros), is in Daniélou’s eyes the opposite of Shaivism. Instead of integrating man with the other spheres of being (plants, animals, gods), it disengages and isolates him. One reason for this isolation is the rejection of blood sacrifice and whatever is connected with defilement. The same can be said of Orphism in comparison to the central elements of Dionysian religion (orgiastic, divine madness, sparagmós, homophagy).

Sacralizing means de-objectifying the sphere of Nature to make a terrain of encounters and mysteries out of it.

Here we reach a central point: Which symbolic and ritual aspects of the Dionysian cult are emphasized by Daniélou? The phallus, the serpent and the bull22. I would say this is not arbitrary. If we consider, for example, the proselytist strategies of Clement of Alexandria in his Protrepticus, we find that he does manipulate the value of these symbols, already when he uses the Biblical perspective to interpret pagan elements. According to Clement, the phallus is no longer the power of life, but the sexual organ23. The serpent is no longer doubly connected to the idea of fecundity (as regenerator of the earth) and to funeral rites (as the protector of tombs)24, but is uniquely attached to evil. The word ‘mystery’ is reduced – by forced etymology – to mysos (defilement)25 to underline that the birth and death of Dionysus are impure. But the question doesn’t stop there: far from it. This is the point at which it really becomes interesting. We realise that the impurity of the god’s birth26 has a function in the apologist’s anti-pagan plan (to set Dionysus-Orpheus against Christ), but the impurity of the god’s being put to death proves pertinent in a further relation between the Orphic Dionysus and Christ27. This relationship proves to be significant for the problem of sacrifice, since the Protrepticus shows the trace of a new religion starting from an almost imperceptible inversion which, at the same time, makes an essential difference. This inversion is carried out by mentioning Dionysus’s death at the hands of the Titans, an episode termed ‘midway’ between the sparagmós (dismemberment of living animals, linked to maenadism) and ritualised sacrifice (cutting of the flesh and placing it on the fire). Although the Titans use knife, fire, tripod and pot to cook their victim (alluding to the instance of cooking in the conventional sacrifice), first they boil him, then roast him28, instead of following the cooking-roasting sequence – which was the rule for any ritual murder since Homer29. This perversion of the culinary ritual may be read, not only as a criticism of ritual impiety, but as a proclamation of a much more radical detour: any sacrificial putting to death (whether formalized or not) would henceforth be considered a crime30. This latter aspect clearly shows that Orphism involves a purification of the religion of Dionysus as a religion of Nature (with an ontological permeability between animals, humans and gods) and, at the same time, a revolution in customs – since the codes of ritual and ethical prescriptions of Orphism insist on a maxim that Calasso summarises in his filmed debate with Girard as follows: apéchesthai tou phónou (abstain from killing)31. Some passages from Eratosthenes of Cyrene or Conon the mythographer32 confirm this change of paradigm: the allusion of replacing Dionysus with Apollo, or of forgetting to praise Dionysus when Orpheus, during his descent to Hades, celebrates the race of gods.

Roman Statue of Dionysus (between 117 – 138 CE). Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo Massimo. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Roman Statue of Dionysus (between 117 – 138 CE). Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo Massimo. Source: Wikimedia CommonsLet us return now to Alain Daniélou to clear up one central point: if Christianity was to become a distortion of Christ’s plan, can we say that Daniélou saw the possibility of including Christ’s plan – detached from its distortion – in the programme of a ‘return to paganism’? He seems to have considered the matter, but his response is negative. For Daniélou, the figure of Christ is inscribed in a pre-Christian context considerably distant from Jerusalem: a Christ relating to the Orphic Dionysus. In other words, Jesus, just like Orpheus, had the power of attracting beings (not only humans, but also non-humans)33 to him in order to reintegrate them into a composition of the whole. Daniélou views this centripetal motion as a work of immanence connected to the idea of wisdom – quite contrary to an institutionalised state religion cut off from Life, whose values are no longer capable of integrating a collective body in a world configuration without recourse to a dogmatic abstraction or an oppressive fanaticism. But the fact that Orphism turned away from the religion of Nature (that of Dionysus) through its spiritualist reform is less an ‘anthropological revolution’ (as Girard says of Christianity) than a distancing from the most important human question: the question of relations or, more precisely, the question of (re-)integration of man with the totality of Creation. For Daniélou, the rejection of rites, myths, and sacrifice (as instances of regeneration and distribution of energy in the order of manifestation)34 means entertaining the illusion that human beings, isolated from their sphere of relations (not only inter-human), can reshape and run the world in the best possible way. This detachment of the whole starts with the conception of Nature connected to savagery, to pure instinct, and to the image of a primitive barbarian who must be socialised to enter the human sphere and become the recipient of the ‘dignity principle’. In Hellenistic culture, such ‘barbarianism’ and such ‘primitivism’ are attributed to man prior to Orpheus35. Daniélou’s wager, clearly announced, but feebly articulated in his work owing to contextual limitations, is to reveal the background of this ‘otherness’ beyond the commonplaces of cultural homogenisation.

A note on the ‘archaic-satanic’ split

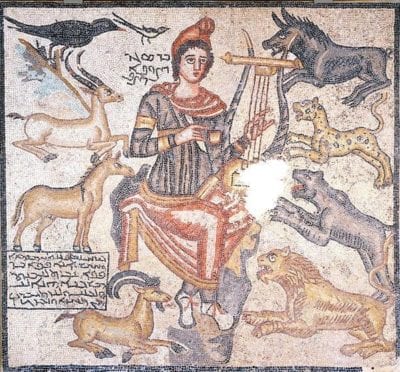

Roman Orpheus Taming Wild Animals. Roman marble mosaic. Eastern Roman Empire, near Edessa. Source: Dallas Museum of Art

Roman Orpheus Taming Wild Animals. Roman marble mosaic. Eastern Roman Empire, near Edessa. Source: Dallas Museum of ArtIn Achever Clausewitz, Girard declares, “We are now in a period when anthropology will be a more relevant tool than political science”36. I would say that this prophecy is fulfilled, but not in the way that Girard means. In his opinion, Christ’s message is an anthropological revolution that reveals what was hidden in all the ancient myths: the innocence of the sacrificial victim. The content of pagan myth and Christian truth is in the end the same, but their hermeneutic orientation is quite the opposite. The paradox I mentioned at the outset of this presentation arises from the observation that Christ revealed an anthropological truth that has no historical incarnation, since “we [humans] are incapable of accepting it”37. It can be said that, from Girard’s point of view, Christian knowledge is simultaneously knowledge of the archaic (which, as motor of the ‘sacred’, neutralises it) and of itself (since it comprises a message of profound transformation of human desire). The revealed truth of Christ, however, pierces its way through that knowledge, and the historical effects of the gap between the Christian event and the knowledge of it prove to be both tragic and parodic. Although the apologists satanized the archaic sacred (as we saw in the case of Clement of Alexandria), history shows that in reality the satanic is actually the immediate consequence of the elimination of the archaic sacred. This is why one may think differently from Calasso when he says that Girard is the last church father. Actually, Girard has shown – faithful, as he claims, to the truth of Christ – the snare of (ecclesiastical) knowledge that coincides with the truth (of Christ). It is unnecessary to quote pagan sources to clarify this point, since it is clearly expounded in a crucial scene in Mark’s Gospel (8, 31-32) in which Jesus announces his Passion. He says to his disciples that the Son of Man must greatly suffer (pollà patheîn), be rejected, killed, and three days later rise again (anastênai). Peter cannot comprehend this revelation. He takes Jesus aside and reprimands him. Jesus reacts in the same manner: he reprimands him saying, “Go away from me, Satan”. The verb used for both Peter’s and Jesus’s action is the same: epitimân (‘rebuke’, ‘reprimand’, ‘threaten’), a verb employed by Jesus when he casts out demons38. The clash in this passage is radical: Jesus “speaks his word freely” (parrêsíą tòn lógon elálei), whereas Peter, drawing him towards himself (proslabómenos), seeks to trap him in his narrow and pusillanimous point of view39. His inability to conceive of the Passion makes him the adversary of the Logos40.

What Girard’s Christianity reveals, contrary to what one may think, is the constituent difference between Christ’s message and its implementation in history. I would say that the Christian revelation is a singular anthropological event, and knowledge will never be able to make up for its effects with the moral certitude postulated by its apologists, since this knowledge is too narrow. It reveals nothing beyond its own effects. On the contrary, it conceals a whole dimension to which Daniélou, with his ‘return to paganism’, wished to return concisely, starting from his experience in India and his later conceptions concerning the religious amalgam he termed ‘Shiva-Dionysus’. He sought, I feel, a wider humanism, de-centred in relation to its own history of effects. In this sense, retracing the steps of mankind does not mean going back to the primitive, but revealing the complexity of human relations with otherness – not only in the sense of other humans, but also in the sense of ‘other than humans’, that is, plants, animals and gods. Such vision of the whole would make it possible to move on from observing the tragic to working on integration, from the radicalness of the beginning to the overall composition, from isolated singularity to articulated plurality, from a criterion of truth to a work of compossibility.

Calasso speaks of the superstition of modern society, and he’s partly right: modern man believes that ‘Nature’ no longer exists (as a place outside society), and for that reason he is invaded by a sacred that he has no tools to master. At the same time, Calasso takes a position that seems united with the idea of human progress (related to ‘high’ culture), a paradigm that reduces ‘Nature’ to a sphere of obscure and uncontrollable powers, to a “domain abandoned to the arbitrary”41, irremediably shielded from the law – as though it didn’t include societies – outside Western culture and all the parallels traced by homology with it – that can teach us the relativity of our convictions. The irruption of global configuration with rules and behaviour that are contrary to our most rooted convictions suffices to envisage the historical chiaroscuro that surrounds them. It is precisely the domain largely criticised by Calasso, the new anthropology42, which – in my opinion – provides a very clear sign of a possible opening towards the other – an opening that, with all its risks, should question the certainties of our heritage and unveil its blind spots. So much still has to be done, and it is not a matter of taking sides for a phantasmatic exteriority, but rather to take a step forward in the task of widening our horizon of experience with self-criticism and a good dose of anti-dogmatic spirit. By way of conclusion, I would like to quote Philippe Descola, whose following reflection summarizes my purpose: “anthropology shows us that what appeared eternal, the present time in which we are currently locked down, is quite simply one way, among thousands of others that have been described, of living our human condition”43.

- I share Gianni Vattimo’s view on the continuity between the Christian work of desacralization of Nature and the modern secularization process so characteristic of the West (cf. René Girard, Gianni Vattimo: Christianisme et modernité, Paris 2014, p. 33). This does not mean that the two phenomena are identical, but rather that the religious constraints linked to ancient cults and ritual practices eliminated by Christianity form the basis of the rational expulsion of the ‘archaic religious’ to which Girard refers (cf. Ibidem, p. 12). When Calasso subscribes to the Hölderlinian dichotomy between ‘Oriental ardour’ and ‘Western sobriety’ as well as to the need for aesthetic distance in relation to the gods and the introduction of a consciousness-gap (out of which is grounded the rational path of negation), it becomes clear that the archaic idea of the sacred is determined by the view that has subordinated it to the well-founded ratio (cf. Roberto Calasso : La littérature et les dieux, Paris 2001, pp. 49-51).

- In this respect, cf. Jean Daniélou: Message évangélique et culture hellénistique, Tournai 1961, p. 19. Justin’s example concerning the prejudices (pseudodoxíai) and ignorance (agnosíai) of pagans, also given by Jean Daniélou, illustrates this intention very clearly. It also reveals the double nature of Christian criticism: criticism of myths and criticism of pagan philosophy which deems itself discontinuous with regard to myth – but never manages to disentangle itself from the mythical matrix.

“It is only through the multiplicity of approaches that we can draw a sort of outline of what transcendent reality may be. The multiple manifested entities that underlie existing forms are within the reach of our understanding. Any conception we may have of something beyond will be a mental projection” (Alain Daniélou : The Myths and Gods of India, Rochester: Vermont 1991, p. 5). - The main consequence of anthropocentrism is the idea of an ‘objective nature’, that is, a nature separated from and indifferent to the activity of the human spirit. Against this dualism, Alain Daniélou proposes an interdependence principle of all beings: “All the elements which constitute the world are interdependent […]The mineral, vegetable, animal and human worlds, as well as the subtle world of spirits and gods exist through and for each other” (Alain Daniélou: Shiva and Dionysus, New York 1984, p. 11).

- This ‘experience of the other’, in the way Daniélou understands it, also implies a lengthy immersion in another culture to the point of reaching a true deconstruction of the interaction established between the inherited collective perspective (pole of identity) and reality itself (ethnocentric reduction).

- “All people are supposed to be equal but only according to the model of the average, pseudo-Christian European. No one thinks of being equal to the Pygmies, the Santals of India, or the Amazonian tribes” […]Most of the problems of today are a result of monotheistic ideologies taught by prophets who believe themselves to be inspired and claim to know the truth. This is obviously absurd, for there can be no single, absolute truth. The reality of the world is multiple and elusive” (Alain Daniélou: The Way to the Labyrinth, New York 1987, pp. 318 and 329).

- In this connection, cf. Philippe Descola: Constructing Natures. Symbolic Ecology and Social Practice, in: Philippe Descola and Gisli Parsson (ed.): Nature and Society. Anthropological Perspectives, London 1996.

- The consideration of the multi-ethnic and pluri-religious composition of India that Daniélou maintains distinguishes his approach from the Hinduism of the ‘Indo-European’ project, which determined any reflection on India during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

- The persecution of pagans and heretics in the Middle Ages, the slave trade (Christian and Muslim) in Africa, the conquest of America and the colonisation of Australia are clear examples of ‘mankind’ seeing in the other merely a deforming mirror of itself.

- For a critique of abstract dualism between Western objectivity (here: alienation) and native wisdom, cf. Bruno Latour: Politiques de la nature, Paris 2004, pp. 62-63.

- Georges Bataille: L’érotisme, in: OEuvres Complètes X, pp. 7-270, quotation p. 88.

- On the relationship between primitive peoples and supernatural realities, cf. Mircea Eliade: Aspects du mythe, Paris 1963, pp. 22-26. Cf. the relationship between total hermeneutics and the transition to the transhistorical, amongst others in La nostalgie des origines, Paris 1971, pp. 102-105.

- Cf. René Girard: Achever Clausewitz, Paris 2007, p. 20.

- Cf. Georges Bataille, L’érotisme, in: Oeuvres complètes X, pp. 118-120. We should recall that, for Bataille, animality, as a sphere of immanence on this side of any subject-object differentiation, is the inner limit to which the human condition experiences the ambiguous sentiment of the sacred (cf. Georges Bataille: Théorie de la Religion, in: Oeuvres complètes VII, pp. 281-361, quotation p. 302).

- Cf. Alain Daniélou: Shiva and Dionysus, p. 229.

- With the central motifs that accompany it: new message, power to heal, passion, death, descent to the underworld and resurrection.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou: Shiva and Dionysus, p. 229.

- One of the subtitles in Shiva and Dionysus, p. 229.

- Alain Daniélou: Shiva and Dionysus, pp. 230-231.

- Alain Daniélou: Shiva and Dionysos, p. 225. Translation from the French slightly modified.

- Daniélou refers to Megasthenes, who visited India around the beginning of the 3rd century BCE, to establish a parallel between the retinue of Dionysus and that of Shiva (cf. Shiva and Dionysus, p. 206). According to Megasthenes, there were contacts between Alexander and the Jain sages – whom he termed gymnosophists (cf. Jean W. Sedlar: India and the Greek World. A Study in the Transmission of Culture, Totowa 1980, pp. 68-69).

- There are more in Shiva and Dionysus, but the other elements can largely be subsumed by those mentioned in my list: the phallus is symbol of the power of creation and inexhaustible energy (cf. the satyrs and the extension of the ‘divine’ to the human and animal sphere); the bull is the zoomorphic form (with which the other animals mentioned by Daniélou are closely linked: leopard, lion, panther; the serpent is a subterranean form (land and water), which has links with the animal and vegetal worlds. When Daniélou speaks of sacred plants, he also refers to the sacrificial function of soma, which may be compared to the notion of pharmakós (in the sense of ‘remedy’ and ‘poison’), a term linked to theophagy (ingesting the deity). It is not by chance that the caduceus of Asclepios is entwined with a serpent.

- The affirmation of the vital power associated with the phallus in Daniélou reaches metaphysical dimensions, contrasting with the notion of desire, which reduces this force to its aspect of lack, limitation and finitude (cf. Alain Daniélou: The Phallus, Inner Traditions 1995, pp. 16-18).

- In this connection, cf. Erich Küster: Die Schlange in der griechischen Kunst und Religion, Giessen 1913, pp. 68, 138 and 149).

- Cf. Protrepticus, § II.13.1.

- Zeus’s incest with Persephone, which produces a son (Dionysus) in the form of a bull (cf. Protrepticus, § II.16.1).

- This aspect is unclear in Clement who wishes to make a radical contrast between Orpheus (the sophistés as a skilful artist and charlatan) and Christ (the truth of the incarnate lógos), but it becomes a strategy used by later apologists, such as Eusebius of Caesarea, whose Praises of Constantine and Speech for the Thirty Years of Reign no longer show a rejection, but rather an acceptation of the pagan heritage for apologetic purposes.

- Clement of Alexandria alludes to this sequence (cf. Protrepticus § 18.1., particularly the use of adverbs próteron… épeita).

- Thus a double ontological spread is assured: the smoke for the gods (distinction between divine and human) and the cooked meat for humans (distinction between human and animal). The lexical distinctions between pyrouména (things grilled), phôzómena (things roasted) and ômá (things raw), from Hippocrates to Plutarch, are central to the way in which the Greeks treated not only the distribution of beings, but the defining of culturally valid parameters concerning the problem of ‘same’ and ‘other’.

- Cf. Marcel Détienne: Dionysos mis à mort, Paris 1977, pp. 173-174.

- Calasso alludes to Aristophanes: The Frogs 1032 sq., where the precise phrase is apéxesthai phonôn which is cloasely connected to the apéxesthai brôtôn thnêseidíôn kreôn of Diogenes

- Laërtius VIII, 33 (apud Otto Kern: Orphicorum fragmenta, Berlin 1932, p. 62. Cf. also Erwin Rohde: “Nahrung von getödten Thieren”, Psyche. Seelenkult und Unsterblichkeitsglaube der Griechen, Band II, Tübingen 1921, p. 125, Fußnote 3).

- Apud Otto Kern: Orphicorum fragmenta, pp. 33-34.

- In this connection, cf. Clement of Alexandria: Protrepticus, I.1.1.

- “… no being can exist except by devouring other forms of life, whether vegetable or animal, and this is one of the fundamental aspects of created nature. Life in the world, both animal and human, is nothing but an interminable slaughter. To exist means to eat and to be eaten” (Alain Daniélou: Shiva and Dionysus, p. 164, cf. Bṛhadāraṇyaka-Upaniṣad 1.4.10. Etāvad vā idaṁ sarvam annaṁ caivānnādaśca [this whole universe is but food and eater]; yathā ha vai bahavaḥ paśavo manuṣyam bhuñjyuḥ, evam ekaikaḥ puruṣo devān bhunakti [just as numerous animals are at man’s service, just so each man is at the gods’ service]). These lines can only be understood in relation to their conception of Vedic sacrifice – including the most shocking and extravagant aspects of the puruṣamedha and the aśvamedha – on which I have attempted to cast light in my paper at the BNF, through the exercise of reversion by taking Daniélou’s interpretation of the myth of Satī’s dismemberment in the Kālikā Purāṇa. Cf. René Girard’s conference in Paris titled Le sacrifice dans l’Inde védique (available in audio-visual format), in which he interprets the sacrifice of the ‘macanthrope’ Puruṣa in Ṛgveda 90.10. (perhaps the phrase puruṣam vyadadhuḥ in Ṛgveda 90.10.11.?) as a dismemberment: www.youtube.com/watch?v=IIxRSKg9Rgc

- Horace, in his Ars Poetica (vv. 391-393) and Themistios in his Orationes (XXX 349 b) provide two clear examples presenting the clash between the domination of the horde of instincts in the man of the forest and the civilising role of Orpheus that puts an end to the hell of primitivism.

- René Girard: Achever Clausewitz, p. 27.

- René Girard: Achever Clausewitz, p. 17.

- Cf. Mark 1, 25 and 9, 25.

- Cf. the highly lucid observation of Benoît Chantre: “Each acts only for his own survival, and that is hell” (Les derniers jours de René Girard, Paris 2016, p. 78) which, in my opinion, makes his second definition pointless: “Hell is the kingdom of a violence whose mechanism we must understand” (Ibidem, p. 157).

- This adversary (Peter-Satan) matches the eschatological link of the Christian anthropos. In this connection, cf. Johann B. Metz: “’Satan’, said Jesus to Peter and ruthlessly marked the awkwardness and ineradicability of lurking misunderstanding” […]“People’s thoughts, not actually immodest, arrogant, contemptible thoughts, but quite simply the obvious thoughts of people” (Messianische Geschichte als Leidensgeschichte, in: Johann B. Metz, Jürgen Moltmann: Leidensgeschichte: Zwei Meditationen zu Markus 8, 31-38, Freiburg/Basel/Wien, 1974, pp. 37-58, quotation pp. 41-42).

- Roberto Calasso: La rovina di Kasch, Milano 1983, p. 189.

- I refer to the ‘ontological turning point in anthropology’, whose main works (Philippe Descola, Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, Bruno Latour, Tim Ingold, et al) provide an articulated answer to Calasso’s objections. Frédéric Keck, Ursula Regehr and Saskia Walentowitz summarise the novelty of this turning point in the following terms: “The ontological turning point is a new way of posing the problem that lies at the heart of modern anthropology. Can we take seriously such paradoxical statements as “The Bororos are Ararás […], ‘the jumeux are birds’ […]or ‘powder is power’ […]? An ontological approach to these statements refuses to attribute them to irrational beliefs, to linguistic metaphors, or to mental totalities, to pose the multiple realities of which they should be the expression” (Frédéric Keck, Ursula Regehr, Saskia Walentowitz: Anthropologie. Le tournant ontologique en action, in: Tsantsa 20/2015: L’anthropologie et le tournant ontologique – Anthropologie und die ontologische Wende, pp. 4-9, citation p. 4).

- Philippe Descola: Diversité des natures, diversité des cultures, Montrouge 2010, p. 38.