Adrián Navigante

PHALLIC REMNANTS A NOTE ON DIVINE EROS AND THE (NON-)PLACE OF MASCULINITY

Alain Daniélou’s The Phallus is a book that seems foredoomed to oblivion. It was written in the same period as his highest achievement, the complete translation of Vātsyāyana’s Kāmasūtra, and it was also contemporary to a paradigm shift in Western culture as a result of the great impact of gender studies and deconstruction theory, both of which implied a revision (and also a reversal) of phallocentrism and logocentrism as oppressive instances of male dominance. In this essay, Adrián Navigante attempts a new reading of this seemingly insignificant book (in the light of Kāmasūtra) containing an outdated world-vision (in the light of the new cultural paradigm), an interpretation that seeks to do justice to the singular aspects of Daniélou’s quest, among others the distinction between male archetypal power and patriarchal ideology, but above all his elaboration of a chthonic philosophy related to the figures of Shiva and Dionysos, mirrored in the last developments of Jungian psychology.

French edition of Alain Daniéloiu’s book The Phallus (Puiseaux 1993).

French edition of Alain Daniéloiu’s book The Phallus (Puiseaux 1993).The In-Significance of The Phallus

Alain Daniélou’s Le Phallus was published one year before his death, in 1993, as part of an editorial series called “Small Library of Symbols [petite bibliothèque des symbols]” by the French publishing house Pardès1. The purpose of that series was to select several cultural key-terms whose “symbolic pregnance”2 calls for special treatment (the tree, the Celtic cross, the heart, the bull, etc.) and publish a short study about each of them. Daniélou chose a subject dear to him, which he had been dealing with mainly within the Hindu context – focusing on Shiva theology and liturgy – i.e. the term liṅga. He broadened the scope of this term not only geographically (beyond India) but also historically (extending his reflection to rock engravings of the late Paleolithic and early Neolithic), thus compelling him to summarize a colossal amount of archeological, anthropological, sociological, and psychological material in a short essay. It was too ambitious an idea for such a meager book. Apart from that, his attention at that time was almost exclusively drawn to his translation of Vātsyāyana’s Kāmasūtra, the first version of which appeared in 1992. For most people, the highest achievement of Daniélou’s later phase was without any doubt his first complete translation of the Kāmasūtra. In the light of that achievement, Le Phallus appears as an insignificant byproduct.

The progressive changes that took place in the second part of the XX century concerning male power and female submission3 as well as the deconstruction of the logocentric mainstream in Western culture4 do not facilitate any restitution of value in a book that seems to celebrate problematic aspects of patriarchal ideology such as vigor, power and heroic courage5, combined with a good dose of homoerotic hedonism. To complicate things even more, the book contains misquotations and deviant translations rendering the argumentation obscure. Just three examples will suffice to make my point clear: one of Daniélou’s quotations about liṅga worship is falsely ascribed to the Puruṣa Hymn [puruṣasūkta] of the Ṛgveda6, whereas in fact the term liṅga does not occur at all; a passage of Claude Conté’s book Le réel et le sexuel (1992) dealing mainly with Lacanian psychoanalysis is confusedly related to Sigmund Freud7; and some quotations from the Śiva Purāṇa dealing with metaphysical and soteriological questions are reinterpreted in the framework of erotic ritual and divine pleasure8. So, in talking about Le Phallus, its problematic character and especially its insignificance – both within Daniélou’s written production and in the light of history – assert themselves as a kind of hermeneutical verdict.

There are, of course, weak and strong hermeneutical attempts. Weakness usually goes hand in hand with a tendency to take short-cuts and give easy answers, to consider oneself more intelligent than the author in question to the point of denying the possibility of a reverse-side, to block every transversal opening, every subversive or digressive split, every possible loop or turn. Strong attempts, on the contrary, are those that insist on disclosing unthought-of aspects even if there seems to be no ground for them. This essay is about the in-significance of Daniélou’s Le Phallus, which means the inner, inherent, or particular significance that the book’s main line of argument has for his own understanding of Shaivism and, by extension, for a possible and extended dialogue with Western sources. Some of those sources are (rightly or wrongly) quoted in the book, others must be inferred, most probably because Daniélou was unaware of their existence, but they are closely related to his problematic. The in-significance of Le Phallus is not only what remains from that book today, but mainly what re-defines a very particular position – that of Daniélou – with regard to the place of masculinity and the question of desire and pleasure beyond the organic substrate and the psychodynamic structure of human sexuality. At a time when phallic reference is mainly associated with patriarchy and the tyranny of logos, its in-significance would be a reversal of perspective capable of introducing another dimension of interpretation and understanding. This dimension is almost invisible in Daniélou’s Le Phallus, but not inexistent. His attempt points in that direction, so it is worth gathering the phallic remnants and assigning them a proper place in today’s context. It is a risky attempt, but it is worth taking that risk.

Archeological Contortions and Vacant Places

To begin with, I will leave aside false debates surrounding Daniélou’s apparent (mis-)use of the term liṅga to mean exclusively the male sexual organ. Daniélou was well aware that the Sanskrit term also denotes a mark or a sign (that of Shiva in the order of manifestation) and subsequently a cult object (the embodied and energy-laden presence of the god)9. Suffice it to name two relatively clear examples of this awareness in his book Shivaïsme et tradition primordiale: “the deity can be perceived only through its creation, its sign, its liṅga […] it is not the phallus itself that is venerated, but that of which the phallus is the sign. Why is the linga venerated? Because it is the symbol of something permanent, the archetypes that reveal the nature of the universal person”10 . Such statements are far from a naturalized view of Eros. However, the layer of meaning related to sexuality is present and must be considered in its entire scope, which is that of erotic transcendence. Shiva is for Daniélou the expression of desire in its most intensive form, desire without lack or in other words sensuous plenitude (which Daniélou relates to the Sanskrit term ānanda), hence his ithyphallic character (codified in the expression ūrdhva-meḍhra = erect penis). It is a symbol of the most powerful self-affirmation of Life: “It is only when the penis [upastha] stands up straight that it discharges the semen, source of Life. It is then called ‘phallus’ [liṅgam]”11. Self-affirming Life is life at large, life at its peak. It permeates human existence and can fulfill the destiny of an individual if a change of perception is achieved concerning one’s own vital forces as well as those of the environment. In our normal (i.e. impoverished or alienated) state, such intensity escapes perception and seems to be abstract or unachievable. Daniélou’s Le Phallus is an effort to pierce that veil and realize the concrete character of symbols as well as their living source. The particularity of Daniélou’s attempt consists in his operating not only with Indian references, but also with a combination of archeology and psychoanalysis. This procedure proves to be much more revealing and central than it seems at first sight, since his combination of archeology and psychoanalysis enables him to introduce a specific referent, masculinity, within a much broader question: that of the primordial source of Life.

Daniélou does not reduce the question of the phallus to the sexual organ but rather amplifies its scope beyond biology, psychology, and history, driven by his profound conviction that the other – and complementary – side of human sexuality is divine Eros.

Every question of origin implies a contortion, since human experience is shaped within limits – and limitations –, whereas reaching the origin is like disclosing the unlimited. A contortion consists therefore in forcing or twisting something out of shape to make room for something incommensurably other. The passage from the first to the second chapter in the first part of Le Phallus, that is from the historical perspective to the symbolic one, accounts for that contortion. At the beginning of the first chapter, we find a quotation from Alexander Marshack’s book The Roots of Civilization (1991); at the end of the second chapter, we find a reference to Claude Conté’s Le réel et le sexuel (1992). In a way, Daniélou contorts the meaning of both passages in order to arrive at the question of origin – in this case the origin of both biological life and spiritual pleasure – without falling back on worn-out formulations of the type found in Perennialist metaphysics or Neo-Vedantic doctrines. His contortion forces an opening through which he reconfigures – and subverts – the ‘validity’ of the Western sources he uses in the light of what he calls “Shaivite mysticism” and “Dionysian orgiasm”12. Alexander Marshack locates the phallus cult in the context of early modern humans, that is within homo sapiens’ representational art and notation. The symbol of the phallus is, in the context of his book, an earlier – but certainly not the earliest13 – form of reference or cultural model to express important processes structuring the life of male humans, after humanoid tool-making and Neanderthal rites and ceremonies. Within Lacanian psychoanalysis, referred to rather cryptically in Daniélou’s quotation of Claude Conté, the phallic phase is seen as a structuring function of human subjectivity, something that constitutes and shapes desire – as opposed to any biological or instinctual need. There is something primordial in the phallic phase. Its main constituent is not in space and time, but at the same time the phallus symbolizes the irreplaceable loss of the primordial object – the mother –, inaugurating the possibility of all vacant places for her multiple substitutes. In Le Phallus, Daniélou tries to go beyond both the historical limitation of archeology and the structural reduction of psychology by means of his Shaivite-Dionysian reconfiguration of the vacant place left by the phallus in Western culture. This movement of thinking constitutes the most interesting aspect of Daniélou’s book – a book otherwise condemned to be a forgotten by-product of his monumental Kāmasūtra.

Daniélou’s reconfiguration is worth analyzing in some detail. Partly because it implies a significant distinction between archetypal masculinity and the patriarchal social order so vehemently criticized in post-modern culture, but also because it opens another kind of interrogation concerning the status of desire and pleasure in human experience. In The Roots of Civilization, Aleksander Marshack does not lend much importance to the vocabulary of sexual impregnation related to the phallus. This may seem contrary to what Daniélou does, but in fact the aspect disclosed by such a shift in attention turns out to be decisive for Daniélou’s treatment of the phallus as archetypal symbol. Marshack defines the phallus as a symbol of the masculine process that is at the origins of ancient rituals and myths14. Phallus is in this sense process and relation susceptible of being integrated into a narrative scheme – foundational stories that set the parameters of human culture in a very general sense, but at the same time reveal something special about masculinity: “None of these stories concerning masculine processes […] need involve the female”15. Even if Daniélou seems to accept the XIX conviction – stemming from Johann Jackob Bachofen’s Das Mutterrecht (1861) – that the cult of the Mother is primordial and the phallus may have been introduced after the rise of patriarchy (that is, in the Neolithic)16, he pleads nonetheless for the recognition of a masculine dimension transcending historical determinants as well as biological markers17. His support in this sense is the mythology of Shiva: As creator of the world, Shiva is the giver of seed [bīja], and he is also giver of pleasure [bhogadātṛ]18. The seed is not only the primal spurt of life in its manifested form but also the creative power of the god19. This creative power is not primarily ‘cosmic’, as Daniélou says, but rather chthonic. It comes from the depths, not from the heavens. It is a stream of Life unbound, not a mere pneumatic image, and it should therefore not surprise us that Daniélou considers the highest pleasure [jouissance] a “sensation of the divine”20, rejecting thus the usual split between the finitude of human existence and the plenitude of divine ecstasy. But that plenitude is prior to logos, prior to patriarchy, prior to any form of rationality defining the parameters of any male-dominated society.

If Daniélou recurs to mythology, it means that the axis of chronology is not sufficient to account for the phallus. Still more: mythology is verticalization, translation into narrative devoid of objectivity and imagery unaffected by epistemic formalization. It is the access to the symbolic dimension of relations, inasmuch as symbols are experienced (not merely learned and deciphered) as real processes – or as embodiment. When Daniélou says that man is “the phallus-bearer [liṅga-dhāra], the servant of his sex”21, he does not reduce the question of the phallus to the sexual organ but rather amplifies its scope beyond biology, psychology, and history, driven by his profound conviction that the other – and complementary – side of human sexuality is divine Eros.

Faces (and veils) of Eros: anatomy, formal structure, symbol

The path toward divine Eros is not straight but – as Daniélou said elsewhere of knowledge – twisted22. In the case of Le Phallus, it contains a psychoanalytical detour that should not be overlooked. As opposed to authors like René Guénon and Julius Evola, Daniélou does not reject psychoanalysis from an external point of view23 but rather operates with transversal distortion leading to a reversal of its categories. In this sense, his reference to Freud through the means of Claude Conté’s book Le réel et le sexuel is – I daresay – symptomatic: “sexual reproduction makes the individual a contingent bearer or appendage of the genetic code. The discovery of the phallic phase means the recognition of the supremacy of the symbolic order in relation to the real and the imaginary… the anteriority of the signifier with regard to the signified”24. As I pointed before, Daniélou makes an indirect quotation of Freud out of this passage, when in fact it is about the Lacanian version of the phallic phase. This aspect shows us how little Daniélou knew of psychoanalytic theory, but at the same time how sharp his intuition was as to the central aspect of the problem, which I intend to summarize in what follows.

In Freud’s Drei Abhandlungen zur Sexualtheorie (1905), the role and function of the phallus in the context of infantile sexuality is amalgamated with anatomical and genital aspects as well as phantasmatic projections about sexual difference, the starting point of which is the concrete situation of a male infant. Freud says that the existence of the penis is presupposed (by the infant) in all people: “the infant vehemently insists on this conviction in spite of the contradictions he very quickly observes [in seeing female infants]”25. The passage from denial to acceptance of that difference he calls the ‘castration complex’, the acceptance of the absence of the penis being gained through the conviction that, in the case of a female child, there was once a penis – but it was severed at some point. The difference between ‘penis’ and ‘phallus’ becomes clear: the penis is a specific organ; the phallus a universal premise. However, in Freudian theory, the penis plays a central role in the identification of both sexes. For Jacques Lacan this emphasis on the organ reveals that the premise (phallus) lacks a more consistent formulation and risks being reduced to the organ (penis). Part of his ‘return to Freud’ therefore consists in formalizing – for the sake of universal validity – some aspects of the castration complex that in Freud appear too close to biology and anatomy26.

Lacan’s essay about the signification of the phallus, written in 1958 as a lecture for the Max Planck Society in Munich27, intends to correct such asymmetry. His verdict is the following: “The phallus in the Freudian doctrine is not a phantasm, if by phantasm we understand an imaginary effect. It is not an object, either, whether partial, internal, good, bad, etc. […], nor is it a symbolized organ like penis or clitoris […] The phallus is a signifier […] whose function in the intrasubjective economy of the analysis drops off the veil of the function it had in the ancient mysteries”28. This paragraph anticipates, apart from his reformulation of the castration complex, Lacan’s theory of desire and his notion of subjectivity. The phallus as universal premise must be irreducible to the sexual difference. As a result of this, it must be cut off from anatomy and biology and turned into a kind of primordial law structuring human desire. The term ‘signifier’, taken from Ferdinand de Saussure’s linguistic theory, meets the purpose. The phallic phase is the first instance of genital maturity, long before the biological attributes (so-called external genitalia) become operative in the life of the individual. This instance is therefore under imaginary dominance and constitutes the separation of drive-related desire from instinctual needs. In the space where human subjectivity is inscribed as being discontinuous with nature, Lacan situates the emergence of meaning – or symbolic content – for the libidinal economy of the individual.

Alain Daniélou at Zagarolo, Italy, in 1987, photo by Sophie Bassouls.

Alain Daniélou at Zagarolo, Italy, in 1987, photo by Sophie Bassouls.Within the context of Lacan’s reformulation, phallus means the interruption of the coupling ‘mother-child’ in which the body of the mother (the hole of the Real) reappears under phantasmatic mediation (the flux of the Imaginary) and the resulting veil tends to draw a net of references or a plurality of meanings in the world (the Symbolic order). The Lacanian phallus transcends anatomic, biological, and instinctual particularities; however, it is drastically distinguished from the transcendent – or transpersonal – status of symbols found in C. G. Jung’s Analytical Psychology. In his homage to Ernest Jones, Lacan points to the pitfalls of the Jungian figurations of the libido, in which the soul, “blind and lucid, reads her own nature in the archetypes that the world reveals to her”29. If the phallus is given a transcendent status as symbol, it ceases to be a signifier and becomes a signified, and as such it cannot assume its structuring function. An ultimate (mystical or magical) signification is re-introduced beyond the structural distribution enabled by the phallus as primordial signifier.

In this sense, signifier means “generic idea” and has nothing primordial in the ‘sacred’ sense of the term. Generic ideas30 must be empty of meaning in order to provide a plurality and distribution of meanings for the subject, but the subject must accept the consequences of phallic mediation. In Lacan’s theory, each relation of the object (of desire) entails an imaginary or intra-subjective tension which makes satisfaction impossible and throws the subject into a chain of permanent (and fragmentary) compensations for something forever lost – the Mother as object of desire. The phallus regulates this complex dynamic in taking the vacant place of the (already and forever) lost object, i.e. the Mother at the root of the Real, but this place is everywhere and nowhere. One could say that the phallus is like the unreachable center in the Labyrinth of human desire31. When Claude Conté writes “The discovery of the phallic phase means the recognition of the supremacy of the symbolic order in relation to the real and the imaginary”, he presupposes a recognition of the phallic instance as a law structuring the desire of the subject, that is its accessible reality, at a ‘healthy’ distance from any phantasmatic retrieval (in the sense of imaginary compensation) of an absolute object (or subtracted punctum saliens of the Real).

In the ancient religion of Shiva, which Daniélou retraces to the civilization of the Indus Valley, the ithyphallic character of the deity, called ‘Lord of Animals’ [Paśupati], reveals not only a religion of Nature, but also the immediate reverse-side of what we conceive as ‘nature’.

In Le Phallus, Daniélou semantically inverts the key terms of Claude Conté’s sentence. In Daniélou’s appropriation, the real is not the unrepresentable beyond all systems of reference, but reality as articulated in the social life of individuals. The imaginary is not the narcissistic stage of human fantasies, but the capacity to anthropomorphically represent a power that ultimately transgresses social order and human interaction, a power that can only be retrieved (at least partially) if one realizes a symbol on the level of embodiment, ritual performance or change in perception. In other words, the supremacy of the symbolic is for Daniélou the possibility of establishing a link with the transgressive agent of power that renders desire an instance of plenitude and a door to the experience of something more-than-human. In the ancient religion of Shiva, which Daniélou retraces to the civilization of the Indus Valley, the ithyphallic character of the deity, called ‘Lord of Animals [Paśupati], reveals not only a religion of Nature, but also the immediate reverse-side of what we conceive as ‘nature’. The erect phallus may as well be taken as a symbol of the power of fertility, but that is not the key to its more-than-human character: “Erotic ecstasy is only secondarily a means of reproduction […]. The union of Shiva and his lovers […] is not procreative”32. Daniélou affirms a transcendent character in Nature which nevertheless cannot be defined as strictly metaphysical, since its concrete power is no spiritualized principle detached from the natural setting, but something susceptible of being grasped on every level – especially that of human sensation. In this respect Daniélou quotes the following line of a very significant text for the construction of his Shaivite-Dionysian philosophy, the Liṅga Purāṇa: “The fundamental nature is called phallus. The one bearing this distinctive sign is the Supreme Being”33. This sentence does not affirm that the god, in this case Shiva as Parameśvara, is furnished with a male organ as specific gender-distinction. Phallus, as we have already seen, implies an excess of vital force in a vertical logic joining the subtlest element of manifestation with the most concrete instance of physicality34. The god’s phallus is the presence of what surpasses all forms in the world of forms, or more precisely: the totality of creation as erotic texture. Daniélou’s reference to the god Pan in the second part of Le Phallus is in this sense very instructive: “Pan means ‘all’. He incarnates the totality of the genetic energy, the whole of the gods and the whole of Life”35. For Daniélou, the underlying force of creation is Eros, and this force dominates the world before individuals are distributed in situations where finitude, frustration and unfulfilled desire gain the upper hand. It is from the background of that life-affirming conception that one should understand Daniélou’s definition of man as liṅga-dhāra [bearer of phallus]. The image is not that of a man with a male genital organ, but that of an open door in the realm of sexuality leading to what no human being can assume (the effects of a trans-personal force in his body) unless he discovers and realizes the correspondence of the erotic texture of creation and its inscription in individual existence36.

Masculinity re-placed: a Jungian appendix

There are two symptomatic instances in Daniélou’s Le Phallus. The first one – already mentioned and partially treated – is the displaced presence of Sigmund Freud; the second one – still to be deal with in what follows – is an emplaced absence of C. G. Jung. There is no single mention of Jung in Daniélou’s book, but there is an indirect reference that transforms that absence into a hidden presence. Daniélou uses the term ‘archetype’ related to the notion of phallus37. The numerous quotations from Mircea Eliade’s books that we find in Le Phallus lead the reader to the conviction that he took the term ‘archetype’ from Eliade38. Despite the latter’s efforts to delimit his notion of archetype from that of Jung39, it is difficult to accept that Eliade’s concept is – as he affirms – qualitatively different from the Jungian concept. He knew Jung’s Eranos lectures of the 1930s – where the notion of archetype is formulated for the first time –, and it didn’t escape him that, in Jungian psychology, the collective psyche is not merely psychological but transgresses40 by far the domain of mental processes41. Apart from that aspect, Daniélou relates the perfection of the soul with liṅga worship42. This means much more than a mere reference to śivaliṅga-pūjā; it implies a consideration on human behavior and its transformation by means of re-gaining the soul – which is a central motive in Jung’s early writings43. Daniélou’s remark about ritualized sexual union in Hindu tantra [maithuna] adds a qualitative element in this respect: “The form of the organs carrying out this ritual is the most important of symbols”44. The sexual organ becomes, in a proper ritual context and with the full awareness of the divine dimension disclosing itself, the physical condensation of an archetypal register of energy. It implies at the same time a transformation of the soul. The awareness is not to be focused on the sexual intercourse of two different beings but on the meaningful fluidity invading the body-soul complex to transform its existential parameters. The archetypal (or transpersonal) dimension is not regarded as independent from the sphere of finite beings and actions – despite Daniélou’s giving this impression in some passages of his book. It is an opening to a mode of relation that exceeds the worldly sphere of separated individuals, narcissistic veils and phantasmatic totalities. The significance of the phallus must be measured within the framework of an archetypal transgression instead of through the fixation of the transpersonal in an eternal realm detached from every concrete situation.

What is the meaning of this transgression? I have already shown that, in the context of psychoanalysis, the phallic function implies the exclusion of mystical fusion in the sexual act45. The only instance of unity is individual separation, that is, the consistency guaranteed by the phallic function – which is essentially linked with the linguistic notion of discrete units. Magical and mystical instances of ‘the One’ are for Lacan nothing but phantasmatic attempts to regain something lost from the very beginning. In this sense, any imaginary transgression of the symbolic order is regressive and therefore pathological – as Lacan said, the speaking-being [parlêtre] splutters in the Real. For C. G. Jung, archetypes are autonomous factors of the psyche and at the same time living entities of a non-objectifiable dimension of Nature – entities embedded in the instinctual structure of (human and non-human) beings. In the case of humans, consciousness plays a relational function in the face of that otherwise uncontrollable source of power. It can build a bridge and partially assimilate what comes from ‘the other side’. The transgressive character of archetypal energy (usually vehiculated in images) consists in dismantling the ego complex as main orientation factor through the intensity of its emotional effect. This effect blurs the discrete limits of individuality both in the subject and in the outer world, revealing thus a kind of experiential junction. In Symbole der Wandlung, the first version of which marked his irreconcilable break with Freud, C. G. Jung defines the phallus as a symbolic instrument of the libido46. In this case, the term ‘instrument’ does not mean something mechanical, and its subordination to the libido is not strictly sexual, either. The expression ‘instrument of the libido’ refers to a subjective formation or a self-regulating manifestation of a quantity of Life-energy. Libido is for Jung Life-energy in a transpersonal sense. It must not be reduced to psychosexuality (as in Freud) but redefines the sexual energy as part of a broader – not only collective but also cosmic – process. As such, it has a numinous and transformative character: it precedes and determines ego-consciousness before the latter can do anything to reverse the process and normalize the effects according to the best adaptation strategy to the immediate socio-cultural environment.

There is much more than a definition of phallus in C. G. Jung. In his autobiography Erinnerungen, Träume, Gedanken (1961), Jung relates a childhood dream that played an essential role in the type of relationship he established with the sacred and religion throughout his life. The dream was triggered by a prayer Jung’s mother recited to give him comfort when he went to bed, in which Jesus takes the children to him at night lest Satan should devour them. Jung’s association was that Jesus, regardless of his status as savior, was a devourer like Satan. In his dream, Jung discovers a dark, stone-lined hole in the ground near a vicarage, and he descends a stairway until he sees a chamber in which there is a throne with something standing on it: “it was a huge thing, reaching almost to the ceiling […]. It was made of skin and living flesh, with a rounded head on top with no face and no hair, and on the very top was a single eye, gazing motionless upward”47. In the dream, Jung remains paralyzed with terror and hears his mother’s voice: “Yes, just look at him, that is the man-eater”48. Jesus appears as a dark, chthonic presence, “a subterranean god” in the form of a “ritual phallus”49. The image breaks with the dogmatic conception of Jesus Christ as a heavenly figure full of love and kindness, son and father at the same time, the transfigured law of God that realizes the summum bonum. By contrast, the only hint of light in Jung’s childhood-dream – which stands for the bridge to ‘the surface world’ – is the eye at the top of the phallus. All the rest, the massive, fleshly and underworldly glans is the concrete and living revelation of the mystery of the earth in a numinous masculine image. Jung’s conclusion can be summarized thus: “Through this childhood dream I was initiated into the secrets of the earth. […] Today I know that it happened in order to bring the greatest possible amount of light into the darkness. It was a kind of initiation into the realm of darkness”50.

If one reads Jung’s account of his childhood dream with attention, the parallels with some of Daniélou’s descriptions in Le Phallus are significant. The chamber to which he descends recalls the garbhagṛha or ‘womb-chamber’ of the Hindus, where the ritual liṅga is placed, as well as the Dionysian chapels in ancient Greece containing metal or stone phalli. Both constructions are mentioned in Daniélou’s book51. The setting of Jung’s dream is a meadow close to a castle, a rural place detached from city life. Speaking of the installation of the ritual phallus, Daniélou says that the ceremony takes place “in secluded places or in the mountains […]. The ancient sanctuaries of Shiva, like those of Dionysus, were usually located away from cities”52. For Jung the subterranean god is “not to be named”53; he associated the dream-image with Jesus for many years when somebody else spoke of the latter, without being able to pronounce the name. In speaking of the phallic significance of certain objects, Daniélou points to the principle behind the allegoric bond, “according to which the pronunciation of the name of the god is forbidden”54. Indirect representation and interdiction of the proper name are aspects which, in relation to the numinous aspect of the phallus, should be taken and understood in a very concrete sense. One could say that such interdictions point to the fact that the energy always exceeds the form trying to encapsulate it. In other words, human limits (or human contours) are not only incapable of holding that energy but are also endangered – or traumatically affected – in receiving it. Instead of insisting on metaphysical theories about the transpersonal component of the phallus, I think it important to consider the experience of numinosity related to the sexual aspect and the passage from a physical or bodily sensation to another form of (embodied) consciousness, since that aspect shows quite another register of experience than the one established by the psychoanalytic theory in relation to human desire.

A very telling account – which explicitly includes references to Daniélou – is that of the Jungian analyst Eugene Monick in his book Phallos: Sacred Image of the Masculine (1987). Monick’s account is important because it brings the Jungian reflection on the phallus to a point that was not developed in Jung’s work (probably because of Jung’s lack of conviction about such a thesis). Phallos stands for an archetypal god-image correlating sexuality and numinosity, the chthonic character of which is not derived from the Great Mother but proves to be independently masculine. In this sense, Monick opposes not only Freud but also Jung: “Psychanalytic theory, whether Freudian or Jungian, gives singular primacy to the mother as the basis of life. This is an error. The lack of phallic participation in theories of origin forces phallos into distorting compensations to make itself felt and realized within therapy”55. It is because of this specific combination of archetypal numinosity and masculinity that the spelling of the word is modified to fit that of ancient Greek: Monick writes phallos instead of phallus – the latter being a Latinized spelling used by psychotherapists and historians of religion. The most important part of his essay is the personal account of an incident which may be termed ‘his encounter with phallos’. Only based on that account can he elaborate his own theoretical reflections on the relationship between archetypal phallic numinosity and the roots of male psychology: “As a child of about seven, in the early days of the psychosexual period which Freud called latency, I crawled into my parent’s bed one summer morning. […] Mother had left the bed to prepare breakfast. Father lay there asleep, naked. I went under the covers to explore. I may have had a flashing light with me, which would indicate an intention to investigate. […] I crouched in the darkness next to my father’s body, I came upon his genitalia. I focused the light and gazed upon a mystery. […]. What I do remember is the powerful effect the incident had upon me. I think now that I looked upon my father’s maleness as a revelation”56.

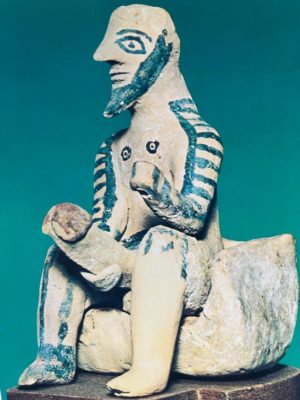

Greece Clay satyr. National Archeological Museum of Athens (in: Alain Daniélou, The Phallus: Sacred Symbol of Man’s Creative Power, Rochester: Vermont 1995, p. 97).

Greece Clay satyr. National Archeological Museum of Athens (in: Alain Daniélou, The Phallus: Sacred Symbol of Man’s Creative Power, Rochester: Vermont 1995, p. 97).Monick’s encounter is not with his father’s erect penis, but with ‘phallos’ (the word is written without definite article to emphasize the personification). The evidence of the numinous character of the encounter is the impression that image made on the seven-year-old child and the consequences of that episode in his later life. Contrary to what many readers may think, Monick’s book is neither about homosexuality nor about incest57. It is about the link between overwhelming experience (where traumatic impressions are not to be ruled out) and transpersonal meaning (which adds a spiritual dimension to psychology). His childhood episode triggered a life-long reflection on psychohistory and the Jungian conception of the archetype. In the XIX century, the beginnings of psychohistory were identified with the maternal domain. As J. Bachofen writes in Das Mutterrecht, the primacy of the feminine is a truth of nature [Naturwahrheit]: birth belongs to the mother, as well as the primal life-stuff related to the sphere of becoming. In the light of that chthonic femininity, masculine mediation (however creative it may be) implies a process of spiritual untying or detachment [Losmachung] from the powers of Nature58. Despite his broad reflection on ancient cultures and the undeniable value he ascribed to natural powers, C. G. Jung followed Bachofen’s line of argument, as a result of which, in the context of Analytical Psychology, the masculine element in the psyche ended up being identified with consciousness, reason and discernment rather than with the telluric powers of origins. In separating solar masculinity (related to logos and the heavens) from chthonic masculinity (connected with instinct and the earth) and making the latter independent from the domain of the Magna Mater59, Monick postulates a primal ground for archetypal masculinity in the psyche: “Phallos is more than the constant companion of the Mother, her plaything in Bachofen’s terms”60. In this way, he fully detaches male archetypal power from every aspect related to patriarchy, not only from the point of view of contents, but also because patriarchy is a historical fact out of which social complexes are organized, whereas archetypal masculinity belongs to the sphere of primal experience, mainly codified in ritual and myth.

Monick’s own encounter with phallos is a necessary support for his further reflections, but it is not sufficient to prove the transcendent significance of phallos. He therefore seeks in non-Western cultures confirmation of his own intuitions and speculations, and it is at this point that he resorts to Daniélou. Monick’s book was written in 1987, six years before the publication of Daniélou’s Le Phallus, but he found convincing elements to support his thesis in Shiva and Dionysus (1979): “Collective, explicit phallic worship is virtually nonexistent among Western people. It is not a present reality anywhere in the world save among certain Hindu believers in India, where Shiva as lingam (phallos) is outwardly acknowledged as an image of divinity. Shivaism, today a cult within modern Hinduism, is, according to Alain Daniélou, the oldest religion, having originated during the Neolithic age (10,000-8,000 B.C.) among the Dravidian peoples of what is now India, and carried by them to the Mediterranean. There it became the basis of Greek Dionysianism”61. It is not surprising that a similar formulation can be found in Le Phallus, for example: “India is the only region where the cult of the lingam, or the phallus, as well as its rituals and legendary narratives have been transmitted without interruption”62. Incidentally, Daniélou mentions similar manifestations to those of the Hindu context not only in ancient Europe but also in present-day Africa63. From Monick’s perspective, Daniélou proves with external sources something that needs to be added in Analytical Psychology if one intends to do justice to an essential dimension of numinosity. Of course one should remember Daniélou’s reference to the myth of Skanda, the Hindu god of war, “who was born from the sperm of Shiva when the latter fell into the mouth of the sacrificial fire and then into the waters of the Ganges”64. This emphasis on masculine reproduction without the intervention of the feminine element would be, in Jungian terms, a sign of the attention Hindu religion grants to the masculine archetypal dimension at root-level, that is, before the constitution of individual consciousness, rationality and symbolic structure as conceived by modern linguistics and Lacanian psychoanalysis.

Masculinity Re-Placed

Daniélou’s Le Phallus contains references to metaphysics and cosmology, sexuality and reproduction, liturgy and human desire, pleasure and spiritual realization. The device is very complex, and the guiding thread is not easy to follow since these levels appear intertwined with each other and some formulations sound contradictory. The phallus is fundamental nature, that is, it belongs to the chthonic realm, but at the same time it is related to the sun (as the progenitor of the earthly world). It is the manifest root of reality, but it has its roots in non-manifested reality65. It is at the same time a distinctive mark in the male body and a cultic object in the temple. It refers to a force permeating the totality of the manifested world, but at the same time it encompasses the world as a whole, inasmuch as the latter is – in its totality – the distinctive sign of Shiva’s power. This problem was referred to by Mircea Eliade in his book Méphystophélès et l’androgyne (1962): “An essential characteristic of religious symbolism is its multivalence, that is, its capacity to express many meanings at the same time, the connection of which is not evident on the level of immediate experience”66.

As I said at the beginning of this essay, Daniélou’s book is too short and too quickly written, one may say, to account for its own intent. It is rather insignificant if compared to his Kāmasūtra, and – already because of its own substance – it seems very difficult to detach it from the ideological shadow of phallocentrism and male dominance that is so criticized by contemporary feminism. However, there is another possible approach to the ‘insignificance’ of the book, which consists in changing the parameter of the comparison. The task would be to focus on the in-significance, that is, the inner significance of the content – the main aspect, the guiding thread, the punctum saliens to be distilled – which in many ways goes beyond ideological fixations. I daresay that Daniélou’s Le Phallus has an archetypal in-significance, and it is precisely that aspect that renders it not only readable but also interesting – even today. If Daniélou uses the term archetype, as I pointed out earlier, it is because there is the possibility of a structural synthesis in this term with regard to all the referents mentioned in the book. Or more precisely: the proliferation of symbols related to the phallus can be ordered around the question of “transcendent virility as the immanent cause of creation”67. One needs to be careful about not transforming that question into a dogmatic affirmation. Daniélou opens a horizon in which the remnants of a phallocentric ideology become pieces of a much deeper and more complex puzzle in which the phallus can be re-placed (or better situated) to fulfill other purposes.

I have used Jungian psychology as a missing link to account for that question in a consistent way. Paradoxically enough, the Jungian amplification must work through the Freudian territory of sexuality to properly introduce and do justice to the Shaivite-Dionysian reformulation. For Daniélou, sexual intercourse is not only a mechanism to release tensions or the frustrated search for a totality forever lost, but an act of creation re-enacting the coming to being of the world on the microcosmic level of one’s own body and soul. The bridge from individual act to cosmic significance is the phallus. Its power can only be dealt with ritually and liturgically, for the capacity of human beings in their constitutive limitations is not enough to assimilate it. The corollary is something very different from unbridled sexual activity. I would call it an erotic discipline involving sensation, perception, and attention in order to render the power of masculinity susceptible of surpassing the role to which it has been reduced in the course of so-called ‘human evolution’: patriarchy, rational power and alienation from (the sacred dimension of) Nature. The chthonic character of the phallus may seem too dark, irrational, uncontrollable or demonic, and together with possible representation of male dominance, it is susceptible of becoming a notorious symbol in the collective consciousness of many cultures. However, if we really understand Daniélou’s message, it is a power that needs to be acknowledged in its whole dimension in order to avoid such deviated and distorted compensations: “For the man filled with a love of Nature and driven by the quest of the divine, who succeeds in liberating himself from the taboos, superstitions, prohibitions and myths of modern religion, the phallus – image of the creative principle – will re-appear as luminous and unaltered principle, source of joy and prosperity”68.

- Alain Daniélou, Le Phallus, Puiseaux 1993. The book was translated into English (1996), Japanese (1996) and German (1998). All the quotations in this essay stem from the French original version.

- I take this term in the sense given to it by Ernst Cassirer, which emphasizes the passage from sensible lived-experience to a non-intuitive “meaning” that is not detached from its sensible basis but constitutes the very perceptive articulation of it. Cf. Ernst Cassirer, Philosophie der symbolischen Formen, Band III, p. 235.

- The shining example of that change is embodied in Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble: Feminism and Subversion of Identity (1990), which was defined as the most influential theoretical text of the 1990s.

- See for example Jacques Derrida’s critique of logocentrism, among others in De la Grammatologie, Paris 1972, pp. 20-23 (his “subversion of logocentrism” and his distance with regard to “the Father Logos”).

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Le Phallus, p. 15.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Ibidem, p. 24.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Ibidem, pp. 36-37.

- One clear example is the following passage from Śiva Purāṇa I.16.108: ciḥnakāryaṃ tu janmādi janmādyaṃ vinivartate [“the sign is the act of birth, but it also reverses birth”]. The sentence refers to the transition from non-manifestation to manifestation and to the minimal degree of appearance or limit-point, ciḥna (sign), which in the context has the same semantic value as liṅga. Daniélou translates: “The function [of an erotic ritual] is to give birth, but giving birth is excluded”, displacing the focus from the problem of manifestation to the question of pleasure beyond biological reproduction.

- In this respect, see Richard Davis, The Origin of Liṅga Worship, in: Donald Lopez Jr. (ed.), Religions of Asia in Practice: An Anthology, Princeton and Oxford 2022, pp. 150-161, especially p. 152.

- Alain Daniélou. Shivaïsme et tradition primordiale, Paris 2003, pp. 69 and 78, respectively.

- Alain Daniélou, Le Phallus, p. 11.

- Alain Daniélou, Le Phallus, p. 28.

- “This book […] did not involve an attempt to find the origins of the ‘first’ of anything, It was an analytical attempt to describe the way in which early modern humans, in one time and space, saw, abstracted, symbolized and imagined their world in time and space” (Alexander Marshack, The Roots of Civilization, New York 1991, p. 8).

- Cf. Aleksander Marshack, The Roots of Civilization, p. 320.

- Cf. Aleksander Marshack, Ibidem, p. 330.

- For example, in the following remark: “In his latest book Au nom du père, Jacques Dupuis has suggested that the passage from the worship of the vulva to that of the phallus could be linked to the discovery of paternity – something that is not evident in primitive civilizations” (Alain Daniélou, Le Phallus, p. 16).

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Le Phallus, p. 16. His quotations from Marshack are not quite precise, sometimes gathering bits from different paragraphs, but this has a specific purpose, since it is functional to his own divinization of Eros and his valorization of a masculine particularity inherited (not founded) by (male-)gendered beings.

- Cf. Śiva Purāṇa I.16.103: bhagavānbhogadātā hi nānyo bhogapradākayaḥ [Bhagavān is the one bringing pleasure into being; there is no other who can bestow pleasure].

- “Originally it was the golden seed of Brahmā (Prajāpati), who is called Hiraṇyagarbha (‘The Golden Womb’) in the Ṛgveda to denote his creative powers. The cosmogonic myth then postulated a golden egg instead of a golden womb, and this symbol was replaced in turn by the image of the god of the golden seed, an epithet of Agni and of Śiva” (Wendy Doniger O’Flaherty, Śiva: The Erotic Ascetic, London: New York 1981 [first edition 1973], p. 107.

- Alain Daniélou, Le Phallus, p. 29.

- Alain Daniélou, Le Phallus, p. 36.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Shiva et Dionysos, p. 155 : “The path of knowledge is twisted [vakra]”.

- René Guénon’s critique of psychoanalysis in Le règne de la quantité et les signes des temps (Paris 2005, first edition 1945) is no ‘critique’ but rather a demonization of the discipline, based on a shallow criterion – to say the least. Apart from expressions like “deviant nomadism” (p. 222 note 1, applied to Jewish authors who lost their religion: Einstein, Bergson and Freud), “malefic influences” (p. 223, related to the ‘lower astral plane’ psychoanalysis deals with) and “Satanic character” (p. 224, due to Freud’s materialistic bent), the main point in Guénon’s attack lies in the identification of the unconscious with a ‘lower realm’ – as opposed to the ‘higher’ realm of spiritual realization. This rigid division does not bear in mind the paradoxical character of unconscious processes, that is, not only the fact that regression opens the way to primordial processes – whose energy proves to be necessary for the cure, but also the consideration of the unconscious as the inscription of something that is not subject to time and space (and therefore impossible to place in a simplistic cartography of the high and low) within the very existence of an individual and its field of (real, imaginary and symbolic) relations. In his essay Superamenti della psicanalisi (1934), Julius Evola acknowledges a positive aspect of psychoanalysis, that of “having dissipated the rationalist myths of shallow psychology” (Julius Evola, Superamenti: critiche al mondo moderno: 1921-1933, p. 101), but soon he falls back on a Manichean opposition between the irrational, instinctive and atavistic on the one hand and the (supra-)rational, virile and heroic on the other. This one-sided rejection proves to be even more problematic if one bears in mind that Jung’s Depth Psychology is also included within the Perennialists’ demonology of the psyche.

- Claude Conté, Le réel et le sexuel : de Freud à Lacan, Paris 1992, quoted by Alain Daniélou, Le Phallus, pp. 36-37.

- Sigmund Freud, Drei Abhandlungen zur Sexualtheorie, in: Gesammelte Werke V: Werke aus den Jahren 1904-1905, Frankfurt 1999, pp. 95-96.

- In the case of the phallic presupposition of the male penis, it suffices to ask what the point of view of the female infant may be in noticing the problematic character of Freud’s conception. In fact, his answer to the question of the female is not “fear of castration”, but “envy of the penis” (Sigmund Freud, Gesammelte Werke V, p. 96). This formulation contradicts to a certain extent Freud’s ambition to formulate a universally valid theory of castration, since biological factors break into his theoretical field producing an unsurpassable asymmetry between the sexes.

- Jacques Lacan, La signification du phallus, in: Écrits, Paris 1966, pp. 685-695.

- Jacques Lacan, Ibidem, p. 690.

- Jacques Lacan, À la mémoire d’Ernest Jones : Sur la théorie du symbolisme, in Écrits, pp. 697-717, quotation p. 701.

- Jacques Lacan, La signification du phallus, in: Écrits, p. 703.

- For the metaphor of the Labyrinth in Lacan, see Lacan’s comments on the phallic phase in Le séminaire, livre VI: Le désir et son interprétation, Paris 2013, p. 151: “An impressively rich phenomenology renders the prerequisites visible that the subject needs to fully display his desire. We could reconstruct that in detail to the point of finding what I would call labyrinthine pathways into which the subject slides”. Lacan’s labyrinth is related to the manifold positions that the subject of desire will assume on the way to an impossible satisfaction, that is, “in the structural relation between desire and demand” (Ibidem).

- Alain Daniélou, Le Phallus, pp. 28-29.

- Alain Daniélou, Le Phallus, p. 25. The Sanskrit text reads: pradānaṃ liṅgamākhyātaṃ liṅgī ca parameśvaraḥ [“the primary germ is said to be liṅga, and the Supreme Being has the distinctive character of it”].

- This is how Daniélou understands the term ānanda [bliss], which he translates as “sensual pleasure” (Alain Daniélou, Le Phallus, p. 96).

- Alain Daniélou, Ibidem, p. 60.

- Daniélou also refers to the expression liṅga-dhāra when he speaks of the genetic code that is transmitted by reproduction (cf. Daniélou, Le Phallus, pp. 93-94), but that aspect is only analogically important to establish a parallel between the semen issuing from the human phallus and the universe issuing from Shiva’s liṅga – a parallel reinforced by Daniélou’s reference, by means of a quotation from the Chāndogya-Upaniṣad 2.13.1, to the sexual act as re-creation (cf. Daniélou, Ibidem, p. 34). It is only in the erotic experience stricto sensu, i.e. detached from its reproductive function and even from personalistic attachments, that this parallel can become concrete and pervading in the individual’s existence.

- “Why is the liṅga worshipped? Because it is the symbol of the permanent, of the archetypes disclosing the nature of the universal man, Purusha” (Alain Daniélou, Le Phallus, p. 112).

- Expressions like “the transfer to a new being of the ancestral heritage containing the archetypes that stem from the divine thought” (Alain Daniélou, Le Phallus, p. 34) seem to leave no doubt of Eliade’s influence on Jung, since for Eliade symbolic thought is not related to discursive reason but to an ontologically effective realm showing a drastic discontinuity in relation to history.

- For example, in the preface to the Torchbook edition of Le mythe de l‘éternel retour (1946), where Eliade writes the following: “For professor Jung, the archetypes are structures of the collective unconscious. But in my book, in nowhere [do I] touch upon the problems of depth psychology nor do I use the concept of collective unconscious. As I have said, I use the term archetype, just as Eugenio d’Ors does, as a synonym for exemplary model or paradigm, that is, in the last analysis, in the Augustinian sense” (Mircea Eliade, Cosmos and History: The Myth of the Eternal Return, New York 1959, p. ix.

- I use the verb ‘transgress’ in a specific (i. e. not at all negative) sense, which comes closer to Erich Neumann’s conception of the transgressive character of the archetypal field. ‘Transgressive’ is in fact a type of ‘extraneous knowledge’ that challenges the absolutist logic of the world created by the system of ego-consciousness. Cf. Erich Neumann, Die Psyche und die Wandlung der Wirklichkeitsebene, in: Die Psyche als Ort der Gestaltung, pp. 52-92, especially pp. 54, 56 and 66.

- In this respect cf. Jung’s first approach to the question of archetypes in Über die Archetypen des kollektiven Unbewusste (Gesammelte Werke IX/1: die Archetypen und das kollektive Unbewusste, Olten 1985, § 5, pp. 14-15), which is a re-elaboration of the homonymous text published in 1934 in the Eranos-Jahrbuch. Ultimately Eliade does 19 not add a metaphysical dimension to a psychological theory but rather objectifies the transdisciplinary implications of the Jungian conception.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Le Phallus, p. 25.

- I refer mainly to the so-called ‘visionary notebooks’, Liber Novus and The Black Books, published in 2009 and 2020, respectively.

- Alain Daniélou, Ibidem, p. 110.

- That is the sense of Lacan’s phrase “there is no sexual relationship [il n’y a pas de rapport sexuel]” (Jacques Lacan, L’étourdit (1973), in: Autres Écrits, Paris 2001, pp. 449-495, quotation p. 455).

- Cf. C. G. Jung, Gesammelte Werke 5: Symbole der Wandlung, § 146, p. 128.

- C. G. Jung, Erinnerungen, Träume, Gedanken, Zürich: Düsseldorf 2003 [first edition 1971], p. 18.

- C. G. Jung, Ibidem.

- C. G. Jung, Ibidem, pp. 18-19.

- C. G. Jung, Ibidem, p. 21.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Le Phallus, p. 41.

- Alain Daniélou, Le Phallus, p. 43.

- C. G. Jung, Erinnerungen, Träume, Gedanken, p.

- Alain Daniélou, Le Phallus, p. 53.

- Eugene Monick, Phallos: Sacred Image of the Masculine, Toronto 1987, p. 10. The specific and problematic character of this theory would deserve to be discussed at length, but such a discussion would exceed by far the framework of this essay.

- Eugene Monick, Ibidem, p. 13.

- In fact, there is neither of them in Monick’s life, since he grew up heterosexual and there was, in the context of that childhood episode, no reaction whatsoever on the part of his father.

- Cf. Johann Jakob Bachofen, Das Mutterrecht, Frankfurt 1978, pp. 47-48.

- The theory of the double phallus (solar and chthonic) can be found in Erich Neumann’s Ursprungsgeschichte des Bewusstseins (1949), but Neumann declares chthonic masculinity to be under the rule of the Great Mother (cf. Monick’s remarks on that aspect in Phallos, p. 59).

- Eugene Monick, Ibidem, p. 53.

- Eugene Monick, Ibidem, p. 29.

- Alain Daniélou, Le Phallus, p. 16. This thesis was expressed in previous essays, for example in Relations entre les cultures dravidiennes et négro-africaines, written in 1978 for a meeting at the UNESCO in Dakar (cf. Alain Daniélou, La civilization des differences, Paris 2003, pp. 151-165, especially pp. 157-159).

- Cf. Alain Daniélou, Le Phallus, p. 67.

- Alain Daniélou, Le Phallus, p. 29.

- Mircea Eliade, Méphistophélès et l‘androgyne, Paris 1962, p. 298.

- Alain Daniélou, Le Phallus, p. 34.

- Alain Daniélou, Le Phallus, p. 112.