Alain Daniélou

MANTRA: THE PRINCIPLES OF LANGUAGE AND MUSIC ACCORDING TO HINDU COSMOLOGY – SECOND PART

This essay appeared in the Cahiers d’Ethnomusicologie N°4, 1991. Alain Daniélou deals with the question of mantra from an integral point of view, bearing in mind metaphysics, cosmology, language, music and psychology. The first part was published in the Summer Solstice issue of Transcultural Dialogues (May 2019). This is the second part of the rather long essay, originally published in French.

Alain Daniélou at the Labyrinth in 1985 (photo by Jacques Cloarec)

Alain Daniélou at the Labyrinth in 1985 (photo by Jacques Cloarec)In the Kali-Yuga (the age in which we live), the path of music, the path of rāga, is regarded as more accessible than mantra-yoga, since it is not intellectual and active but rather intuitive and passive. These characteristics are in consonance with the present age, in which the feminine aspect is emphasized as the best means of self-realisation and access to spiritual values.

If we examine the organs used to manifest spoken language, we notice that, like all the organs of our body, the organ of speech presents symbolic characteristics. It is not by chance that our hand has five fingers, that each one of the fingers has three phalanges, that our body has certain proportions, that our eye is solar and our ear labyrinthine. The organ of speech has the form of a yantra. The arch of the palate is shaped like a demi-sphere, similar to the celestial one. There, we find five special points of articulation which enable us to pronounce five main vowels, two secondary and two resulting ones, all of which are symbolically related to the nine planets, two of which are normally invisible.

The fifty-four sounds forming the stuff of speech are classified in a mysterious formulary called the maheśvara sūtra, which, by means of a hierarchy of articulate sounds, mirrors the emergence of the Universe from the Divine Verb. Nandikeśvara’s commentary on the maheśvara sūtra (which pre-dates Pāṇini’s grammar in the V century BCE) explains this particular classification of sounds and its fundamental meaning from a very abstract point of view, but we can find applications of it in all aspects of manifested reality, for example at the basis of every science. Nandikeśvara also points to the correspondences between vowels in language and sounds in music. The nine (seven main and two secondary) vowels are seen as parallels to the musical notes, the planets and the colours. The parallels between the notes of the musical scale and the vowel sounds of articulated language are self-evident – and incidentally they have the same name: svara.

In his Rudra Ḍamaru, Nandikeśvara establishes correspondences between vowels and musical notes in an unexpected way, since he does it on the basis of the tetrachord instead of the octave. Sa, the tonic devoid of fixed value, which we call for the sake of convenience “do” (c), corresponds to the vowel a, which is the basis for all other vowels. In fact, the tonic forms the basis on which all other notes depend and to which they owe their existence. “Re” (d), called ṛṣabha (the bull), corresponds to i, that is, to energy (śakti). Ga, e-flat, corresponds to u, which in turn stands for the materialised principle – source of life, sensation and emotion. These three basic notes are surrounded by e natural, which corresponds to the vowel ë (as in the French “je”) standing for the personified god, whereas in the other tetrachord, b natural corresponds to ü (as in the French “tu”), which stands for māyā, the illusion of matter. “Fa” corresponds to the vowel e, the principle endowed with its power, its śakti, represented by the moon, the female symbol. Sol corresponds to o, the principle indwelling its own creation, the symbol of which is the sun, the male principle. It is therefore the note “sol” that corresponds to the syllable AUM. Subsequently we have the note corresponding to the open vowel e, which stands for the mirror of the universe upon its principle. This is the path of reintegration or yoga. Open o corresponds to b flat major and evokes the universal law (dharma), determining the development of the world like a fetus in the divine womb.

We can see that the essential basis of musical expression is focused on the first trichord: c, d, e flat. C is the neuter base from which all the intervals can be constructed. D (9/8), arising from the number 3, stands for the śakti and expresses movement, strength, aggression. It is with e flat that the element of life, sensitivity and emotion appears.

Consonants are shaped at the same five points of articulation as vowels by efforts directed either inwards or outwards, either by projection or by attraction, for example k outwards and g inwards, or t outwards and d inwards. Consonants can be de-aspirated (t) or aspirated (th).

Primordial language, according to Sanskrit grammarians, was essentially monosyllabic. This is the language of mantras, from which all other languages have emerged.

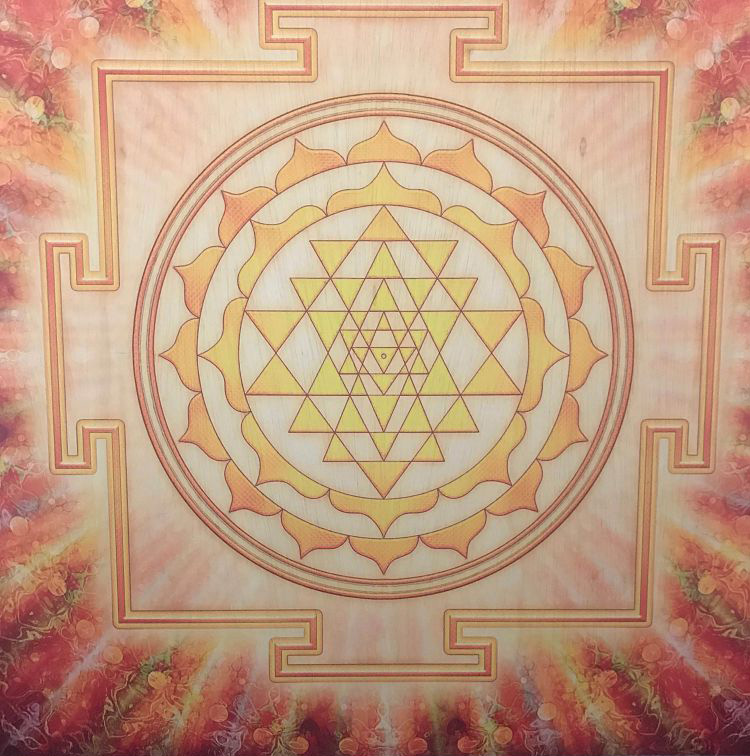

Śrī Yantra, a sacred diagram with multiple meanings, among which that of a simultaneously luminous and sonic vibration channeling the universal manifestation of the ultimate principle, whose first determination is symbolised by the central point.

Śrī Yantra, a sacred diagram with multiple meanings, among which that of a simultaneously luminous and sonic vibration channeling the universal manifestation of the ultimate principle, whose first determination is symbolised by the central point.Every language consists of monosyllabic entities forming autonomous elements added to each other to compose complex words. The meaning of a word is the sum of the meanings of the different syllables. Primordial language, according to Sanskrit grammarians, was essentially monosyllabic. This is the language of mantras, from which all other languages have emerged. In this language, sounds – due already to their point of articulation and the nature of the effort to produce them – help represent fundamental principles. The language of mantras can therefore be seen as the true language in which sound is the exact representation of a principle. In this sense, haṃ, the guttural sound stemming from a, is the mantra of ether, the latter being the principle of space and time as well as the sphere of the sense of hearing. Yaṃ, stemming from palatal i, is the mantra of air or gaseous state corresponding to the sense of touching. Raṃ, stemming from cerebral ë (ṛ), is the mantra of the igneous state or fire, which corresponds to the sense of sight. Vaṃ, stemming from labial u, is the mantra of the liquid state or water, sphere of taste. The last demi-vowel, dental l, stemming from ü (lṛ), constitutes a separate group. The syllable laṃ symbolises the solid state or earth, corresponding to the sense of smell, which is also perceptible by all other senses. In the organ of speech, the syllable aum contains guttural a, labial u and cerebral resonance m. This constitutes a triangle circumscribing all possibilities of sound articulation, that is, the totality of language, and thus everything that can be expressed through language. Its multiple meanings are explained in the Tantras and in certain Upaniṣads, especially in the Chāndogya. The Maheśvara Sūtra explains the basic sense of all possibilities of articulation and shows how – upon this basis –roots can be built that will represent the most complex ideas through their multiple combinations. The different possibilities of pronunciation concerning vowels, for example long or short, high or low, natural or nasal, make a total of 162 different vowel sounds that can be modelled with the aid of five consonant groups with airflow or occlusion, with or without aspiration, making a total of 33 consonants. This group constitutes the totality of the material susceptible of being used in spoken language. This shows that by using Nandikeśvara’s method we can explain the formation of words in each language.

Musical language seems in a certain way more abstract and more primordial than spoken language. It consists purely of frequency relationships and vibrations that can be traced back to purely numerical relations. This is a direct image of the process of manifestation out of the Verb (corresponding to the origin of the world), that is, of energy-codes and pure vibrations of which all elements are constituted. The mathematical principles on which musical language rests can be compared to the geometric symbolism of yantras. The latter are diagrams evoking the fundamental energy principles or deities on which all sacred art is based. The fact that we are unable to recognize accurately and reproduce the fifty-four different sounds within an octave is not accidental, but rather due to the fact that we can grasp only certain simple numeric relationships corresponding to different combinations of factors 2, 3 and 5. In Indian music, we use only twenty-two of these sounds, or twenty-four if we count the tonic and the octave, but only in relation to one single basic sound. As soon as the basic sound is altered, other intervals appear.

The sounds of musical language relate to affective elements and have a direct impact on our psyche. They create different emotional states called rasa, such as love, tenderness, fear, heroism, horror and peace. There are correspondences between our different forms of perception and the structures of matter and life, since both realms are interdependent. We can therefore establish parallels between colours and sounds, or planets and musical notes. This is no arbitrary comparison, but an observation of identical characteristics evoking cosmological principles related to the very nature of the world. Whether we represent the origin of the world as a cry, or a word in the theory of the Verb, or as an explosion of energy (like the big bang), the question remains the same. The world develops within the limits of its own possibilities according to a plan, a kind of genetic code. All its aspects have parallel structures that can be traced back to a common origin, and it is through these parallelisms that we can have an idea of the nature of the world, since they are the object of all research and all veritable science. Perception and its object are strictly coordinated and stem from the same principles. They are made for each other within a pattern of intense interdependency, which is why we have a distinct sense to perceive each one of the states of matter or the elements.

Geometric figures forming yantras present a system of symbolic relations parallel to that of musical and articulated sounds (mantras). The parallels that can be established between colours and musical notes are complex, since their difference consists of śruti or micro-intervals. They depend on the relationships between sounds and not on their absolute pitch. In modal music, we must first consider the invariable notes forming the framework of rāgas. If we consider “do” as tonic, like “sa”, it appears as multicolour and corresponds to the point in the yantras, to the nasal resonance or anusvāra in the mantras.

The triangle with the tip at the top is the symbol of fire, in this case considered as a male principle. It corresponds to the colour red, to “re” in the range of music and to the vowel i of the mantras. The triangle with the tip at the bottom is the symbol of water, here considered as a female principle. It corresponds to the colour of pearl, the moon, the note “fa” and the vowel ü (lṛ) of the mantras. The circle, a solar symbol, corresponds to the note “sol”, to the colours black or golden and to the vowel ë (ṛ) of the mantras. The square, symbol of the earth, has a yellow colour, evokes the sense of smell and corresponds to the note “la”.

All the other notes of the scale are mobile and, depending on their śruti, their exact relationship with the tonic corresponds to a colour of the śruti category, the śruti-jāti, to which they belong and which determines their expressive value, the feeling or evoked rasa.

The śrutis are divided into five categories corresponding to different rasas or genres of emotion evoked by them. They can therefore evoke a feeling of quiet joy (blue), aggression (red), eroticism (orange), vanity (green), confidence (yellow), melancholy (grey), fear or repulsion (purple). Thus the “mi” or third harmonic is blue, whereas the “mi +”, obtained by fifths, is orange. The superimposed triangles that we call the seal of Salomon represent the union of opposites, the union of sexes, also like the cross, whose vertical line is the symbol of fire (male principle) and the horizontal line that of water (female principle). This symbol corresponds to the relationship of “sol” (3/2) and of “fa”, a female symbol (with a relationship of 2/3). The starlit pentagon is the symbol of life and the sign of Shiva. It corresponds in music to e flat major and to the series of expressive intervals in which the factor 5 is represented and of which the harmonic minor third is the clearest expression.

The language of mantras can be seen as the true language in which sound is the exact representation of a principle.

It is the subtle differences in its sounds that enables music to have a profound psychological effect. Following the śrutis for a given scale, every melodic form built upon this scale will have either a soothing and pacifying effect or a stimulating one. It is no coincidence that military music styles use instruments like trumpets, which can only emit sounds of the red series: aggressive and stimulating.

To achieve a strong and lasting psychological effect, the modal system (found in Indian or Iranian music) is by far the most efficient. The reason is simple: the basic sound, or tonic, is fixed during a musical performance, therefore each interval, for example a third or a fifth, will always correspond to the same sound, to the same frequency. This sound repeats itself, returns and is permanently charged with the same meaning. Such repetitive action has profound effects. If it happens to be a soothing blue third, listeners will little by little feel relaxed. If, on the contrary, it is an aggressive third perpetually stimulating their ear, the listeners will step out of their apathy and feel more energetic and vigorous. Sound categories work in this sense like drugs, and precisely for this reason the modal system enables real therapeutic action to be applied in music-therapy with great success – of course on condition that the sounds be emitted with great precision. For this very reason, the sounds of contemporary music are sometimes very scary.

The question that arises is the following: are we confronted with arbitrary approximations based on coincidence or rather with constants revealing essential aspects of the nature of manifestation? We know in any case that we are dealing with the limits that shape our perception of the world, but what for us seems an unresolvable question does not pose any problem for Hindu theoreticians. Such correspondences enable them to explain the power of mantras as well as the psychological effect of musical intervals. It is easy to regard these theories and the correspondences put forward by them as arbitrary – as has occurred many times. It is also true that such principles are sometimes misunderstood and applied in a way that oscillates between the whimsical and the absurd. We can very well bring to mind the example of the Chinese philosopher who, knowing that there were five elements, defined them as earth, water, fire, silk and bamboo. By means of the yogic experience, we can verify the reality of certain fundamental factors, and in the practice of music we can experience the psychological effect of sounds and the connexion between our perceptions and numeric factors independently of any theoretical approach.

Indian cosmology as a method does not begin with sense experience in order to ascend to the principles, but, on the contrary, takes research on universal principles as a starting point, and subsequently finds their application to the different aspects of the visible and invisible world. This approach is called Sāṁkhya, “study of the measurable”. This definition has something in common with the idea of science according to contemporary scholars and philosophers. If applied to articulated or musical language, it establishes existing connexions between sounds, ideas and emotional states, which no other method can achieve. The study of parallels between different aspects of the world can also open a channel of communication (through the magical power of sound, gestures and symbols) between the different states of being, not only among humans but also between humans and non-humans (spirits and gods). Ultimately it can lead the practitioner beyond the limits of the senses and attain, in the innermost part of ourselves, transcendent reality, the deepest and most essential aim of yoga.