Dana Rush

Art Historian at the University of Strasbourg (France)

THE IDEA OF “INDIA”, THE SEA, AND SHIVA IN WEST-AFRICAN VODUN

There are many ideas of “India”. In Mami Wata Vodun practice in coastal Togo and Bénin, the idea of India is not simply one of geography or theology. Rather, “India” offers boundless aesthetic and spiritual opportunities in both time and space, extending beyond the visible, tangible, human domain into a world where eternity and divine infinity subside into the here and now.

All photos belonging to this article are taken by the author.

This essay stems partly from previously published works.

See Rush 1999, 2008ab, 2009, 2013, 2016

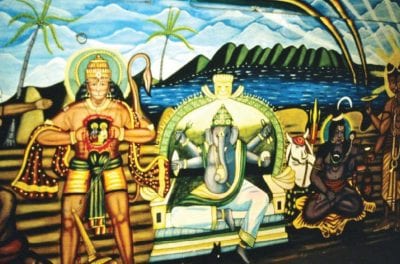

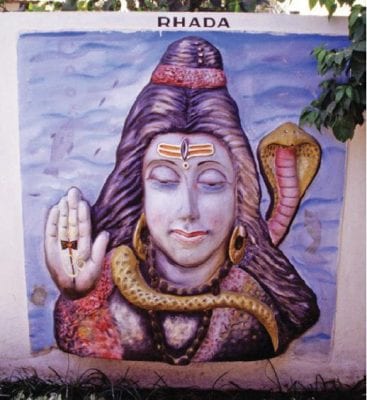

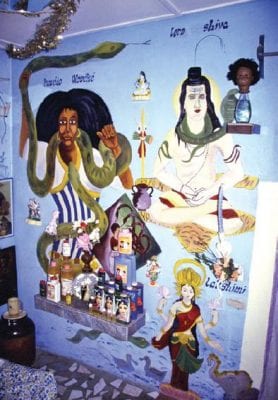

Fig.1 Wall mural with Mami Wata and Shiva Mami Dan. Painted by Joseph Ahiator.

Lomé, Togo, December 1999

This essay, stemming from decades of research on West African Vodun, demonstrates how and why this idea of “India”1 has been seamlessly absorbed into Vodun practice through exploring the profound impact of the sea and its India spirits on coastal Mami Wata Vodun. Not only is the sea regarded as a source of vast spiritual strength, but it is also known to bring powerful foreign spirits from faraway lands for local veneration. One such land is a mythologised “India”, represented concretely by images and objects imported from India and used in Vodun veneration and with an abstract reference to the sea. I demonstrate this influence through Indian chromolithographs (in paper or digital form), examining how and why these foreign prints have been absorbed into Vodun practice, how a single artist/adept and one priest have adopted and adapted these images into their own local visual theologies, and how Hindu gods and goddesses, in conjunction with the sea, fully inform Mami Wata Vodun. The following exploration sets the backdrop for a short reflection on time and space travel with a focus on Shiva Mami Dan (right side of fig 1).

Vodun and Mami Wata

Vodun is the predominant religious system in coastal Bénin and Togo organised around a single divine creator and an uncountable number of spirits, including Mami Wata. Much more than a single spirit, Mami Wata is an entire pantheon. For any new problem or situation that arises needing spiritual intervention or guidance, a new Mami Wata spirit arises from the sea. The pantheon of Mami Wata sea spirits represents wealth, beauty, seduction, desire, fidelity, femininity, human anomalies, and modernity, among other things. Veneration of these sea spirits is reliant upon imported chromolithographs, which have come to represent “India Spirits”.

Known commonly as the Vodun of wealth and beauty who commands the sea, Mami Wata is recognized for her allure as a source of potential wealth, both religious and economic. The Mamisi, “wives” or devotees of Mami Wata, venerate their own demanding spirits from the sea as well as new spirits addressing the needs of a quickly changing society with an aesthetic and spiritual flair that not only includes “India Spirits”, but requires them. Life’s recently introduced or previously unfamiliar uncertainties of modernity are often embraced and made sense of through Indian imagery used in Mami Wata religious practice.

The Sea

Along this West African coastline, the sea — with its force and intensity, potency and vigor, and unpredictable temperament — is more than anthropomorphic: it is deistic. The sea gives and takes, it sustains life and it can kill. Importantly, the sea offers the most fervent spiritual authority along this coastline, the abode of Mami Wata.

India Spirits are invariably from the sea and deeply associated with an idea of India, rendering “India” and the sea synonymous; they are known yet unknowable, a paradox mediated through veneration. The terms “the sea” and “India” are often used interchangeably regarding Mami Wata Vodun, especially in reference to India spirits. Whenever I inquired of the origins of India spirits, the answer was invariably the sea, often with an arm gesturing in the direction of the coast. It is not uncommon to see the words “Sea Neva Dry” painted on Mami Wata temples known for their India Spirits, as a reference to the fact Mami Wata and her India Spirits will always exist because, unlike rivers or lakes, the sea will never dry.

This Atlantic coastline simultaneously effaces and defines the meeting of land and sea: that is, where Africa and “India” merge. It is a place where awareness can be Janusfaced, and where space and time can and do alter. Because the sea is as deep as one’s own imagination, and vice versa, the breadth of India Spirits, associated India arts, and India experiences is inexhaustible. At the same time, this coastline – liminal as it may be – is a gateway to centuries of very real transatlantic interactions and exchanges from before the slave trade to the present. In effect, along this West African seaboard, two simultaneous processes occur for which the sea functions as both a passageway to vast cultural and spiritual potential and an exceedingly lucrative portal to centuries of travel and commodities exchange.

Chromolithographs of India Spirits

Even though the idea of India in Mami Wata Vodun practice probably emerged no earlier than the 1950s, it is the ancient, essentially elastic, conceptual system of Vodun, which has allowed it to thrive. The integration of Indian images into Vodun epistemologies is exemplary of the overall incorporative sensibilities of Vodun. Although, at some point, these images were newly seen, they have been approached in Vodun as something that was already known and understood; as something already familiar within the Vodun pantheon. These images of Indian gods have not been combined with, but rather they are, local gods.

Not only is the sea regarded as a source of vast spiritual strength, but it is also known to bring powerful foreign spirits from faraway lands for local veneration.

Fig. 2. Market stand with the image of Sathya Sai Baba to the right of an image of Shiva. Asigamé market. Lomé, Togo, January 2000.

Elaborately detailed Indian chromolithographs have been incorporated into Mami Wata veneration precisely because of the open-ended structures and richly suggestive imagery that allow them to embody a wide range of diverse ideas, themes, beliefs, histories, and legends. The prints themselves serve as both instructions and vehicles of divine worship; they suggest rules of conduct, recount legendary narratives, and act as objects of adoration. The specific animals, foods, drinks, jewelry, body markings, and accoutrements found in these chromolithographs have become sacred to the Vodun spirits represented.

Such prints are available for purchase at local markets in Togo (fig 2). Others are available from local Indian stores in the form of decorative promotional calendars. In the past decade, the vast internet image archive has amped up accessibility to anyone with a smart phone who seeks visual representation of Hindu and other Indian deities or religious figures. These readily obtainable images, either in print or digital form, go hand-in-hand with Mami Wata artistic and spiritual propensities: the super-abun-dance of flowers, gold, jewels, coins, and other luxurious items surrounding the spiritually charged deities depicted in many of these images function as links into particular India Spirit sensibilities. For example, a three-dimensional Mami Wata shrine in a Vodun temple, overflowing with bottles of perfume, powder, fruits, candies, incense, cowry shells, etc. can be represented by a chromolithograph or even an image on one’s cell phone, as an ethereally collapsed, ready-made two-dimensional shrine. In Vodun, the immediate visual impact of these images provides an aesthetic and spiritual syn-esthesia that quickly induces a divine presence. In other words: these images work. Visual and spiritual saturation in an economic and porta-ble, even digital form, attests to the potential of chromolithography in Vodun.

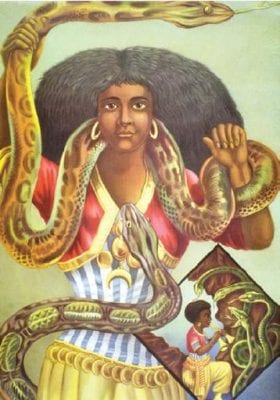

Fig. 3 Mami Wata lithograph. Author’s collection.

By far the most popular chromolithograph representing Mami Wata is based on a latenine-teenth century chromolithograph of a snake charmer in a German circus (fig 3. for a complete history of the image see Drewal 1988). This Mami Wata image, painted on the left side of figure 1, and found in most Mami Wata temples, is only one of the many representations found in Mami Wata religious practice. There are also representations of figures from the Ramayana and other Hindu lore and world religious histories, including prints of Rama, Sita, Hanuman, Shiva, Dattatreya, Hare Krishnas, Shirdi and Satya Sai Baba, the Buddha, Guru Nanak, alBuraq, the Pope, Eve, Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, and various Christian saints. Secular images such as animals and floral arrangements are common as well, and also influence the content and appearance of shrine offerings.

A few examples of India Spirits in Mami Wata Vodun

In talking to Vodun priests, priestesses, and sellers of India Spirit images through the years, I learned quickly that my basic knowledge of Hindu, Sikh, and other deities represented in these prints was not applicable to my attempts at identifying or understanding the wide range of Vodun India Spirits. Initially, each time I asked someone to share with me the name of the deity represented in a print, I was told Mami Wata. I desired more precision so I started asking questions differently. Instead of asking who was represented in the image, I identified the image with its standard Indian name asking if that was correct. I was quickly corrected and given the Vodun name.

Fig 4. India Spirit wall mural painted by Joseph Ahiator in Mami Wata temple vin Cotonou, Bénin, January 1995.

For example, at a market stand I visited often in Lomé, Togo, what I interpreted as Krishna with Radha was deemed incorrect. Instead, I was told that the image represented Mawu-Lisa, the androgynous dual deity in the Vodun pantheon. What I identified as the Sikh image of Guru Gobind Singh Ji, I was told was the Vodun spirit Ablòlisodji, or Liberty on a Horse. What I was certain was the Buddha, I was corrected and told that the image represented the Vodun spirit Confusci. Once again, I was quickly corrected when I asked about an image of Durga whom I was told was Mami Sika, or Mother of Gold. The image of Lakshmi usually retained the In-dian name, though she was sometimes simply called Mami Wata.

After much trial and error, I finally understood that depictions, in general, of Krishna with snakes –either playing a flute while dancing with a snake or standing on top of snakes, for example– were not, in fact, Krishna, but Edan/ Dan, the serpent Vodun. (Edan is the Ewe/Mina word and Dan is the Fon word for snake; they are mutually understood in both languages.) I slowly learned that just about any India Spirit print, containing one or multiple snakes, represented the Edan/Dan. Nonetheless, each time I thought I finally understood which Vodun spirit was represented, I learned otherwise. For example, when I identified a four-armed Krishna with crossed legs on a throne of coiled snakes as Edan, I was, once again, corrected. This image, I was informed, is called Aida Wedo, shortened from Dan Aida Wedo, the rainbow serpent Vodun, part of the overarching group of Edan/Dan spirits, but not the same. In fact, many images were interpreted slightly differently depending on with whom I was speaking. After years, I learned to anticipate a range of names for each print.

Much more than a single spirit, Mami Wata is an entire pantheon. For any new problem or situation that arises needing spiritual intervention or guidance, a new Mami Wata spirit arises from the sea.

A few examples of Mami Wata India Spirits

Ghanaian/Togolese artist Joseph Kossivi Ahiator (1956-2011) was the most sought-after India Spirit temple painter in Bénin, Togo, and Ghana. He consulted his own array of chromolithographs when commissioned to paint Vodun temples, and then elaborated the images based on his own dreams coupled with the dreams and desires of the temple owner. Ahiator, a Mami Wata adept himself, was very connected to the sea. He was born with India spirits and he visited India often; sometimes in his dreams, sometimes while at the beach. These travels thoroughly informed his art. In the early 1990s, Ahiator created his first India Spirit mural in a Mami Wata temple in Cotonou, Bénin (fig. 4). Around the same time, he created a similar mural in Lomé, Togo. Neither of these murals exists today due to the wear and tear of time. A short discussion of three of these Mami Wata India Spirits illustrated in figure 3 follows.

Hanuman/Gniblin

Hanuman –commonly known in the Ramayana as Prince Rama’s loyal servant and protector who carries the essence of Rama or Rama and Sita with him wherever he goes— is some-times referred to as Gniblin Egu in Mami Wata

Vodun. Featured prominently in the centre of Ahiator’s mural (left side of fig. 4) is the powerful half-animal, half-human super-being called Gniblin Egu. Gniblin is famous for his power of Egu, the Ewe/Mina cognate of the Yoruba Ogun, and the Fon Gu, deities of iron, war, and technology. Gniblin Egu is credited with teaching iron technology to people. Although Gniblin Egu comes from the sea, Mami Wata adepts hold that he lives on the road and is associated with traffic accidents. He can travel anywhere and his fiery tail is seen as he flies through the air. If he is angry, he can burn a whole city, and he can use his tail to beat witches. A popular chromolithograph shows Hanuman responding to the challenge that he, in fact, does not have the capacity to carry Rama and Sita with him wherever he goes. In response, Hanuman tears open his chest and to the bewilderment of his onlookers, reveals Rama and Sita within. Likewise, Gniblin Egu responded to a similar challenge in response to the allegation that he did not, as he claimed, carry his deceased parents with him. He, too, tore open his chest to reveal his deceased parents and the truth of his claim. Given the importance of ancestral veneration in Vodun, Gniblin Egu becomes here both a Vodun spirit and an ancestral shrine.

Ganesh/Tohosu

To the right of Gniblin Egu is Tohosu Amlina (centre of fig. 4). Tohosu is the Fon Vodun of royalty, human deformations, lakes, and streams. The painting of Tohosu is based upon a chromolithograph of Ganesh, the elephant-headed, potbellied Hindu god of thresholds, beginnings, and wisdom, who removes obstacles.

The image of Ganesh visually encapsulates the Fon spirit of Tohosu: royal (surrounded by wealth, corpulent from luxurious dining) and super-human (a human with an elephant’s head and four arms). Although Ganesh is not known to be associated with lakes or streams, Mamisi often recognise the blue background of many Ganesh images as representing the sea, his home in the Mami Wata pantheon. A Mamisi with the spirit of Tohosu Amlina may never kill rats, for this creature, often depicted with Ganesh, has become sacred to the spirit’s devotees (seen at his foot). Not only do Hindu chromolithographs suggest and reify characteristics already inherent in local gods, but they also introduce, influence, and change already-estab-lished, albeit organic, religious practice.

Shiva/Mami Dan

To the right of Tohosu in Ahiator’s mural is Shiva Mami Dan also called Akpan or Ako Ado, whose job it is to clear the path for Mami Wata. Shiva Mami Dan, was born with snakes draped around his neck and arms and almost always appears that way. He is known to be old as the sea and his job is to clear the path for Mami Wata.

This depiction of Shiva Mami Dan comes directly from one of the best-known illustrations of Shiva, called Shiva-Dakshina-Murti or Mahayogi (right side of fig. 4). The illustration shows Shiva as an ascetic in deep meditation atop the Himalayas. He is wearing a simple loincloth and is seated on a tiger skin, which Mamisi say is the panther who clears the path for Shiva Mami Dan, and in turn, Mami Wata. He is often depicted with a drum hanging from a trident next to him; he uses his drum to call other spirits to come to dance, pray, and celebrate with him.

The water springing from Shiva Mami Dan’s head is critical. As an integral member of the Mami Wata pantheon, he is highly associated with the sea, and, in turn, India. He, however, cannot travel to India without having access to the sea, which he needs for his survival. Mami Wata thus blessed him with an eternal spring of seawater emerging from his head. The seawater circulating through Shiva Mami Dan is his life source without which he cannot emerge from the sea to travel. Accordingly, the only way Shiva can spend time in the Himalayas is because of this gift from Mami Wata merging, once again, Africa, India, and the sea.

Representations of Shiva Mami Dan are on the upsurge and he is now more commonly known simply as Shiva. The name Shiva is often pronounced and spelled Chiva. This pronunciation might have a complementary connotation, which links closely to Mami Wata sensibilities. Chiva sounds similar to “echi ne va,” when spoken quickly, which means in Ewe/Mina “money will come.” In a recent WhatsApp correspondence (July 2019), I was told by a young lady currently going through initiation into Shiva Vodun that “Chiva is a Dan Vodun who is now found within all of the Vodun because he brings money.” Whether Shiva is recognized within all Vodun is unlikely, but these perspectives suggest that Shiva Mami Dan’s rising allure is perhaps linked to the implication that money will come, as perceived in the pronouncement of his name.

Much more than a single spirit, Mami Wata is an entire pantheon. For any new problem or situation that arises needing spiritual intervention or guidance, a new Mami Wata spirit arises from the sea.

Fig 5. Shiva (Rhada) bas-relief wall mainting at entry of Gilbert Atissou’s Mami Wata painting. Aného, Togo. February 2000.

Shiva Mami Dan / Shiva Rhada / Lord Shiva in Aneho, Togo

Aneho, Togo, a coastal town known for its high concentration of Mami Wata devotees, boasts a strong and longstanding tradition of India Spirits associated with Mami Wata. After a few unremarkable exploratory visits to Aneho, I happened upon an extraordinary Vodun temple. Inside, bas-reliefs of Shiva and Lakshmi flank the doorway that allows entrance to the heart of Mami Wata Vodun priest Gilbert Atissou’s compound (d. 2009). He became a friend of mine and was delighted to answer any of my questions about the presence of “India” in his compound.

After many long conversations with Atissou, I learned that he was always drawn to Indian gods and their power to control the sea. He was especially passionate about Shiva. He would travel to Lomé, Togo to seek out anything he could find related to India and buy whatever he could afford –objects and images—mainly in Indian owned stores. His first purchase was a wooden staff topped with what he called a Shiva trident, also known as apia in Vodun. Atissou said that during the 1960s, he began spending hours upon hours at the beach, where he would journey to India, and find himself surrounded by “beautiful things”. He would spend months at a time in India during these hours along the coastline of Aného. He reported these “voyages” to his Christian family, and as Atissou’s obsession with the sea and his curious behaviour grew, his family took him to a Christian Celeste church in order to exorcise these “demonic” spirits from his system. Celestial Christians, however, deemed his India Spirits so powerful that they advised him to nurture them rather than eliminate them. Thus he began incorporating Indian items into his own Mami Wata veneration. Similarly, I was told throughout the years that India Spirits are the most powerful in the world – more power-ful than Vodun, more powerful than Jesus, and that once you have them, you must take good care of them.

Fig 6. Wall painting in Gilbert Atissou’s Mami Wata temple.

Aného, Togo, February 2000.

I inquired about the bas-relief mural of Shiva outside the main courtyard entrance (fig. 5). Atissou explained that “RHADA,” painted at the top of the wall composition, is one of the many names given to Shiva because, as with most Vodun spirits, there are times when it is inappropriate to state the spirit name outright. I then noticed that the background colour of the wall was light blue, and that there were fish and a turtle swimming within. “Is he underwater?” I asked. “Yes”, Atissou conformed, “he is in India”. We looked at various other wall paintings throughout his compound, mainly of Shiva and Lakshmi, while Atissou explained that Shiva is king of the underwater world and Lakshmi is a version of Mami Wata. Atissou then showed me his shrine dedicated to Shiva. What appeared to be a very typical Vodun shrine was, in fact, dedicated to Nana-Yo, another Vodun name for Shiva (fig. 6). In front of the shrine’s door, there was, according to Atissou, a carved yoni receptacle representing the female principal and origin of Hindu creation, which was there to receive offerings.

Fig. 7 Shiva shrine in Gilbert Atissou’s Mami Wata temple. Aného, Togo, February 2000.

From there, Atissou led me across the compound –whose walls were covered by paintings of Shiva interspersed with lily pads– into a shrine room he called India with four fully decorated walls covered with India Spirit paintings and smaller Hindu statues and chronolithographs mounted on the walls next to the paintings. One wall (fig. 7) had depictions of Lord Shiva and Lakshmi on the right side with Mami Wata (called Houédo Wouéké) occupying the left side of the mural. He explained that the walls in this room were blue because, once again, we were in India. He then pointed out the fish and other aquatic animals on the bottom of the mural equating India with an underwater realm.

He next led me through a back door into a more ostentatious shrine room brimming with post-ers of Indian gods, perfumes, powders, alcohol, candles, statuettes, stuffed, plastic, and ceramic animals, and other spirit representations. To Atissou, his India temple represented a consid-erable financial investment, but, in conjunction with prayers and ceremonies, his temple offered him access to powers unattainable by any other means. These items are spiritual status symbols, and most importantly, they made things happen and provided him the security he needed.

Since Atissou’s death in 2009, his daughter, Gagnon (“money is good”) whom he had trained, has been in charge of the temple. By 2014, the temple had fallen into disrepair. The last time I visited in 2016, she had refurbished a bit. The original paintings are still there, but they have been painted over with much brighter, louder colors than the originals, and the ambiance no longer captures the sense of beauty and tranquility that made this temple her father’s India haven.

Deep Dive: India Spirits in Time and Space

Both Joseph Ahiator and Gilybert Atissou, with their all-consuming dedication to India Spirits and the sea, were virtuosos at expanding and collapsing time and space in complete harmony within the world of Vodun. How could they condense weeks, months, and perhaps years and thousands upon thousands of kilometres, forward and backward, again and again, so effortlessly? How, in fact, could they spend months in India during an afternoon at the beach?

I had always appreciated their creativity of expression regarding their experiences, which I knew were not possible for me. I never doubted whether or not these travels were real. I simply accepted them. However, I never understood them. For me, and for a large part of the Western world, space and time are linear and predictable. We tend to like predictability and we fall for its illusion. The world of Vodun defies predictability because Vodun is pure potential; non-quanti-fiable and infinite. Vodun has tools to help us understand the enormous potential of unpredictability. These tools guide us in accessing the past and future through which time and space are, by default, merged in the present moment. Images of Shiva, and other India Spirits, animate Vodun’s superpower of accessing and allowing instant access to disparate and simultaneous experiences in time and space seamlessly, with no incongruence or disbelief. Shiva Mami Dan in conjunction with the sea is but one example. Afa divination is another. Trance possession is yet another. These powers are available to people, like Ahiator and Atissou, who can let go of the illusions of both predictability and linearity and fully and freely ride the infinite potential that surrounds them.

Ahiator and Atissou, even though their lives were, at times, precarious, did not live in fear or want. In their world of Vodun, where everything is possible, they did not think “what if?” or “then what?” Instead, they followed their paths as they unfolded. They lived in full faith and overwhelming spiritual abundance. Vodun offered this to them, they accepted, and their India Spirits delivered, serving as passports to space and time travel that few experience.

1 I picked up the term “India Spirits” from Ghanaian/Togolese artist Kossivi Ahiator (later mentioned in the essay). He was my first introduction to these spirits, and I spent a lot of time with him over the years. But, he spoke very broken English, so he referred to his images and his paintings as “India Spirits”. He was the first person who told me that he was “born with India Spirits”, so I just kept using that term without even thinking about it.

Sources mentioned

Drewal, Henry J. 1988. “Performing the Other: Mami Wata Worship in Africa.” The Drama Review 32(2):160-85.

Rush, Dana. 1999. “Eternal Potential: Chromolithographs in Vodunland.” African Arts, Winter, 32(4), 60-75, 94-96.

—–. 2008a. “The Idea of ‘India’ in West African Vodun Art and Thought,” in India in Africa, Africa in India: Indian Ocean Cosmopolitanisms, edited by John Hawley, Bloomington: Indiana University Press 2008, pp. 149-180

—–. 2008b. “Somewhere Under Dan’s Rainbow: Kossivi Ahiator’s ‘India Spirits’ in his Mami Wata Pantheon,” in Sacred Waters: The Many Faces of Mami Wata and Other Afro-Atlantic Water Spirits, edited by Henry John Drewal, Indiana University Press, pp. 466-476.

—–. 2009. Trans-Suds: Imaginaires de l’ ‘Inde’ dans l’art, la practique et la pensée Vodun d’Afrique de l’Ouest,” Journal Politique Africaine, éditions Karthala, No. 113, March, pp. 92-119.

—–. 2013. Vodun in Coastal Bénin: Unfinishes, Open-Ended, Global, Vanderbilt University Press, Nashville, pp. 87-109.

—–. 2016. “Imaginaires de l’« Inde » dans le vodun d’Afrique de l’Ouest,” in D’Afrique en Asie, d’Asie en Afrique Universitaires de Rouen et du Havre (PURH), pp. 85-106.