Adrián Navigante

Director Alain Daniélou Foundation Research and Intellectual Dialogue

FOREWORD TO THE BENGALI EDITION OF GODS OF LOVE AND ECSTASY: THE TRADITIONS OF SHIVA AND DIONYSUS

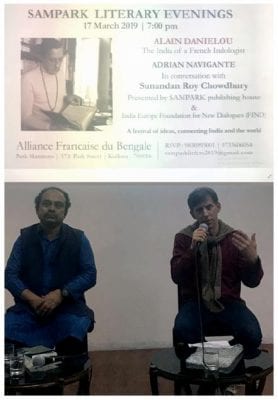

The following text is a slightly modified version of Adrián Navigante’s foreword to the Bengali edition of Alain Daniélou’s Gods of Love and Ecstasy: The Traditions of Shiva and Dionysus, recently published in Kolkata, India. The book was presented in March this year at the Alliance Française of Kolkata, hosted by the cultural program “Literary Evenings at Sampark”, followed by a discussion on Alain Daniélou’s thought in which Adrián Navigante and Sunandan Roy Chowdhury (Director of the publishing house Sampark and Alain Daniélou Foundation’s grantee 2018) shared their ideas with the audience.

Sundanan Roy Chowdhury and Adrián Navigante at Sampark Literary Evenings, 17 march 2019.

photo by Amanda Viana de Sousa

This book, which first appeared in 1979, is above all an archaeology of religious experience, and for this reason it is perhaps worthy of an attentive reading, especially in our own time. A study of Shiva and Dionysus would be impossible today, mainly because religious comparatism, which was quite acceptable – even beyond evolutionist parameters – after the Second World War, is now suspected of presenting arguments too general for the demands of specialized research and elements taken out of context and over-interpreted out of recognition, but also because one of the main ideas of Alain Daniélou’s book is about a primordial religion, a kind of trans- or pan-cultural substratum related to the forces of Nature and necessarily leading to a radical affirmation of Life (epitomized in the figures of Shiva and Dionysus). Our time is one of relativism and fragmentation, characterized mainly by a cult of death and a denial of roots and experiential sources other than those serving pragmatic and ideological interests. In view of this, does Daniélou’s book really deserve an attentive reading? Does it deserve a reading at all? Does it offer anything that may be deemed relevant for our present era? There is a difference between an “outdated” and (in the words “in-actual” book. The first is one belonging to the past with no message whatsoever for the present. The second is a book that goes against the (present) mainstream but has something important to say, a book compelled to wriggle its way through many different kinds of resistance in order to demonstrate its value. Alain Daniélou’s book belongs to the second category. It is an in-actual book with a considerable potential both for Indian and Western readership, because it faces the most important challenges of our time.

Daniélou affirms that “Dionysian” is the name of the Shaivite religion in the West, owing mainly to his conviction that pre-Christian cults and pre-Vedic religious forms share a common substratum.

In the first place, an archaeology of religious experience is not just an objective study of religious phenomena. In this book, Alain Daniélou not only delves into very interesting and relevant historical elements of both Indian and Western culture, but also conveys a message and a new world vision, advancing a singular elaboration of his own learning process in the context of Hindu Shaivism and its possible adaptation (and transformation) in the West, owing to correspondences in several ancient European cultural layers. His elaboration of Shaivism seems to go beyond its context of origin, but in fact (if we follow the main arguments) it recaptures the broad spectrum of what for Daniélou constitutes its archaic significance.

Shaivism, in the work of Alain Daniélou, is a very complex dispositive that differs considerably from any scholarly definition of it. We know that the textual sources of Shaivism can be traced back to epic poetry (especially Mahābhārata), with the fusion of the Rudra cult (of Vedic origin) and a figure of Shiva that blossomed later on in the Puranic literature (Śiva-,

Liṅga-, Skanda- and Kūrma Purāṇa, among others). Basing his hypothesis on iconographical material from Mohenjodaro, Daniélou traces the cult of Shiva back to the Indus Valley civilization, thus aligning himself with British archaeologist Sir John Marshall who, back in the 1930s, interpreted the famous Pasupati seal as a protoform of Shiva supported by features worthy of notice: the tricephalic character of the figure, bringing it close to mediaeval representations of the god; the yogilike posture, reminding us the Yogisvara aspect referred to in Skanda-Purāṇa; the head crowned with bull’s horns, opening a field of speculation on bull deities; and its ithyphallic character, relating to epithets of Shiva denoting overflowing – and erotically encoded – life-power (for example, when we consider epithets like ūrdhva-liṅ-ga and ūrdhva-retas relating to the thirteenth chapter of Mahābhārata). Such an archaeological hypothesis, which cannot be declared false, enabled Daniélou to conceive Shaivism not as a post- but as a pre-Vedic phenomenon.

Now, one of the main and most stimulating points of this book is the fact that Daniélou’s aim was not to discuss the archaeology of the Shiva cult, but rather to amplify its symbolic, religious and philosophical significance, the relevance of which not only concerns ancient Indian civilization but also contemporary issues both in India and Europe, such as the general social and identitary crisis, the disorientation of youth and the destruction of natural (and for Daniélou “sacred”) places through an increasing process of abstraction carried out by religious and political institutions. Daniélou’s thesis is that the religion of the Indus Valley (judging from its remaining fragments) was kept alive by the Dravidian layer of Hinduism that not only made its way into Puranic literature, Tantrism and part of the Bhakti cults, but also influenced the Brahmanic tradition, creating a fruitful tension with it. In other words: what Daniélou finds at the very origins of Indian civilization is not a mere archaeological object of study with no influence on the present, but a living religious and cultural complex permeating many aspects of the Hindu tradition and even overstepping the geographical limits of the Indian subcontinent, that is, something decisive in understanding the singularity of Hinduism and even the potential of some hidden, forgotten or repressed layers of religious experience in the Western tradition.

At first sight, the argument of the book seems to be the following: Shaivism, in the form that Daniélou attempts to reconstruct from the civilization of the Indus Valley to the theistic religious and philosophical system uninterruptedly transmitted through a succession of masters and disciples (sampradaya) down to our time, had a Western analogy in the Dionysian religion of ancient Greece. The main difference is the lack of continuity of transmission in the West, resulting in the disappearance of the Dionysian religion shortly after its expansion in late antiquity and its coexistence with other socalled “oriental cults” of the Roman empire (like those of Isis and Mithra). From this perspective, the comparison between the two gods (and therefore the intended parallel between the religions in question) remains asymmetric and somehow contradictory: what possible use is it to indicate a religion like the Dionysian mysteries if it is no longer alive? And even further: what is the purpose – if not a scholarly one – of comparing a dead religion (Dionysism in ancient Greece and Rome) with a living tradition (Shaivism in India)?

However, a closer look at the book reveals another type of argumentation. This is Daniélou’s thesis of proto-Shaivism (retraceable to Mohen-jo-daro) as a religious substratum surpassing the frontiers of India – as well as the specific period in which that form of pre-Vedic civilization is circumscribed – that provides the basis for a comparatist bridge. Daniélou sees in the prehistory of the Dionysian religion (that is, in Minoan Crete) the same scaffolding as in Mo-henjo-daro, and this is not a mere analogy. In fact, he affirms that “Dionysian” is the name of the Shaivite religion in the West, owing mainly to his conviction that pre-Christian cults and pre-Vedic religious forms share a common substratum. What does this substratum look like? Daniélou provides not only symbols (the bull, the serpent, the tiger, the phallus), but also very specific features of a religious world-view that enable him to link the Shaivite tradition with its strong continuity over millennia and the religion of Dionysus, which is apparently accessible only to researchers of Greek and Roman antiquity. The foundations of this worldview are the following: 1. A philosophy of divine immanence: there is no discontinuity of levels in the manifested world, that is, the mineral, vegetable, animal and human domain, as well as the subtle world of spirits and gods, exist through and for each other and make up the divine body. 2. A non-centralized philosophy of integration: every aspect of the universe can be used to achieve self-realization and reach the divine, that is, no species is privileged and therefore there is no need for separate levels including some aspects and excluding others.

3.A way of thinking distinguishing two sources of religion: the first and chosen one belonging to Nature (where each being plays its role in the divine game and maintains the harmony of the whole) and the second and rejected one belonging to city-life and cultural abstraction (where nature is destroyed, religious experience becomes moral rules and conventions have more value than intuition and inspiration).

It is easy to deduce, from the above-mentioned foundations, that (as Daniélou himself writes) “Shaivism is essentially a religion of Nature” (p. 15, English version), and that Dionysism is the Western variety of Shaivism mainly because Dionysos, like Shiva, is a transgressive god. In which sense transgressive? Mainly in the sense that he radically questions the social norms that conciliate the progressive alienation of human beings in the hands of institutional powers. This alienation consists of the structured belief (fed by a powerful ideology of the XX century leading to a radical change in the world-view of what is supposed to be the parameter of universality. European colonialism did not only bring destruction and exploitation, but also curiosity about the other and the need for a better understanding of it. Through ethnological works, the aware-ness of the “otherness” embodied in non-industrialized and non-alphabetic cultures has permeated the defence mechanisms aimed at perpetrating the cultural homogeneity of European expansion. The result has been a radical change in self-perception and a learning process that has only just begun, the main features of which are the relativisation of taken-for-granted conceptualisations such as the dichotomy nature-culture, revision of with manifold embodiments) that religion has to do with 1. recognition of an abstract prin-ciple detached from all possible levels of per-ception (empty metaphysics), 2. submission to life-denying moral principles (one-sided and even formal asceticism), 3. affirmation of an absolute truth to the detriment of all oth-er perspectives (religious fundamentalism). Daniélou’s critique also extends to secular fundamentalisms, whose political consequences are disastrous for the configuration of a “glob-al culture”.

One of the main aspects of Daniélou’s view on Shiva and Dionysos is his insistence that Nature is not only a quantifiable set of objects (trees, plants, animals, etc.), but a mystery-field full of divine forces.

Daniélou’s return to Nature is not illusory or naïve. On the contrary, it is a vision in tune with the most interesting contributions of human sciences today, especially those of eth-nology and anthropology in the last decades (negative) value judgements on tribal cultures and non-urban religions, critical reflection on the limitations of truth parameters related to modern science and an increasing sensitivity to the value of experiencing other paradigms from the inside. Today, it is evident that what Europeans called “universal” was, to some ex-tent, a projection of the very peculiarities they wished to expand. However, transcultural contact implies change, and this change is not one-sided. Today, after profound exploration of primal cultures outside the Indo-European axis, so-called “objectivity” towards Nature is largely proven to be a particular form of abstraction belonging to Western moderni-ty, and this abstraction, in spite of its cultural benefits, is – among other things – responsible for the ecological crises ravaging our so-called “global civilisation”. One of the main aspects of Daniélou’s view on Shiva and Dionysos is his insistence that Nature is not only a quantifiable set of objects (trees, plants, animals, etc.), but a mystery-field full of divine forces – forces that some human beings, such as Shamans or Vedic rishis or Tantrika, can understand and re-channel without damaging and destroying them. In short: his vision is not romanticism about Na-ture, but a realistic view of its complexity and the interdependence of that complexity with cultural forms that the dominant world-view of the West cannot control or even reach.

With the passage of time, and in view of the global situation today, it would not be an exaggeration to say that Alain Daniélou’s book, mainly written to show Western culture that the tradition of wisdom deemed lost since late antiquity can be found and even reactivated, is also important for post-modern India. There is always something very positive in change, because change is renewal, but in post-modern India, the young especially are becoming aloof and unaware of their own tradition, which begins, not with Gandhi and Nehru, but with the cluster of meanings around the Pasupati seal of Mohenjo-daro more than three millennia before Christ and continues through mani-fold ramifications, versions and subversions, commentary and critique, to end (or perhaps more optimistically: still goes on) with a pre-cious remainder of men of wisdom behind a massive proliferation of charlatans trying to quantify spiritual knowledge and experience by using the same logic as the global market, quantifying and reducing every manifestation of human agency to an emptied token of vir-tuality. The problem with modern India is not that it still copies the West – contributing in part to the perpetuation of a lower form of cul-tural colonialism – but that it copies the worst of it (massive industrialisation, uncontrolled consumerism, shallow imperatives of success and nihilistic fragmentation and dissolution of meaning), without realising that within their grasp are local treasures that may even have a reverse effect upon disoriented Westerners. With Gods of Love and Ecstasy, Daniélou shows that the triumph of life (to use the apotheotic expression of the poet Percy B. Shelley) be-comes visible in spirits that do not remain in the shadow of their own self-sufficiency and keep reintegrating knowledge and experience according to the parameters of new contexts.