Adrian Harris

Ecopsychologist, editor in chief of The European Journal of Ecopsychology

EMBODIED KNOWING, IMAGINATION AND NEW ANIMISM

In this essay, Adrian Harris proposes that the modernist worldview that we have inherited is deeply flawed, and that animism offers a more sustainable way of being for the present time, one which is deeply relational and embodied, one which engenders a deep respect for the other-than-human world. This embodied way of knowing is nurtured by relational imagination. The exploration of these ideas is carried out through the lens of contemporary Western animist spirituality.

Introduction

Until recently the narrative of the European Enlightenment has been a largely unchallenged story of how the world is. According to this story, only a mind can know, imagination is mere fantasy, and animism is a primitive error. But it’s increasingly apparent that in many ways this is a pernicious and false perspective: There are embodied ways of knowing, imagination underpins our understanding and animism may offer a more sustainable way of being. I’m going to narrate an alternative story that weaves together embodied knowing, imagination and animism revealing a tight synergistic pattern. It’s vital to tell this new story, because, as a well-known Native American proverb reminds us, “Those who tell the stories rule the world”.

For Francis Bacon imagination denotes “a world of fabricated reality, enchanted glasses, self-delusion, vanity and insanity”1. Although Sartre’s understanding is much more sophisticated, he still characterises imagination as “a negation of the real”2.

The term ‘Animism’ has a most inauspicious origin in late 19th century England. Edward Tylor invented the term to describe a ‘primitive’ type of religion, a childish and mistaken worldview that confused inanimate matter with living beings. By characterizing indigenous peoples as ‘primitive’, Tylor’s animism provided “an ideological supplement for the imperial project”3.

Western philosophy has marginalized the body since Plato. It suffers from what Elizabeth Grosz describes as “a profound somatophobia”4 and the notion of embodied knowing would have been unthinkable for Enlightenment scholars like Bacon and Descartes.

The dominant story in the world today is what we might usefully call Modernity; it is a story of disenchantment. In 1918 Max Weber characterized science as striving to describe the world through a “process of disenchantment”. In the disenchanted world of Modernity, “there are no mysterious incalculable forces” and there is no longer any need to “have recourse to magical means in order to master [it]”. Meaning and value must also be relinquished in such a scientific world-view: “the belief that there is such a thing as the ‘meaning’ of the universe” must inevitably “die out at its very roots”5.

A hundred years later, this powerful and deep-rooted story dominates our imagination, structuring what we perceive and believe. This story tells us how success is to be measured, defines what is of value and frames our relationships with others. But it engenders a sickness of the soul. As evolutionary psychologist Bruce Charlton writes: “It is learned objectivity that creates alienation – humans are no longer embedded in a world of social relations but become estranged, adrift in a world of indifferent things”6.

Maimonides was a medieval philosopher whose work has been described as a precursor of psychoanalysis. In a radical shift from the accepted notion that ignorance was the root of mental illness, Maimonides suggested that “Those whose souls are ill” suffer from a dysfunctional imagination7. The story of disenchantment is an expression of a dysfunctional imagination. It describes a dualistic universe without intrinsic meaning where the rational mind is the only source of understanding; where value is set by market forces and relationships are defined purely by exchange. It is increasingly clear that this story is unsustainable: As we will see, it is also profoundly mistaken.

Embodied knowing

I first became aware of the importance of embodied knowing through my spiritual practice. I realised that there is a deep “knowledge held within the tissue of our bodies”8. Delving deeper, I discovered many contemporary thinkers who had concluded that the mind is embodied and shaped by our experiences in the world9.

The map of embodied ways of knowing is complex but we can identify some primary features. Embodied – or tacit – knowing includes subjective insights, intuitions, hunches and the “bodily sensed knowledge” that Gendlin calls the “felt sense”10. Embodied knowing is largely non-verbal, pre-reflective and experiential, which led Polanyi to conclude that “we know more than we can tell”11. It’s a “knowledge in the hands”12 that’s situated and grounded in practical activity. This kind of knowing is familiar to indigenous peoples. For the Ojibwa “knowledge is grounded in experience, understood as a coupling of the movement of one’s awareness to the movement of aspects of the world “13. Embodied knowing is relational: We are not detached observers of an objective separate world, but active participants within it. As Bourdieu puts it, “[w]hat is ‘learned by the body’ is not something that one has, like knowledge that can be brandished, but something that one is”.14

Piles Copse, Dartmoor. Photo by Adrian Harris.

Piles Copse, Dartmoor. Photo by Adrian Harris.Embodied imagination

Embodied knowing is tightly enmeshed with imagination, and we would be unable to make sense of the world without imagery and metaphor.15 As the philosopher Peter Strawson notes, imagination is involved in activities ranging from a “scientist seeing a pattern in phenomena which has never been seen before … to Blake seeing eternity in a grain of sand and heaven in a wild flower”16. This is apparent in the work of Barbara McClintock, who won a Nobel Prize for her genetics research. Her insights emerged from a profound relationship with the plants she studied which was facilitated by embodied imagination. McClintock stressed the importance of having a “feeling for the organism” and opined that a scientist must “ensoul” whatever they were researching to reach a genuine understanding17. The plants that McClintock studied were not objects, but subjects.

McClintock explained her exceptional skill with a microscope in terms of her imaginative process: “when I look at a cell, I get down in that cell and look around”18 (Keller). This is a powerful example of what Merleau-Ponty calls “the imaginary texture of the real”19; the way in which imagination is at work in our perception of the everyday world. Imagination weaves together what is immediately presented to our sensory awareness and what lies just beyond it into the gestalt that is the world as experienced. This enables us “to shape the reality before us by regarding it and changing it in new ways, integrating possibilities with what is given”20.

The disenchanted model of reason presented by Weber seeks to exclude meaning and value. Such a model is a fantasy; we understand the world through imagination and make sense of it through stories.

Places like this ancient copse on Dartmoor create a sensorium soaked with unspoken meaning. Imagination draws me beyond raw sensory experience into the presence of other-than-human persons: Knowing that presence profoundly deepens my relationship with this precious patch of land. David Abram’s description of his fieldwork experience offers a good example of this process:

In the case of relationships, seeing makes it so: A relationship exists simply because we have identified it. When embodied imagination brings forth an awareness that we are in a relationship with other-than-human persons, relational animism naturally emerges. Crucially, this is a question of practice, not belief: The question of whether animism is empirically ‘true’ is irrelevant when we’re considering the relational dimension: Seeing a relationship with another being creates it.

Animism

Evolutionary psychologist Bruce Charlton suggests that animism is “spontaneous, the ‘natural’ way of thinking for humans”22. We are born animists, but that intuitive understanding is taken from us as soon as we learn to name it. Robin Wall Kimmerer fears that “the language of animacy teeters on extinction – not just for Native peoples, but for everyone. Our toddlers speak of plants and animals as if they were people, extending to them self and intention and compassion – until we teach them not to. We quickly retrain them and make them forget. When we tell them that the tree is not a who, but an it, we make that maple an object; we put a barrier between us, absolving ourselves of moral responsibility and opening the door to exploitation”23.

Despite the power of denial, a deep embodied knowing of the animate world remains. Under the right conditions that ancient knowing can sprout into life. Like a seed long buried in the dark that awakens to the touch of Spring, animism flowers with a little nurturing. Stephanie Gottlob – an improvisational movement artist – hadn’t ever heard of animism and though she loved nature she didn’t think of it as being filled with sentience. But that was before she took her work into the wild. Gottlob spent weeks living in some of the most remote parts of the world and when she began to dance in wild landscapes something unexpected happened: ”all of a sudden, that entity which is alive and active starts infiltrating into the improvisation“. Aspects of nature – perhaps a tree or a bird – improvise with her and this is an embodied process: “there’s nature in your body and the animism you might potentially feel is going to come through sort of a physical relationship with nature”24. The embodied relationality of animism that Gottlob highlights is fundamental and it reveals the deep flaw in Tylor’s conception of animism as an erroneous belief system. Tylor was looking at indigenous cultures through the distorting lens of Modernity, which is partly why scholars and practitioners increasingly talk about a ‘new animism’ which draws on recent ethnography and philosophy to reclaim the term. Tylor’s animism is based on a dualistic, hierarchical story about a world where there are entitled humans and the rest merely provide resources for our use. In contrast, the new animism “encourages humans to see the world as a diverse community of living persons worthy of particular kinds of respect,”25. New animism challenges the dualistic ontology of Modernity which divides the world into culture and nature, subject and object, animate and inanimate. It is “relational, embodied, eco-activist and often ‘naturalist’ rather than metaphysical”26.

Animism isn’t about what is believed but how the world is experienced. It’s “a condition of being alive to the world, characterized by a heightened sensitivity and responsiveness, in perception and action, to an environment that is always in flux”27. I suggest that it can best be understood as an embodied way of knowing that underpins how people live practically in the world; hunting, farming, navigating etc.

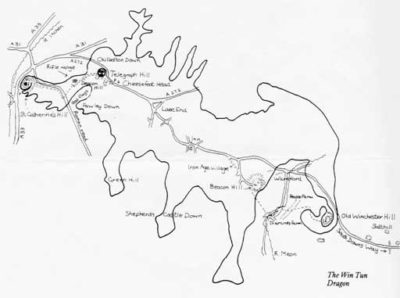

Animism is not only found in indigenous cultures; it is a living practice for some who live in contemporary Western societies. This is not another sad example of the Western appropriation of indigenous culture: Animism doesn’t need to be ‘imported’ or copied from elsewhere because it emerges quite spontaneously from the experience of living close to the land. My PhD research studied Eco-Paganism, a nature-based spirituality that has environmental activism as a foundational practice. This earth-based spirituality emerged from an eclectic mix of Wicca, environmental activism and ecofeminism, spiced up with the folk Romanticism of the free festival movement. British Eco-Paganism first flourished with the emergence of the ‘Donga Tribe’ at Twyford Down in 1991. The Tribe began when two young travellers set up a protest camp on the Down, which was threatened with destruction by a new motorway. Donga Tribe Eco-Paganism was earthy, characterized by spontaneous and unstructured rituals with a wild Dionysian edge. The Tribe had a strong connection to the genius loci and mythical stories were told of the ancient Earth energy of the Win Tun Dragon which lay slumbering in the landscape.

The Win Tun Dragon. Photo by Debbie Pardo.

The Win Tun Dragon. Photo by Debbie Pardo.Although I was involved with the Twyford Down protest, my research fieldwork began much later in 2005, when I joined fellow Eco-Pagans who were living in protest camps. These camps were often set up on land that was under threat from road building and some existed for years. Living on the land for weeks at a time can catalyse an animist spiritual connection and many UK Eco-Pagans developed a deep connection to the places they defended. For one activist it “was like being connected to a great river, the source of all life … and years of separation between us and the Land were falling away like an old skin”28. Tami and Ceilidh lived on the same woodland road protest site:

New animism challenges the dualistic ontology of Modernity, which divides the world into culture and nature, subject and object, animate and inanimate. It is relational, embodied, eco-activist and often ‘naturalist’ rather than metaphysical.

These contemporary animists developed a sacred relationship with the genius loci that was grounded in embodied knowing and imagination.

Communication with the genius loci is sometimes facilitated via an embodied felt sense. Zoe* describes her respectful approach to a sacred site:

An encounter with the genius loci can be life-changing. Before Lauren* started visiting protest sites she was “a very logical person” but one night she had a powerful experience “that really kicked me off with this whole spirituality Earth bit”.

Defending the trees: living close to the land on a road protest site in 2006. Photo by Adrian Harris.

Defending the trees: living close to the land on a road protest site in 2006. Photo by Adrian Harris.I was one of a small group of protestors living on a wooded parkland in Southern England. It was threatened by a road-building project and at the time of the events I’ll describe, we’d been living on the site for several months. We’d built tree houses, a communal cooking space and a compost toilet. Lauren was a retired schoolteacher who’d been drawn to the camp by her love of the place. Although Lauren respected the Eco-Pagan beliefs of many of those on the camp, she was resolutely secular. But one night, Lauren’s rational world-view was shaken to its roots. She’d enjoyed a relaxed evening chatting with some Eco-Pagan friends, and when everyone had gone to bed she wandered down to the compost toilet, which consisted of a toilet seat on a wooden box with a makeshift curtain around it. The toilet was at the far end of the camp, half hidden amongst a small grove of trees. I’ll let Lauren’s words tell you what happened next:

Lauren was very shaken and when she found that I was still awake, she asked me to come and see the “figure in the tree by the toilet”. We went back there together and she now saw the figure as not frightening but protective. She said she believed the Earth is drawing people to protect Herself. I laughed, as she said in the very same breath that she wasn’t spiritual!

Lauren saw the figure as a spiritual presence that was defending the land and who was bringing her a message. While it would have been upsetting if it had been a human leering at her, the fact that this was a spiritual encounter was much more disturbing. This experience inspired Lauren to become more engaged with nature-based spirituality and her sensitivity to the power of place became significantly heightened. When the protest ended, Lauren sold her house so that she could set up a woodland community.

Animism is common amongst Ecopagans and is also apparent in ecopsychology, notably in the work of David Abram and Theodore Roszak. Roszak, whose 1992 book was the first to use the term, writes that:

Ecopsychologist Andy Fisher provides an example of how a conversation with what he calls “nonhuman others” is facilitated through an embodied felt sense:

Fisher notes that “[t]he more I am able to attune myself to the natural world the more I discover that it is correspondingly attuned to me.”34

It is the affective and relational quality of imagination that facilitated Lauren’s meeting with the Green Man and that enabled Andy Fisher to hear Raven’s message. Jungian psychotherapist James Hillman opines that spirituality and imagination are synonymous: Spirituality offers us a particular perspective on the world and it is imagination that provides the metaphorical lens to shift our view.

Animism was framed as ‘a mistake’ by Tylor because he suffered from a dysfunctional imagination. Spending time living alongside the other-than-human world tends to nurture our imaginative perception and thereby our animist awareness. However, very few of us have the opportunity to spend months living in a less urban, ‘wilder’ place. Are there practices that might help us access the “innately animistic quality of experience” that Roszak identified as the goal of ecopsychology?

My PhD identified several practices that supported Eco-Pagans in their relationship with the other-than-human world. I call these the embodied pathways of connection. “There are many such pathways and I will only touch on two of them here. Perhaps the most obvious example is the power of nature connection and this has been my primary focus in the examples above. The felt sense is also significant for many, including Zoe and Fisher. The latter concludes that the felt sense is “the place where we discover the aims or intentions, the needs or claims, of the soul itself (the soul being the personification of the unconscious)”35.

Conclusion

Frater opines that “[t]he colonization of imagination is a collective cultural amnesia, one in which we have forgotten what we have forgotten, a loss of not just a theoretical understanding of animistic imagination but a whole way of being and acting in the world”36. His assertion hints at the deep parallels between Francis Bacon’s distrust of imagination and Tylor’s colonialist portrayal of animism as ‘primitive’. Both are mistaken and rooted in the same dualistic ideology. But whoever controls the story, controls the world: The story of disenchantment is one story, and animism is quite another. Both engage with the world as it is, emphasizing some aspects and concealing others. It is imagination that gives both stories life and there is a choice to be made about which we take as our own. The Native American novelist N. Scott Momaday avers that we need “to imagine who and what we are with respect to the earth and sky”37. Frater claims that “perceptions are not facts that point to material objects but malleable impressions, one of many ways in which we can imagine self and world”38. If that’s true – and all that I’ve said here suggests that it is – then we can truly re-enchant the world. We can intentionally shift our perception from the story of disenchantment of Cartesian Modernity to an animist story of community.

- Guido Giglioni: The Place of the Imagination in Bacon’s and Descartes’ Philosophical Systems, in: Élodie Cassan (ed.): Bacon et Descartes: Genèse de la modernité philosophique, Lyon: ENS Éditions, 2014.

- Kathleen Lennon: Unpacking ‘the Imaginary Texture of the Real’ with Kant, Sartre and Merleau-Ponty, in: Bulletin d’Analyse Phénoménologique [En ligne], Volume 13, Numéro 2, 2017: L’acte d’imagination: Approches phénoménologiques (Actes n°10). popups.uliege.be

- David Chidester: Animism, in: Bron Taylor, (ed.): The Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature. London, Thoemmes Continuum, 2005, p.80

- Elizabeth Grosz: Volatile Bodies. Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1994, p. 5.

- Max Weber: Science as Vocation, in: David Owen and Tracy Strong (eds). Trans. Rodney Livingstone:The Vocation Lectures, Indianapolis, Hackett. pp. 1 -31, here p.13.

- Bruce Charlton: Alienation, Neo-shamanism and Recovered Animism. hedweb.com

- David Bakan et alii: Maimonides’ Cure of Souls: Medieval Precursor of Psychoanalysis, Albany, SUNY Press, 2010, p.50.

- Adrian Harris: Sacred Ecology, in: Paganism Today Graham Harvey and Charlotte Hardman (eds.): Paganism Today, London, HarperCollins. 1996. pp. 149-156, here p.151.

- Lawrence Shapiro (ed.): The Routledge Handbook of Embodied Cognition, London, Routledge, 2014.

- Eugene Gendlin: Focusing. New York, Bantam, 1981, p. 25.

- Michael Polanyi, The Tacit Dimension, Doubleday, New York, 1966, p. 4.

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty: Phenomenology of Perception. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1962, p. 144.

- Tim Ingold: The Perception of the Environment. Oxon., Routledge, 2000, p. 11

- Pierre Bourdieu: The Logic of Practice, Cambridge, Polity Press, 1990, p. 73

- Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner, The Way We Think: Conceptual Blending and the Mind’s Hidden Complexities. New York, Basic Books, 2002.

- Peter Strawson: Imagination and Perception, in: P. Strawson, Freedom and Resentment, 1974, pp. 50–72, p.67

- Evelyn Fox Keller: A Feeling for the Organism: The Life and Work of Barbara McClintock . San Francisco, W. H. Freeman and Company, 1982. p. 198.

- Evelyn Fox Keller: A Feeling for the Organism: The Life and Work of Barbara McClintock . San Francisco, W. H. Freeman and Company, 1982. p. 69.

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty: Eye and Mind, In James M. Edie (ed.)The Primacy of Perception, Evanston, Northwestern University Press, 1964, pp. 159-190. p. 165.

- Jennifer Anna Gosetti-Ferencei: The Life of Imagination: Revealing and Making the World. New York City, Columbia University Press, 2018. p. 2.

- David Abram: The Spell of the Sensuous, New York, Pantheon Books, 1996, p. 20

- Bruce Charlton: Alienation,, Neo-shamanism and Recovered Animism. hedweb.com

- Robin Wall Kimmerer: Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. Minneapolis, Milkweed Editions, 2013.

- Stephanie Gottlob: Embodying Nature: A conversation with improvisational movement artist Stephanie Gottlob. buzzsprout.com

- Graham Harvey: ‘Animism – A Contemporary Perspective’, in Taylor, B., (editor-in-chief), The Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature, 1996, pp. 81-83, here p.83

- Graham Harvey (ed.): The Handbook of Contemporary Animism, Durham, Acumen, 2013, p. 2.

- Tim Ingold: Rethinking the animate, re-animating thought, Ethnos, 71:1, 9-20, here p. 10.

- Jim Hindle: Nine Miles. Two winters of anti-road protest. Phoenix Tree Books. 2006, p. 70-71

- Jim Hindle: Nine Miles. Two winters of anti-road protest. Phoenix Tree Books. 2006, p. 100

- Adrian Harris: The Wisdom of the Body: Embodied Knowing in Eco-Paganism, PhD Thesis, University of Southampton, 2008. p. 137

- Adrian Harris: The Wisdom of the Body: Embodied Knowing in Eco-Paganism, PhD Thesis, University of Southampton, 2008, p. 145

- Theodore Roszak: The Voice of the Earth. An Exploration of Ecopsychology. New York, Simon & Schuster, pp. 320 – 321.

- Andy Fisher: Radical Ecopsychology: Psychology in the Service of Life. Albany, SUNY, 2002, p. 102-103

- Andy Fisher: Radical Ecopsychology: Psychology in the Service of Life. Albany, SUNY, 2002, p. 103

- Andy Fisher: Radical Ecopsychology: Psychology in the Service of Life. Albany, SUNY, 2002, p. 228

- Alan Frater: Waking Dreams: Imagination in Psychotherapy and Everyday Life. Glasgow, TransPersonal Press, 2021.

- N. Scott Momaday: The Man Made of Words, in: Abraham Chapman, (ed.) Literature of the American Indians: Views and Interpretations New York, Meridian Books, 1975, pp. 96-110, p. 101.

- Alan Frater: Waking Dreams: Imagination in Psychotherapy and Everyday Life. Glasgow, TransPersonal Press, 2021.