Interview by Amanda Viana

ALAIN DANIÉLOU AND THE UNESCO COLLECTION OF TRADITIONAL MUSIC OF THE WORLD: AN INTERVIEW WITH JACQUES CLOAREC

In this essay, Aleksandra Wenta deals with early tantric magic and Alain Daniélou’s novella The Cattle of the Gods1, which forefronts the theme of local tradition centered on the worship of the Goddess in a small Himalayan village. The majority of the village population perceives this local cult as primitive, archaic, and dangerous. In certain sections of Daniélou’s novella, the reader is struck by the similarities of motifs, concepts and themes representing the local archaic tradition and topics related to current research on tantric magic. Aleksandra Wenta attempts to contextualize Daniélou’s within a broader theoretical and practical framework of early tantric magic.

Alain Daniélou in his office at the International Institute for Comparative Music Studies and Documentation (IICMSD) in Berlin, in the year 1966.

Alain Daniélou in his office at the International Institute for Comparative Music Studies and Documentation (IICMSD) in Berlin, in the year 1966.On the lowest shelves to the left side of the main bookcase of the Media Library at the Labyrinth, a country residence in the Italian township of Zagarolo, lies an almost invisible treasure: the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music of the World .2 Visitors could easily overlook this cultural treasure if they were not made aware of the lengthy series of LPs on the bookshelves. This collection is more than a historical or archeological finding and certainly more than a piece of ethnomusicological research work. It is an invitation to experience other worlds through a singular encounter with music in its manifold styles.

That Alain Daniélou was the protagonist of such a special encounter is not due to the fact that he was searching – after the fashion of colonial hunters – for a preconceived ‘thing’, but rather because he was able to experience both an aesthetic and an existential change within himself: he whirled from tonal and linear musical experience to modal and circular. He opened himself to the sacred rotation of other worlds.

In 1961 Daniélou was assigned a role – similar to that of a diplomatic agent – for the preservation of ancient musical traditions1. In this context, he created, in collaboration with UNESCO and the International Music Council (IMC; created by UNESCO in 1949) the world music record project UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music of the World . Within this project, more than one hundred volumes have been published by different labels and companies. Daniélou directed the series. He was in charge of recording, organizing and publishing the musical material until the end of the 1970s.

Jacques Cloarec, current president of the Alain Daniélou Foundation (FAD, ex FIND), was Daniélou’s main assistant. As such, he has also contributed to a musical project that has rendered the West much more sensitive to the value of other cultures. The following interview with Jacques Cloarec aims at rescuing memories of his participation in the project UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music of the World together with Alain Daniélou, as well as reflecting with him on questions concerning music, traditional knowledge, Western legitimation strategies and the scope of a cultural heritage with universal ambitions.

Amanda Viana: Alain Daniélou loved Indian music in its different expressions. He had a very special connection with it from the point of view of an ‘insider’, since he spent 20 years of his life in India learning the theory and practice of Indian Classical Music – not only its philosophy, theology and cosmology under the instruction of pandits, but also the sacred Rudra Vina with the master Shivendranath Basu.3 Through that learning process, he gained some very important insights and developed an interesting reflection on the psychophysical influence of music, leading to the publishing of some ground-breaking books and articles such as Sémantique musicale: essai de psychophysiologie auditive (Paris, 1967), Situation of Music and Musicians in Countries of the Orient (Firenze, 1971)4, Ragas of Northern Indian Music (New Delhi, 1980), Music and the Power of Sound: The Influence of Tuning and Interval on Consciousness (Rochester, Vermont, 1995)5 and Origines et pouvoirs de la musique (Paris, 2005). Indian music was the bridge to a much broader project: that of recording the music of different traditions throughout the whole world. In 1961, Daniélou’s musical path took a turn when he created (with UNESCO and the International Music Council) the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music of the World . You, Jacques Cloarec, entered Daniélou’s life one year later. You became his assistant, and therefore you were involved not only in the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music of the World project, but also in the tasks of the International Institute for Comparative Music Studies and Documentation (IICMSD) in West-Berlin between 1963 and 1979; and of the Intercultural Institute of Comparative Music Studies (IISMC) in Venice between 1969 and 1981. You also contributed to revitalizing, expanding, and safeguarding the traditional music of non-Western cultures. In The Way to the Labyrinth, Daniélou writes the following: “Jacques Cloarec, a wonderfully efficient young Breton who became my assistant in Berlin, took over all the technical aspects – selection, editing, texts, photographs, etc. – and made it possible for us to create a very large collection of records”6. Many questions follow from that engagement of yours: How was your first contact with Daniélou in the frame of UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music of the World project? How did you end up carrying out that task? What kind of instruction or preparatory training did you have for this? Did you get any ‘musical’ education from Daniélou himself?

Jacques Cloarec: In my teenage years, I was very interested in the popular music and dance of my homeland, Brittany. Since I hadn’t been raised as a catholic and therefore Christianity didn’t play any role in my early education, the question of religion was not present. The local folklore and the heritage of the Celts (as a pagan counterpart to Christianity in Europe) were things that began to interest me much later, in connection with Daniélou’s interests in that field. When I entered the Celtic Circle in the city where I lived, the reason was my fascination with Celtic and ballroom dancing, and of course music played a role in that experience. One could say that merely because of those early interests I already had a bridge to Daniélou. With regard to the UNESCO project, I must say that at the very beginning it was not easy for me to work with Daniélou. He had his own prerogatives, and I didn’t feel prepared for the musical aspect of the recordings. But this changed relatively soon: I listened to a lot of recordings, first of Indian music, afterwards of Chinese, Japanese and Iranian music. That was a kind of progressive music education at the side of Daniélou. Eastern music was different from what I knew of European classical music, and it struck me as very interesting. I realized that I could enjoy most of these non-European traditions, and that working with Daniélou would permit me to learn and experience more of that material.

Amanda Viana: In an interview with Peter Pannke, Daniélou declares the following: “It was only just after the war that the first tape recordings came out. Then I flew to New York and bought one of the first professional devices which was a Magnecorder, an enormous gadget, and with it I did many recordings… the French recording house published my first album of recordings from India, which had very good things already”.7 The first recordings of Daniélou became possible only after he had acquired the best magnetic tape recorder at that time, the Magnerecorder by Sonocraft and the first hand-crank Nagra (conceived by Stefan Kudelski). The first recordings of Daniélou took place in Benares and were published in 1954 by two prestigious American recording companies: Columbia (focused on popular music) and Folksways (centered on religious music); but his first anthological volume of classical music of India, Anthologie de la musique classique de l’Inde, was published in 1955 by the French recording company Ducretet-Thomson.8 Did Daniélou use this anthology as a guide, a kind of model for the later UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music of the World project?

Jacques Cloarec: The recordings at Ducretet-Thomson were a first publication with a pioneering significance. In a way it served as inspiration for the further development of Daniélou’s musicological project. The collections that followed the Ducretet-Thomson series were different, but the most important aspect of the whole story is that Daniélou had developed his own method and produced exceptional work before it all passed on to the UNESCO. When it did, that is, when the collections were published under the aegis of UNESCO, a note was printed in each of the volumes acknowledging Daniélou’s work: “Collected by Alain Daniélou and edited under the patronage of UNESCO and the International Music Council”.

Amanda Viana: The UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music of the World project is without any doubt a pioneering work in the history of ethnomusicology. In The Way to the Labyrinth, we read the following: “Jack Bornoff, executive secretary of the International Music Council, persuaded UNESCO to ask me to create a series of records on the great music of the Orient, then Africa, and hired me as an adviser for his organization. For the first time since its creation, UNESCO, (…) became involved in non-Western music …”.9 It was through British musicologist Jack Bornoff that Daniélou became acquainted with UNESCO10. Was it difficult for Daniélou to extend the horizon of UNESCO to the East?

Jacques Cloarec: Jack Bornoff worked as Executive Secretary of the International Music Council for quite some time. He was a friend of Alain Daniélou, and his interest in Eastern art and music was profound. In that sense, a door was opened for the work that was carried out later. For Daniélou, the problem was not that of including Eastern music in the UNESCO program – which, until that point, had focused on Western forms of art. The problem for him was rather to mix Western and Eastern music styles and to lose the specificity of each of them. By way of example: the American violinist Yehudi Menuhin was a close friend of Ravi Shankar and a member of the International Institute for Comparative Music Studies and Documentation (IICMSD) in Berlin12. Menuhin became acquainted with classical Indian music in the 1950s, and in the 1960s he published a record together with Ravi Shankar, West Meets East. Daniélou was not very happy with such experiments.

Alain Daniélou in his office at the International Institute for Comparative Music Studies and Documentation (IICMSD) in Berlin, in the year 1966.

Alain Daniélou in his office at the International Institute for Comparative Music Studies and Documentation (IICMSD) in Berlin, in the year 1966.Amanda Viana: What prizes were awarded to Daniélou in the context of the UNESCO project?

Jacques Cloarec: In the context of his musicological work, Daniélou received many awards, among others the UNESCO-CIM Prize for Music (1981), the UNESCO Kathmandu Medal (1987), and the Cervo Prize for new music (1991). He was also appointed officer of the Legion of Honour, the National Order of Merit, Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters (France) and Fellow of the National Indian Academy of Music and Dance.

Amanda Viana: In his interview with Peter Pannke, Daniélou says: “And then, after that, I was entrusted with that UNESCO project of records – which, after all, I did practically on my own, because UNESCO never gave me any money. But I thought that having the UNESCO label was very very important for the musicians, so, in fact, I gave it all to UNESCO, the collection to which they never contributed. And then, afterwards, it could only be developed when I obtained more funds with the Berlin institute”.11 It is surprising to learn that Daniélou didn’t receive any financial support from UNESCO, and that the further development of this project was financed by the International Institute for Comparative Music Studies and Documentation (IICMSD) in Berlin. Can you tell us about the formal framework of that project – for example staff, positions, editorial functions and further bureaucratic issues?

Jacques Cloarec: I don’t know much about the financial conditions and bureaucratic procedures concerning the first recordings. One can deduce at least part of that framework from what can be read in the cover of the volumes published by the UNESCO Collection: “Edited for the International Music Council by the International Institute for Comparative Music Studies and Documentation, General Editor ALAIN DANIÉLOU”. This means that Daniélou did the editorial work for an institution that served the purposes of UNESCO. The agreements were sometimes complicated because three different institutions were involved in the project (UNESCO, IMC13, IICMSD14). In addition to that, there was the editor, the musicians, or the owners of the recordings, which in some cases were other companies. I myself was also involved in the project on the level of translations, editing and other technical aspects carried out at the Institute in Berlin.

Amanda Viana: Could you tell us something about the International Music Council (IMC), created in 1949 by UNESCO itself? Did Daniélou or you take part in this council? Before choosing a music group or publishing an LP, was it necessary to have the authorization of this council?

Jacques Cloarec: Daniélou had absolute freedom of decision concerning the choice of musicians as well as of their cultural background. There was one exception, which is understandable given the historical and political situation of those countries: China and Tibet. When the Chinese National Commission for UNESCO (1979) was created, a volume on Tibetan Music had already been planned and was supposed to appear in the same year. The Chinese protested because, for them, Tibet was a Chinese Province and they wanted to put that on the cover of the LP. Of course, Daniélou did not agree with that point of view, and he ended up winning the debate using two very good arguments: the first one was that the idea of the collection did not concern ‘modern states’ but ‘traditional cultures’, that is, cultures outside the modern Western social structure and worldview. As we know, the Maoist Revolution was a product of Marxism, hence a product of modern Western culture. The second argument was geopolitical: the recordings on Tibetan Music were made in Dehradun, which is not Tibet but India. Now, the Tibetans living in India were political refugees, so writing ‘Chinese Province of Tibet’ would have been an insult for them.

Amanda Viana: The UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music of the World project implied working together with other companies, like Philips (Musical Sources), EMI/Odeon (Musical Atlas), Bärenreiter/Musicaphon (A Musical Anthology of the Orient, An Anthology of African Music and An Anthology of North Indian Classical Music), among others. How long did take for one LP record to get published? Did you take part in the editorial and publication process?

Jacques Cloarec: The relationship between Daniélou and the music companies was good in general terms, although I must say that, right at the beginning, we had problems in convincing Bärenreiter to take part in the project. The project was ambitious and therefore took a long time, I would say about five years. The plan was to issue two thousand copies of each title. I was permanently involved in the editorial process during that time.

Aanda Viana: After Daniélou’s death, recording companies like Auvidis/Naïve and Smithsonian Folkways followed the model he had created for their own research. Was that already stipulated in the contract between Daniélou and UNESCO?

Jacques Cloarec: I think they were compelled to follow Daniélou’s method, since it had already been established and for the sake of consistency it was convenient to do so. I don’t know whether that specific aspect was stipulated in the contract. One should perhaps consult the archive material to find out more about the formal aspects of the activities of recording companies after Daniélou’s decease.

Amanda Viana: The label created by Daniélou and UNESCO (with support from ICM) is called UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music of the World. This name triggers many questions related to the project: Was the decision about this label made by Daniélou himself? The concept of ‘traditional music’ is broad; it includes, for example, urban classical music and popular folk songs from rural areas. What do you think was the sense of that term for Daniélou? Can traditional music be labelled ‘religious’ or ‘sacred’ music? Is it related specifically or only tendentially to non-Western traditions?

Jacques Cloarec: Daniélou did not want the label ‘Traditional Music of the World’ to be officially related to himself, probably because the word ‘traditional’ in that context was too general and didn’t mean much to him. The project was therefore ascribed to the International Institute for Comparative Music Studies and Documentation (IICMSD), at least initially. This was for example the case of the recordings of Tibetan, Japanese and Tunisian music. We need to bear in mind that each series was a special task, as it is shown in the leaflets that accompany each volume, and that Daniélou was not happy with every LP in the series. For example, he didn’t want to promote the kind of music that is found in the series ‘Musical Atlas’ (he didn’t have much interest in that), and even if he enjoyed the music of the Ba-Benzele-Pygmees, he was reluctant to edit that material because of his own lack of expertise. A friend of mine, Michel Bonnet, became the director of EMI in Italy and agreed to publish that series.

Amanda Viana: According to Daniélou, ethnomusicology is in a way based on Western prejudices and its claims of scientific authority.15 But if Daniélou declines his role as an ethnomusicologist, how would you characterise his work on the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music of the World project? Was he really a kind of ‘ambassador’ of traditional (non-Western) music in the West?

Jacques Cloarec: At that time, ethnomusicology was mainly related to the idea of the primitive and exotic, considered to be in opposition to classical or sophisticated music. That is the reason why he avoided the term ethnomusicology and was even against its frequent use to describe projects concerning non-European music, since what he wanted to emphasize was the classical music of the East as an assemblage of very elaborate and complex music styles. Some of his texts clearly confirm that position, for example an article he wrote for an Italian dictionary of music. His idea was that the music styles recorded in the framework of the UNESCO Collection could easily equate the music of Mozart or Balakirev.

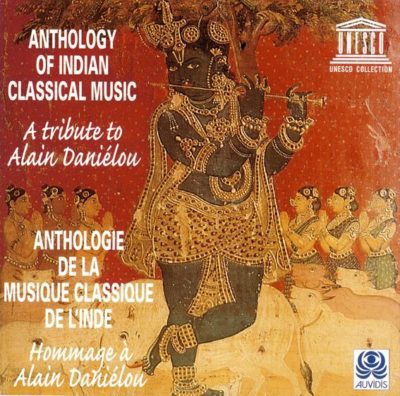

Anthology of Indian Classical Music. A tribute to Alain Daniélou LP album of UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music of the World.

Anthology of Indian Classical Music. A tribute to Alain Daniélou LP album of UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music of the World.Amanda Viana: We know that Western civilization has developed a high level of technical excellence in relation to audio-visual recordings. As such, different kinds of intangible cultural heritage could be collected by Westerners and ‘safeguarded’16. Beyond that, a special level of technical excellence could include the attempts of ‘quality improvements’ of musical works from other cultural settings. Do you think that Western technical excellence justifies the ‘necessity’ to safeguard the intangible contents of other cultures? What did Daniélou think about the attempts to improve the musical heritage of other cultures by means of technology coming from the modern West?

Jacques Cloarec: If we limited ourselves to technical excellence and its use to preserve the treasures of other cultures, I don’t see any problem. ‘Improving’ the musical heritage of other cultures is somewhat different, because it has to be carried out in the countries where those music styles flourish and according to traditional methods. When Daniélou came back to Europe, he was shocked by the ignorance of Western culture concerning the musical heritage of the East. I think that one of Daniélou’s major achievements was to provide the most refined music styles of Asia at a time in which the highest heading for them coming from a Western audience was probably ‘folk music’.

Amanda Viana: It seems difficult to transcribe the traditional music of other cultures into the system of the West, precisely because it belongs to other world-configurations and therefore requires another approach. Could you tell us about your experience with the recordings? How did you feel in dealing with them?

Jacques Cloarec: You mention an important point, since the question of the passage from one system to another was the reason why Daniélou didn’t like the expression ‘music of the world’. What he wanted to emphasize was the method, the discipline and the complexity inherent in each one of the cultural treasures he sought to make known or rescue from oblivion. This diversity cannot be mixed up and combined with Western variants, deformations or even different paradigms. For me it was a different experience with each of the traditions we dealt with: very enriching and instructive.

Amanda Viana: In a certain sense, Western civilization has a rather hypocritical role in the history of mankind: it has destroyed lots of tangible as well as intangible contents of other cultures and at the same time it attributes to itself the responsibility of safeguarding them.17 Do you think that the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music of the World project operated as a reservoir for local cultures? Was Daniélou aware of that role?

Jacques Cloarec: I think Western culture is not the only hypocritical form of culture in dealing with the patrimony of others, even if the colonialist project of the West was very specific and we still continue doing things related to that period. In any case, for me the UNESCO project was not a reservoir of local cultures. The idea was a kind of global patrimony of mankind. Daniélou, on the contrary, defended the particularity of each cultural group and the specific aspects of their tradition. He was convinced that if we pass from a local to a global project, such nuances inevitably get lost.

Amanda Viana: What was Daniélou’s first contact with the musicians he worked with? What kind of strategy did he apply to record their music? Did he offer money or any other benefit to traditional musicians? How was the recording process conceived? Was it spontaneous or planned beforehand? How were the research texts and images conceived for each album?

Jacques Cloarec: It is not easy to answer this question. Daniélou’s relationship with musicians depended on the kind of artist he met or worked with. Professional musicians with international experience were different from musicians within a religious group or popular musicians. But he was always very spontaneous in dealing with them. My task was taking pictures and looking for potential collaborators to establish contact with. I was also in charge of certain technical aspects like editing. As to the images and texts of each album, it was Daniélou who wrote most of the texts, but other people were involved, for example in the general production of the LPs.

Amanda Viana: Did any musical group require Daniélou to perform a special ritual to record them? Did Daniélou record any sacred song that is not allowed to be made public in any context than the original one?

Jacques Cloarec: As far as I know, he was never asked to perform any ritual as a condition to record the music. With sacred songs in India there is a very effective and relatively easy way of protecting them: it suffices to alter a couple of sentences or even words and the text no longer has to be preserved secretly. I supposed that was done in some cases.

Amanda Viana: What kind of audience was foreseen for the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music of the World project? Was Daniélou’s aim, apart from the preservation of the tradition, to divulgate the material among a wider public?

Jacques Cloarec: I think we can say that Daniélou’s purpose has always been to preserve the musical traditions still surviving in some non-European countries. In a certain way that has been done by the UNESCO project. The audience is of course a Western audience because it is they who should become more aware of the value of these other cultures.

Amanda Viana: Daniélou repeatedly said that listening to Indian Classical Music (which is not tonic but modal) requires, in the case of a Western audience, a re-education of one’s senses, emotions and way of thinking. In your opinion, how is this re-education possible? Did you experience such a thing as re-education of the senses?

Jacques Cloarec: Without a doubt one can speak of re-education. It is not about merely listening to music. If one really pays attention, one inevitably embarks on an aesthetic transformation, a transformation of the way in which music is perceived. I think that many Westerners today are capable of re-educating themselves in order to appreciate those music styles. That has been my own experience.

Amanda Viana: Is Western music (‘tonal music’) for you as annoying and boring as it seems to have been for Daniélou? Have you ever heard the whole UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music of the World project? How often do you hear extracts of it today?

Jacques Cloarec: No, Western music was not boring for Daniélou, who played Schubert on the piano and sang Fauré and Gounod; nor is it boring for me! Even if I do not listen to the radio and I barely watch TV, I think it good that France Culture or France Musique have programs in which our series are often played. That is also the case in Germany, and some of our ex-colleagues of the Institute in Berlin still play the music of the collection.

Amanda Viana: Which volume of the collection is the one you like best?

Jacques Cloarec: The volume on Dhrupad by the Dagar brothers – Mohinuddin and Aminudin Dagar – is the best music I have ever listened to in my whole life. •

- “Today, “music from far afield” has become a reference for many specialists and connoisseurs. These treasures have inspired many contemporary composers. We owe all this to Alain Daniélou. Today the existence all over the world, and especially in the Orient, of music, which is as classical as Bach and Mozart, is universally acknowledged: we owe that fact too to Alain Daniélou’s farsightedness and unstinting efforts.” Noriko Aikawa. “Anthology of Indian Classical Music: A tribute to Alain Daniélou”. In: Unesco Collection of Traditional Music of the World (1977). 3 compact discs, This collection received the “Diapason d’Or” award and, in March 1998, the “Grand Prix du Disque”. (CD). See: https://www.alaindanielou.org/discs/india-discs/anthology-of-indian-classical/.

- See UNESCO’s and the Alain Daniélou Foundation’s website concerning the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music of the World: https://ich.unesco.org/en/collection-of-traditional-music-00123 and https://www.alaindanielou.org/it/dischi/dischi-india/anthology-of-indian-classical/.

- Alain Daniélou. The Way to the Labyrinth. Memories of East and West. Translated by Marie-Clarie Cournand. New York: New Directions, 1987, p. 147.

- First edition in French: La musique et sa communication. Florence: Leo Olschki, 1971.

- First edition in French: Traité de musicologie comparée. Paris: Hermann, 1959.

- Alain Daniélou. The Way to the Labyrinth, 1987, p. 238.

- O.Ton 5: Interviewband Daniélou: Take 11: 1’50. In: Peter Pannke. “Alain Daniélous Weg ins Labyrinth. Zum Tode eines Pioniers der musikalischen Begegnung Asiens und Europas”. In: Eine Sendung von Peter Pannke. WDR 5/Redaktion Volksmusik. Sonntag, d. 10.09.1994 / 22.35 – 24.00. See also: Alain Daniélou. The Way to the Labyrinth, 1987, p. 237.

- Cf. Alain Daniélou. Fax direct to Le Monde. Service Culturel, Paris, 3 novembre 1992, p. 1 [Alain Daniélou Archive, Labyrinth, Zagarolo].

- Alain Daniélou. The Way to the Labyrinth, 1987, p. 237-238.

- Linda Cimardi. “One of the Richest and Most Refined Forms of Art in the World.” Alain Daniélou, the IICMSD Archive, and Indian Music. In: The World of Music (New Series). A Journal of the Department of Musicology of the Georg August University Göttingen [Postcolonial Sound Archives: Challenges and Potentials]. Vol. 10 (2021) 1 p.71-92, p. 85: “Indian music was certainly the main field of Daniélou’s expertise, acknowledged by his role as director of the College of Indian Music at the Hindu University of Benares (Vanarasi), as director of the Adyar Library of Sanskrit manuscripts and editions in Madras (Channai), and then as a member of the École Française d’Extrème-Orient in Paris.”

- O.Ton 5: Interviewband Daniélou: Take 11: 1’50. Peter Pannke. “Alain Daniélous Weg ins Labyrinth. Zum Tode eines Pioniers der musikalischen Begegnung Asiens und Europas”. In: Eine Sendung von Peter Pannke. WDR 5/Redaktion Volksmusik. Sonntag, d. 10.09.1994 / 22.35 – 24.00.

- Cimardi, 2021, p. 74: “The IICMSD was indeed funded not only by the city’s Senate, but also by the Ford Foundation (…)”.

- International Music Council.

- International Institute for Comparative Music Studies and Documentation (IICMSD).

- Cf. Alain Daniélou. La Civilisation des différences, Paris: Kailash, 2003, pp.148-149.

- Franzesco Pellizzi. “Chroniques : Ethnomusicologie et Radio-Télévision”. In: Diogène; Paris Vol. 0, ISS. 61, (Jan 1, 1968): 91-123, here 91 and 94.

- Franzesco Pellizzi. “Chroniques : Ethnomusicologie et Radio-Télévision”. In: Diogène; Paris Vol. 0, ISS. 61, (Jan 1, 1968): 91-123, here 92.